By Chris Bucholtz

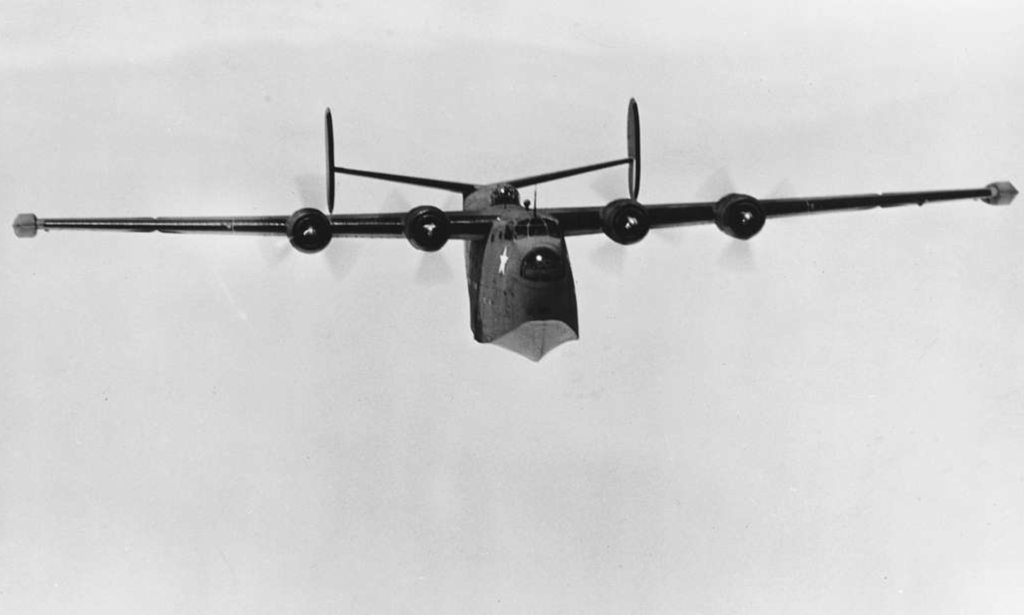

The Consolidated PB2Y Coronado entered U.S. Navy service after a protracted five-year development, and its reputation suffered because of it. Little did its detractors know that the big four-engined flying boat would succeed in one of the most unlikely missions of the Pacific War — a series of 2,400-mile round trip raids on heavily-defended Wake Island.

When the Navy issued its contract for the Coronado prototype, it was the most complex plane it had ever ordered. A short 18 months later, on August 13, 1937, the XPB2Y-1 took to the skies for the first time, revealing plenty of room for improvement — lateral instability was a major problem for the deep-hulled boat, so the single tail fin was augmented by two smaller fins on the horizontal stabilizers. This didn’t correct the problem sufficiently, so the tail was completely revised, giving the horizontals dihedral and capping each with a large oval fin and rudder arrangement much like that of its Consolidated stablemate, the B-24 Liberator. The hull was also redesigned to improve hydrodynamic performance. These fixes coincided with a 15-month period between 1937 and 1939 when the Navy had no funds to purchase the planes. Finally, on March 31, 1939, the Navy issued a production order for six PB2Y-2s, which entered fleet service on the last day of 1940.

Every new aircraft has kinks that must be worked out, but the Coronado showed off its kinks at the wrong time, according to Frank DeLorenzo, Naval Aviator Number 6449 and a Coronado command pilot who flew the boat through the entirety of World War II. Early in the plane’s service, it was tasked with transporting Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox to Pearl Harbor. “At that time, Patrol Squadron 13 (VP-13) only had four PB2Y-2s and none of them had self sealing gas tanks,” DeLorenzo said. “In topping off the plane designated to carry the SecNav, several fuel leaks were observed coming from the rivets in the bottom of both wings. Several attempts to cure the problem were attempted and different planes were used. This caused a 24-hour delay in getting SecNav into the air and on his way to Pearl Harbor. It also cast a black cloud over the reputation of the Coronado among ranking people in Washington! In my opinion the Coronado never completely recovered from this unfortunate event.”

