As regular readers will remember, at time of writing, AirCorps Aviation was in the final stages of completing the magnificent restoration of a rare, razorback Republic P-47D Thunderbolt for the Dakota Territory Air Museum. The fighter is one of several, world-class efforts which the now-famed restoration shop in Bemidji, Minnesota has rolled out of its doors over the past decade or so. Not an organization to rest on its laurels, AirCorps is already working hard on a number of other projects, one of which they began in mid-2021 for the Wings of the North Air Museum in Eden Prairie, Minnesota. This latest project is based around the wreck of a rare, early-model Mustang, P-51B 42-106602, nicknamed Shillelagh, which has an extensive combat history. Two of those who flew the Mustang also have interesting histories: David O’Hara, Shillelagh’s regular pilot (who also named her) and Kenneth H. Dahlberg, the triple-ace and former Prisoner Of War who was at the controls on the fighter’s final mission. As already noted, Shillelagh’s rebuild began in earnest at AirCorps Aviation during 2021, and much has taken place in the interim. So without further ado, here is Chuck Cravens’ third report on Shillelagh…

Update

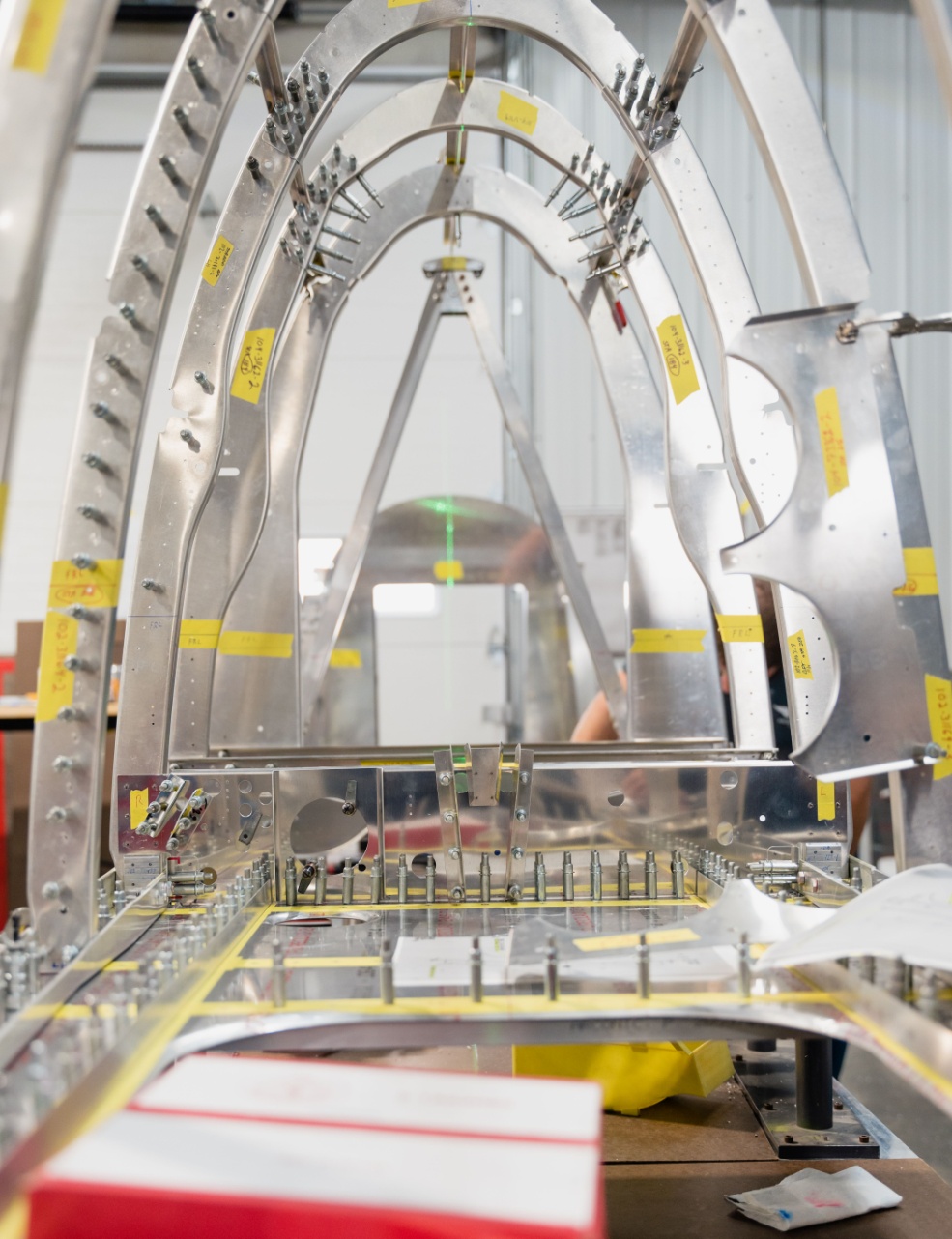

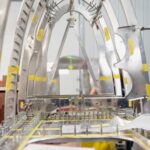

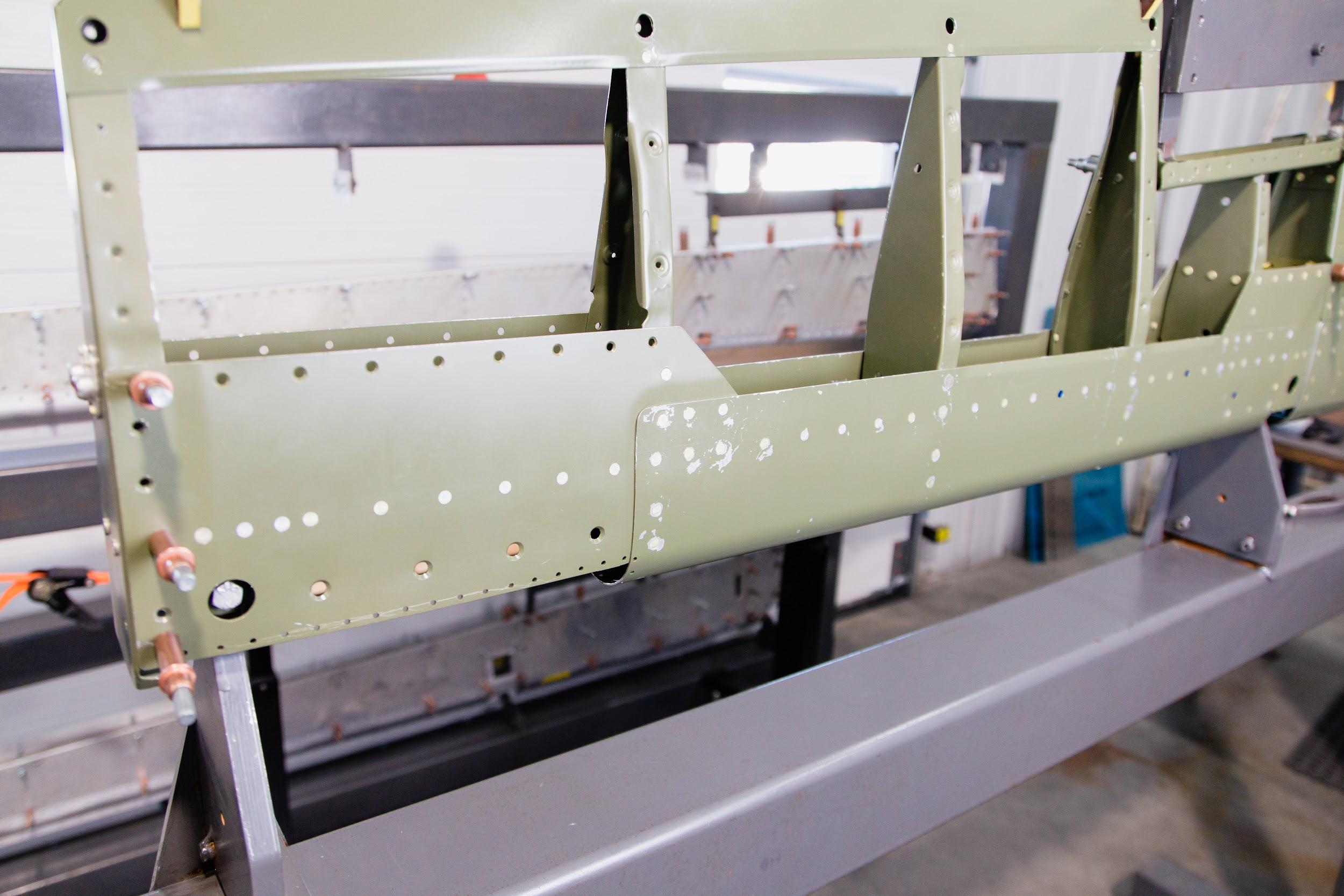

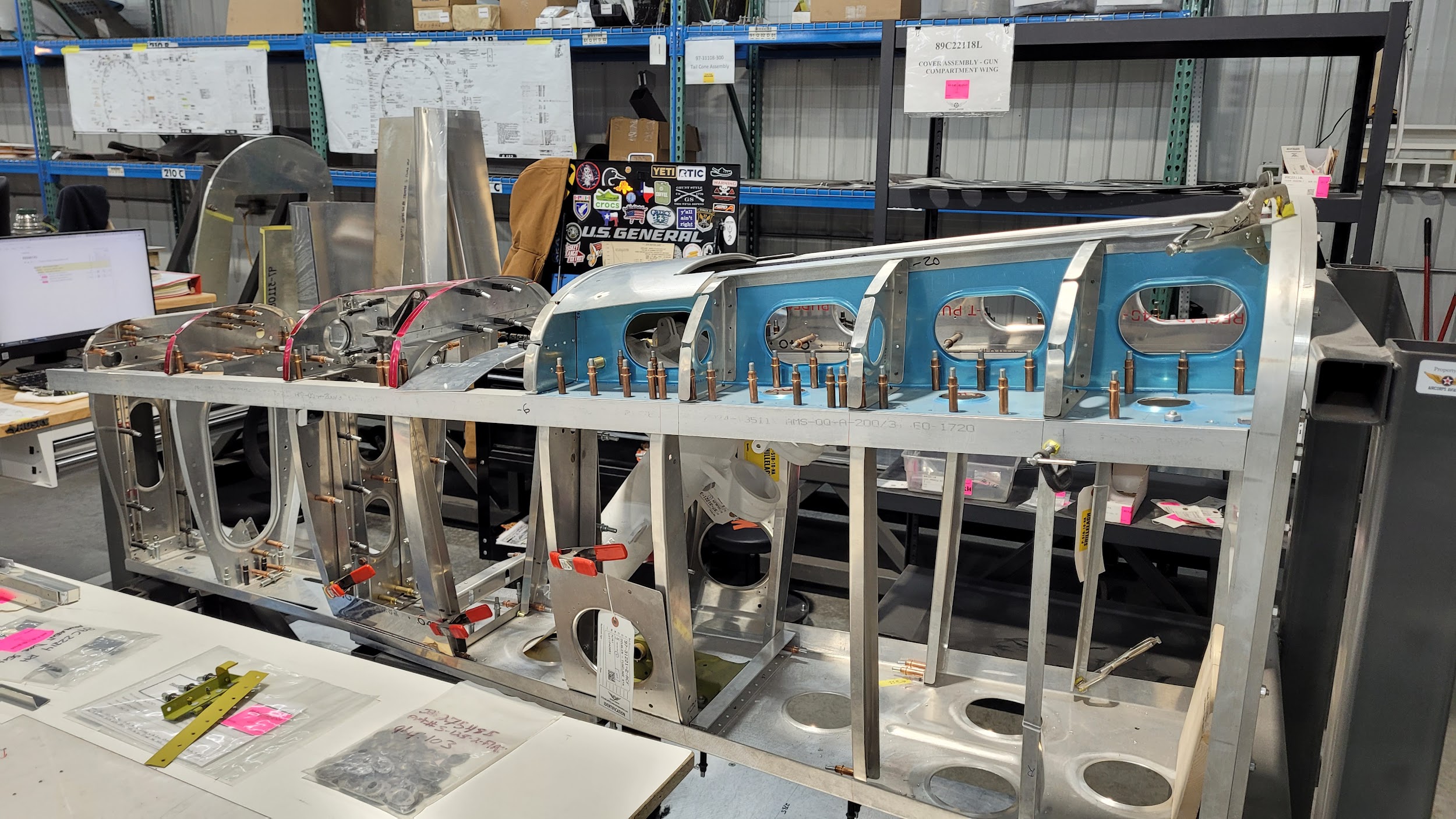

Fuselage Structure

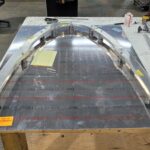

Ailerons and Elevators

While the fuselage underwent assembly, parallel work took place for the ailerons and elevators.

