Pilot Report: This another in our series of recorded flying experiences that we have received from readers and adapted for our website. We will publish further accounts from time-to-time, but are eager to record more for the future. If any readers are interested in sharing their own memories and stories with us, please do contact us HERE.

Recently, Frank Culemann treated us to a superb tale of his first experience flying an Italian Air Force F-104 Starfighter. This week we have a riveting account from Roberto Sardo recounting his terrifying moments nursing a crippled F-104 safely back to base. Sardo relates his story with such raw detail, that we are certain you will feel yourself flying alongside him as one emergency after another spikes adrenaline levels in the cockpit!

Supersonic Glider – Piloting the F-104 Starfighter In An Emergency!

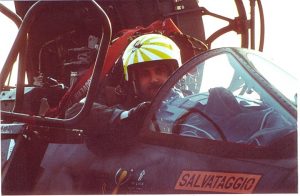

by Roberto Sardo

A supersonic glider…

There are airplanes that have a reputation for being “family fathers,” and then there are those that, for some reason, earn nicknames which bear absolutely no relationship to the real characteristics they possessed. For instance, some referred to the sleek and sexy F-104 as the Flying Coffin or Widow-maker. With her minuscule 6.6 meter (21’ 9”) wingspan and 17 meter (54’ 8”) length, she more resembles a missile than an aircraft. And yet – with her raised tail, pointed nose, perfectly faired canopy and diminutive air intakes, she has a captivating charm, the result of a wise and aggressive design…

During takeoff, the F-104 cannot fail to draw the attention, with her afterburner, a roaring 10 meter tongue of fire, echoing like thunder in a valley… Allowed to spring forth on this wave of power, with her sharp-edged wings, she easily penetrates the sound barrier at low altitude and doubly-so at high altitude. This plane has been a dream for several generations of pilots, and the object as much of veneration as bitter nostalgia, in those who left her. But her impact has also marked the grave for many of those who did not respect her fully, or had the misfortune of being in the wrong place at the wrong time…

I’m talking about a thoroughbred horse, the “one-o-four”, designed by a master who wrote the history of aviation: Clarence “Kelly” Johnson.

My tale is not about heroes, winged knights, or fighting aces. It describes one of the most frightening moments in my life, and perhaps one of the biggest risks I have taken as a pilot – a face-to-face adventure with an F-104 Starfighter. While she proved fatal to several very dear friends, I always considered the Starfighter a “family father” – demanding, uncompromising, strict, but always a family father…

That I can even tell this story is all due to the quality of my instructors at the Grosseto OCU, and MSG Cerboni. They created the most frightening situations for us in the simulator, repeating them over and over, until we learned how to solve them safely before actually taking to the skies. I owe a little of my survival to good luck, and a little to my personal way of doing things – sometimes a kind of “nonconformist” flying, always trying to predict intricate situations and studying them first on the ground with the manual, before testing them in flight.

It is March 1985. The flight starts with the usual planning. I am a Lieutenant Pilot of the 3rd All Weather Reconnaissance Fighter Wing of Villafranca (Verona, ITA). By now, I am in the advanced stages of training, and the targets to be reconnoitered with our cameras are hundreds of miles away from home. I’ve been tasked to spot and take pictures of a railway bridge and a road/rail crossing between Pescara and Vasto – way down south on the Adriatic coast.

Mission preparation includes reviewing the aircraft’s performance, fuel consumption, the mission route, the emergency altitude, the partial times for each leg of the journey and the estimated total flight time. Here comes the Intelligence Officer, tracing on my map the Order of Battle, the FEBA (Forward Edge of Battle Area), including “Triple A” (Anti Aircraft Artillery) and SAM site locations and ranges. I plan the direction of attack, the altitude on the ground, the type of cameras to use, the angle of the sun for the light, the start and end point of the film shooting, so as not to waste film or leave holes in the “swipe”…

