When the United States entered WWI as a belligerent power when it declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, it had no airplanes that were capable of engaging with modern German designs over the Western Front and would instead have to rely on outfitting its Aero Squadrons with British and French fighters and reconnaissance aircraft. By March 1918, the United States Army Air Service put out a request for American aircraft manufacturers to develop a home-grown design for a fighter that was to be powered by the 300 hp (220 kW) Wright-Hispano H (Wright-Hisso) V8 engine, a licensed development of the Hispano-Suiza 8 water-cooled inline engine used to power the French SPAD XIII fighter flown by American aces Eddie Rickenbacker and Frank Luke.

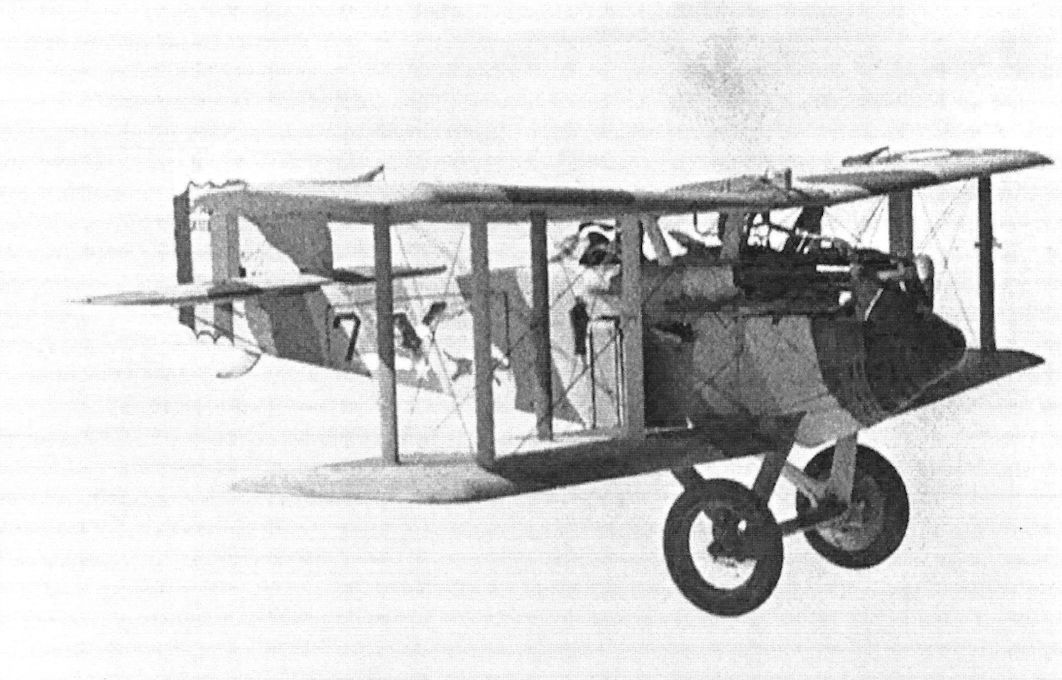

The most promising of these designs came from the Thomas-Morse Aircraft Corporation of Ithaca, New York, which had gained success with its S-4 Scout advanced trainer, which was designed by the English aircraft designer Benjamin Douglas Thomas, who had worked with Vickers and Sopwith before moving to work with the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company, having designed the Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” trainer. After two other designs, the MB-1 and MB-2, were rejected during the prototype stage, Thomas presented his plan for a single seat biplane with two sets of interplane struts similar to the SPAD XIII. The radiator was mounted in the center section of the upper wing, similar to the German Albatros fighters, and that same center section had a cutout for the pilot sitting in the cockpit, who also had two synchronized .30 caliber machine guns at his disposal. The US Army Air Service would place an order for four prototypes in September 1918.

