By Adam Estes

Among WWII aviation enthusiasts, the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum (NASM) is renowned for possessing some of the rarest German and Japanese aircraft of that conflict, many of which are the last of their kind. But nestled among their ranks is the only Italian aircraft of WWII in the museum’s collection, a now exceedingly rare Macchi C.202 Folgore (Thunderbolt). But while the NASM’s Folgore is in excellent condition following a restoration during the early 1970s, its individual history has long been murky. However, thanks to new research in both Italy and the United States, the Smithsonian may finally get a better insight into the wartime history of their Folgore during its time in the Regia Aeronautica (Royal Italian Air Force), and in learning how and when it was brought to the United States.

Developed from the Macchi C.200 Saetta (Arrow), and conceived by Macchi’s lead designer, Mario Castoldi (hence the C in C.202), the Folgore was powered by a licensed development of the Daimler-Benz DB-601 inverted V12 engine, the Alfa-Romeo Monsone (Monsoon). The armament consisted of four Breda-SAFAT machine guns (two 12.7mm guns in the nose, and two 7.7mm guns in the wings). One distinguishing feature of the Folgore was the fact that its left wing was extended by 21 centimeters (8.5 inches) to counteract the torque from the Monsone engine.

First flown on August 10th, 1940, the type would enter service with the Regia Aeronautica the following year, and would see combat from the deserts of Libya to the outskirts of Stalingrad. While its speed and agility were commended by both friend and foe alike, the Folgore’s standard armament proved ineffective by 1943 with other fighters being equipped with powerful guns and cannons. This combined with the introduction of a licensed development of the Daimler-Benz DB-605, the Fiat Tifone (Typhoon), would see the introduction of more powerful aircraft, such as the Macchi C.205 Veltro (Greyhound) and the Fiat G.55 Centauro (Centaur), which were also armed with German MG 151 20mm cannons. Yet as these new fighters were being developed, the Folgore was still the frontline fighter for many Italian squadrons during the Allied landings in Sicily and mainland Italy up to the dissolution of Benito Mussolini’s government by both his own fascist council and King Victor Emmanuel III in July of 1943.

Following Italy’s formal surrender to the Allies in September of 1943, the nation was divided between the now Allied-aligned Kingdom of Italy (or Co-Belligerent government), which controlled the south, and the Italian Social Republic, a German-puppet state in the north with Mussolini placed ostensibly in charge following his daring rescue by German commandos during the Gran Sasso Raid on September 12th, 1943. Folgores flew in the air forces of both Italies, but since the policy of the Cobelligerent Air Force (Aviazione Cobelligerante Italiana, ACI*) was to fly in combat only in the Balkans to avoid confusion with similar aircraft of the National Republican Air Force (Aeronautica Nazionale Repubblicana, ANR), there were no reported instances of any opposing Italian aircraft, let alone Folgores, encountering each other.

*It’s worth mentioning that The name “Italian Cobelligerent Air Force” and other similar acronyms, both in Italian and English, have no confirmation in the documents of the time and have been used in the past by some historians and commentators. Officially the Regia Aeronautica changed its name to the Italian Air Force on 18 June 1946.

Several Folgores would remain in postwar service, however, as training aircraft in the Italian Air Force until 1948. Some of these were even rebuilt as C.205 Veltros, and often little to no effort was given to distinguish these hybrids from the genuine wartime Veltros. Many of these hybrid Veltros were later exported to Egypt where they clashed against the nascent Israeli Air Force during that country’s 1948-1949 War for Independence, and many of the few surviving Veltros today have at least a fair number of Folgore components in them, or were originally built as Folgores. In the end, though, only two complete C.202 Folgores remain; one in the Italian Air Force Museum on the shores of Lake Bracciano in Vigna di Valle and the focus of this article, the example held in the collection of the NASM.

