By Ronan Thomas

2024 marks the 80th anniversary of iconic Second World War military offensives in Europe. 1944 saw RAF Bomber Command’s all-out operations against Nazi Germany, Monte Cassino in Italy (January to May 1944), D-Day, Caen and Normandy in northwestern France (June-August), Operation Market Garden in Holland (September) and the Battle of the Bulge in Belgium, Germany and Luxembourg (December 1944). 80 years on, these critical clashes are rightly the subject of current commemoration across Europe. The commitment and bravery of those who fought in them, from Britain, its Commonwealth, and Allies is truly humbling. For many of these young airmen, soldiers, and sailors, overseas military service was a searing experience, never forgotten. Their stories fill both relatives and historians with awe at their resilience and achievements. Yet in 1944 those fighting on the front lines in Europe were not alone in facing danger. In 1944 Britain on its home front faced an unprecedented menace. It marked all who endured it. Its baleful 80th anniversary is also now passing. The RAF played a critical role.

Blitz background

By early 1944, British civilians hoped that the mass bombing of their cities by Luftwaffe aircraft was over. During the Blitz (7 September 1940-10/11 May 1941), bombs rained down for eight months across Britain. In London, nearly 30,000 died and around 50,000 others were seriously injured. Devastating air raids also hit eighteen other British cities, ports and industrial production centres. Then Luftwaffe air raids largely ceased. Respite came as Hitler turned eastwards. By May 1941 the Nazi leader was finalising his grand strategic plan: the invasion and defeat of the Soviet Union. This invasion — Operation Barbarossa — was launched on 22 June 1941, diverting many German aircraft from attacks on Britain. Although Luftwaffe bombers continued to mount small raids on British targets, from mid-May 1941 to 21 January 1944 the number and intensity of attacks dropped off dramatically. The next two-and half-years became known as ‘The Lull.’ But air raids on Britain, and on London in particular, were far from over. In 1944 a new phase of arbitrary destruction from the air was unleashed, and the RAF stepped into the breach.

1944 attacks

From January to April 1944, substantial German air raids resumed in the so-called ‘Little Blitz.’ London and southeast England were singled out for attack in retaliation for Allied saturation bombing of major German cities, particularly Berlin. In a new conventional bombing offensive — Operation Steinbock — the Luftwaffe devoted 524 aircraft for further night raids on London, including Junkers JU-188, Dornier Do-217, Messerschmitt ME-410 and Heinkel HE-177 bombers. Around 460 aircraft from this force were airworthy. During four months of raids — fourteen on London and other probing attacks on Bristol, Hull and Cardiff — approximately 1,500 people were killed and almost 3,000 others seriously injured. In London, civilians flocked to newly-opened deep shelters. But the Luftwaffe bomber force was mauled and progressively depleted during the ‘Little Blitz.’ In four months, 329 aircraft were either lost or redeployed. Over 100 were lost to RAF interception, ground defensive fire, crew inexperience, and maintenance problems.

Directed by Air Chief Marshall Roderic Hill, radar-equipped RAF de Havilland Mosquito and Bristol Beaufighter night-fighters exacted an ever-increasing toll on the remaining German formations. Head of the Luftwaffe, Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering, also diverted squadrons to Italy after the allied landings at Anzio from 22 January 1944 and to support German occupation forces in Hungary from mid-March 1944. The final raid of the ‘Little Blitz’ took place on 18-19 April 1944. Thereafter, Goering devoted what was left of his bomber strength in France to preparations for the expected allied invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe. The ‘Little Blitz’ was over.

V-Weapons assault

Even as battered Britain glimpsed victory on the horizon, following the successful D-Day landings in Normandy on 6 June 1944 (Operation Overlord), a final vicious air assault began: the V-Weapons. In a highly destructive offensive, from 13 June 1944 to 29 March 1945, Hitler launched new ‘Vengeance Weapons’ (Vergeltungswaffen) against London. It was a campaign of retribution, in response to the ever more ruinous RAF and Allied saturation bombing of German cities (1940-1945). Over 3,000 V-weapons struck the capital and its suburbs. Almost 9,000 people were killed. At least 24,000 others were seriously injured.