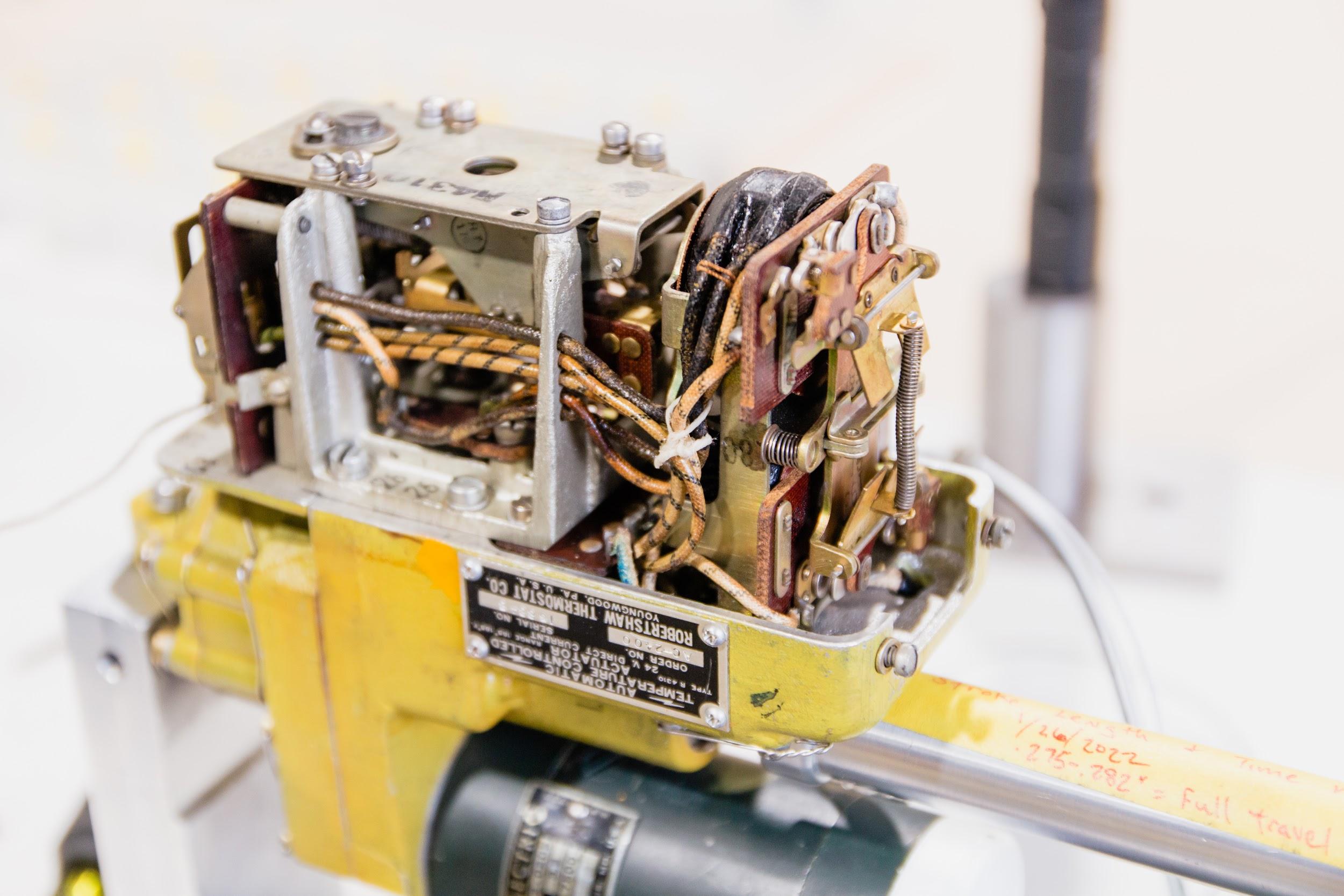

Robertshaw Actuator

Tail Cone

The P-51B’s tail cone was the first of three major fuselage sections to undergo assembly. While much of this structure is newly fabricated, all of its castings are of original wartime manufacture.