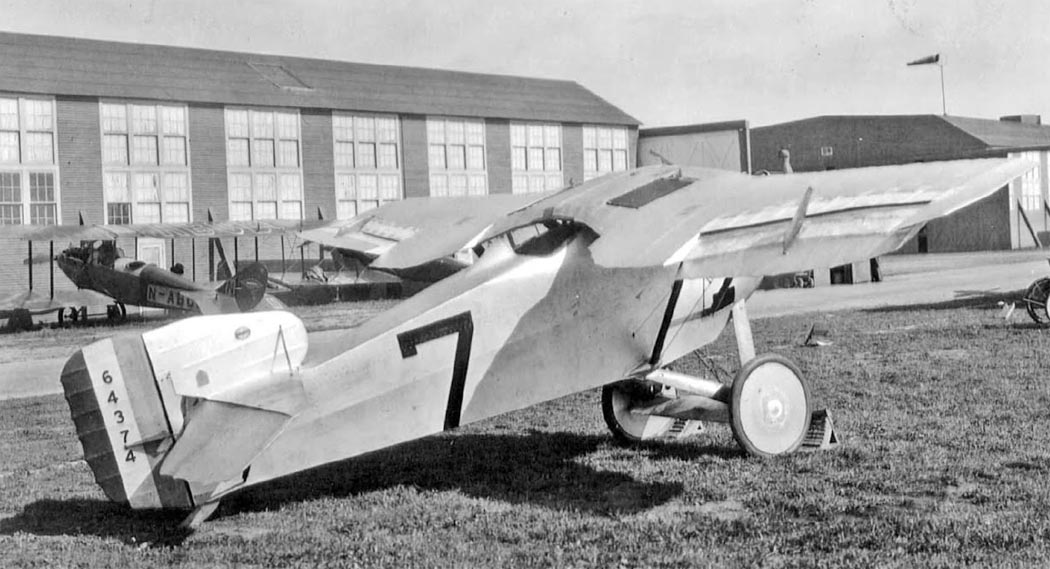

Although the First World War ended with an Armistice on November 11, 1918, and military budgets would soon be cut back, development of the Thomas-Morse MB-3 continued, as the United States needed a fighter of its own design for its own air defense. On February 21, 1919, the first prototype MB-3, Air Service serial number A.S.40092, made its first flight at Ithaca, NY, with Frank H. Burnside at the controls. Subsequent testing at McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio found the aircraft to have good overall performance, but poor pilot visibility. The aircraft also suffered further drawbacks in the form of fuel leak, engine vibration, and difficult access for mechanics. Nevertheless, the Army Air Service decided to accept the aircraft into service, ordering 50 more aircraft from Thomas-Morse in June 1920.

With the budgets of the US armed forces having shrunk back significantly immediately following the end of WWI, senior military and political officials were still unsure of the airplane’s potential in the military. The proponents of military aviation championed the entry of both stock military aircraft and purpose-built racing aircraft of the Army and Navy being flown in air races such as the Pulitzer Trophy, first held in 1920 at Mitchel Field on Long Island, New York. At the inaugural race, Canadian-born WWI flying ace Harold Evans Hartney won second place flying a MB-3 prototype with the race number 41, second only to the Verville-Packard R-1 racer flown by Corliss Champion Moseley. The success of the Thomas-Morse MB-3 led to the development of two dedicated racing aircraft based on the MB-3, the Thomas-Morse MB-6, which featured a shorter set of wings with a single set of interplane struts, and the MB-7, which had a single parasol wing, and was flown by the US Navy. Both models flew in the 1921 Pulitzer Race, held in Omaha, Nebraska, and one of the two MB-7s participated in the 1922 Race at Selfridge Field, Michigan.

At the same time the MB-3 was being used as an air racer, the USAAS placed an order for an additional 200 examples, but with revisions to the design such as a four bladed propeller over the original two bladed one, two fuselage mounted radiators, a revised tail and a stronger structure for the fuselage. While Thomas-Morse was confident that it was up to the task of modifying the MB-3 to the new MB-3A standard, the USAAS put the manufacture of the MB-3A up for bids from competing firms, and at least five other companies entered the competition to fulfill what was then the largest production for fighter aircraft US military aviation history. The winning bid, however, came from the Boeing Airplane Company of Seattle, Washington, who heavily underbid Thomas-Morse, and was awarded the contract on April 21, 1921. This contract would help Boeing become a more prominent company in the American aviation industry that would go to become arguably the world’s leading producer of airplanes. Despite losing the contract to build the MB-3A, the first operational MB-3s rolled out of the Thomas-Morse factory in April 1921, but when one of the aircraft lost a section of its upper wing during a diving test, the MB-3’s service entry was delayed in order to determine the cause of the incident.

By January 1922, the first MB-3s entered service with the 1st Pursuit Group based at Selfridge Field, and these new types flew alongside the group’s foreign-built SPAD XIIIs, Fokker D.VIIs, and American-built S.E.5as. Despite being reported on during the flight-testing phase, the MB-3s continued suffering from engine vibration issues, that were traced back to the design of the engine mounts. Between February and March of that year, the US Marine Corps received ten MB-3s built by Thomas-Morse. The Marines had originally ordered 12 aircraft, but the Navy revised the order for two of the aircraft to become the aforementioned MB-7 monoplane racers. The Marine aviators disliked their new aircraft, however, and by July of that year they sold their examples back to the Army, which used them as MB-3M advanced trainers.

As the Marines returned their MB-3s to the Army Air Service in July, the first of the new MB-3As entered service with the USAAS on July 21, 1922, with the final examples being received on December 27. The last 50 MB-3As featured another revised tail assembly and rudder, and several aircraft flew not only with two .30 caliber machine guns, but with either one .30 caliber and .50 caliber machine each or with two .50 machine guns. In addition to flying in the continental United States, the Thomas-Morse MB-3 was flown by American squadrons stationed in overseas American territories such as Hawaii, the Philippines, and the Panama Canal Zone.

By 1923, the MB-3 had become the most prominent American-designed fighter in service with the US Army Air Service. Yet its successors were already in development as well. That same year saw the introduction of the Boeing PW-9 (PW=Pursuit, Water-cooled) and the Curtiss PW-8 (later to become the Curtiss P-1 Hawk). Powered by new American-designed V-12 engines such as the Curtiss D-12 engine as opposed to the eight cylinder Wright-Hissos derived from the Hispano-Suiza 8, the new fighters quickly proved their worth, and by 1926, the Thomas-Morse MB-3s, along with the Boeing-produced MB-3As, were relegated to secondary duties such as becoming advanced single seat trainers for pursuit training, primarily flown in this role at Kelly Field in San Antonio, Texas, and the last examples remained in service until 1929. But although the MB-3 never fired a shot in anger, and soon faded into the history books, they would be immortalized on the silver screen with one of the biggest films of the Silent Era, Wings.