On Christmas Eve, 1941, DeLorenzo was one of the pilots who flew Adm. Chester Nimitz from San Diego to Pearl Harbor, arriving on Christmas morning so that Nimitz could take command of the Pacific Fleet. DeLorenzo had been flying patrol missions from his base in San Diego; seeing the wreckage of the Pacific Fleet made him long for a chance to take the war to the Japanese.

By this time, the Navy had ordered the PB2Y-3, which featured self-sealing fuel tanks, additional armament, and increased armor in addition to an improved version of the Pratt & Whitney R-1830 engine. “The Coronado was not really mechanically ‘difficult,:’ said DeLorenzo. “It had good, reliable engines with electric props, of which the inboard props could be reversed for fantastically easy maneuvering on the water.”

As part of VP-13, DeLorenzo’s next two years were a mix of patrol missions and frequent long-range cargo and VIP passenger flights — no other Navy aircraft could match the combination of its 2,370-mile range, 140mph cruising speed (15mph faster than the PBY Catalina) and passenger comfort.

In late January 1944, after two years of long, important but relatively sedate flights, DeLorenzo and his squadron mates in VP-13 received electrifying news: along with sister squadron VP-102, they would strike occupied Wake Island in a series of bombing missions that would employ the range and enormous payload of the Coronado — the first time the Coronado had been used as a bomber. “We had flown so many patrols looking for enemy subs, aircraft and ships with practically no positive results that the promise of a positive engagement with them was a tremendous boost in our morale!” said DeLorenzo.

Wake Island, in Japanese hands since Dec. 23, 1941, could potentially serve as a base for aircraft to detect and attack Allied shipping headed to landings at Kwajalein and Majuro in the Marshall Islands, 700 miles to the north. While Wake had been subject to raids from American carriers and B-24s flying from Midway, planners wanted the Japanese occupied night and day. The landings on Kwajalein were scheduled for Jan. 31; the first of VP-13’s missions would take place on Jan. 30.

The Coronados flew from Hawaii to Midway on Jan. 29. “The Midway personnel were very accommodating,” wrote VP-13’s Bill Kitchen. “I’ll never forget the box lunch they fixed for us on the first mission. We took off around five o’clock. Once our heading was set and engines leaned out to maximum, we settled down to eat. Of all the many in-flight meals that I had during and after the war, none compared with this one. I really think they looked at it as our last supper. We had stuffed celery with cheese and pickles, frosting on our cupcakes, and the best part was the curly paper they wrapped around the bone on the fried chicken leg. Wow!” Kitchen was also unaccustomed to being issued a flak vest. “When I heard we were in the first wave of six planes going down the runway at 200 feet, I elected to sit on mine,” he said.

“VP-13 was assigned the low-level attack with 12 planes, and VP-102 was assigned the high-level attack about 25 minutes later,” DeLorenzo recalled. “The low-level attack went in very, very low to avoid radar detection and gain the element of surprise. The low-level group did an outstanding job of navigating and finding the island without the use of their radar, which could have cancelled the element of surprise by alerting Japanese electronic devices.”

The low-level group was led by LCDR Tom Connolly, who would years later play a key role in the development of the F-14, which was named in part after him. After the 8 1/2 hour, 1,182-mile flight from Midway, Connolly led the first six planes down the runway at Wake in a stepped-up V-formation. Chet Smith, who had learned to fly the Coronado as co-pilot to DeLorenzo, said his altimeter over the target indicated less 50 feet. Over the runway, the planes’ gunners opened fire and each Coronado dumped 8,500 pounds of time-delayed bombs on the airfield, then turned for home.

“I remember looking up through our escape hatch above the pilot’s seat and noticing we were so low that we were flying under their searchlight beams,” said Kitchen. Smith asked the bow gunner how much return fire was coming their way. “Very little,” the gunner reported. The waist hatch observer then said “moderate fire.” The tail gunner then announced “all hell broke loose!” “I guess we surprised them!” Smith said.

DeLorenzo was flying with VP-102 in the high-level group. “We made our run at about 8,000 feet. We had the advantage of an almost-full moon downrange of the island, which gave us an additional distinct visual advantage as well.”