All of these considerations I collected in the “navigation and target folder”, a condensed flight plan, which I will place on my kneepad. Before heading out to the aircraft, we study the latest weather situation – en route and over the target area – areas with no-fly zones (NOTAM) and escape routes in case of any adverse weather or airspace to avoid. Then comes the weather forecast (TAF) on RTB (Return to Base), the possible alternate airfields (Aviano, Istrana, Ghedi, Rimini etc.) and the relative minimum fuel for any such diversion (BINGO). Then comes a last check in the SOR (Squadron Operations Room) to see if the aircraft is ready, refueled and “pre-flight checked”, what her parking spot will be, and if the fuel/camera configurations meet what is needed. Then finally, checking the equipment, Life jacket, G suit and “leg straps”, signal flares, helmet, mask, gloves, kneepad, Folder, SSU-6 Cassette with memorized turning points, last weather reported at diversion bases and “BINGO”…

Everything is in place, and I have also managed to hitch a lift to the aircraft with the smoky “Campagnola” jeep, with a croaking gearbox, crushed under the weight of all the paraphernalia, with helmet, kneepad, anti-G suit hose, dinghy lanyard and maps hanging from all sides. When I arrive at the plane, after a quick glance to the aircraft “legs”, to assess the state of the shock absorbers and refueling, I’m greeted by the familiar dull and subdued roar of the idling ATLAS air compressor and the buzzing sound of the electrical power cart. Approaching, I can feel in my nostrils the typical “perfume” of the One-o-four, a mixture of JP4, hydraulic oil and something else I can never quite place.

Getting close to your aircraft is always a special ritual for pilots, a mixture of adrenaline, impatience, tension rising to its apex, reviewing in your head the torrent of numbers that summarize the entire mission … but above all, the adoring expectation for the miracle of flight that is about to commence …

As always, I put all of my stuff aboard in the order I will need it. I then check the maintenance log (Form-1), walk around the plane, to double-check every detail of the aircraft, sign the logbook and climb into the cockpit – leaping over the top of the ladder. Entering the 104 is quite easy, but settling in with full gear is a whole different thing…

Kneepad and maps fit under the windshield, waiting to find their place, while the helmet is resting over the windshield arch or in the makeshift bowl of the open canopy. Then, starting from the bottom, I begin to fasten the blue leg retraction straps, through the garters at the ankle and behind the knee… then the dinghy lanyard, the emergency radio, the ventral straps and the back straps. Now the crew chief adjusts the buckles, pulling the back of the bronze-colored belts, behind the shoulders. Next comes the helmet, its oxygen hose inserted into the cockpit connector and radio cable to snap in.

At this point the final details are arranged: kneepad, maps, flight data sheet… Gloves come last; they are normally placed under the windscreen, as they would hinder the grip on the connectors and toggle switches.

Ready to start the engine – right hand raised and swirling, with the rotating index finger pointing to the sky to indicate the engine spool up is about to begin. The Atlas compressor screams at full power, its gray and black corrugated tube swelling as if in a spasm. The starter switch is raised (N.1 or N.2, depending upon the day, odd or even), increasing revolutions in a crescendo of acoustic frequencies; 10% throttle “Idle”; jet temperature (EGT) within the limits; oil pressure increasing, …RPM 20, 30, 40%, stop Start – cut the air, RPM 67% stabilized, EGT <420°C…

At this point the dashboard comes alive; lights and warnings going off, indicators and needles begin to oscillate, monitoring the status of the various systems…

Immediately I switch ON the inertial platform, which requires about 7 minutes to align. In turn, the radio panels are switched ON, both UHF communication and navigation, and the radar knob goes on STBY (standby).

Then the sequence of cross-checks begins according to the conventional code of the “Five fingers”, a ‘dance’ of gestures between the pilot and two specialists on the ground; one in front and one behind the aircraft… One finger: Airbrakes, 2 fingers: Flight Controls (full deflection), 3: Trims, 4: Dampers, 5: APC (Attitude Control System), increasing values on the indicator until the intervention of the shaker (4,5 units) and kicker (5 units) on the stick, 6: (with closed fist) Exhaust Nozzle.

Pulling the red handle of the Emergency Control bypasses the normal control for the engine exhaust nozzle, the ‘turkey feathers normally operated by a hydraulic actuator using the engine lubrication oil, locking them mechanically. Control of the nozzle is very important, because their modulation always maintains an optimal ratio between gas pressure and turbine temperature – at all operating settings – from Idle to Full Afterburner. A failure in this system would result in almost total loss of thrust plus the ability to stay in the air…

Platform aligned and flashing, selector on “NAV”, radio call, canopy closed, yellow lever all forward, “Canopy Unsafe” Light off and……. READY TO ROLL!