Mustang History

The Mustang’s story is well documented. For a comprehensive account of the B model’s development, I highly recommend a fine book by James Marshall and Lowell Ford: P-51B Mustang, North American’s Bastard Stepchild that Saved the Eight Air Force.

To summarize the Mustang’s origins, however, the type owes the impetus behind its design and manufacture to the British Purchasing Commission (BPC). Established in New York City during 1938, the BPC sought US aircraft manufacturing capacity to supplement what was available in the UK, since domestic factories were struggling to keep up with the needed production rates and also under constant threat of destruction from German bombing raids. Britain’s Royal Air Force (RAF) were impressed with North American Aviation’s rugged AT-6 Texan (the Harvard in UK parlance) so, in late 1939, the BPC approached the company, hoping to arrange a contract to build Curtiss P-40s under license, since that design was the only available American fighter type then capable of competing with British adversaries in the skies over Europe.

However, the engineers at North American Aviation (NAA) felt that they could build a better fighter, and in less time than it would take to set up a P-40 production line of their own. By April of 1940, after much discussions back and forth with the British regarding the aircraft’s specifications, North American Aviation’s chief designer, J.H. “Dutch” Kindelberger, presented its design proposal for the new fighter, the NA-73. The BPC quickly reached a verbal agreement to purchase some 300 examples of the new fighter. Soon after, the Anglo-French Purchasing Board (as the British Purchasing Commission became known for a time) formally approved a purchase agreement with NAA for 300 fighters to be delivered to the British by January 1, 1941. The French agreed to purchase an additional 40 examples for their own air force. The prototype NA-73 first flew on October 26th, 1940. Named as the Mustang by the British, this new fighter began combat operations with the RAF in April, 1942.

The Mustang Mk.I, the RAF’s first variant, used an Allison V-1710 (typically a V-1710-39 or -81) as its powerplant. Unfortunately, these engines only had a single-stage supercharger, which limited their performance (significantly) above 15,000 feet. Even so, the often maligned Allison-powered Mustangs (Mustangs Mk.I and Mk.II, P-51, A-36, and P-51A) were actually effective fighters lower down – one must remember that the design was not primarily intended for bomber escort missions. Indeed, the British found them to be excellent ground support and long-range reconnaissance platforms.

Interestly, when flying below 15,000 feet, Allison-powered Mustangs were faster than the early mark Spitfires then in use and, perhaps more importantly, Mustang Mk.Is could carry twice as much fuel. This capacity, combined with the Mustang’s aerodynamically efficient airframe, offered the type far greater range than British fighters then in service. Britain used Allison-powered Mustangs in European combat throughout WWII, which proves that the variant made a significant contribution.

Even so, since the V-1710’s single-stage supercharger severely limited performance above 15,000 feet, any Allison-powered Mustang was clearly unfit to escort most heavy bomber escort missions, since those sorties typically took place at much higher altitudes. Pre-war thinking surmised that bombers could defend themselves without any need for escort fighters on daylight raids, but the staggering losses which both the RAF and USAAF incurred on many such missions during their early experiences in WWII clearly revealed the fallacy of such a philosophy.

War planners came to recognize the need for a long-range fighter which could protect bombers over an entire mission. In mid-1942, a senior test pilot with Rolls-Royce named Ronald Harker postulated that a Mustang re-engined with a Rolls-Royce Merlin 61, with its two-stage supercharger, might enable the fighter to fulfill the need for a long-range bomber escort. Harker came to this conclusion after flying an Allison-powered Mustang I on April 30, 1942. His report to Rolls-Royce management closed with the following comment: “The point which strikes me is that with a powerful and good engine like the Merlin 61, its performance should be outstanding as it is approximately 35 mph faster than the Spitfire V with roughly the same power.”1

