Born in 1899, James Smith McDonnell had attended college at Princeton and MIT and gained experience as an aeronautical engineer in the nascent American aviation industry with companies such as the Stout Metal Airplane Division of the Ford Motor Company, the Hamilton Metalplane Company, the Huff Daland Airplane Company, and the Glenn L. Martin Company. In 1938, McDonnell left Martin to establish his own company, the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation, which was opened on July 6, 1939, in St. Louis, Missouri. With the start of World War II in September of that year, McDonnell rapidly expanded its facilities and workforce as a subcontractor for more established design firms. In February 1940, the U.S. Army Air Corps began looking for a new interceptor design capable of reaching high speeds, having a long range, and be able to fly at high altitudes to destroy enemy bombers, with designers being encouraged to develop unorthodox aircraft with previously unheard-of performance statistics, with McDonnell hoping that the aircraft could reach up 472 mph.

Eager to prove their worth, McDonnell Aircraft drew up the design of they called the Model 1, which had a conventional mid-wing layout but with aerodynamic fillets on the wing root areas where the fuselage and the wings were coupled together. The initial Model 1 design was also unusual in that it was to have a single engine, such as the Allison V-3420 W-24 engine, buried in the center of the fuselage, with extension shafts and right-angle gears set to drive a pair of wing-mounted four bladed propellers in a pusher configuration. However, this design was revised to become the Model 2, which would be a more typical twin-engine tractor configuration design, while retaining the streamlined fillets, and being armed with nose-mounted guns. Further refinements led to the design being redesignated within the company as the Model 2A.

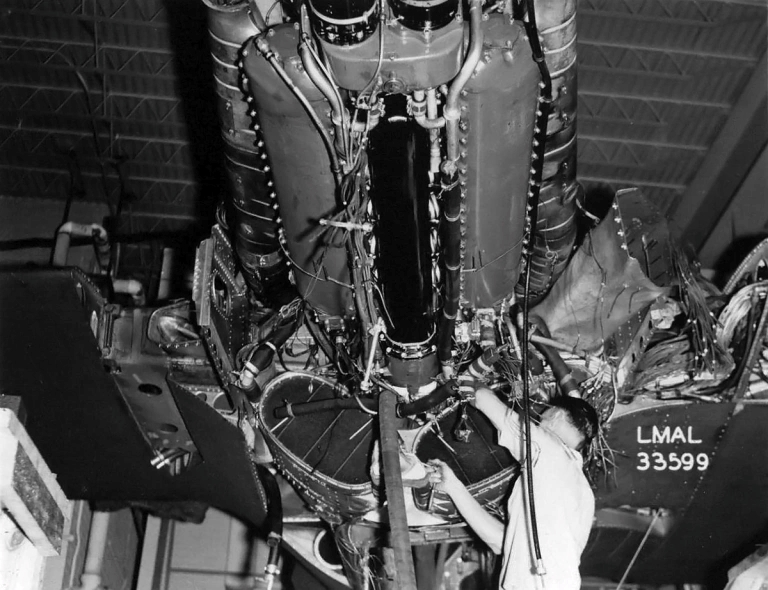

On September 30, 1941, the Army Air Force gave McDonnell the go-ahead with the design of the Model 2A as the XP-67 and ordered the construction of two prototypes for flight testing under the serial numbers 42-11677 and 42-11678, issuing a contract worth $1,508,596, plus an $86,315 fee for the program. The aircraft would be fitted with two Continental XI-1430 inverted V-12 engines that were expected to produce 1,350 hp. The engines were also coupled with the General Electric D-23 turbosupercharger to utilize the engine exhaust as additional thrust. The production model P-67 was also intended to be fitted with a pressurized cockpit, a novel concept for WWII fighters, and with an armament of six 37mm M4 cannons installed in the wings inboard of the engines, but these were not installed on the prototype.

