On this day in aviation history, February 23, 1934, the Lockheed Model 10 Electra made its first flight. Developed as an all-metal light airliner, the Model 10 Electra was widely used around the world in various civil and military purposes carrying everything from freight to high profile civilian and military officials. Today, while the aircraft is treasured for its rarity and for the linage of multi-engine transports that were derived from the Model 10’s original design.

On this day in aviation history, February 23, 1934, the Lockheed Model 10 Electra made its first flight. Developed as an all-metal light airliner, the Model 10 Electra was widely used around the world in various civil and military purposes carrying everything from freight to high profile civilian and military officials. Today, while the aircraft is treasured for its rarity and for the linage of multi-engine transports that were derived from the Model 10’s original design.

By the start of the 1930s, the Lockheed Corporation of Burbank, California had gained a reputation for the reliability of its single engine monoplanes such as the Vega and the Model 9 Orion that were used by burgeoning airline companies as passenger or mail-carrying aircraft, or on record-setting flights by such figures as Roscoe Turner, Wiley Post, Charles Lindbergh, Jimmy Doolittle, and Amelia Earhart. Yet with these aircraft being constructed largely of wood (save for some Vega, Sirius and Altair aircraft being constructed with aluminum fuselages manufactured by the Detroit Aircraft Corporation), Lockheed realized that if it wanted to stay at the forefront of the aviation industry, it would have to adapt to building all-metal multi-engine aircraft.