A look around: The Crew Chief standing in front with arms raised – brakes off – ring finger on the steering button – engine up to the howling “Giant’s scream” and… the Zipper, loaded to her maximum weight of 27,000 pounds, with Tip and Pylon tanks, plus the 1,000 lb photographic pod in the centerline station, comes to life and moves on swinging. A decisive pressure on the rudder pedal and my loyal steed swerves ninety degrees towards the taxiway. A crisp salute with outstretched hand in front of the helmet for the ground crew, who respond – strutting – proud of their creature whose ready to take flight.

A quick radio contact with the Tower: the standard VFR departure “Clearance” is ready, “Borgoforte 1000″. I finish my sequence of checks like the aria “Ave Maria”: Tanks, WingFlaps, InertiaReels, SpeedBrakes, Spurs, SeatBelts, Canopy, Oxygen, Radios, Ejection Pins, AntiSkid, Defrost…

Before turning onto the runway, the weapons crew comes close for a last check of the safety pins. They give the thumbs up for the all clear! Radar-Altimeter ON – ready to line up – “Villa Tower, 103Alpha, Pins, Canopy, Swivel Guard (seat ejection lower handle safety), line up.”

One last quick check of the ejection seat safety – unlocked – and the canopy unsafe light.

On the runway, the adrenalin rises, a full pitch up-down excursion, to check the correct trim position, a quick glance at the white stripe on the stabilizer, through the mirror. “Stab” trim light Green (with the trim out of neutral, the rotation and lift off is not guaranteed…), push on the brakes, engine check.

Chronometer, throttle to “military”, check revving up time <10” and temperature peak. The fuselage vibrates, the RPM % passes quickly through 83% – the howl setting. The nose lowers under the angry thrust of the turbine as it reaches 100%. Slowly, back to 80%, then forward again: no “stalls”, 100%, EGT 690°, Nozzle between 1 and 3.5, Oil as per “placard”.

“Tower, 103 ready to take off.” The Tower authorizes. Lights on, pitot heater, chronometer, release the brakes, throttle over the side detent and full forward. First kick in the butt – the temperature has a splash, the nozzles open more than 7 – the second kick, nozzle at 9.5, a deafening rumble of thunder wraps the fuselage. The nose rises, the runway starts to flow past the cockpit, first it’s a lazy stroll, then gradually a canter and then a blur of speed… 100kts. Lift the finger from the steering button, fast comes the check panel, a white X on a black background. 135 knots, increasing with constant thrust.

I mentally repeat the Take Off/Abort procedure: Idle, Stores Jettison, Hook down, Drag Chute, Brakes… A fleeting glance at the engine instruments; nailed to maximum values. Now 150 knots, 180… everything is fleeing past and, as always in this heavy configuration, I start to see the end of runway lights rushing towards me; the “refusal” speed to abort take-off is already long gone – 200knots – 205 – I start to pull back on the stick. The nose rises, but the aircraft remains stuck down on the main wheels… 214knots – a slight pressure back on the stick again and the ground sinks beneath me. I see the airfield fence passing in a flash, my left thumb pushes forward the latch, while the other fingers wrap and pull up the landing gear lever, before the 260Kts, gear doors limit, the green lights out, handle red light off, the acute buzzing of the radar cooling fan ceases, I keep a flat climbing asset, it’s useless to force the nose up, at this stage. At full load, the ‘104 is like a steamroller thrown at full speed. You realize that you can’t stop her any more, nor can you force her to climb if she doesn’t want to. Steady acceleration, positive climb, outbound heading 245°, throttle back, behind the “detent” to “Military” power. 350 Knots, I slip two fingers under the plastic guard, small tilt back to release the lever safety detent and the flaps go up. Leveling off at 1000 feet, the Tower gives me the takeoff time and radio frequency change. 420Kts, Mach 0.64, about 7 miles per minute, I set the power to maintain speed.