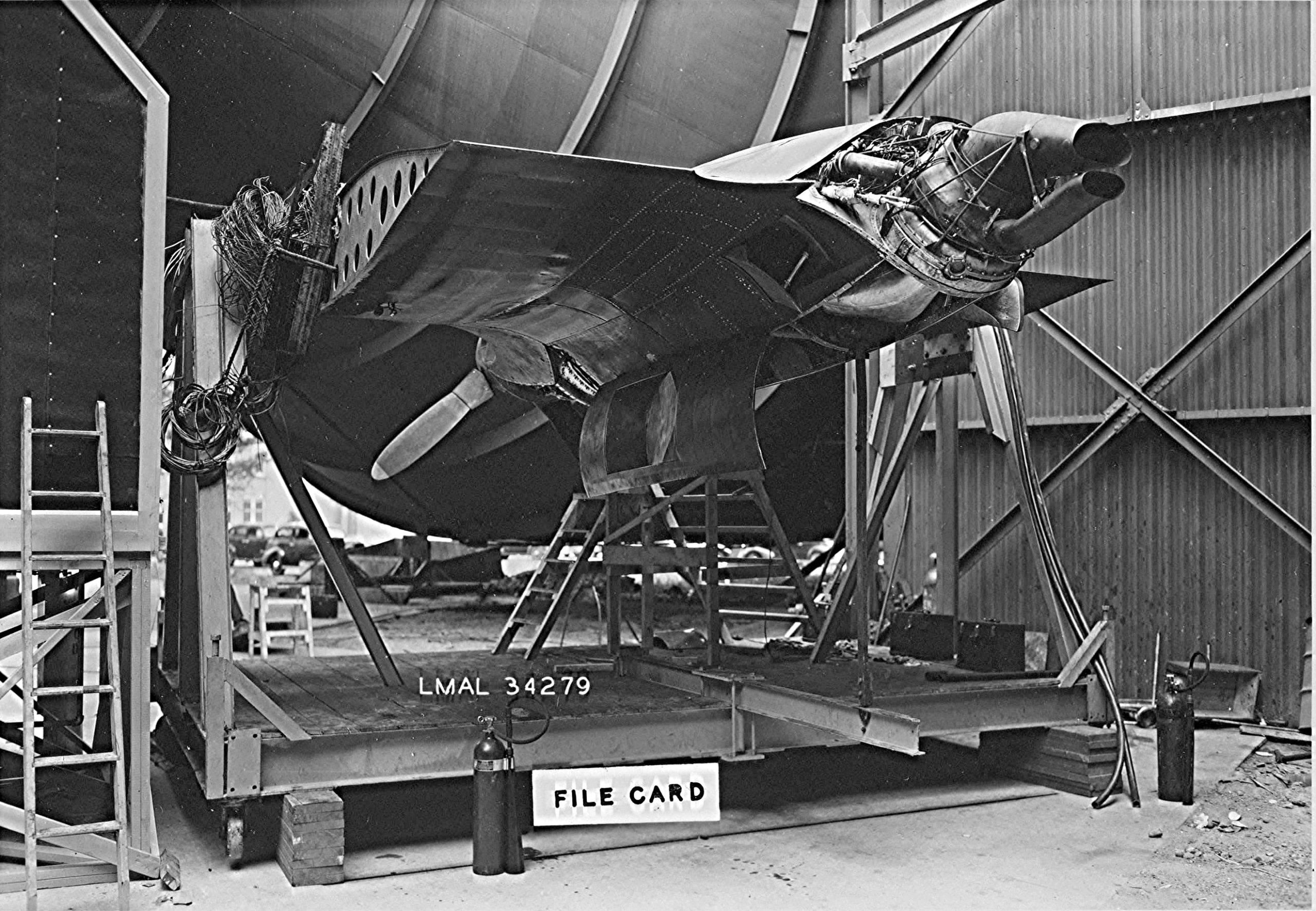

Development of the XP-67 was very challenging. Having never built an entire aircraft from the ground up, McDonnell Aircraft found it challenging to build an aircraft that required smooth surfaces that also needed to be precisely shaped. Also, the best place in the United States for full-scale wind tunnel testing of aircraft was at NACA’s Langley Research Center in Virginia, which was inundated with other, more established designers needing to test their own designs at Langley. But when the XP-67 models finally went into wind-tunnel testing, the design needed further refinements for optimal flying conditions. Worse yet, Continental was having trouble delivering a reasonable quantity of XI-1430 engines for the program, and the engine had been dropped from other aircraft designs already. With the XP-67 running behind schedule and overbudget, construction of the second prototype, 42-11678, was cancelled in October 1943, leaving just one example, 42-11677, to be finished by November 1943.