The Kelly Effect

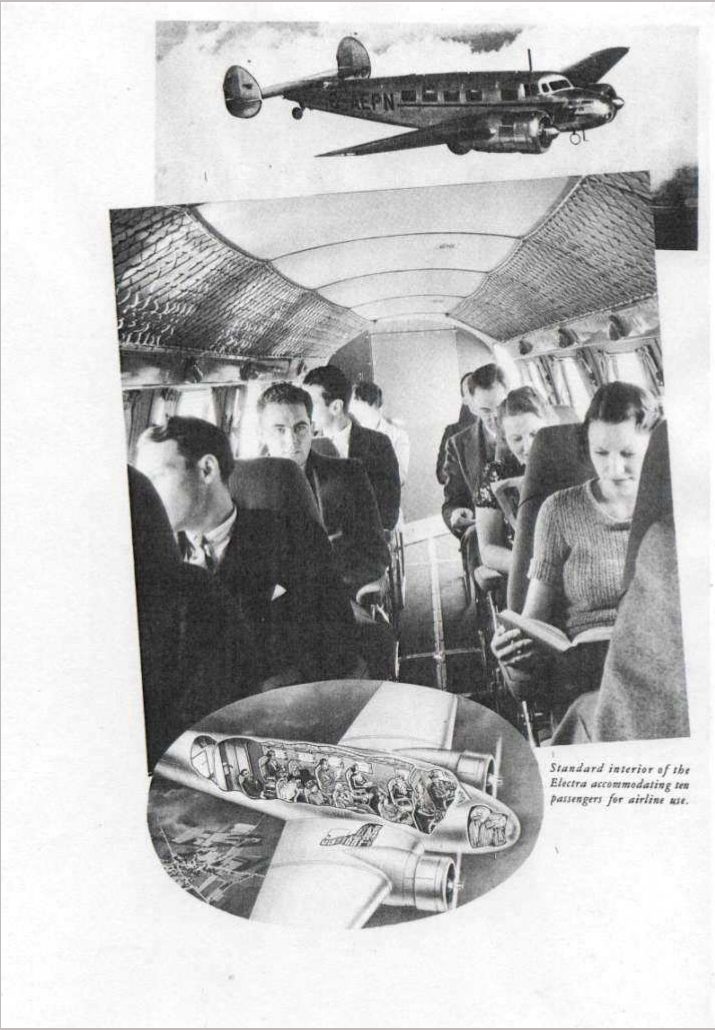

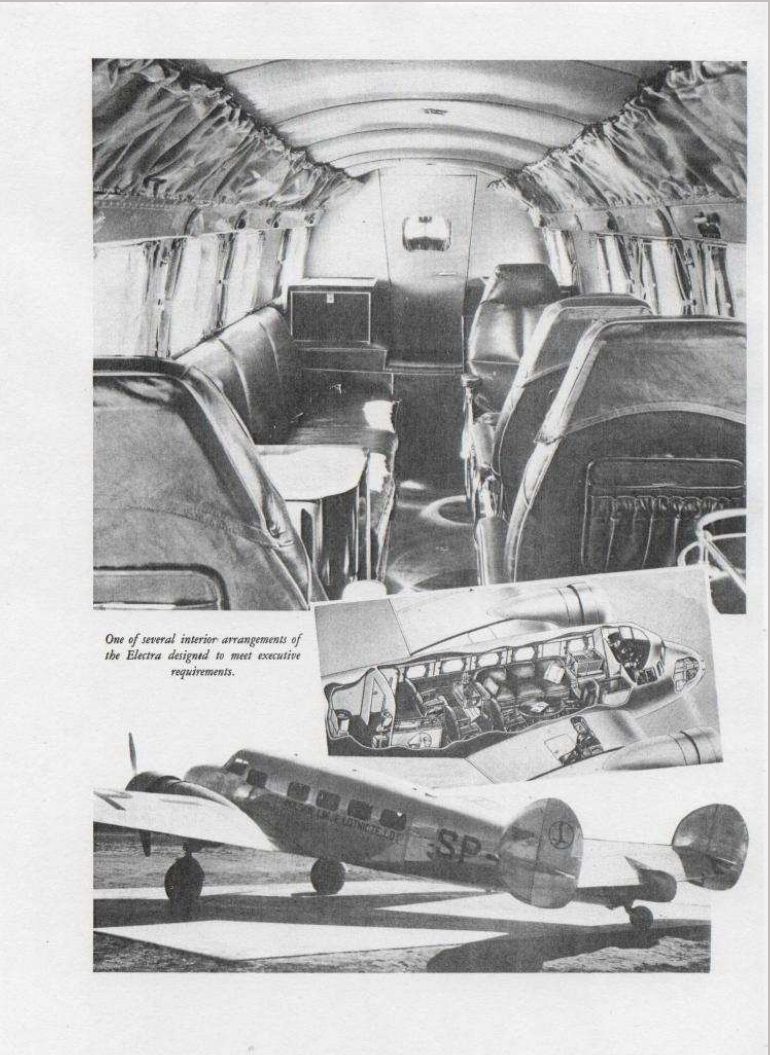

The Lockheed Model 10 was designed primarily by both Hall L. Hibbard and Lloyd Stearman, who was then serving as the president of Lockheed. In line with Lockheed’s convention for naming airplanes for celestial items, the name Electra was derived from a star located in the constellation of Taurus in the Pleiades star cluster. While the layout for a cabin to accommodate 10 passengers and two pilots was settled upon, the original design of the Electra was to feature a single vertical stabilizer on the tail. However, when a scale model was sent for wind tunnel testing at the University of Michigan, a young assistant aerodynamicist named Clarence “Kelly” Johnson made some recommendations to improve the Electra’s aerodynamic profile, including the removal of the single tail design for a twin tail configuration with two vertical stabilizers on the ends of the horizontal stabilizer. The change placed vertical fixed and control surfaces in the slipstream of each engine, improving controllability. A more surprising change Johnson suggested was to remove a wing-fuselage fillet, a common adaptation on many aircraft of the era, but found as unnecessary in his investigations. The changes were incorporated to the production aircraft, and when Johnson earned his master’s degree in aeronautical engineering, he would eventually join Lockheed and earn his place in aviation history.