Much like the museum’s Messerschmitt Bf 109G-6/R3 (as previously reported by Vintage Aviation News), this Folgore was flight tested by the USAAF after its capture during the war and was later set aside for preservation for what would become the NASM. However also like their Bf 109, though, the museum lacked any information on the Folgore’s provenance other than the USAAF evaluation reports when it was flight tested at Wright Field in Dayton, OH, and Freeman Field near Seymour, IN from 1943 to 1945. Because the aircraft’s original Matricola Militare (MM, the aircraft’s military registration) number was missing from these records the museum had no idea about the nature of their Folgore’s service in the Regia Aeronautica. Indeed, before the aircraft’s restoration began in 1974, it was still wearing the spurious Italian scheme painted by the USAAF back in WWII.

In light of this, then-curator Robert C. Mikesh concluded that if the wartime identities of certain aircraft could not be definitively determined then they should at least accurately represent a scheme worn on a known aircraft. Upon reviewing wartime photos of Folgores and having reached out to contacts in Italy who were now researching the aircraft of the Regia Aeronautica and their markings, it was decided to paint the NASM Folgore in the markings of 90-4, an aircraft that was attached to the 90th Squadriglia (Squadron), 10th Gruppo (Group), 4th Stormo (Flight). This was despite the fact that although the Italian serial number painted on the aircraft was MM.9476 of the Serie IX production line, the real 90-4 was in fact MM.7798 of the Serie III line. Other than this detail, though, the paint work was in line with the latest research on Italian aircraft stencils and paint schemes up until that time.

Once the restoration was completed in 1975, the aircraft was then transported to the new NASM building on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. and was suspended from the ceiling of the World War II in the Air gallery by the time of the opening ceremony on July 1st, 1976. For millions of visitors from around the world over the next 40-plus years, this is how the Folgore appeared to them. But in the spring of 2019, during the currently-ongoing renovations to the Mall facility, the Folgore and many other historic aircraft and spacecraft were transported to newly constructed storage facilities at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, VA to make way for improvements to the museum facilities and future display. While many of these aircraft and spacecraft have returned to the Mall and have been on public display since 2022, others are in the process of being refurbished and prepared for their return by road to downtown D.C., and others still will stay at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center for display there. For the museum’s Folgore, however, this period of time has presented a window to look further into the exact nature of its origins and to determine how it came to be in the United States.

