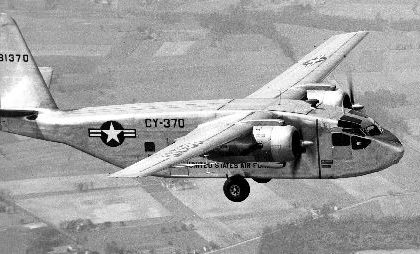

Recently WarbirdsNews presented a restoration report concerning the P-51C Mustang project underway for the Texas Flying Legends Museum, at AirCorps Aviation in Bemidji, Minnesota. While we had intended to follow this up with a piece on the razorback P-47D Thunderbolt they are also working on, we postponed that as we felt news of their Beechcraft AT-10 Wichita was of higher precedence. Yes indeed, while the Wichita is no looker, and doesn’t have the cachet of a combat aircraft, it served an important role in WWII preparing our pilots for advanced multi-engine types. In fact according to the National Museum of the US Air Force, “The AT-10 had superior performance among twin engine trainers of its type, and over half of the U.S. Army Air Force’s pilots received transitional training from single to multi-engine aircraft in them.” This is why we feel this project is so important… that coupled with the fact that only one complete survivor is currently known to exist (41-27193 at the National Museum of the US Air Force).

A significant reason for the lack of survivors is that despite the forward fuselage and engine nacelles being made of aluminum, the bulk of the aircraft… even the fuel tanks… was made of plywood. Plywood was a non-strategic material, which made the aircraft possible at a time when aluminum was in such demand for combat types, and its lightness contributed greatly to the AT-10’s superior performance. However, plywood doesn’t fare well for long periods outdoors, so the aircraft remaining at the end of WWII quickly succumbed to the elements. Barely a handful made it onto the civil registry.