Maintain Heading and flight time check; Channel 17 and I call the Departure. Meanwhile, here comes the Mincio river, Goito village, a left turn steering 165° towards the exit gate of Borgoforte bridges. I select the Pylon fuel transfer, and check that the indications confirm regular fuel flow to the fuselage tanks. The navigation proceeds at the standard altitude of 500’ without significant details, from one turning point to the next, radio call after radio call. Over the Check Points, I apply due course corrections and speed adjustments to keep the track and timing within limits without accumulating errors – This is full “oldtimer” VFR navigation, compass heading and timer! Before the Initial Point (IP) for the photo-run, the map indicates that I’m crossing the simulated FEBA. I accelerate to Mach 0.80 (540Kts) staying as low as 500’ and switch the cameras on, wait for the protective curtains to open (signaled by green lights). I shoot a test photo-burst; fuel is as planned, here is the IP – I adjust the position, dashing at 8 miles a minute, immediately steering to the attack heading and time check for the Target.

The ground is now rushing very fast underneath me; I maintain speed, heading, time counter… I look for details, comparing the map and the terrain, my eyes scanning ahead where I expect to see the target… There’s the railroad, over there is the bridge; I line up, my index finger on the trigger; shoot! I let go a burst of frames, then in a second, after crossing the bridge, I let go of the trigger. Evasive turn, simulating deception of the AAA gunners – low and fast as a dart!

Second target; same procedure. OK, I got it!

Now it’s time to bring the pictures back to the Photo Interpretation and Intelligence Officers. I reduce the power to get to Mach 0.64 (420Kts) cruising speed, heading north west; easy navigating along the coast. Engine dials – check – I’m computing the remaining fuel at the arrival. The tip tanks have finished their transfer too. I can move the fuel transfer switch to OFF. I notice I must have burned more than I expected; I reckon I can save a few hundred pounds of fuel if I gain some altitude. The fuel saved usually allows me to make a couple of GCA precision approaches, assisted by the precision radar or, better still, a “precautionary pattern with reduced power,” simulating a failure with the opening of the engine exhaust nozzle. The training program always requires the simulation of various potential failures – which I try to reproduce from non-standard positions – to evaluate and acquire, with the help of the Approach Radar, the flight characteristics of the aircraft.

I decide to climb up to 5,000 feet, notifying the Military Info Agency, and proceed homebound. I let the radar paint the coastline on the screen, re-checking the heading and flight time. Here I am over the Po Valley. In the backlight, the sun’s rays reflect off the mist creating an annoying halo which limits visibility to a few kilometers. I leave the city of Ferrara on my right, a little further to the north; Bondeno village should appear in a moment, with the geometry of its water channels. I feel like sneezing under the oxygen mask; a tingling in my nose, which in a moment becomes a burning feeling in my eyes. The air vents are pouring an increasing flow of smoky steam – that’s strange – this plane doesn’t usually make any condensation through the air conditioning system… A strange taste fills my mouth – greasy, bitter. I rub my eyes – they now feel itchy – while the condensation becomes a white stream invading the cockpit. My throat burns too – something is wrong – I start coughing… Oxygen 100%… I open the data folder; Emergencies check List (BOLD FACE) <FUMES or SMOKE in the CABIN: OXYGEN 100%, Emergency if required>

A stream of air pressure swells my mask and my lungs with the strange taste of pure oxygen. The steam continues – thick, dense, almost hiding the dashboard and the windscreen in front of me. A sensation of panic – a grip on my stomach – something is going wrong. I block the instinct to eject the canopy and get rid of the suffocating smoke! Yeah – Smoke in the Cabin – If it’s a short circuit, I have to cut the power off. I’m going to lose all electrical instruments. I call on the radio, “Padua Military, this is 103, Bondeno, 5000 feet. I’ve got problems. I’m heading for Villafranca. I’m going to lose my radio for a while.”

Control replies, “103 are you declaring an emergency…?”

“Affirmative.” >Check List< Cabin smoke; I suspect a short circuit. I need to disconnect the generators and electrical utilities. I lift the red guards on the right panel; GEN.1 <Off>, GEN.2<Off>. For a moment the emergency “CAUTION” and “Panic Panel” light up – then the whole instrument panel goes off.