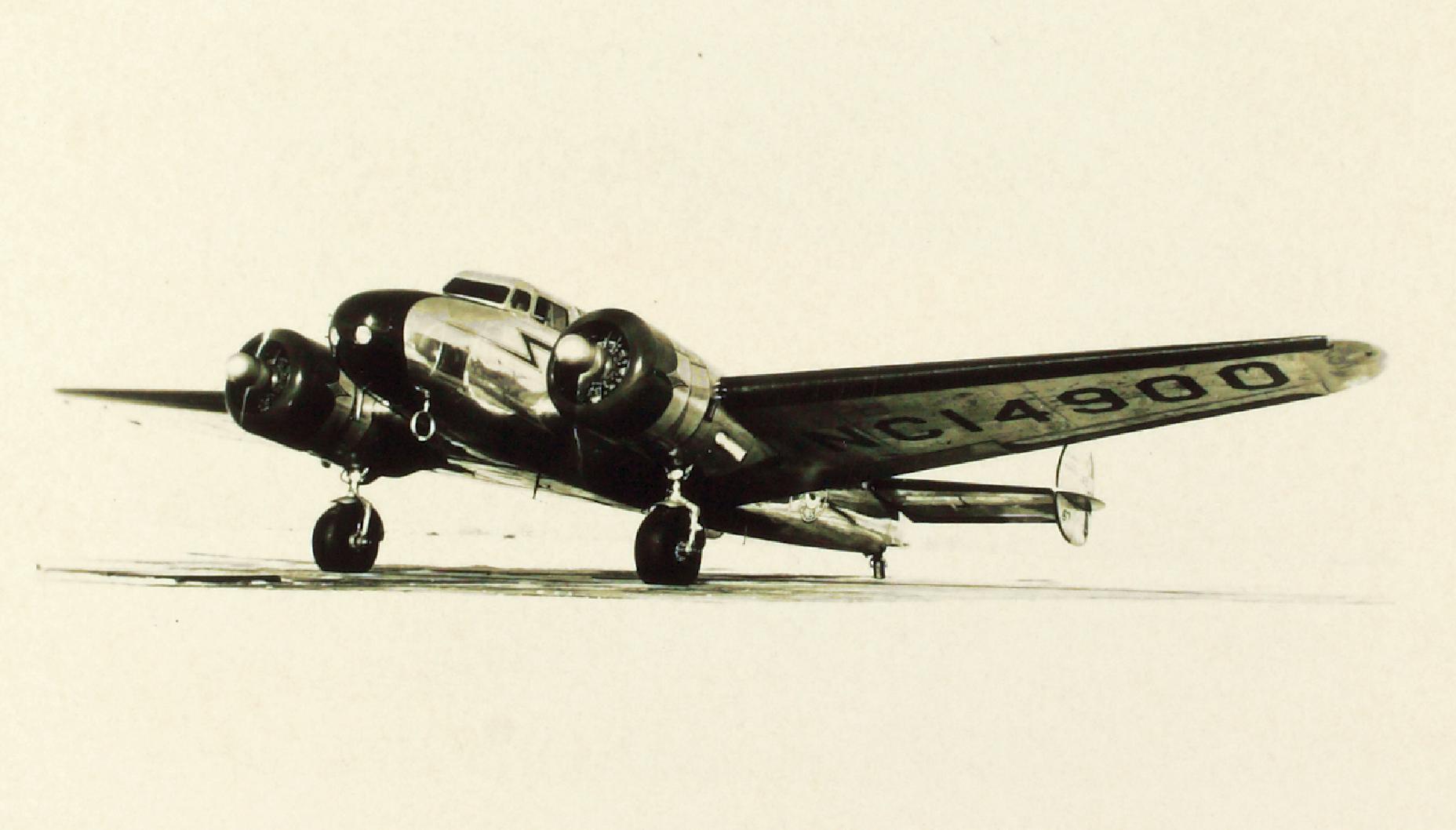

With the first prototype, c/n 1001, registration N233X, being constructed with the twin tail design suggested by Johnson, the Lockheed Model 10 Electra made its maiden flight on February 23, 1934, when Lockheed test pilot Marshall Headle took the aircraft to the skies above Burbank, California, making a short flight from the Lockheed factory airstrip to the adjacent Union Airport (present-day Hollywood-Burbank Airport).

Several distinguishing traits of the prototype from production model Electras were the forward-slanting windscreen and the wheel pants for the retractable landing gear legs. These features, though, were not adopted for production aircraft, with the wheel pants being considered unnecessary, saving little drag by enclosing the legs. The wheels were left exposed, and able to rotate, usually reducing damage to the airframe in the event of a gear-up landing. The forward-swept windscreen (similar to that seen on one of the Electra’s contemporaries, the Boeing Model 247) was intended to prevent instrument light reflection during night flights, but instead produced ground lighting reflections. By the fifth aircraft built, a rearward-slanting screen was used on all subsequent Electras.

Even before the Lockheed Model 10 Electra’s flight over Los Angeles, the design received interest from airlines across the United States. On of these was Northwest Airlines, which acquired the first prototype Electra, re-registered it as NC233Y, and flew it with the fleet number 60. Eventually, the aircraft went to Canada, receiving the civilian registration CF-BRG before being taken on strength with the Royal Canadian Air Force on August 2, 1940, as RCAF s/n 7652. It was destroyed by a fire on October 14, 1941, shortly after landing at RCAF Station Mountain View, Ontario.

Global Airline Buyers

Other American carriers included Braniff Airways, Continental Airlines, Delta Airlines, Eastern Airlines, and Pacific Alaska Airways among others. With the US government banning airlines from using single engine aircraft to carry passengers or even fly the mail at night in order to prioritize multi engine transports for passenger service, the Electra was perfectly used to fill the void that the single engine airliner such as the Northrop Alpha.