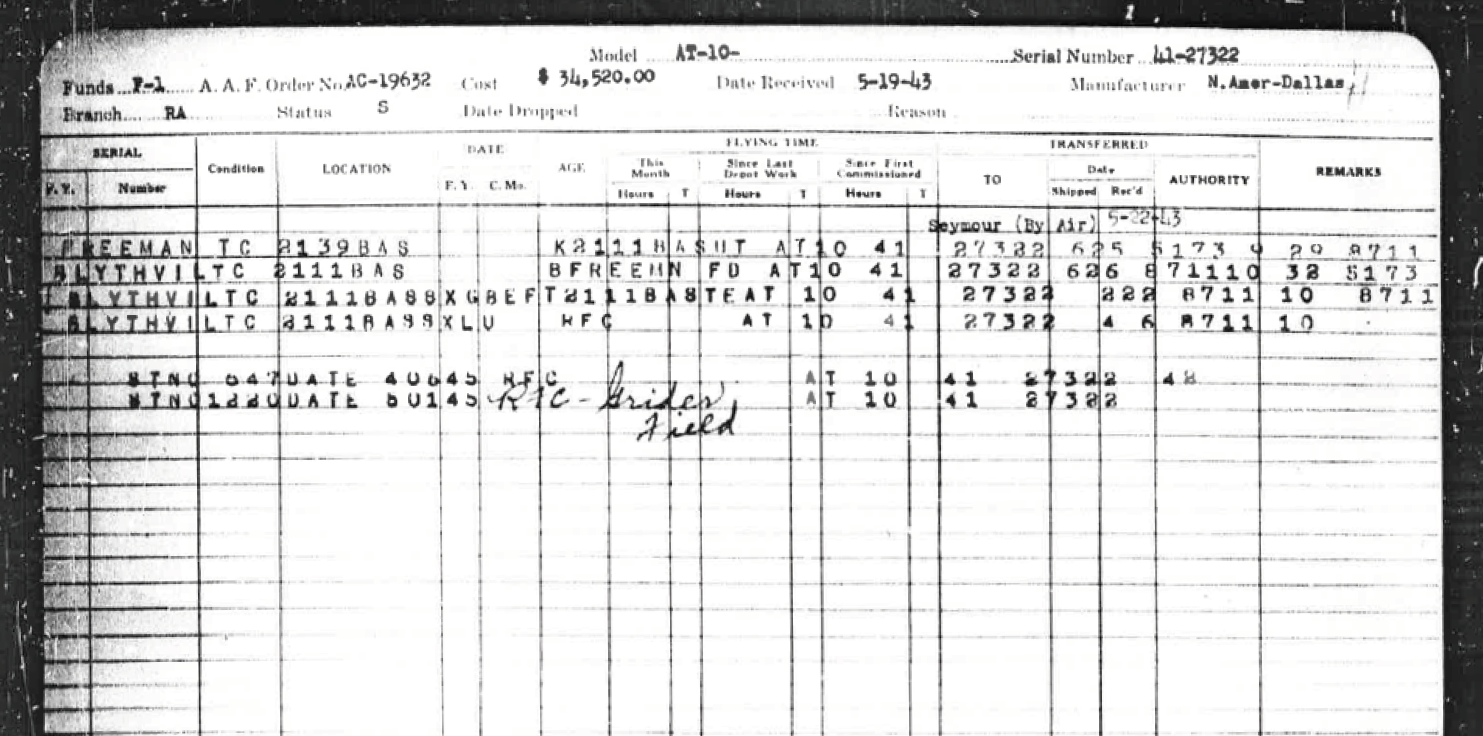

This project belongs to the Cadet Air Corps Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. The museum has collected the remains of several aircraft, but the restoration will focus on AT-10 41-27322. The components arrived at the museum last summer, and the restoration is already well under way. We will now let AirCorps Aviation’s Chuck Craven’s continue the story with his brief synopsis of the type, their aircraft’s history and an update on what the restoration team has accomplished so far.

The AT-10 at AirCorps Aviation

by Chuck Cravens

The Beech Model 25 project was designed to provide the Army Air Force with a small, twin-engine trainer suitable for developing pilot skills in retractable landing gear twins. It was to be produced with primarily wood construction, because there was fear that aluminum suitable for airframes would become scarce as the war progressed. The original model 25 prototype crashed on May 5th, 1941. Despite the accident, the design was promising, so Beech went ahead with further design development. Work on the trainer, now designated Model 26, began the next day.

Deliveries began in February 1942 and ended in 1943 after Beech completed 1,771 examples. Globe Aircraft produced another 600 in 1944. The Wichita, as it was named, was an important step in the development of twin engine fighter and two and four engined bomber crews, acting as an intermediate airplane between light, single-engine trainers and the heavy, high performance twins.

Most likely it was completed on that date or a day or two before. On 5-22-43, she was flown to Freeman Army Airfield, Seymour, Indiana and then on to Blytheville, Arkansas, on 6-24-43, arriving the next day. There she served until she was declared surplus on 4-6-45.

Her construction contract, AC 19632, was approved on June 5th, 1941 for a run of 1080 AT-10s, serial numbers 41-26252 through 41-27331. Contract AC 19632 was the third and largest production run of AT-10s. This Wichita was plane 1071 of this batch and the 1420th AT-10 built, including all separate production runs. She was built in the Beech factory in Wichita, Kansas, as were all but the last 600 of the 2371 AT-10s built. That last run of 600 were were the ones constructed by the Globe Aircraft Company in Fort Worth, Texas.

Possible WASP Connection

There were ten Women Airforce Service Pilots assigned to Blytheville, either from other bases, or after training was completed at Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas. The official archive of the WASP is located at the library of Texas Woman’s University and the figures shown in this report come from there.

Most of this group of WASP flew as B-25 co-pilots and AT-10 pilots, but WASP flew over 70 types of aircraft during WWII. Assignments included engineering test pilots, instrument check pilots, ferrying, and flight checks for returning overseas pilots. Thirty-eight Women Airforce Service Pilots gave their lives flying for their country. The following pages have information obtained from the pilot cards of the ten Women Army Service Pilots who may have flown our AT-10 at Blytheville Army Airfield, generously made available to me by Texas Woman’s University, the nation’s largest university primarily for women.

TWU is home to the national archives of the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). Please do not use images contained in this update without obtaining proper permission from the official archive of the Women Airforce Service Pilots at Texas Woman’s University. Continued research into a WASP or other pilot connection with 41-27322 will be conducted with a goal of locating a logbook entry showing that a specific pilot, male or female flew this airplane during World War II.

The AT-10 Arrives

On August 8th, 2016, Cadet Air Corps Museum AT-10 Project board members Sam Graves and Brooks Hurst arrived at the AirCorps Aviation hangar at Bemidji Regional Airport bearing “gifts”. The gifts were, of course, the components saved for many years to eventually use as the backbone in a restoration and rebuilding effort to once again put an AT-10 in the air. There are no flying AT-10s and only one complete example in existence at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, shown earlier.

Restoration Begins

Many thanks to Chuck Cravens and AirCorps Aviation for this article on their AT-10 project. Should anyone wish to contribute to the Cadet Air Corps Museum’s efforts, please contact board members Brooks Hurst at 816 244 6927, email at [email protected] or Todd Graves, [email protected]. Contributions are tax deductible.