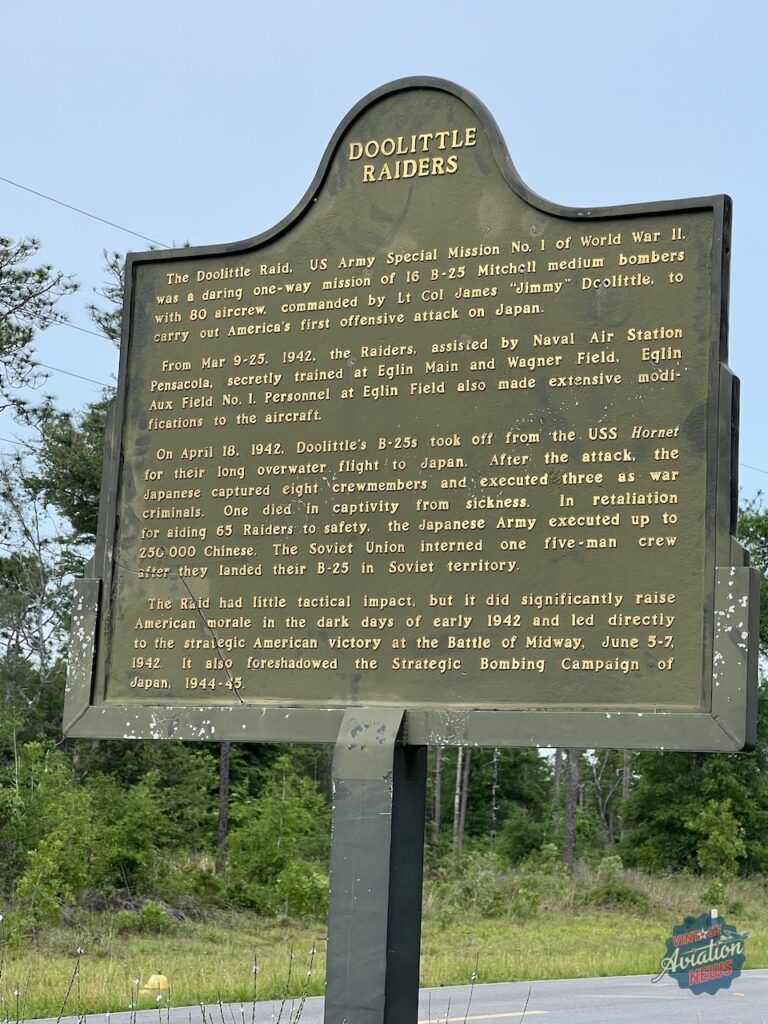

In the annals of military history, few acts of valor and audacity shine as brightly as the Doolittle Raid of April 18, 1942. This daring bombing mission, led by Lieutenant Colonel James “Jimmy” Doolittle, struck a resounding blow against Japan during World War II, boosting American morale and setting the stage for subsequent strategic operations. However, behind the legendary raid lies a lesser-known but crucial element: the rigorous training undertaken by the brave aviators, which took place at Eglin Airfield, Florida.