The Model 10 Electra received further interest from overseas customers as well, with Cuba’s Compañia Cubana de Aviación being the first Latin American operator of the type, followed by airlines in Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Panama, and Venezuela. In Europe, the Lockheed Model 10 Electra saw success with British Airways Ltd. (a separate entity from today’s British Airways), LOT Polish Airlines and with the then flag carrier of Romania, LARES (Liniile Aeriene Române Exploatate de Stat [Romanian Airlines Operated with the State]). The Electra was also used in Canada by Canadian Airways and Trans-Canada Air Lines and in Australia with Ansett Airways, MacRobertson Miller Airlines (MMA) and Qantas.

For both domestic and foreign operators, the Lockheed Model 10 Electra was easy to fly and maintain, robust, and provided economical service to fly into smaller airports that could not operate larger aircraft, and in rough climates from the Canadian North to the Amazon River and the Australian Outback, the aircraft could be adaptable to operate from remote unpaved airstrips.

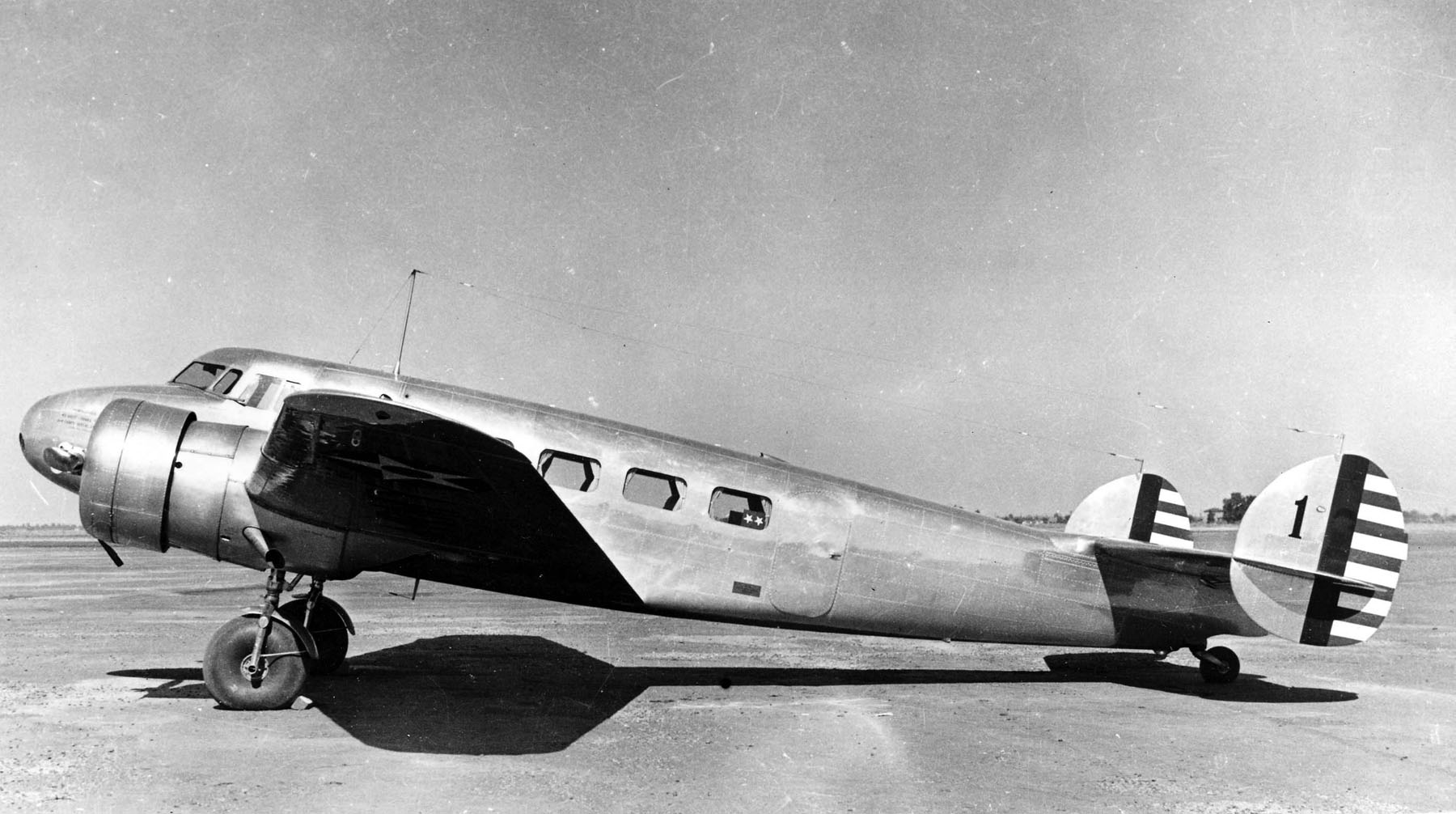

Military VIPs

The Lockheed Model 10 Electra also attracted attention from military branches around the world. In addition to its use as a VIP transport with the US Army Air Corps, Navy, and Coast Guard, Lockheed Model 10 Electras were used as military transports and liaison aircraft for high-ranking officers in the Argentine Air Force, Brazilian Air Force, the Royal Canadian Air Force, Honduran Air Force, Nicaragua Air Force, Royal Air Force and the Venezuelan Air Force, while a singular example (designated the KXL1) was built for the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service to be used for evaluation purposes. One example, Electra 10-A NC14946 “The Phantom of the Sky” was shipped to Spain aboard the armed merchantmen Mar Cantábrico during the Spanish Civil War was intended be received by the Spanish Republican Air Force but was instead captured by the Spanish Nationalists and used as a liaison aircraft not only for the duration of the civil war but well into the 1940s.