I’m ALONE now. It all took less than a minute after the fumes began; smoke is still pouring in. I decide to open the Fresh Air Scoop – the forced ventilation knob – which cuts pressurization and air conditioning in the cabin. Suddenly the white stream stops, and the air that breaks in through the little side port clears the thick smoke a little. I look outside again, but against the reflection of the sun I can only see a gleaming mist. On the dead PHI (Position Homing Indicator), the needle is still pointing the last indications of the home TACAN as 290° and about 45 miles to run. My eyes are burning. I struggle to keep them open, but at least the smoke is gone and I’m breathing pure oxygen. I check again that all of the radios and electrical utilities are switched OFF. Then I decide to turn the generators back on, one at a time, checking the results. GEN.1 <ON>… Half of the failure panel lights up.. GEN.2 <ON>… All should go out – now – but the MASTER CAUTION remains on. The eyes run to the panic panel, and in fact a small light is still on… <ENGINE OIL LEVEL LOW>

For a short second, I’m a bit lost… What does the engine oil have to do with a short circuit; the systems are not related… In the blink of an eye, my gaze hits the engine oil pressure, which has collapsed to 2, then 1… “Madonna mia…!!!!!”

The RED NOZZLE lever… I grab and pull it all the way out, but nothing happens! With cruel slowness, the NOZZLE indicator moves opening at full scale, 8, 9… The oil level must have already dropped below the 4 pints mark; the emergency pump doesn’t get any more fluid, nor has the mechanical lock managed to block the engine exhaust iris… I look outside again… Where am I…? I turn the radio back on, IFF and TACAN. The airspeed’s quickly decreasing; with the wingtip, pylon tanks and the recce pod, I’ve got the maximum drag index. Even moving the throttle to 100%, I can’t feel any thrust.

<Emergency Check list! Oil system failure: 83-90% engine RPM to maintain maximum lubrication of the turbine bearings…> I remember in a flash the note in the Dash-1 manual: <with complete oil leakage, the J-79 engine can run for up to 2 minutes at 100% without permanent bearing damage. The engine can run for about 4 or 5 minutes at 90% before seizing. High engine settings and abrupt power changes should be avoided to keep the temperature and bearing loads to minimum. Increasing vibrations indicate impending bearing failure. Variations in throttle settings accelerate the failure>.

I have already lost about 2,000 feet and the speed has dropped to 350…

Position! The TACAN shows me Villafranca 20 degrees to the right, about 30 miles out. I’ll never make it home. I can’t abuse the engine either, or it’ll seize up! Meanwhile, I’ve switched to channel 17, with Garda Approach. I declare an emergency, then select “Emergency” on the IFF. I can hear the echo of my voice back in the headphones: the adrenaline gives me an almost baritonal note…

In a quick jumble of numbers, all of my exercises in “Partial Thrust Landing” come back to mind. Too bad that most of the time, in our simulations, we start from an optimal altitude and position… almost always. 30 miles to run, means 15,000 feet of altitude loss; then I will have to veer more than 90° to the right to intercept runway 05. That means another 4,000 feet lost; alignment with at least 1,000 feet residual…

I don’t think about it twice; I’m no longer able to keep a level flight. Speed is still decreasing, altitude decreasing… the plane is lost… Throttle full forward, “detent”, Afterburner… NOTHING happens! There isn’t enough pressure in the exhaust pipe for the ignition to happen. “To hell with it!” I throttle back, minimum sector afterburner, then quickly full forward again, FULL….. BOOOOMMM!!!!! One flick of the temperature and the NOZZLE indicator splashes over 10″, half an inch over the scale… A kick in the back – there we GO! Now I recognize you, magic Big Brooch! “Garda, 103, I’m climbing to about 20,000 feet and start the open nozzle descent…” At first, the Controller is not grabbing that the problem is real… He provides me a heading to lead me to the standard position for the training pattern, 10 miles south of the field. I check the directions he’s giving to me… NOT GOOD! I have to aim straight at the runway head, minus one turn radius, thus reckoning the runway threshold minus two miles… “NEGATIVE Garda… it’s a REAL emergency! Provide me a vector to the runway, from present position, please…!” Meanwhile my eyes keep scanning between altitude, speed, rpm and temperatures…15,000 ft, climbing.. I’m teasing the bearings with 100% RPM and maximum thrust! My hand wants to pull back on the throttle, but my head blocks it; the manual says that with the nozzles open, reducing the throttle under MAX AB, the afterburner might go off… The altimeter winds up through 20,000’; I’m in a heavy configuration, some extra altitude will turn out to be useful to me.