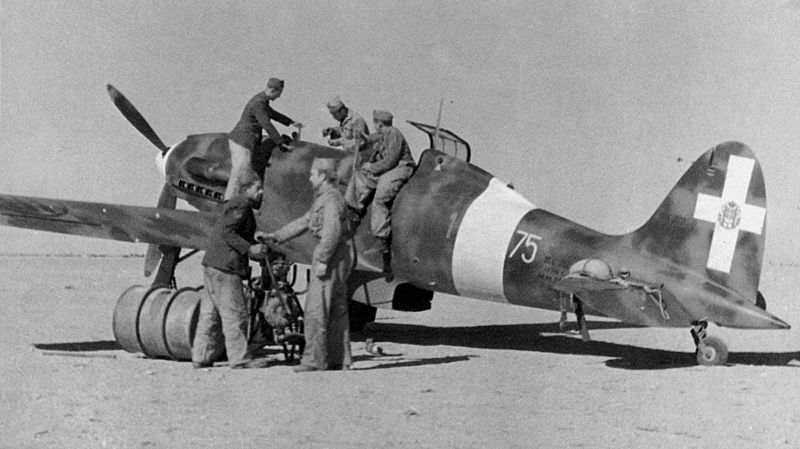

From the fluorescent lights of the Udvar-Hazy Center’s storage facilities, we travel eighty years back in time to see a dusty sun-baked field outside the Sicilian town of Sciacca, filled with abandoned fighters of the Regia Aeronautica in the wake of the Allied landings in Sicily. British field intelligence had arrived here and would document a total of 122 aircraft, from Reggiane Re.2001s and Messerschmitt Bf 109Gs in Italian colors to several Macchi C.200 Saettas of the Regia Aeronautica’s 157th Fighter Group and about a dozen Folgores of the 21st Autonomous Group. These reports then made their way to a makeshift airfield near Termini Imerese, some 20 miles east of Palermo, on the northern coast of Sicily and some 46 miles (75 kilometers) north of Sciacca, on the island’s southern coast. There, pilots of the U.S. 12th Air Force’s 31st Fighter Group (consisting of the 307th, 308th, and 309th Fighter Squadrons), equipped with Spitfire Mk.IXs, decided to go down to Sciacca and bring home some “war trophies” during a lull in the recent fighting.

The 31st Fighter Group had originally served in England with the VIII Fighter Command, escorting the bombers of the 8th Air Force across the English Channel on their way to and from raids into Nazi-occupied Europe before their transfer to the 12th Air Force in support of the Allied landings in North Africa codenamed Operation Torch. Having fought their way through North Africa, the 31st FG would become the first American fighter group to establish itself in Sicily after fighting its way through North Africa. The progress of the allied ground forces also resulted in the 31st FG being forced to make hasty moves to newly-captured airfields to keep pace with the ground forces they were providing fighter cover for, while the Army Corps of Engineers was tasked with going out ahead of the fighter groups and preparing their airfields, often nothing more than dusty strips of land, for flight operations.

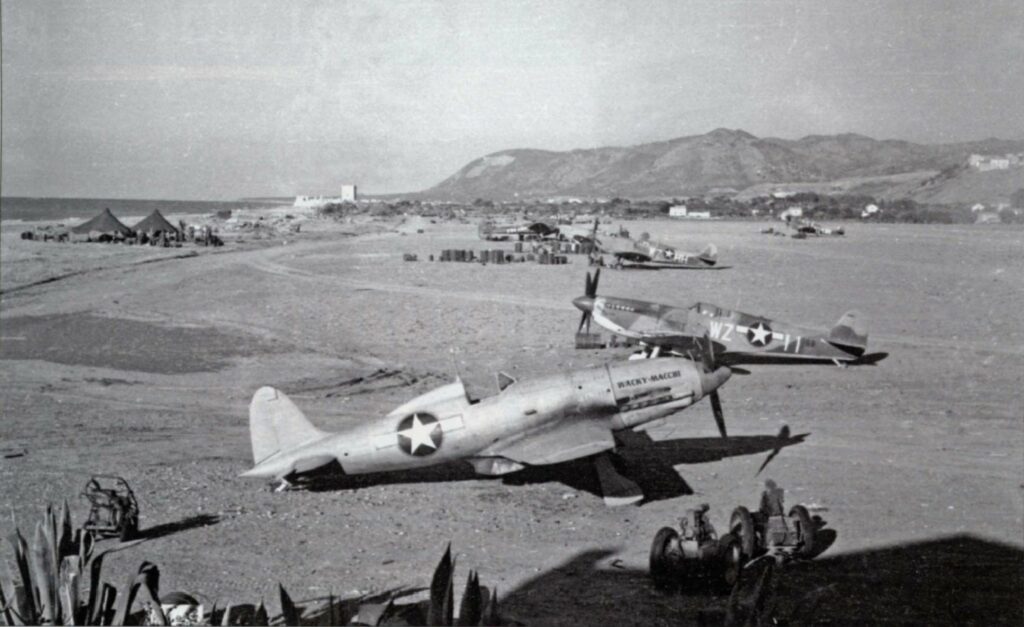

When the men of the 31st’s 309th Fighter Squadron arrived at Sciacca, they found that just as the British reports had indicated, there were two C.202 Folgores capable of being returned to airworthiness. They were brought to Termini Imerese, where at least one of the Folgores was then repainted in American markings patterned off of their own Spitfires. The propeller spinner was painted red, the wings and fuselage desert tan, and the underside was given a light blue scheme. To complete the repaint, the men of the 309th FS named their prize Wacky-Macchi, adding the name to both sides of the engine cowling, and painting the squadron’s insignia featuring the Disney cartoon character Donald Duck on the side of the fuselage near the cockpit.