In all, between August 1934 and July 1941, the Lockheed Corporation built 149 Model 10 Electras for civilian and military use around the globe, with the variants distinguished primarily through the different types of American-built air-cooled radial engines used to power them. The most widely produced variant of the Model 10 Electra was the Model 10-A, of which 101 were built. These were powered by two Pratt & Whitney R-985 Wasp Junior nine-cylinder engines, with each engine producing 450 hp. Of these, five were produced for the US military, with the US Army Air Corps receiving three Y1C-36s (later C-36s/UC-36s). The US Navy received one that was designated as the XR2O-1 and used a transport for the Secretary of the Navy, while one example, the Y1C-37, was used as a personal transport for the Chief of the National Guard Bureau, and this aircraft went on to receive the designations C-37 and UC-37. During WWII, fifteen civilian 10-As were requestioned for use by the US Army Air Force and flown as utility transports under the designation C-36As/UC-36As for the rest of the were until they were sold as surplus back to the civilian market.

After the Model 10-A, Lockheed produced eighteen examples of the Model 10-B, which were powered by two Wright R-975 Whirlwind nine-cylinder engines, each producing 440 hp. One of these was built for the US Coast Guard as the XR3O-1 to serve as a transport for the Secretary of the Treasury, as the Coast Guard was managed by the Department of the Treasury from its inception in 1790 until 1967. Of the 18 Model 10-Bs built, seven were impressed into service with the USAAF during WWII and designated as C-36Cs/UC-36Cs.