Enough! Throttle back to 83% RPM; T/O flap; for a moment I fly a ballistic path. Then we start the descent glide… a little more than 20 miles to go. I stabilize the speed to around 250kts, since 245kts would be optimal without external loads. Garda calls me, confirming that the altitude is just enough to guarantee arrival on the runway. The SOR comes on the frequency calling me. The squadron commander asks me to read the parameters. I read a couple of values, then I add: “Sir, the check list calls <EXTERNAL STORES JETTISON>; If I drop the pylon tanks, I might gain 20 points of glide ratio,” (the POD docking system would not allow me to eject it, while the tip tanks, with their winglets, added some lift)… The Boss replies sharply: “NO, don’t!…,” and then, “Tighten the seat harness and check the firing handle. Get ready to bail out…”

Wow! I’ve already checked everything twice; the hand has already gone twice to look for the lower ejection seat handle, clear from obstacles… If I need it, I’ll pull! But in the bottom of my heart, I don’t even think about it for a moment. I’m electrified by the tension, as if my tense determination, together with the obvious burst of adrenaline, could support my Starfighter’s wings in flight! I find myself peering through the haze – the gained altitude decreases dramatically, but the miles to safety are also decreasing. As I get closer, the TACAN needle will lean to the right, but I won’t be so foolish as to follow it, since its transmitting antenna is located at the far end of the runway. If I tighten the turn too much, cutting short, I will shift my touch down point at the end of the runway. I call Garda Radar for another vector. Now they have perfectly understood my intentions, we’re working in perfect harmony to “straighten the turn” one mile south of the runway…

“Altitude 4,000; distance 5 miles… 103 you are descending below the minimum gliding altitude.”

“I’m aware, but I can’t touch the engine anymore.”… Damn, I could have dropped the pylon tanks sooner, in the open countryside. Now I’m over a populated area…

For a moment, I focus upon the possible engine seizure. What if vibrations start developing? What would I do? Should I pull the RAT (Ram Air Turbine- an emergency hydraulic and electric power generator) so I won’t lose the hydraulic pressure and the flight controls? Not now, I don’t need extra drag! Eyes glued outside. Damn glaring mist. Where the hell is the runway?

Suddenly, out of the mist, pops the small tower of the Roveda hotel – slightly on the right… I know it’s a couple of miles southeast of the Base. I’m on the right spot!!!! I start the right turn, immediately… I growl on the radio “Garda, I’m starting the right turn”

I roll gently, but decidedly, to the right. The speed drops a bit; my crippled ‘104 starts sinking…

Airspeed 240… 230… decreasing… as the AOA is increasing, the control stick is kicked a little by the Shaker. I hold it as if it were a feather…220… Ahead to the right, I spot the bright “pine tree” (ALS- approach lighting system), of the landing path, coming out of the mist and finally… the RUNWAY!

I focus on that, to adjust the turn. I won’t move the flaps from T/O (the LAND position requires the engine over 83% to grant the forced blowing of the trailing edge flaps). I’ll lower the landing gear only on very short final… I have to make it… speed… runway… speed 215, still turning… altitude 800’… I can make it!… 210… I have simulated this situation many times… I end the turn under 500 feet, shaker bursts, I’m in… Wings leveled, 200kts… Perfectly aligned on the centerline, the left hand grabs the landing gear lever – over the fence, wheels down NOW! Clunk, the doors, Madonna! You must lock down quickly! I don’t know why, but my hand runs to the emergency gear handle… but a loud THUD! and three green lights confirm the completion of the gear-locking sequence…

“Garda 103, three green, landing…” Runway threshold, throttle idle. I pull a whisker of stick to pull the nose up, speed brakes out, to ease the touchdown. The wheels are on the “comb” markings… Nose wheel down, speed under 190, drag chute, I feel it tug hard; it has deployed… The speed’s decreasing… brakes. I see the fire-fighting and rescue vehicles leaving their positions out of the corner of my eye – their lights flashing as they launching themselves in my pursuit… The radio, silent in that last phase, now comes back to life…

From the SOR, again the squadron commander growls, “Sardo, all OK? You need something?”