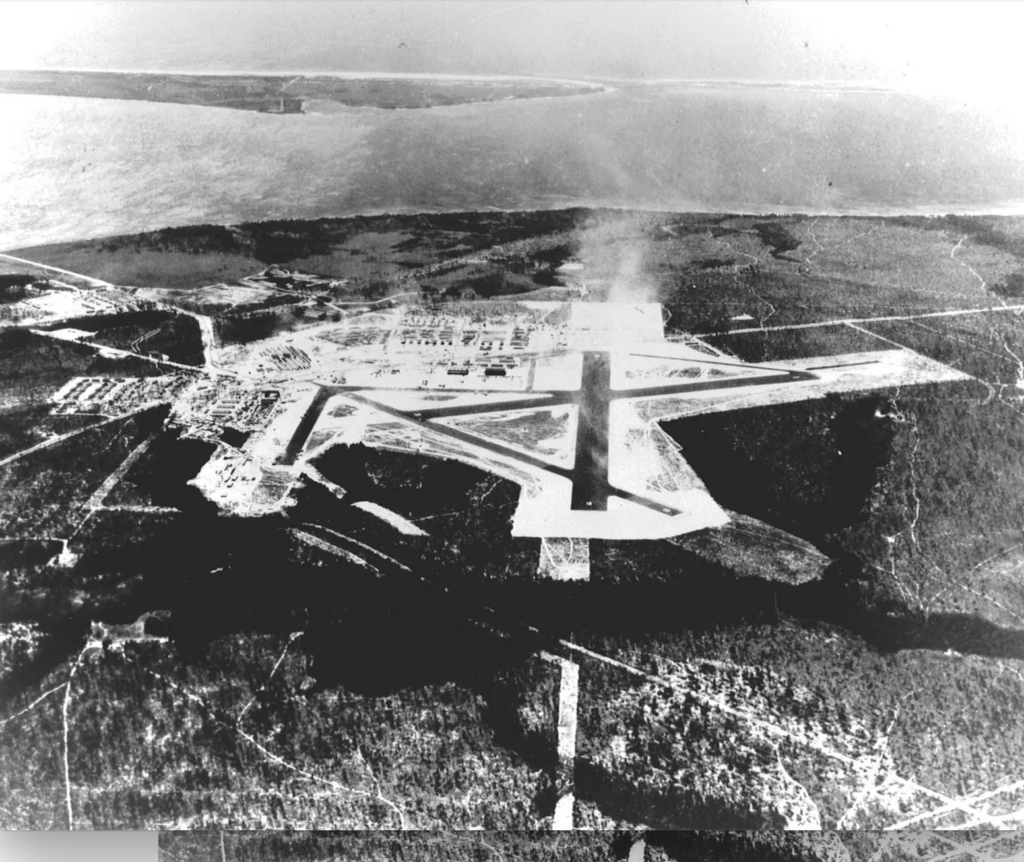

Eglin Airfield, nestled along the Gulf Coast, played a pivotal role in preparing the men and machines for the daring raid on Tokyo and other Japanese cities. Originally established in the 1930s as the Valparaiso Bombing and Gunnery Base, it quickly evolved into one of the most vital training centers for American pilots during World War II.

As the United States entered the war following the attack on Pearl Harbor, there was an urgent need to develop specialized tactics and techniques for unconventional warfare. It was in this context that Eglin Airfield became the training ground for what would become one of the most audacious missions in military history.

The Doolittle Raid, conceived in the wake of Pearl Harbor, aimed to strike a blow at the heart of the Japanese Empire, demonstrating America’s resolve and capability to retaliate against aggression. However, such a mission required meticulous planning and intensive training, both of which found a home at Eglin Airfield.

Robert B. Kane in a 2015 AIR FORCE Magazine article said that little definitive evidence exists, but it appears the raiders trained at Auxiliary Field 1 (later Wagner Field) and at Auxiliary Field 3 (later Duke Field). The 1944 Master Plan for Eglin Field specifically mentions Field 1 as a training field. History of the Amy Air Forces Proving Ground Command, Part 3, Gunnery Training 1935-1944, mentioned that the raiders trained at Field 3. Several raiders remembered training on a field north of Eglin toward Crestview—Field 3 is about 15 miles north of Eglin main, approximately halfway between Valparaiso and Crestview. On March 23, an aircraft flown by Lt. James Bates stalled, causing the aircraft to crash just after taking off from Field 3. The Raiders probably used other auxiliary fields to practice the short takeoffs.

Using photographs of the short takeoffs as evidence, some believe that the raiders trained at Field 4, Peel Field. However, those pictures are not originals from March 1942 but stills from the 1944 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer movie “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo” about the Doolittle Raid. The history of the AAF Proving Ground Command identifies Peel as Field 4 where the filming of the movie occurred.

Kane debunked a story told by a former Hurlburt Field base commander that in the 1950s may have started this story, and several official histories and raider interviews have perpetuated this belief. After Miller retired, he mentioned that the training occurred at “an airfield near the water,” possibly Santa Rosa Sound, just south of Field 9. However, the story is a total myth, as Field 9, much less a hard-surfaced runway there, did not exist in March 1942.

The Doolittle Raiders also practiced long-distance, low-level overwater navigation to enable them to fly long distances without visual or radio references or landmarks and to provide data for determining fuel consumption under actual flying conditions that the raiders expected during the actual mission. They flew from Eglin Field to Fort Myers, Fla.; then to Ellington Field, Texas; and after resting and refueling, back to Eglin Field. The first accident during the training occurred on March 10 at Ellington Field when the nose gear of Lt. Richard O. Joyce’s aircraft collapsed after landing.