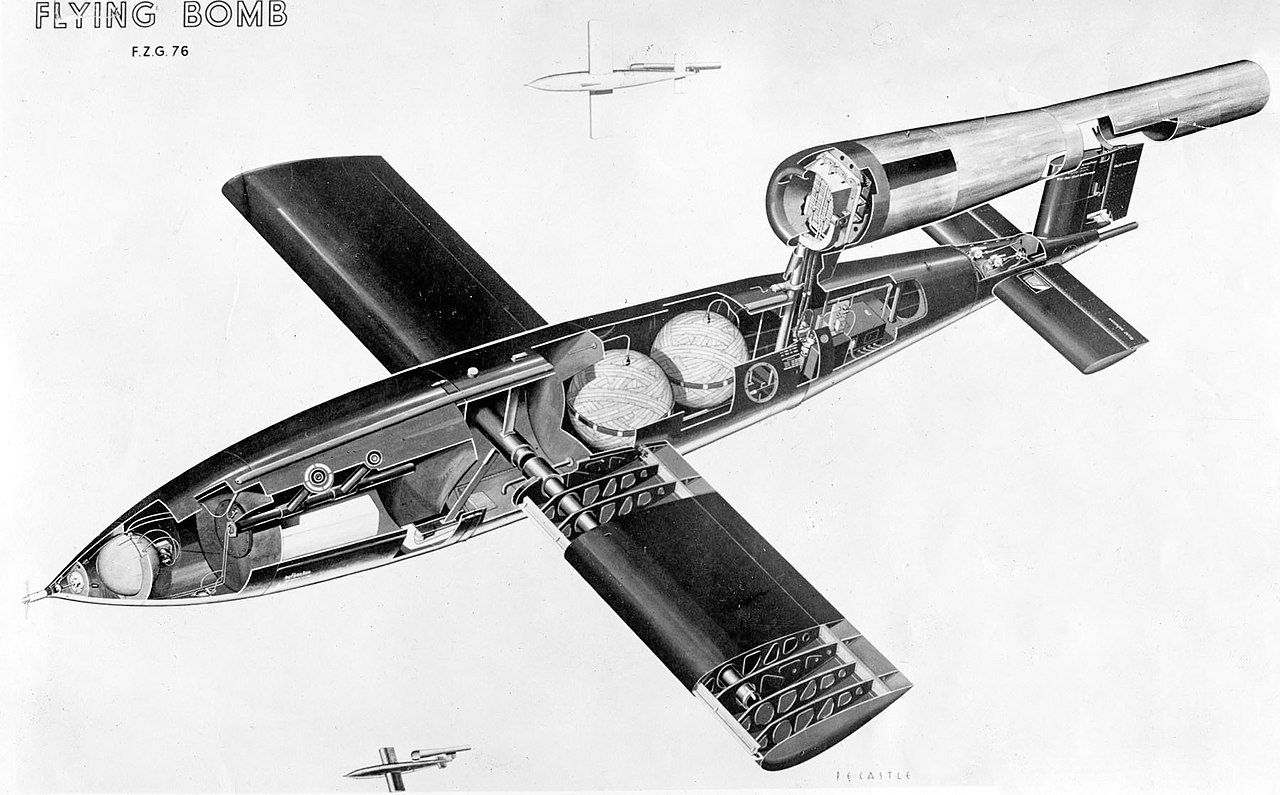

The first of these were the V1s (known to Londoners as ‘Doodlebugs’). The V1s were pilotless flying bombs with a range of 149 miles, powered by an Argus 109-014 pulse engine and launched by catapult from static ramps in occupied Europe. Design faults and RAF raids on their testing facilities at Peenemunde, on Germany’s Baltic coast (notably Operation Hydra, 17-18 August 1943) and on launch ramp sites in Northern France, delayed their use until June 1944. Each V1 was divided into five sections: pulse engine, control compartment, spherical compressed air tanks, alcohol fuel tank and nose warhead. Each flew at around 400 mph and were guided to their targets by autopilot and gyrocompass. After launch from northern France or Holland, V1s could reach London in 25 minutes. They arrived by day and by night. A small nose airscrew (air log) measured a set range: every V1 sent against the capital was calibrated for the exact distance to Tower Bridge, on the Thames. Once over London, the V1’s droning pulse engine cut out and it dived down, silently and menacingly, to detonate on the city. Each V1 delivered a powerful warhead: 1,870 lb (850kg) of high explosive.

The RAF responds

Responding to this unprecedented threat, the RAF conducted Mk IX Supermarine Spitfire photo reconnaissance flights to identify the V-weapons infrastructure (Operation Crossbow), alongside USAAF (United States Army Air Force) bombing raids. At RAF Medmenham, Buckinghamshire, photographic intrepreters (PIs) used stereoscopic (3d) glasses to identify likely V-weapons sites. RAF PR-IX, PR-X and PR-XI variant Spitfires then flew sorties at 30,000 feet, before diving down to low level and taking pictures. They identified some 90 launch ramps. These were supplemented by a British military intelligence campaign of misinformation — directed by PM Winston Churchill’s Assistant Director of Intelligence, Dr R.V.Jones — as to where the V1s were actually striking