For a moment, the hierarchical respect suggests a formal answer, but the real part of me takes over and my voice blurts out, “Yes please, a clean underwear change!”

Suddenly other missions enter the frequency; now at minimum fuel, they were waiting to decide whether to divert to the alternate or land at home base. I’m still on the runway – speed under control – I tighten the stick grip, my ring finger on the steering button. With the inertia, I clear the runway at the 45° intersection and call: “Garda 103 runway vacated… Emergency ended”

The firefighters are all around my ‘104; now I can cut the engine. We’re definitely at a standstill now! As I press my toes on the brake pedals, I realize that my calves are fibrillating; I’m shaking…

With the wheel chocks installed, I switch the radios off, then move the throttle to STOP. Suddenly my plane fades all life; the engine RPM drops with a gloomy rumble. I turn the seat safety swivel guard, release the leg straps, then with a punch on the lock box I untie the belts. I swing the canopy open and lock it in place; now I need fresh air! I disconnect the emergency radio and the boat lanyard and lose the oxygen hose connector. I stand up on the seat, but the ground crew gesture for me to wait for the ladder… No, I WANT TO GET OUT NOW!!

At that moment I hear a BLASTING roar; a 104 flying low – VERY LOW AND FAST – over the parallel taxiway, mixing its wake with the hot exhaust fumes, which curl up on the asphalt, along the junction. It passes in front of me, the cockpit at the same level of my face, then pulls up straight into the vertical. Its exhaust cone lights up; thunder from the afterburner shaking everything. It rolls into a victory roll. It’s ‘Grandpa’ Collenz, one of our senior pilots, who greets me in his own way, for having escaped the danger.

I sit on the edge of the cockpit, with the tears in my eyes, and let myself slide onto the ground down the side of the fuselage. As I touch the ground, everything seems to weigh a ton – the helmet, the life jacket. My knees are weak; they’re shaking and can’t support me. I fall down on my knees, and stay like this for a moment. Then I sit down – under the nose of my 104 – my back leaning on the nose gear… I look at her and she looks down at me from above. She took me home, without any oil left, without engine thrust – gliding like a sailplane. Old evil “brooch”, we’re back home…

The base commander comes in – the Colonel – with his blue staff car. I should get up, salute him, but I can’t do it. He doesn’t seem to care much. He looks up at the climbing Starfighter, then he swears, “Who the hell is that?!! Is he crazy…??!!” The squadron boss joins; he hugs me and tells me that he was staring at my final turn. He’s a former instructor from Grosseto, the F-104 OCU, and his words fill me with pride… “I saw the final turn, a masterpiece… You paint-brushed the plane straight to the runway. You leveled the wings off, and the plane was on the ground. How great!”

Sitting in the car, I glimpse a small tractor towing my ‘104 towards the maintenance center, and at the bottom of my heart I feel there, almost as if I wanted to take an old sick friend to the hospital.

The aftermath seems to take place with exasperating torpidity; the medical examination for the inhaled fumes, the eye drops, the Flight Safety report, the technical investigation, the toast at the O-Club for the healthy dose of “f***ing luck” I had… It was not easy to remove the engine from the fuselage for inspection; the exhaust nozzle ‘turkey feathers’ were so spread open so wide that it was nearly impossible to get the tail-end out. Then, finally, came the technical investigation; it showed the seizure of the oil scavenge pump front bearing (Scavenge Pump No.1), the failure of the seal rings due to overpressure; all of the oil sprayed at once in the compressor. From here, some of the oil was pushed into the air conditioning system and from there, into the cockpit. Once the generators were disconnected, I lost all warnings about the low level of the oil – for a short time – but long enough to exceed the minimum level of 4 pints, and consequently the emergency reservoir as well. The ‘red handle’ was working on “empty” at that point. The bearings were already dry and had worked without any oil for about 9 minutes, of which at least 3 minutes were at 100%, with the afterburner, exceeding the manual’s requirements. Bless my good old General Electric J-79-GE-11-A engine – you wouldn’t have lasted much longer anyway, but you brought me home…Thank you!!!