Some of the American pilots would even fly the Wacky-Macchi on joyrides when they weren’t flying combat missions in their Spitfires, most notably Lieutenant Dale E. Shafer of the 309th FS, who was one of the pilots most influential in returning the Wacky-Macchi to the air. For the men of the 309th, it was an opportunity to fly a type of aircraft they had engaged in combat prior to securing the skies above Sicily. However, the 31st Fighter Group was to be reassigned in September of 1943 to Milazzo, on the northeastern corner of Sicily in preparation for supporting the upcoming Allied landings on mainland Italy at Salerno. Later, the 31st Fighter Group was transferred to the 15th Air Force and flew the P-51 Mustang for the remainder of the war. The move to Milazzo would also mark the departure of the Wacky-Macchi from the 31st Fighter Group. But that leaves two questions: where did the Wacky-Macchi go, and is the Wacky-Macchi the same C.202 that now sits in the Smithsonian?

Across the Atlantic and back in the present day, Italian aviation historian Giovanni Massimello became intrigued with the story of the Wacky-Macchi and that of the aircraft in the NASM. He looked up the British intelligence reports from Sciacca taken in August of 1943, which recorded the Italian markings of both serial numbers and squadron codes painted on the fuselages of the Folgores. All of the C.202s whose numbers were recorded were assigned to the 356a Squadriglia (squadron) of the 21° Gruppo Autonomo C.T. (autonomous group; ‘C.T.’ standing for caccia terrestre or land fighter), and the two aircraft listed by the British as being in “good condition” were identified as registration number MM.91981/squadron code 356-8 and MM.91825/356-6.

The 21° Gruppo Autonomo C.T. had been engaged in combat on the Eastern Front against the Soviet Air Force up until it was recalled to Italy in the spring of 1943, being stationed at Peretola, the site of the modern Florence Airport. In June of that same year, the group was assigned new aircraft fresh from the factories. Among these were MM.91981, which came out of the Aeronautica Macchi factory in Varese, and was accepted into the 356th on June 19. On June 25th, the 356th took delivery of MM.91825, which had been produced by the Breda Aeronautica factory in Sesto San Giovanni. That same month, the 21° Gruppo Autonomo and the 356a Squadriglia were sent to Sicily and, though they had their center of operations based at Trapani-Chinisia airfield, detachments of the 21° Gruppo Autonomo were sent to other nearby airfields in light of the speed of the Allied advance through Sicily, which is how Folgores MM.91981 and MM.91825 came found abandoned at Sciacca.

Being certain that at least one of the two Folgores from Sciacca was later brought to the United States, another question Massimello had to answer, though, was which aircraft would become marked by the Americans as Wacky-Macchi. When either the Macchi-built MM.91981 (356-8) or the Breda-built MM.91825 (356-6) was repainted by the men of the 31st Fighter Group, all traces of the Italian unit markings on the fuselages and tail surfaces were now covered in the same overall desert scheme that appeared on the 31st’s Spitfires. However, the propeller blades of the Wacky-Macchi were not repainted, and a color photograph taken at Termini Imerese would indicate the winged emblem of Aeronautica Macchi. Another photograph, taken of Lt. Claude McRaven (generously provided to the author by his son, Admiral William H. McRaven) of the 309th Fighter Squadron, would also show the Macchi logo on the propellers of the Wacky-Macchi, clearly distinguishing it from the circular logo applied on the propellers of Breda-built Folgores. This would make it safe to assume that MM.91981, the Macchi-built aircraft captured at Sciacca, was the Wacky-Macchi.

