Faced with wartime metal shortages, and a need to extend the range of fighter craft heading to Europe, the British came up with an ingenious design for auxiliary drop tanks, making them out of resorcinol glue-impregnated kraft paper, which while having excellent tolerance characteristics for extreme heat and cold necessary for operation on an aircraft as well as being waterproof, the glue would slowly dissolve from the solvent effects of the fuel contained within the tank, developing leaks within a few hours of being loaded with fuel, making them a strictly a one-time use item, filled right before takeoff.

The tanks were not considered robust enough to land a plane with them attached, so if a mission was scrubbed, pilots were required to drop their sometimes still-full tanks at a specified drop point, usually, the airfield’s dump where the tanks would be jettisoned, though surprisingly we could not locate any cases where this caused a conflagration.

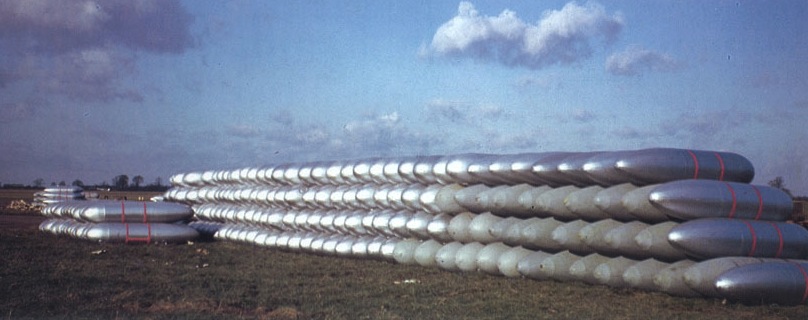

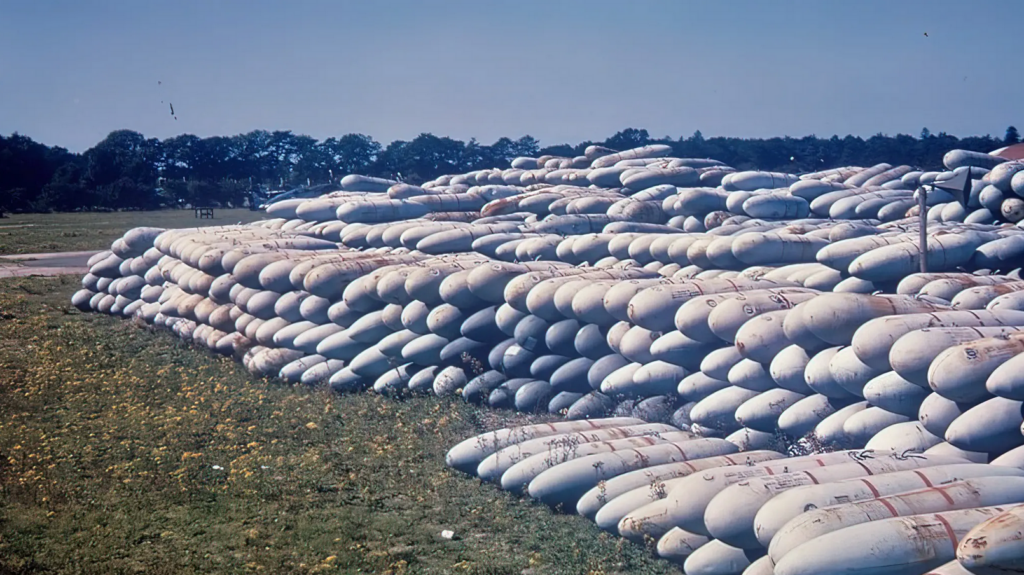

The tanks which were also sometimes referred to as “Papier-Mâché Tanks”, were assembled from three main components, the nose cone, tail cone, and the body. To ensure uniformity, the pieces were shaped over wooden forms. The center section was formed by wrapping layers of the impregnated paper around a cylinder to give the center portion its shape. The end caps were more complex due to their tapered shape and were hand-laminated with pieces of paper that were pre-cut like the petals of a flower. As each layer was applied with its glue, a special squeegee was used to ensure there were no wrinkles in the paper and no air bubbles were trapped. Wood baffles were installed within the cylinder and the pipes and fittings were attached, the tanks’ interiors were coated with a fuel-resistant lacquer and the three pieces were bonded together in a press. Once the tank had cured, it was pressure tested to 6 PSI, and passing tanks were given two coats of cellulose dope followed by two coats of aluminum paint.