When the official incident report for the Air Staff in Rome was finished, its writer, perhaps more used to office chairs than ejection seats, attributed a modicum of blame to the pilot, who he said “had not been able to promptly recognize the smell of the sprayed oil from the electric smoke, adopting a procedure not perfectly suitable for the resolution of the emergency”… In my heart, I didn’t even think about arguing that idiocy; I probably wouldn’t have received any praise anyway. In my candid, youthful enthusiasm – more than any other formal recognition – I was taken by the adrenaline of the story, the sense of anguished helplessness linked to the image of the altimeter in its merciless descent, the unshakeable determination to get the plane back on the runway, the final turn on the brink of the “stick shaker” stall warning, the greeting of Grandpa Collenz, the embrace and the kind words of the Boss, and former F-104 instructor…

For many nights I have reviewed, with my eyes wide open in the dark, the whole sequence, adding each time a different “what if…???” What if I interrupted the climb a little earlier? What if I had followed the TACAN indication, finding myself too far away or too close to the runway? What if in the final phase, in the middle of the turn, the engine had seized? The sudden blockage of the whole compressor and turbine shaft, weighing over a ton, would have created an uncontrollable torque, able to roll the plane to the right, taking away any chance of escape… The nightmares I experienced with my eyes wide open only populated my nights for a short time, because, as in the best aeronautical traditions, I started flying again immediately, before the fears could grab and wrap around my soul. Now, years later, after so many other flying adventures, after having ridden other aircraft, there remains a visceral love never dormant for the “Brooch ‘104”, a nostalgic bond of love and reverential respect for a wonderful thoroughbred, with whom I had the honor to share over a thousand hours of glorious purity, far from the earth…Superb!

About Brigadier General Roberto Sardo

After commanding the 28th Squadron as a Lieutenant Colonel, he moved to the Air Staff in Rome first, then Vicenza Opr Command, where he led the planning and organizing teams for the Air Force main Air Exercises. Until 2005, he was allowed to fly the AMX as a safety/check pilot at his former unit, with a 50% reduced flight time, compared to the full time operational pilots. Pinned as Full Bird Colonel, from 2005 to 2008, he assumed command of Aviano ItAF Base, hosting the USAF 31st FW. Among his responsibilities there, he had to smooth out all of the legal, political, environmental and standardization problems which arose. This effort was partly compensated with some back seat rides with the F-16s of the USAF 555th and 510th Fighter Squadrons.

The next 4 years were spent as head of Combat Support Branch at the NATO Joint Air Power Competence Center in Kalkar (DEU), with the task of enhancing the standardization and interoperability of NATO Units concerning Airlift, Combat SAR/Personnel Recovery and Air-to-Air Refueling capabilities. In 2012, he was re-assigned to the ItAF Air Warfare College in Florence as the Officers Classes Commander, until his retirement in 2015. With the honorary title of Brigadier General (as a consolidated tradition in the Italian Armed Forces, Officers receive an honorary promotion the day before retirement), Roberto Sardo is still enjoying full time flying as a civilian flight instructor, glider pilot and owns a STOL Slepcev Storch, a replica of the famous WWII-era Fieseler Fi 156 Storch. He has three grown children and, from his father, he inherited two WWII Willys MB Jeeps and other collectible cars.

Many thanks indeed to General Sardo for his breathtaking account of surviving a serious incident in the F-104 Starfighter. We feel sure our readers will have found his story a fascinating read!

Pilot Report: As noted earlier, we will publish further accounts from time-to-time, but are eager to record more for the future. If any readers are interested in sharing their own memories and stories with us, please do contact us HERE.

Related Articles

Richard Mallory Allnutt's aviation passion ignited at the 1974 Farnborough Airshow. Raised in 1970s Britain, he was immersed in WWII aviation lore. Moving to Washington DC, he frequented the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum, meeting aviation legends.

After grad school, Richard worked for Lockheed-Martin but stayed devoted to aviation, volunteering at museums and honing his photography skills. In 2013, he became the founding editor of Warbirds News, now Vintage Aviation News. With around 800 articles written, he focuses on supporting grassroots aviation groups.

Richard values the connections made in the aviation community and is proud to help grow Vintage Aviation News.