On December 1, 1943, the XP-67 was ready for engine testing and taxi runs. On December 8, however, fire broke out in both engine nacelles caused by a malfunction of the exhaust manifold slip rings that prompted repairs and further modifications. With these modifications finished, the XP-67 was brought to Scott Army Airfield, Illinois, just across the Mississippi River from St. Louis, where on January 6, 1944, test pilot Everett E. “Ed” Elliot took the “Moonbat” on its maiden flight but was forced to land after only six minutes due to overheating in the engines. After even more alterations to the nacelles, the aircraft was on its fourth flight on February 1 when the engines oversped and the crankcase bearings burned out. If that wasn’t enough, the canopy broke off, and once the Moonbat was back on the ground, it would undergo extensive modifications.

By this point, James McDonnell was frustrated with the engines of his fighter prototype. In addition to the constant mechanical problems, the Continental XI-1430’s power output was very underwhelming, producing only 1,060 hp compared to the promised 1,350 hp. He proposed new power plants for the “Bat”, such as the Allison V-1710 or the American development of the Rolls Royce Merlin, the Packard V-1650 Merlin, and even proposed making the XP-67 a mixed propulsion fighter with two General Electric J31 jet engines being fitted in place of the turbosuperchargers behind the Allisons or two Packard Merlins, but the Army Air Force insisted on reserving these for aircraft already in operational service until more testing was completed. For now, McDonnell had to make do with the Continentals. In the meantime, the Moonbat’s tailplanes were raised 12 inches based on feedback from further wing tunnel tests.

On 23 March 1944, flight trials resumed at Lambert Field in St. Louis. By May 11, Army Air Force pilots began evaluating the XP-67. Speaking of its positive qualities, they felt the cockpit layout was descent, its ground handling was good, the controls were light, the roll rate was adequate, and control and stability was generally effective. However, the overall performance was still underwhelming. Further modifications led to the gross weight increasing, bringing the design up to 25,400 pounds, the takeoff roll was exceedingly long, and the landing speed had gone from 76 mph to 93 mph. The aircraft also had a poor climb rate, slow acceleration, and the aircraft had a tendency to enter a Dutch roll, and during stall testing, the Moonbat buffeted above its stall speed, and the nose would tuck upwards during the stall. The pilot’s doubts over the XP-67’s recovery from a spin even led to the test pilots outright refusing to put it in a spin. In the end, it was deemed that the aircraft speed of 405 mph, nearly 70 mph slower than designed, and its maneuverability was inferior to existing designs already in service.

Upon returning to the flight apron from the McDonnell factory, the XP-67 gradually saw increasingly better performance, but was still chronically slower than other aircraft such as the P-51 Mustang and was still suffering from overheating and deficient power output. However, it was decided to complete the flight test program while the incomplete second prototype, which was still at the McDonnell plant in St. Louis, was kept reserve to be completed with perhaps an alternate engine arrangement.

On September 6, 1944, the XP-67 program came to an abrupt end when the starboard engine caught fire midflight. Test pilot E.E. Elliot was able to make an emergency landing at Lambert Field. Though he had sought to park the aircraft into the wind to blow out the flames, the right-hand landing gear brakes failed, and the fire blew towards the tail, burning the right wing, starboard engine nacelle, and the aft fuselage. Although Elliot escaped the fire unharmed, the XP-67 “Moonbat” was burned beyond repair and was subsequently written off.

With the second prototype only 15 percent complete, the XP-67 program was suspended on September 13 and was formally cancelled on October 24, 1944. The burned first prototype was later scrapped, and the second was never finished. The end of the XP-67 would also spell the end of the Continental XI-1430 engine’s development as well, for not only had upright V-12s like the Allison and the Merlin exceeded it, but soon, the arrival of the jet engine signaled the end of further development of twin piston engine fighters.

The McDonnell XP-67 may not have been the success that the young McDonnell Aircraft Corporation was hoping it would be, but its failure would not prevent McDonnell Aircraft from becoming a leading innovator in the field of military aviation and one of the largest employers in the St. Louis metropolitan area, right up to its merger with Douglas Aircraft in 1967 to become McDonnell Douglas, which would later be merged with Boeing in 1997. Yet even with its pitfalls, the McDonnell XP-67 has captured the hearts of many WWII aviation enthusiasts for its unusual looks. Perhaps with a better set of engines, things could have turned out differently, but that is for another discussion.

Today in Aviation History is a series highlighting the achievements, innovations, and milestones that have shaped the skies. All the previous anniversaries are available HERE