When the intelligence officers briefed the crews on what enemy opposition they might encounter, “they told us that the Japanese anti-aircraft fire directors were based on a ‘sound detection’ principle and could home in on the harmonics of our propeller synchronizations,” said DeLorenzo. “Being in my 20s, with an abundance of curiosity and imperviousness, I decided to not desynchronize my props! What a mistake! I was met with much, much more severe anti-aircraft fire than the other planes were getting! With a hand motion faster than the eye could see, I quickly de-synched my props! I also related this action to the intelligence debriefing officers when we got back to Midway Island so that they could affirm the accuracy of their pre-mission briefing.. On the final approach to the target, I turned over control of the plane to the bombardier by means of the auto synchronization of the autopilot and the Norden bombsight. This meant on the final approach to the target the bombardier was flying the plane through the bombsight.”

The island’s defenders by now were alert and looking for payback. “We were taking a lot of anti-aircraft fire,” said DeLorenzo. “The rest of the crew felt helpless and very, very vulnerable! The fire was close (or so it seemed to me and the rest of the crew) but there were no hits. As soon as Sam Moskowitz, my bombardier announced through the intercom “bombs away!” I disengaged the autopilot and took evasive action. My lookouts reported no enemy aircraft, which was another relief to us. Mission accomplished!”

A U.S. submarine was stationed about 10 miles off of Wake as a “lifeguard” ship in the event an aircraft sustained damage severe enough to prevent it making its way back to Midway. Although it wasn’t needed on any of the four raids, “this, indeed, was a confidence and morale builder!” DeLorenzo said.

On the first raid, one of the planes in the high-altitude group was equipped with flash bombs and a light-sensitive camera to record the damage inflicted by the Coronados. On successive raids, other aircraft were also equipped with cameras and recorded damage from not only their drops but the damage from bomb drops of previous missions. The Coronados wrecked the airfield and destroyed hangars, aircraft, barracks, mess halls, fuel dumps, and communication equipment, as well as the motor torpedo boats Guroaitei No. 5 and Guroaitei No. 6.

The Jan. 30 raid was followed by missions on Feb. 4, 8 and 9. Although some aircraft suffered small arms hits on the first night, no PB4Y-3s were hit. “We all felt good about giving the Japs a bloody nose, even if it was on relatively isolated Wake Island!” said DeLorenzo. “Wake Island was pretty much isolated after these attacks and replenishment by the Japanese was very difficult and very rare.”

And, just like that, the Coronado’s time as a bomber was over. The planes returned to their patrol and transport duties. The planes did see combat, however. “When we had certain islands in our patrol sectors like Kwajalein, Eniwetok, Saipan, or Ponape, we could elect to strafe shore facilities. If conditions (weather, enemy fire, target opportunities, etc.) were right, we could strafe at will, but we were impressed with the fact that our primary mission was to search a certain sector for enemy forces or activities and we were not to play hero or daredevil to assuage our own ambitions,” DeLorenzo said. “Machine gun fire – you could definitely hear the firing, even from the cockpit and over the noise of all four engines. However, due to other noises generated by the slipstream, engines and being inside of a ‘tin can,’ the gunfire noise in the cockpit area wasn’t too disturbing.”

A number of small Japanese merchant ships were attacked and hit in the closing months of the war, and VP-13 gunners accounted for a G4M “Betty,” an H6K “Mavis” and an E13A1 “Jake” in air-to-air combat. But, with the war drawing to a close and the Martin PBM Mariner growing in numbers in the fleet, the end for the Coronado was in sight. “I recall flying the last of my squadrons ‘2Ys from San Diego to Alameda where they were turned over to an activity which cannibalized useable or sale-able pieces and components and they turned the rest of the carcass over to an outfit that melted down the steel and aluminum for scrap,” DeLorenzo said. It made him “Sad and nostalgic – but realistic! The flying boat carried a lot of its disadvantages with it – launching and recovering operations, the necessity of special beaching gear when it went to strange or distant destinations, hull vulnerability to submerged objects and coral heads, and the need for beaching crews to assist in bringing it ashore. But let’s not forget its big advantage! It could operate in strange and foreign places without the need of land-based runways.”

![Pappy Boyington Recounts a Dogfight In a WWII Radio Interview [Real Audio]. 14 Pappy Boyington](https://vintageaviationnews.com/wp-content/uploads/Pappy-Boyington-150x150.jpg)