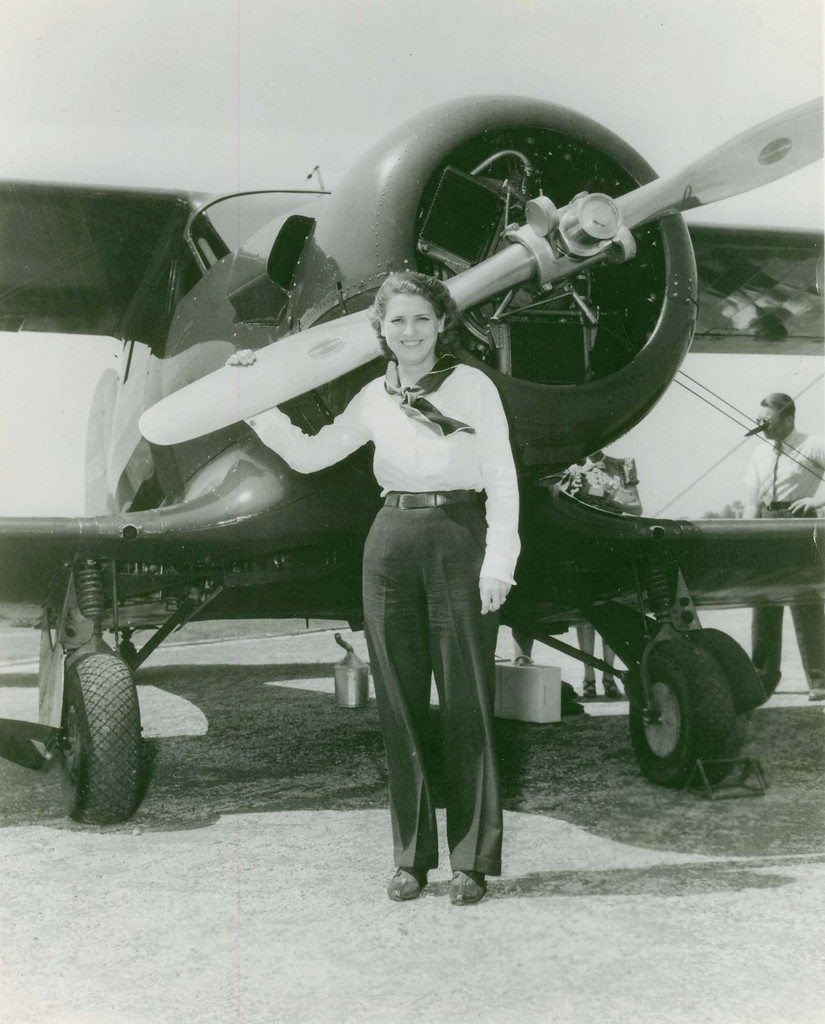

Jacqueline Cochran’s life was about risk and about triumph. A successful businesswoman and director of the Women’s Air Force Service Pilots in World War II, at the time of her death Cochran held more speed, altitude, and distance records than any other pilot, female or male. On August 9, 1980, Jacqueline “Jackie” Cochran, Colonel, United States Air Force Reserve, passed away at her home in Indio, CA, at the age of 74. Jackie was truly a giant of aviation.

The following is the official U.S. Air Force biography

Jacqueline “Jackie” Cochran was a leading aviatrix who promoted an independent Air Force and was the director of women’s flying training for the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots program during World War II. She held more speed, altitude, and distance records than any other male or female pilot in aviation history at the time of her death.

She was born between 1905 and 1908 in Florida. Orphaned at an early age, she spent her childhood moving from one town to another with her foster family. At 13, she became a beauty operator in the salon she first cleaned. Eventually, she rose to the top of her profession, owning a prestigious salon, and establishing her own cosmetics company. She learned to fly at the suggestion of her future husband, millionaire Floyd Odlum, to travel more efficiently. In 1932, she received her license after only three weeks of lessons and immediately pursued advanced instruction. Cochran set three major flying records in 1937 and won the prestigious Bendix Race in 1938.

As a test pilot, she flew and tested the first turbo-supercharger ever installed on an aircraft engine in 1934. During the following two years, she became the first person to fly and test the forerunner to the Pratt & Whitney 1340 and 1535 engines. In 1938, she flew and tested the first wet wing ever installed on an aircraft. With Dr. Randolph Lovelace, she helped design the first oxygen mask, and then became the first person to fly above 20,000 feet wearing one.

In 1940, she made the first flight on the Republic P-43 and recommended a longer tail wheel installation, which was later installed on all P-47 aircraft. Between 1935 and 1942, she flew many experimental flights for Sperry Corp., testing gyro instruments.

Cochran was hooked on flying. She set three-speed records, won the Clifford Burke Harmon trophy three times, and set a world altitude record of 33,000 feet – all before 1940. In the year 1941, Cochran captured aviation first when she became the first woman pilot to pilot a military bomber across the Atlantic Ocean.

With World War II on the horizon, Cochran talked Eleanor Roosevelt into the necessity of women pilots in the coming war effort. Cochran was soon recruiting women pilots to ferry planes for the British Ferry Command and became the first female trans-Atlantic bomber pilot. While Cochran was in Britain, another renowned female pilot, Nancy Harkness Love, suggested the establishment of a small ferrying squadron of trained female pilots. The proposal was ultimately approved. Almost simultaneously, Gen. H.H. Arnold asked Cochran to return to the U.S. to establish a program to train women to fly. In August of 1943, the two schemes merged under Cochran’s leadership. They became the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots.

She recruited more than 1,000 Women’s Airforce Service Pilots and supervised their training and service until they were disbanded in 1944. More than 25,000 applied for training, 1,830 were accepted and 1,074 made it through a very tough program to graduation. These women flew approximately 60 million miles for the Army Air Force with only 38 fatalities, or about 1 for every 16,000 hours flown. Cochran was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for services to her country during World War II.

She went on to be a press correspondent and was present at the surrender of Japanese General Yamashita, was the first U.S. woman to set foot in Japan after the war, and then went on to China, Russia, Germany, and the Nuremberg trials. In 1948 she became a member of the independent Air Force as a lieutenant colonel in the Reserve. She had various assignments which included working on sensitive projects important to the defense.

Flying was still her passion, and with the onset of the jet age, there were new planes to fly. Access to jet aircraft was mainly restricted to military personnel, but Cochran, with the assistance of her friend Gen. Chuck Yeager, became the first woman to break the sound barrier in an F-86 Sabre Jet owned by the company in 1953 and went on to set a world speed record of 1,429 mph in 1964.

Cochran retired from the Reserve in 1970 as a colonel. After heart problems and a pacemaker stopped her fast-flying activities at the age of 70, Cochran took up soaring. In 1971, she was named Honorary Fellow, Society of Experimental Test Pilots, and inducted into the Aviation Hall of Fame.

She wrote her autobiography, “The Autobiography of the Greatest Woman Pilot in Aviation History” with Maryann B. Brinley (Bantam Books). After her husband died in 1976, her health deteriorated rapidly and she died Aug. 10, 1980.

Sources compiled from the Air Force Flight Test Center Office of History and Air Force Reserve Command.

Related Articles

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.