London. But until their launch ramps were overrun by the advancing allied armies, V1s badly damaged the capital. The first V1 fell on 13 June 1944 on Bow, East London (6 killed). The public were first informed about the dangers from flying bombs on 16 June. Of over 10,000 V1s launched, approximately 9,251 were fired against London in an eighty-day campaign. 7,488 crossed the south coast of England. 3,957 were shot down by anti-aircraft fire, by RAF fighter interception — by Hawker Tempests, Spitfires, de Havilland Mosquitos and by Britain’s first jet fighter, the 400mph Gloster Meteor — or hit the cables of barrage balloons tethered outside the capital. Famously, RAF fighters bravely pursued the V1s on their approach to London. Opening fire on V1s was hazardous, to put it mildly. The pilots had to judge the exact distance to avoid the resulting huge mid-air explosion. To bring the doodlebugs down, some pilots also caught up alongside and just below, tilting their wing tips at close separation to disrupt the flying bombs’ air flow, causing them to fall off course.

Around 2,500 V1s actually hit London (a rate of of 50 to 100 per day in late June 1944). 6,184 people were killed and an estimated 17,981 injured. 18,000 homes in London (400 per V1) were destroyed by flying bombs and 137,000 others damaged. In the final stages of the campaign, V1s were also air-launched against Britain by Heinkel HE-111 bombers. The last V1 to hit Britain landed near Datchworth, Hertfordshire on 29 March 1945 (none killed or injured). At the time, V1s were widely feared across London. Their numbers seemed inexhaustible. In London, two of the worst incidents of the war took place in Westminster in June 1944, at Aldwych (46 killed) and at the Guards Chapel, Wellington Barracks (121 killed attending a morning service, including 63 soldiers). Elsewhere in London, more evidence of the horrendous detructive power of V1s came on 28 July 1944, when one hit Lewisham (killing 51 and injuring 151).