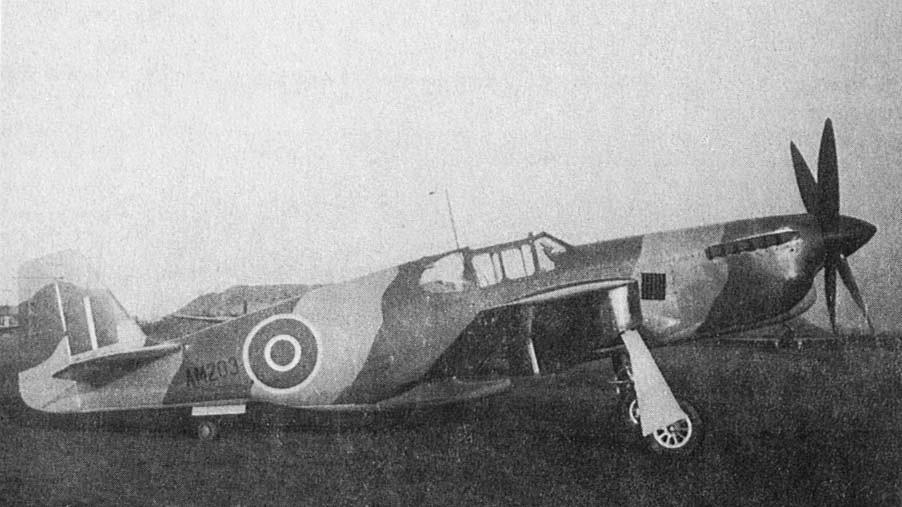

As a result, the RAF worked with Rolls-Royce to modify a Mustang Mk.I with a Merlin 65 powerplant in place of the V-1710; this hybrid airframe received the designation Mustang Mk.X.

1 James Marshall and Lowell Ford: P-51B Mustang, North American’s Bastard Stepchild that Saved the Eight Air Force, Osprey Publishing, New York City, NY, 2020, p.134.

The Mustang X first flew on October 13, 1942; the re-engined fighter’s performance, especially at high altitude, was spectacular. Its extraordinary high altitude performance, combined with its enormous range range, should have pushed the U.S. Army Air Forces to rapidly ramp up its development and introduction as an escort fighter capable of escorting daylight bombing missions all of the way to and from even the most distant targets. For some reason, however, Merlin-powered Mustangs were not available for this task until December, 1943!

Perhaps this lack of interest by the U.S. Army Air Forces (USAAF) may have been prejudiced by their original opinion of the Allison-powered Mustangs. It’s hard to say, but USAAF senior staff did at least begin warming to the type following positive reports from the RAF about its performance in low-altitude combat. As a result, they requisitioned several Mustang Mk.Ia airframes from the production line for use in attack and reconnaissance roles. These Mustangs came equipped with four 20mm cannon in the wings. At about the same time, the USAAF and North American sought priority for the very first V1650-3, a Packard-built variant of Rolls-Royce’s Merlin 61, for test purposes.

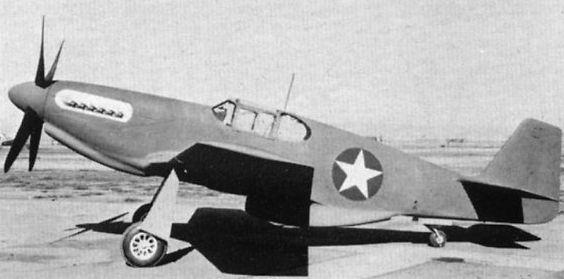

In early July of 1942, USAAF Material Command and North American Aviation reached an agreement to modify two P-51 (NA-91) airframes, 41-37352 and 41-37421, to accept V-1650-3 powerplants. Interestingly, the Army initially designated their first Merlin-powered Mustang variants as XP-78s, however this changed to XP-51B by the time of the variant’s first flight on November 30, 1942 (about 6 weeks after the Mustang X). The performance gains at higher altitude were remarkable; the XP-51B flew 100 mph faster than its Allison-powered brethren at 30,000 feet!

The first production P-51B rolled off the assembly line and flew in May, 1943. The USAAF initially ordered 400 examples while Britain requested more than 1,000.

Demand was so strong that North American Aviation chose to open a second production line at its factory in Dallas, Texas. These Dallas-built variants were designated as P-51Cs, although they were essentially identical to the P-51Bs from North American’s factory in Inglewood, California.

In the next update, we will examine the early combat introduction for the Merlin-powered Mustangs.

And that is all for the third edition of Chuck Cravens’ coverage describing the restoration of Wings of the North Air Museum’s P-51B Mustang Shillelagh at AirCorps Aviation. We will publish the next installment as soon as it becomes available! Many thanks to Chuck Cravens and especially to AirCorps Aviation for their continued, long-standing support!