With the Allies securing Sicily and readying themselves for the amphibious invasion of southern Italy, a C.202 Folgore would arrive at the Evaluation Branch of the Air Technical Service Command at Wright Field in Dayton, OH by August 20th, 1943 where it received the USAAF serial EB-300. According to British researcher Phil Butler in his book War Prizes: An illustrated Survey of German, Italian and Japanese Aircraft Brought to Allied Countries During and After the Second World War, EB-300 was later shipped to the USAAF’s Air Service Command facility at Tulsa, OK for overhauling on March 27th, 1944. The facility in Tulsa was originally built for the Spartan Aircraft Company and the Spartan School of Aeronautics in the pre-war years. By the time the aircraft returned to Wright Field by May 15th, 1944, the Evaluation Branch had been reformed as the Foreign Equipment Branch, and the aircraft was reserialed as FE-300 and used for flight evaluation against American fighter aircraft and other captured aircraft of German and Japanese origin.

It should also be noted that Phil Butler discovered that a second C.202 arrived at Wright Field on November 27th, 1943, and was used as a source of spare parts. There is a possibility that this might also have been one of the Sciacca Folgores brought to Termini Imerese by the 31st FG but, without further information, no one can say for certain whether or not this is the case. Returning to the story of FE-300, the aircraft spent the remainder of the war being flown at Wright Field and at another airfield used by the Foreign Equipment Branch for evaluation flights, Freeman Army Airfield near Seymour, Indiana. Created in 1942 and named for Captain Richard S. Freeman, who was killed in the crash of a Boeing B-17B Flying Fortress in Nevada in 1941, Freeman Field had been used as a training field by numerous elements of the USAAF and was made available for the Foreign Aircraft Evaluation Center by June 1945, in time for new arrivals of German jet and late-war piston aircraft brought over through Operation LUSTY (LUftwaffe Secret TechnologY) such as Messerschmitt Me 262s, Arado Ar 234s, and Heinkel He 162s. When the war finally ended with the formal surrender of Japan in September 1945, a large airshow was hosted at Freeman Field featuring all kinds of fighters, bombers, and transports of American, British, German and Japanese manufacture, with the only Italian aircraft displayed on the flight line being the Macchi C.202 Folgore, having been renumbered as FE-498 some time prior, where it was photographed by many spectators and served as a backdrop for several pictures of young American servicemen in their “pink and green” service uniforms.

With the war’s conclusion in 1945, FE-498 would be reserialed for the final time as T2-498 in April 1946 following the reorganization of the Foreign Equipment Branch into the T-2 Office of Air Force Intelligence. By this point, though, the Folgore was no longer needed for evaluation and the FE- code was never painted over with the T2- code on the aircraft’s surface. That same year the Folgore ordered to be transferred to the 803rd Special Depot, based at a former Douglas C-54 factory built during the war at Chicago’s Orchard Place Airport (later to be renamed as O’Hare International Airport in honor of U.S. Navy ace and Medal of Honor recipient Edward “Butch” O’Hare), alongside other Allied and Axis aircraft that were to be allocated for “museum duties” under the express wishes of USAAF Chief of Staff General Henry “Hap” Arnold. The Folgore would be disassembled, packed into shipping crates and transported to Orchard Place, arriving there in August of 1946.

That same month, on August 12th, President Harry Truman signed a bill into law that would establish a National Air Museum under the provision of the Smithsonian Institution. Among the bill’s strongest proponents were General Arnold and Smithsonian curator Paul E. Garber, who had made it his life’s mission to preserve as many aircraft as possible for the Smithsonian, and would become the first Head Curator of the NAM (later to be reformed as the NASM). With personal ties to General Arnold, Garber was able to ensure that the vast collection of surplus Allied and captured Axis aircraft would be held in storage until a permanent structure for the National Air Museum could be established.

