By Ronan Thomas

Standing majestically in Bedfordshire farmland, their sheer size and engineering are testament to a previous age of confidence. At Cardington, three miles southeast of Bedford and fifty miles north of London, two vast green hangars crouch like latter-day Ziggurats. Visible for miles, they command the local countryside. These imposing Bedfordshire sentinels exert a magnetic pull on all who pass them by. In the 1920s the dream of British airship supremacy briefly flourished here. In 1924 the British government gave the green light for a new airship investment programme. Within five years, two state of the art, cigar-shaped silver airships roosted in the Cardington sheds’ enormous interiors, floated out to an awestruck public. But their potential was never realised, cut short abruptly by disaster.

Sentinels of Memory

The Cardington sheds were built during the First World War (1914-1918) as a direct response to German Zeppelin airship raids. Pioneered from 1900 by the Zeppelin Company, German military airships bombed the British mainland during 1915-1916, killing over 500 civilians and injuring around 2,000 others. The Zeppelin menace soon prompted a British strategic response. At Cardington, outside Bedford, a former Royal Flying Corps (RFC) airfield was repurposed as an airship works in 1916. Built by Shorts Brothers, it rapidly grew into a military and industrial hub – Shortstown – housing an 800 strong workforce. A huge airship shed (Hangar No 1) was built, housing the experimental hydrogen-filled airships R-31 and R-32 (R standing for ‘Rigid’). In 1917 an attractive administration block – the Shorts Building – was added.