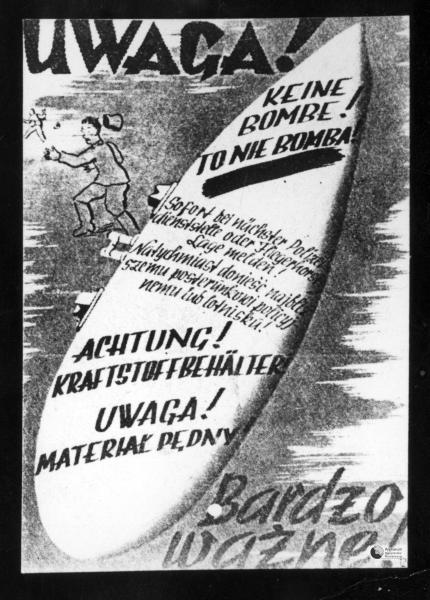

Other added benefits of the drop tanks’ paper construction were that the tanks themselves were lightweight and relatively easy for ground crews to handle, and when dropped en route to a target, were not supplying the enemy with scrap metal to feed their war machine. With the production of these tanks estimated to be over 13,000 over the course of the war, obviously, a lot of metal was saved. Very few of these tanks survive owing to their one-time use and little intrinsic value at the time, though they and other dropped tanks were a bit of a nuisance for those under the flight path when the tanks had served their purpose, with civilians mistaking them for bombs that hadn’t exploded, the Germans going so far as to distribute leaflets, explaining that drop tanks are not bombs.

A story we came across, about which we have our doubts, but will relate nonetheless, told by Charles D. Mohrle, who sadly passed away earlier this year, related the following: “One morning Sgt. Sing, our Squadron cook, asked me if I would help him with a project to which I agreed of course. He sawed a panel from the top of a paper gas tank in which we carried extra fuel – one that had not been used. He took the baffles out of the inside and hinged the panel he’d cut out so that it could be opened and closed. Into the tank he poured 50 gallons of powdered milk mix, ten gallons of mixed, canned fruit, ten pounds of sugar, some vanilla extract and a few other ingredients that I don’t remember. All this was mixed thoroughly and the tank was hung under the wing of my plane. Sgt. Sing told me to fly up to 30,000 feet where the temperature would be about 30 degrees below zero F. I was to slip and skid the airplane around for half an hour to keep the contents mixed up until it froze, then dive down and land as quickly as possible. When I parked the airplane Sgt. Sing dropped the tank off the wing and opened it up to reveal ICE CREAM. Everyone had a feast.”

Definitely sounds like one for the Mythbusters.

Neat! Now I want some drop tank gelato.

Does anyone know if the paper the Brits used for the paper drop tanks was ever made of hemp? I can’t recall my source any longer, but I heard the story years ago that drop tanks were often made of hemp saturated with a lacquer or shellac. I have not been able to substantiate it as fact however.

The U.S. paper tanks were developed by Col. Bob Shafer and Col. Cass Hough. Many hours were spent developing the tank and it was put in production at Bowater-Lloyds of London. Details and samples were sent to Wright Field for approval. Wright Field eventually replied that: Paper tanks are absolutely unfeasible and will not do the job for which intended” By the time that report arrived in England, the 8th Air Force fighters had discarded over 15.000 with a failure.

I’ve got one . Could be for sale

The British tanks were developed by my father in our house in Wembley. They were used by the Mosquito plane and many thousands were made after my father toured the country and taught people how to manufacture them in their kitchens, gardens, garages etc. They were practical and effective. They were all made of paper – no hemp involved.