At that time, the Smithsonian’s aeronautical collection was held either within the halls of the Smithsonian’s Arts and Industries Building (built in 1881), alongside other exhibits that would be displayed in later museums such as the National Museum of American History, or in the Aircraft Building, a metal structure originally meant to be a temporary building for the US Army during WWI that was nicknamed the Tin Shed, and which was already running out of space for new aircraft displays. Garber was persistent in the need for a new and permanent facility for the National Air Museum but although the Smithsonian was (and remains) publicly funded, there was a lack of interest among the outside forces necessary to lend the finances to build a museum, so the WWII aircraft were kept at Orchard Place for the time being.

Time would not come soon enough, though, for in 1951, with the Korean War raging on, the Air Force felt that the Orchard Place plant should be handed back from the Smithsonian, giving the Smithsonian only a few months to vacate the building with dozens of airplanes in tow. Most of these planes (including the Macchi C.202) were successfully moved out, but a few airplanes either lost key components such as their wings during the shipment process or were scrapped entirely when they could not be moved out quickly enough. Despite this setback, Garber was able to find a plot of surplus government land near Suitland, Maryland, just southeast of Washington, D.C. that could be cleared out and made ready for the storage of these aircraft. Originally called the Silver Hill Facility, it would eventually come to be named the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility in honor of Garber, whose vision was vital to the current status of the NASM as one of the world’s most popular museums. But Garber’s vision was often more far-reaching than the funds he was forced to work with, and many priceless aircraft were forced to endure sitting outside through humid summers and freezing winters, sometimes with nothing more than tarps to protect them from the elements as proposals for museum buildings on the National Mall were presented and rejected for nearly twenty years. But as indoor storage buildings were being constructed at Silver Hill, a proposal for a permanent building was finally agreed upon, and construction of the National Air and Space Museum building began in earnest in 1972.

With the deadline for completion set for the nation’s Bicentennial celebrations in July 1976, curators and restoration specialists scrambled to get a selected number of aircraft ready for display. From 1974 to 1975, with consultation from Aermacchi (formerly Aeronautica Macchi) and the General Staff of the Italian Air Force to provide reference materials, the Macchi C.202 Folgore was made ready for display with a new paint scheme and the serial number of MM.9476, and the aircraft was placed in the new museum’s World War II in the Air gallery, alongside the museum’s North American P-51D Mustang, Supermarine Spitfire Mk. VIIc, Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6, Mitsubishi A6M5 Model 52 Zero, and the nose section of the Martin B-26B Marauder Flak-Bait, which flew more missions than any other American bomber of WWII.

Besides the Smithsonian’s Folgore, another Macchi C.202 mentioned earlier in this article is on display in the Italian Air Force Museum in Vigna di Valle, on the shores of Lake Bracciano. This aircraft was manufactured by Breda in 1943 and allocated to the 5° Stormo of the Co-Belligerent Air Force. After the war the aircraft was used as an instructional airframe at the Italian Naval Academy (Accademia Navale) in Livorno and with the University of Pisa’s Engineering Department before its donation to the museum and subsequent restoration. It is likely that parts of several C.205 Veltros were fitted to the aircraft during its service life, namely the propeller spinner and engine cowling, respectively. Today, the aircraft is displayed wearing the markings of a Folgore flown by Italian ace Giulio Reiner (1915-2002). Next to it is a C.205 Veltro originally built as a Folgore before its conversion to the standard of a Veltro with the inclusion of a DB-605/Fiat Tifone engine. There is also a reproduction of a Folgore at the Volandia Park and Museum of Flight, adjacent to the Milan-Malpensa Airport, and as mentioned previously, several aircraft displayed as C.205 Veltros were in fact originally built as Folgores before their engines and armaments were upgraded to the standards of the C.205s.