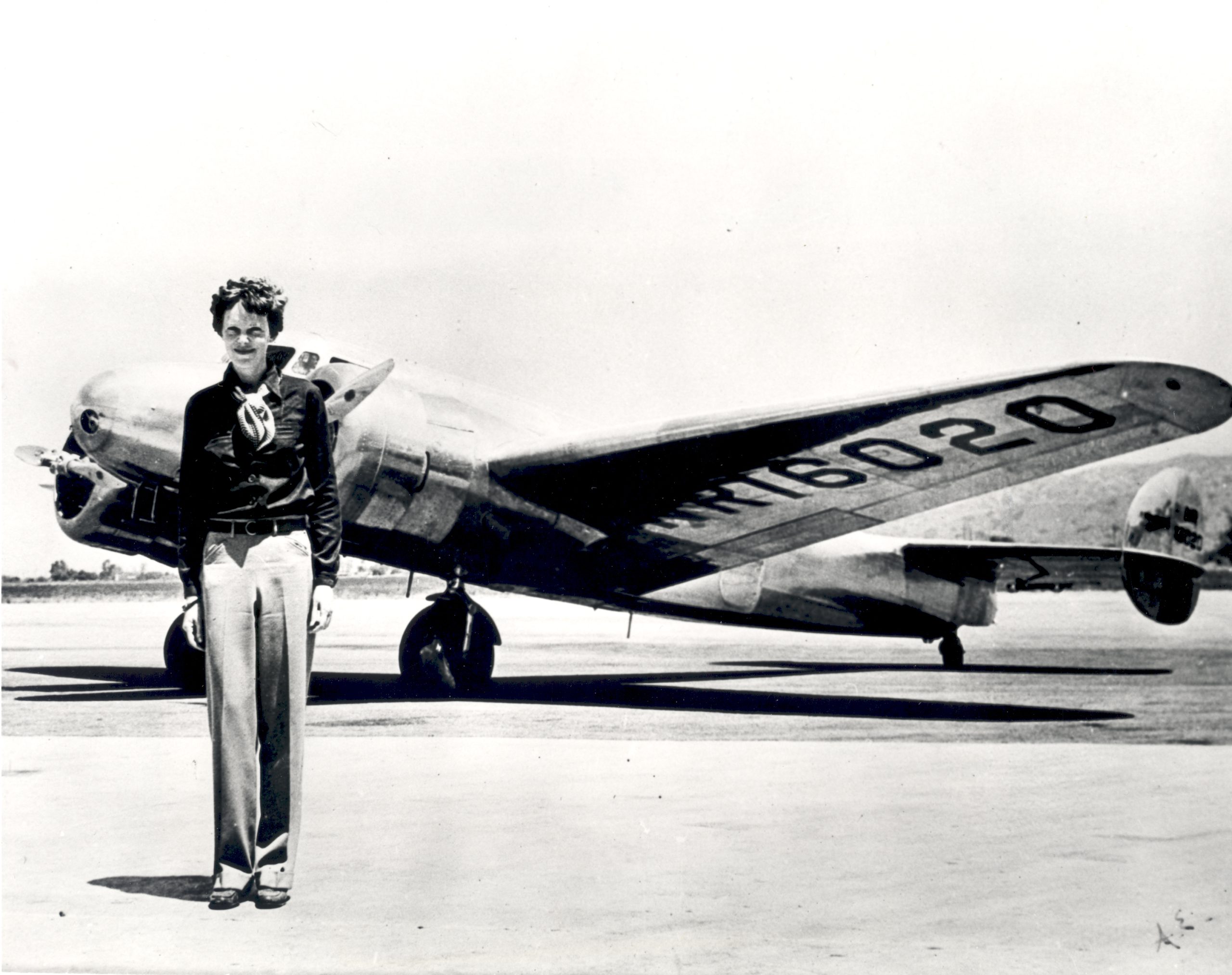

In order to fulfill an order for Pan American Airways, Lockheed built eight of the Lockheed 10-C model, which was powered by two 450 hp Pratt & Whitney R-1340 Wasp radial engines. With the planned 10-D military transport never leaving the drawing board, the next variant of the Model 10 Electra became the Model 10-E, which was also fitted with the R-1340 engine. Fifteen 10-Es were built, including perhaps the most famous example of the Model 10 Electra, c/n 1055, NR16020, the last aircraft flown by Amelia Earhart.

Having set numerous records flying Lockheed Vegas, Earhart was now determined to become not only the first woman to fly around the world but the first to fly around the world while tracing the Equator. Having become a guest lecturer at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, where she advised female students pursuing careers in aviation, the university established the Amelia Earhart Fund for Aeronautical Research, which raised funds for her to purchase a new Lockheed Electra, along with Earhart’s husband, the publisher George Palmer Putnam, who placed an order for a customized Electra in March 1936. At the Lockheed factory in Burbank, Electra 10-E c/n 1055 was modified with four auxiliary fuel tanks in the passenger cabin, the omission of passenger windows in the cabin, a navigator’s station aft of the cabin fuel tanks, a Sperry autopilot system and additional long-range radio and navigation equipment. By July 1936, the modified Electra was ready to begin flight testing, and Earhart mad her first flight in the aircraft on July 21, with Lockheed test pilot Elmer C. McLeod instructing her in flying the aircraft. Three days later, on Earhart’s 39th birthday, she accepted the aircraft, which she called her “flying laboratory”, which was registered as NR16020 (R – restricted for passengers). With no less than ten fuel tanks, Earhart’s Electra had a total fuel capacity of 1,151 gallons.

As Earhart made her final preparations through the remainder of 1936, she had NR16020 stored in a hangar owned by her technical adviser and Hollywood film pilot Paul Mantz at Union Air Terminal in Burbank. But in March 1937, she was ready to begin her flight, which would see her fly east-to-west. On March 17, 1937, Earhart took off from Oakland, California bound for Wheeler Army Airfield, Hawaii, along with Paul Mantz and navigators Harry Manning, a highly seasoned sea captain and radio operator for the US Merchant Marines and United States Lines, who was also a qualified pilot, and Fred Noonan, another maritime navigator who had also helped Pan American Airways establish air routes across the Pacific for its Clipper flying boats. Two years prior, in 1935, Earhart had flown solo from Wheeler Field to Oakland in a Lockheed Vega 5C (which you can read about HERE). They arrived at Wheeler Field on March 18, 15 hours, 47 minutes after departing Oakland. From there, Paul Mantz took the Electra on a test flight on March 19, landing at Luke Army Airfield on Ford Island, in the middle of Pearl Harbor (this airfield was later taken over by the US Navy as Naval Air Station Ford Island). But disaster struck on March 20, as Earhart, Manning, and Noonan began the takeoff roll to begin the next leg of their journey to tiny Howland Island, some 1,896 miles (3,052 kilometers to the southwest), Electra NR16020 ground looped at Luke Field, with the landing gear collapsing. After this accident, Earhart was forced to abandon her first attempt and shipped the damaged Electra back to the Lockheed factory at Burbank for repairs.