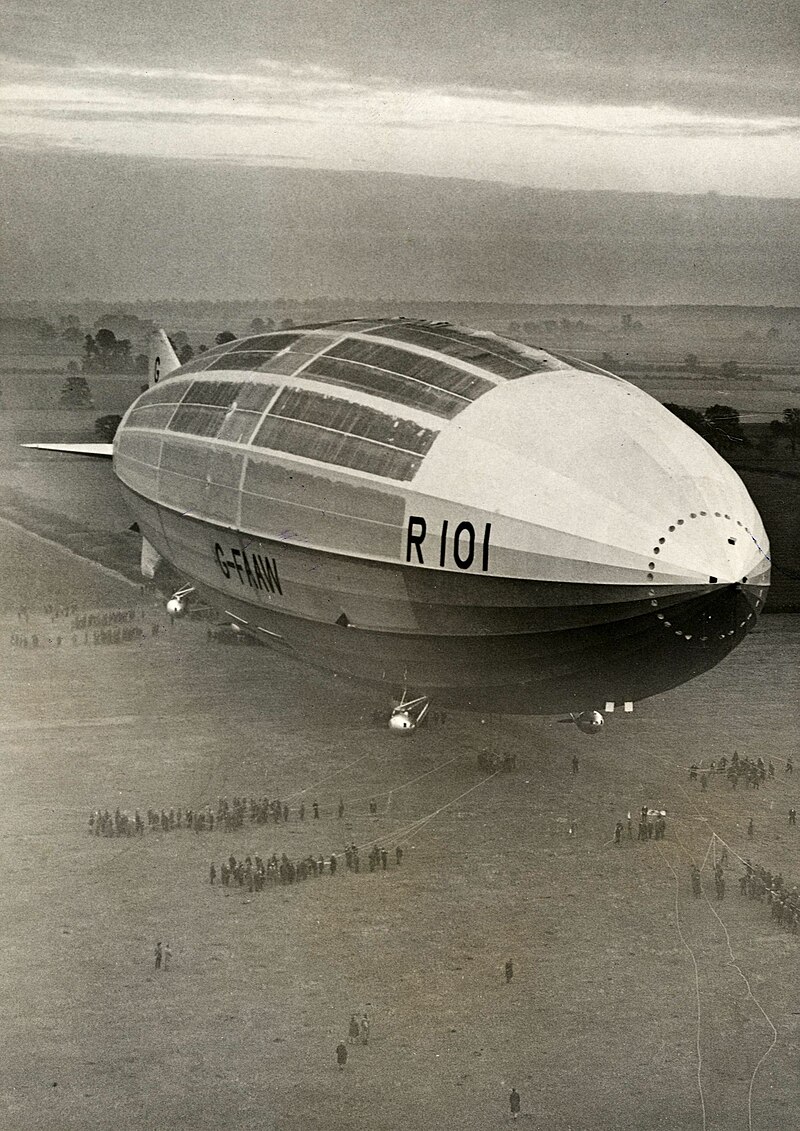

At war’s end the potential for British commercial airship development beckoned. The site was renamed the Royal Airship Works in 1919. In 1924 the British government launched an audacious ‘Imperial Airship Scheme’, investing £1.35 million to kickstart passenger and freight airship production. This innovative programme aimed to deliver a strategic airship network linking the entire British Empire and Commonwealth. It offered the promise of range, lift, freight, and passenger capacity beyond that possible using contemporary biplane aircraft. Cardington soon became the beating heart of operations. Two massive airships were built, the R-100 (at Howden, Yorkshire) and R-101 (at Cardington). Both airships were over 700 feet long and filled with around 5 million cubic feet of hydrogen. The R-100 was designed for the transatlantic route to Canada; the R-101 for the 5,400-mile route to Karachi in British India (today’s Pakistan). In 1926 a second huge hangar sprouted at Cardington. Hangar No 2, previously used by the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) in Norfolk, was assembled alongside its older sister. Both corrugated steel sheds were 812 feet long, 158 feet high and 180 feet wide. Each was longer than the Cunard liner RMS Mauretania. Their motorised electric steel doors alone weighed 470 tons. R-100 occupied Hangar No 2, the R-101, Hangar No 1. It was a tight fit. The sheds offered only 25 feet clearance for each airship leaving through the doors. A 200-foot-high mooring mast with an internal elevator was placed on the former RFC airfield, from which crew and passengers entered the floating airships. Both airships operated a crew of 42 and were designed to carry 50 passengers. Each airship had a large internal lounge and dining room, with available space for a band and dancing. Passengers sat in wicker chairs or perched on green cushioned wall-mounted benches. An angled glass-windowed promenade deck afforded them exceptional views. R-101 had a purpose-built smoking room. Completed in 1929, the R-100 and R-101 were icons of modernity, engineering marvels rivalled only by their sleek German counterpart, the Graf Zeppelin. The R-101, built at Cardington, was particularly feted. In 1929 London’s Times newspaper described it as “the biggest and longest airship in the world.” Powered by five 650-hp oil burning engines mounted in external cars, it was 777 feet long, its 15 gas bags filled with 4,893,720 tons of hydrogen. Both airships were to be the first of many, boosting Britain’s international trade as the nation recovered from war. Key government individuals – most notably the then Air Minister, Lord Thomson – obsessively championed their cause.

Confidence to Disaster

On 12 October 1929 the R-101 made its first test manoeuvres at Cardington, floating out from Hangar No 1 in front of a huge crowd of excited spectators. On 14 October it flew for the first time, to London and back. In nearby Bedford, people in the streets stared upward as the R-101 droned sedately 1,300 feet overhead. On 1 November it flew over Sandringham in Norfolk, witnessed by a young Princess Elizabeth (the future Queen Elizabeth II). On 16 December 1929, the R-100 made its own maiden flight and flew to Canada and back during July-August 1930. But Cardington’s promise was cut short, savagely. On 4 October 1930 the R-101 left Hangar No 1 on its first test flight to India. It crashed and exploded at 2am the following morning during a violent storm near Beauvais, Northern France. 48 passengers and crew were killed, including its champion Lord Thomson and Minister of Civil Aviation Sefton Brancker. There were six survivors (all crew members). The loss hit Cardington and Bedford hard. On 11 October 1930 a mass funeral of R-101’s victims took place at St Mary’s Church in Cardington, and a stone memorial was unveiled a year later. R-101’s damaged RAF ensign (flag) was retrieved from the wreckage. Mounted on a wall in St Mary’s, it remains today a poignant reminder of the disaster. R-101’s wrecked metal skeleton was salvaged from the Beauvais crash site, melted down and sold on to the Zeppelin Company. In the mid-1930s they used the metal in the construction of their own, equally ill-fated airship, the Hindenburg.

Airship and RAF Traces

The loss of the R-101 effectively ended hopes for a British commercial and military airship programme. The industry lay in ruins. In 1931 the R-100 was scrapped in Hangar No 1. But in 1936, as the threat of war in Europe loomed again, Cardington’s fortunes revived. The former airship works became a Royal Air Force (RAF) Station. Married quarters and other housing were built, and the site grew in complexity. The Shorts Building became an officers’ mess. The RAF converted the Cardington sheds to build thousands of barrage balloons, designed to deter low flying enemy aircraft. Run by RAF Balloon Command, they were inflated with hydrogen produced in its own on-site factory. Concrete pillboxes defended the airfield. After the war RAF Cardington continued as a gas cylinder filling and maintenance facility and (from 1953) a recruitment centre. From 1948 to 1963 the sheds and surrounding area became a National Service reception area, issuing uniforms and kit to young conscripts. The Parachute Regiment used balloons at Cardington for parachute training drops. The Royal Aircraft Establishment used both hangars for weather balloon testing, for building and fire testing until 2001. In 2000 RAF Cardington closed.

New airship research, testing and refurbishment has since taken place at Cardington (by Airship Industries, Hybrid Air Vehicles, and Goodyear). Meteorological research continues at the site. In 2015 the hangars were restored by English Heritage at the cost of £10.5 million. Hangar No 1 is now a Grade II listed building. Hangar No 2 is used as a film set by Cardington Studios, for Hollywood blockbusters including the Batman trilogy. Since 2012, new housing developments have transformed the local area. The former Shorts Building and RAF Officers’ Mess now offer private flats. Today, the towering Cardington hangars, from which the R-100 and ill-fated R-101 emerged, are the only such examples left in Britain. Close up they retain a spellbinding atmosphere. Apart from a guard at the film studios gate there are often few people around. Remains of wartime concrete defensive pill boxes on the former airfield are still visible. The large airship mooring mast was dismantled in 1943, but the imprint of its concrete base survives. On my visit, a Bedfordshire wind whispered around these twin, sunlit, ghostly sentinels, rich in Britain’s aviation history. A century after a British government invested in an elusive dream, the marvellous airship sheds at Cardington still haunt the imagination.