The lack of definitive documentation relating to the aircraft known as Wacky-Macchi has also led to differing conclusions to the markings and Italian identity of the Folgore in question. For example, some artists interpretations of the Wacky-Macchi scheme show not the Daffy Duck emblem of the 309th Fighter Squadron but instead a tomahawk-wielding American Indian, while other websites have claimed that the Italian serial number of the Wacky-Macchi was MM.91975. According to Massimello, MM.91975 was first tested on July 17th, 1943 at Lonate-Pozzolo before its delivery to the 97th Squadron, 9th Group, 4th Wing on May 27th as aircraft number 3. Furthermore, after the armistice of September 1943 it was reassigned to the 209th Squadron of the Co-Belligerent Air Force. Given this, it seems unlikely that MM.91975 is the aircraft in the Smithsonian.

Today, the Smithsonian’s Folgore is being kept in storage at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center. When the renovations to the National Mall museum building in Washington, D.C. have been concluded by 2026, museum curators will have finally had time to evaluate the Folgore once again to determine the best course of action for its return to display. With information on where to find any potentially overlooked dataplates that mark the aircraft’s serial number provided by Massimello to the Smithsonian, museum officials may yet be able to conclusively prove once and for all the definitive identity of this aircraft, and learn whether it is a Macchi-built or a Breda-built example. Such definitive findings may also lead to a possible second restoration on the Folgore, much like the Messerschmitt Bf 109 now being restored with its recently-discovered Luftwaffe markings for its return to D.C. by 2026.

The author would like to extend his gratitude to Giovanni Massimello for his work in the article From Sicily to Washington, published in the February 2019 issue of the publication Storia Militare and for his correspondence and contributions towards the production of this article. Further credit to Dr. Alex Spencer, curator of the National Air and Space Museum’s European military aircraft collection, who has provided valuable information on the current status of the Folgore.

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.

Excellent story

But:

1. CT stands for CACCIA TERRESTRE, as in Land-based Fighter (Unit)

2. there’s no such thing as Italian Co-belligerent AF: the contemporary ItAF simply kept its then-current Regia Aeronautica moniker (Royal Air Force) throughout the armistice-senctioned operations and until 1946, when Italians voted for the country to become a republic

Regards

FC

Thank you for the correction. The article has been updated accordingly.

Just wanted to add some information. Many years ago I aquired a M202 tail gear from someone who found it metal detecting at the old Orchard Place Airport. It has a dataplate with a serial number ending in 980 with a manufacture date of 30.11.42. Ive kept it all these years as I am an aviation enthusiast and grew in italy. If anyone would like photos, be glad to share.

Hi James, I would be very interested in seeing the photos of that data plate. I would also like to pass this information along to Dr. Alex Spencer, the Smithsonian curator I worked with for this article. He has been very interested in finding any information on the Folgore.

Could anyone please give info on the coat of arms with the logo “Return With Honor”?

Hi Bob. As per the photo caption that’s the squadron emblem of the USAAF 31st Fighter Group.

Hi Adam

Be glad to. Send me an email and will send you some pics.

James

I think there is a good chance the Smithsonian C.202 is MM 9695, a Breda-built Serie XII coded 91-7. There is a color video clip on Critical Past showing the aircraft being inspected by Americans on August 14, 1943 at Fontanarossa Airport, Catania, Sicily. It appears to be in excellent condition, except for damage to the right wing faring where the wing attaches to the fuselage. The structure beneath has minor damage. I would be interesting to inspect the Smithsonian C.202 for signs of repair to the faring or structure underneath. The video can be found on CriticalPast.com as clip 65675061167.

I almost bought the C.202 tailwheel fork that James has. The seller lived close by, so I could have picked it up and saved the shipping cost. Anyway, just some additional information from when I was looking at it. The tailwheel fork came from the Freeman Field Foreign Aircraft Evaluation Center in Seymour, Indiana. It was recovered from a dump pit by the Freeman Field Recovery Team around 2009. They also recovered a Piaggio P.1001 propeller blade at that time. I believe that the Freeman Army Airfield Museum still has that. In November 1945, all flyable aircraft were moved from Freeman to Orchard Field in Chicago, Illinois (now Chicago O’Hare International Airport). The disassembled parts left at Freeman were buried in October 1946.