V1s were just the beginning. From 8 September 1944 to 28 March 1945, an even more advanced V-Weapon was deployed against London: the V2. The world’s first ballistic missile, the V2 Long Range Rocket carried a one ton high explosive warhead and was fired from mobile launchers in Germany and from the occupied Low Countries. The 14-ton, 47ft high V2s — built by slave labourers at underground sites in Germany and Poland — were powered by a revolutionary alcohol/liquid oxygen rocket engine, had a range of 225 miles and flew at supersonic speed (3,600mph). V2s reached a height of around 50 miles in the upper atmosphere, before descending to their target. They were guided by their own on-board gyroscope systems and by four external rudders on their tail fins. The first V2 was launched from Holland against Paris on 8 September 1944. In London, no defensive response to the V2 was possible. RAF radar operators picked them up on their screens — for a 50 second window after launch — but their speed presaged the missile warfare of the future. After launch from occupied Holland or Germany, V2s could hit the capital in five minutes. Londoners did not hear them coming. There was no time to take cover.

The first V2 to hit London fell on Chiswick, west London, on 8 Spetember 1944 (killing 3 and injuring 22). Local residents were told it was a gas main explosion, before the more disturbing truth emerged. Thereafter, the majority of V2 rockets landed in the capital’s East End, across south east London and in Essex and Kent. In Westminster one V2 struck close to Selfridges Department Store on Oxford Street (6 December 1944, 18 killed, 39 injured). Another fell into the River Thames, east of Waterloo Bridge. A fouth exploded at high altitude over Victoria on 12 November 1944.

In all, 1,054 V2s hit England (an average of five per day). 517 (an average of three per day) reached London. 2,754 people were killed with 6,523 seriously injured. Each V2 damaged an average of 600-700 properties in its blast radius, an extraordinarily high number. One of the worst V2 incidents took place at New Cross in South London on 25 November 1944 (168 killed). V2 targetting effectiveness was partially reduced by ongoing intelligence disinformation by Dr R.V. Jones and his team. The last V2 launched against Britain hit Orpington, Kent on 27 March 1945 (1 killed). At war’s end the V-weapons story did not end. The German head scientist of the V2 programme, Werner Von Braun, surrendered to allied forces in 1945 and was recruited to assist the United States’ own Cold War ballistic missile programme. In due course, Von Braun helped design and produce NASA’s Saturn V rocket, which took American astronauts to the Moon in the Apollo missions of 1969-72.

Today, exactly 80 years on from the tumultuous military events of 1944, the RAF’s critical role in the successful defence of London deserves fresh recognition. In 1944, it courageously mauled the Luftwaffe’s bombing and V-weapons assault, ensuring that V was for Victory, not Vengeance.

Good overview presented there Emma, ta.

If I might add a few cogent points – the V1 was the 1st effective cruise missile, and in many aspects, this Luftwaffe program was more successful than the Army/SS V2 ballistic missile, from the basic cost per unit, through the considerable defensive efforts expended by the Allies, plus the pervasive psychological aspects of dread – caused by V1s as seen/heard on approach (even General Eisenhower noted this), and the serious blast damage due to its shallow impact strikes.

Interestingly, the V1 was quickly analysed, cloned and put into mass-production – by Ford for US Forces as the ‘Loon’ – with intent for use as a cost-effective bombardment weapon against Japan.

While Mustangs (the sole US ‘Lend-Lease’ type used by the British – which were fast enough to intercept V1s at low altitude) also contributed, their ‘light’ armament of four 0.5in ’50 cal’ machine guns was a limitation, so it was the recent service introduction of the high-performance Hawker Tempest, with its four 20mm cannon and early HUD (gunsight graticule reflected directly on to the armour-glass panel) and powerful Napier Sabre engine – allowing a steady run in for accurate shooting – which even though equipping only a few units, duly downed ~800 V1s, this being about 40% of the RAF’s total effort.

Other major innovations were also introduced, the ‘proximity fuse’ which made

anti-aircraft shellfire much more effective, and led to the early development of air-to-air missiles, due to a Typhoon fighter-bomber letting loose its air-to-ground rockets at a V1 in flight, & knocking it down – which prompted trialling rockets with proximity fuses – as a weapon with future potential.

Curiously, this campaign of using cheap ‘flying bombs’ to ‘terrorise’ civilian

population centres, requiring costly defensive measures in response, is happening 80 years later, too.