Two months later, on May 20, 1937, Amelia Earhart began her second attempt to fly around the world in the freshly repaired Lockheed Electra NR16020 with a flight from Oakland to Burbank, California. This time, she would be flying west-to-east, and with Fred Noonan being the only other crewmember on board. After spanning the southern United States with stops in Tucson, Arizona, New Orleans, Louisiana, Miami, Florida, and San Juan, Puerto Rico, Earhart and Noonan covered three-fourths of their route, crossing the Caribbean Sea, the south Atlantic Ocean, the Sahara Desert, the Arabian Sea, the Indian subcontinent, the Gulf of Thailand, the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia), the Timor Sea, and the Arafura Sea. By June 29, 1937, they had flown in from Darwin, Australia to Lae in what is now Papua New Guinea. After a four-day layover period in Lae, Earhart and Noonan set off on July 2, 1937, in Electra 10-E NR16020 for Kamakaiwi Field on the tiny speck of coral rock known as Howland Island, where they would refuel and rest before setting off for Hawaii, then onto the last leg of their flight, Oakland Airport, California.

However, as Earhart and Noonan get within radio range of the US Coast Guard cutter Itasca, it became evident that despite the fact that Earhart’s messages were clearly heard by the crew of the Itasca, and Earhart was able to receive and respond to communications from the Itasca, she was unable to get a radio-direction finder (RDF) bearing on the Itasca’s position to guide her and Noonan to Howland Island. Around 10am local time, the Itasca stopped receiving signals from the Electra, and despite the US Navy sending dozens of ships and airplanes to scour the Pacific for any sign of Amelia Earhart, Fred Noonan, and their Lockheed Electra, no such remains were uncovered. Noonan was declared dead in absentia on June 20, 1938, and Earhart on January 5, 1939.

Faster or Bigger Electras

Even as the Lockheed Model 10 Electra was at the height of its success, Lockheed used the Electra as the inspiration for subsequent twin-engine transports, from the Model 12 Electra Junior to the Model 14 Super Electra, which in turn lead to the Lockheed Model 18 Lodestar. These later models also lead to some of the most capable American patrol bombers of WWII, from the Lockheed Hudson, originally developed from the Model 14 for the British, to the PV-1 Ventura and the PV-2 Harpoon.

There was even a high-altitude variant of the Lockheed 10-E Electra with a pressurized cabin flown by the US Army Air Corps as the Lockheed XC-35, which led to the USAAC winning the 1937 Collier Trophy for the XC-35’s development, and in turn, the XC-35 would provide valuable lessons for the development of other aircraft with pressurized cabins, such as the Boeing 307 Stratoliner and the B-29 Superfortress.

Surviving Electras

Of the 149 Lockheed Model 10 Electras built, at least 12 are known to have survived to the present day, of which two are presently airworthy. The oldest among these is serial number 1011, which is preserved at the Pima Air and Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona. Originally delivered from the Lockheed factory to Northwest Airlines on December 21, 1934, as NC14620, fleet no. 64, the aircraft was later flown by Hanford Airlines (later Mid-Continent Airlines). From June 8, 1942, to March 21, 1944, the aircraft was flown by the US Army Air Force as a C-36A/UC-36A with the serial number 42-56638 before returning to civilian work. From 1953 to 1962, the aircraft was flown by the Honduran Air Force as FAH-104 before returning to the United States. At one point, the aircraft was part of an aircraft collection at Ontario, California known simply as The Air Museum (later becoming the Planes of Fame Air Museum) before ending up at the Pima Air and Space Museum, where it is displayed in its original Northwest Airlines scheme and is on long-term loan from the National Museum of the United States Air Force.