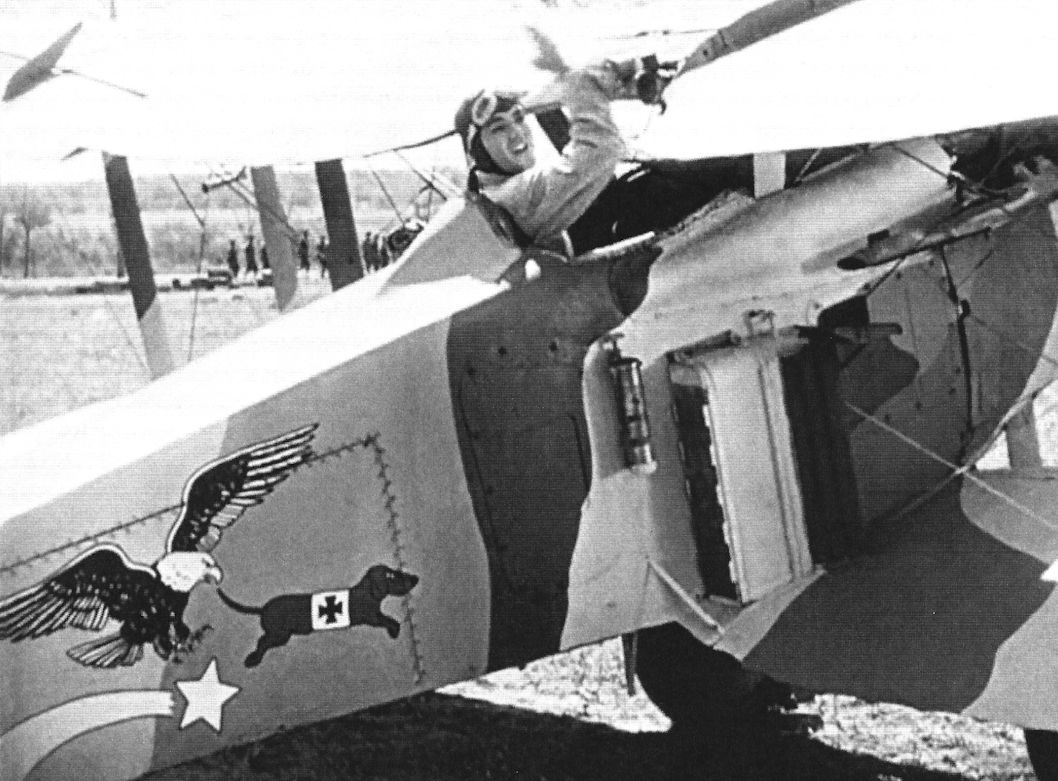

Produced by Paramount Pictures, Wings is a classic romantic war drama, with Charles “Buddy” Rogers and Richard Arlen portraying fighter pilots Jack Powell and David Armstrong as they compete for the affection of hometown sweetheart turned combat nurse Mary Preston, played by Clara Bow, one of the most prominent actresses of the Silent Film era. The director of the film was William A. Wellman, who had himself been a fighter pilot in WWI, serving in the French Air Service’s Escadrille Spa.87, earning the Croix de Guerre and the nickname “Wild Bill” for his exploits. He ended the war with three confirmed aerial victories and five probable victories before returning to the USA to serve as a flight instructor at Rockwell Field in San Diego, California.

Wellman used his first-hand knowledge to create stunning aerial sequences filmed in the skies above Kelly Field, Texas with Thomas-Morse MB-3s serving as stand-ins for French SPADs, and Curtiss P-1 Hawks for Fokker D.VIIs (though some MB-3s also flew in German colors for the film), while a Martin MB-2 bomber stood in for a German Gotha bomber during the film. The film was even more remarkable for the fact that Arlen and Rogers flew MB-3s and P-1 Hawks solo during the production, and they operated movie cameras mounted in front of their cockpits to film their acting from the air. This is even more stunning for the fact that although Richard Arlen had previously served as a pilot in Canada with the Royal Flying Corps during WWI, “Buddy” Rogers was taught to fly a plane and fly solo for the making of this film.

Wings became one of the highest grossing films of 1927, with Charles Lindbergh’s transatlantic flight that year drawing even more interest in seeing the film, which in 1929 became the first motion picture to win the Academy Award for Best Picture, as well as earning the Award for Best Engineering Effects. The film has since been selected for preservation in the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry and has entered the public domain in 2023. Today, there are no surviving examples of the Thomas-Morse MB-3, but its legacy remains important in the history of American military aviation, and in the history of aviation films.

Today in Aviation History is a series highlighting the achievements, innovations, and milestones that have shaped the skies. All the previous anniversaries are available HERE