In addition, the raiders conducted low-altitude bombing by dropping 100-pound practice bombs on Eglin’s bombing ranges and over the Gulf of Mexico from 1,500, 5,000, and 10,500 feet. They also buzzed some of the towns along the Florida Gulf Coast, producing complaints by local citizens to the Eglin base commander, Maj. George W. Mundy.

Under the leadership of Colonel Doolittle, a select group of volunteer pilots and crews underwent rigorous training at Eglin. The training regimen was grueling, pushing both men and machines to their limits. Flying B-25 Mitchell bombers, the raiders practiced low-altitude flying, navigation, and precision bombing – essential skills for a successful surprise attack against heavily defended targets.

Eglin’s vast expanse of airspace and range facilities provided the ideal environment for the raiders to hone their skills under realistic conditions. From low-level navigation flights over the Gulf of Mexico to simulated bombing runs against mock targets, every aspect of the mission was meticulously rehearsed until it became second nature to the crews.

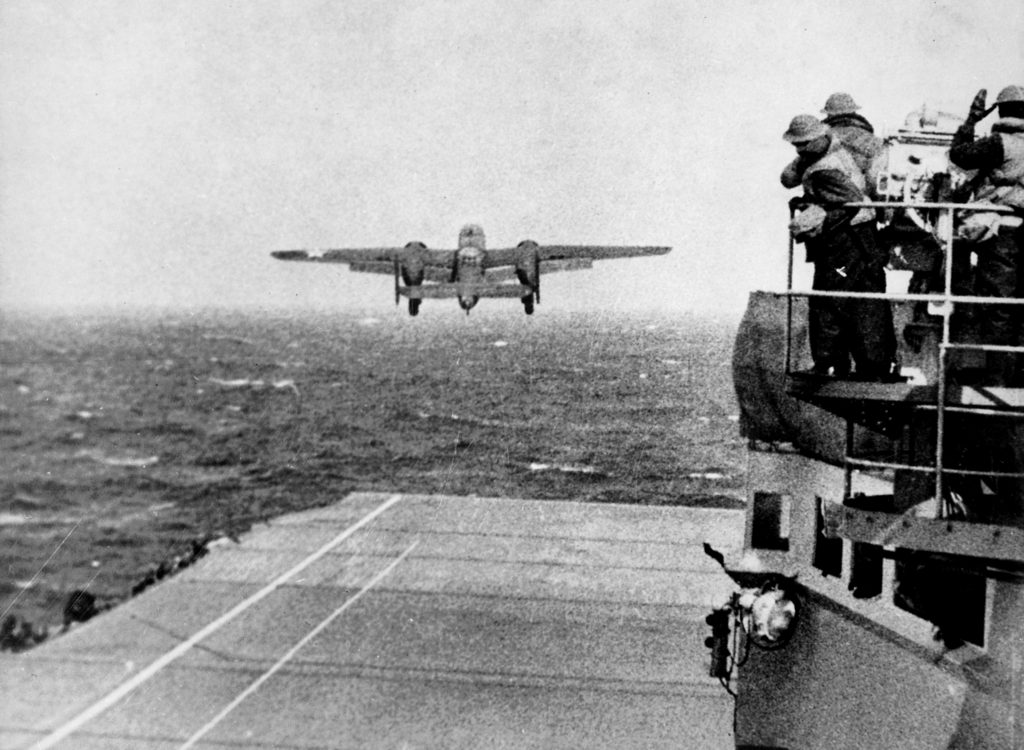

On April 18, 1942, the training and preparation at Eglin Airfield culminated in a historic moment as sixteen B-25 bombers, laden with fuel and bombs, launched from the deck of the USS Hornet and soared into the skies over the Pacific. Despite encountering unexpected challenges, including fuel shortages and the loss of several aircraft, the raiders pressed on, striking targets in Tokyo, Yokohama, Nagoya, and other cities before crash-landing or bailing out over China.

The Doolittle Raid achieved its strategic objectives, inflicting damage on Japanese military and industrial targets and lifting American spirits at a critical juncture in the war. Its success was a testament to the courage, skill, and determination of the men who trained tirelessly at Eglin Airfield, preparing themselves for a mission that would go down in history.

Today, these forgotten airfields stand as a living testament to the legacy of the Doolittle Raiders and their remarkable feat of heroism. History is all around you, you just have to look for it.

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.