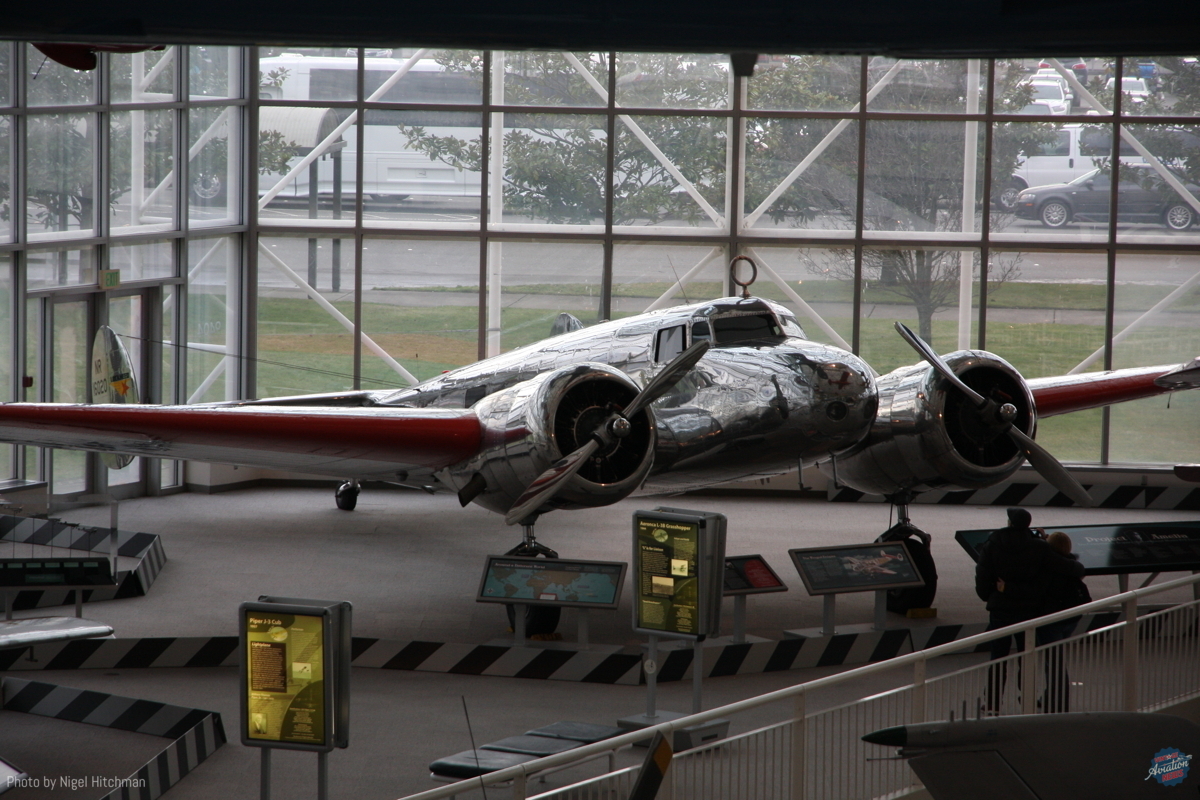

Next is serial number 1015, which is now part of the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington. Like previous example, s/n 1015 also built as a Model 10-A for Northwest Airlines, becoming NC14900, fleet no. 67. After being impressed into the US Army Air Force during WWII, it became C-36A/UC-36A s/n 42-57213. After serving in the USAAF, it was sold as surplus to the Brazilian Air Force, becoming s/n FAB 1002. It re-entered civilian life in Brazil, flying for the-then flag carrier Varig, which converted the aircraft to the standards of a 10-E with two Pratt & Whitney R-1340 engines as opposed to its original Pratt & Whitney R-985 Wasp Juniors.

After returning to the United States, the aircraft went through several owners before being used by pilot and aviation historian Linda Finch to retrace Amelia Earhart’s flight to commemorate both the 60th anniversary of Earhart’s last flight and the centenary of her birthday. She departed Oakland International Airport on March 17, 1997, and she arrived back at Oakland 73 days later on May 28. Though she did not land at Howland Island, she dropped three wreaths as she neared the end of her flight. In 2013, the Museum of Flight in Seattle secured enough donation funds to purchase the aircraft (which we at Vintage Aviation News covered HERE), and it was flown to the museum for one last flight before going on permanent display, still configured as Amelia Earhart’s Electra, NR16020.

Electra 10-A s/n 1026 was originally delivered to Braniff Airways from the Lockheed factory as NC14937 on June 10, 1935, before flying for Northeast Airlines, Capitol Air Service, and during its tenure with Provincetown-Boston Airlines, it was among the last Model 10 Electras to carry passengers in the US well into the 1970s with the registration N38BB. Later, the Electra was placed on static display at the Oakland Aviation Museum in Oakland, California before being moved into storage by a private owner. However, there is an effort underway to raise funds to purchase the aircraft for an airworthy restoration project (which we have also reported on HERE).

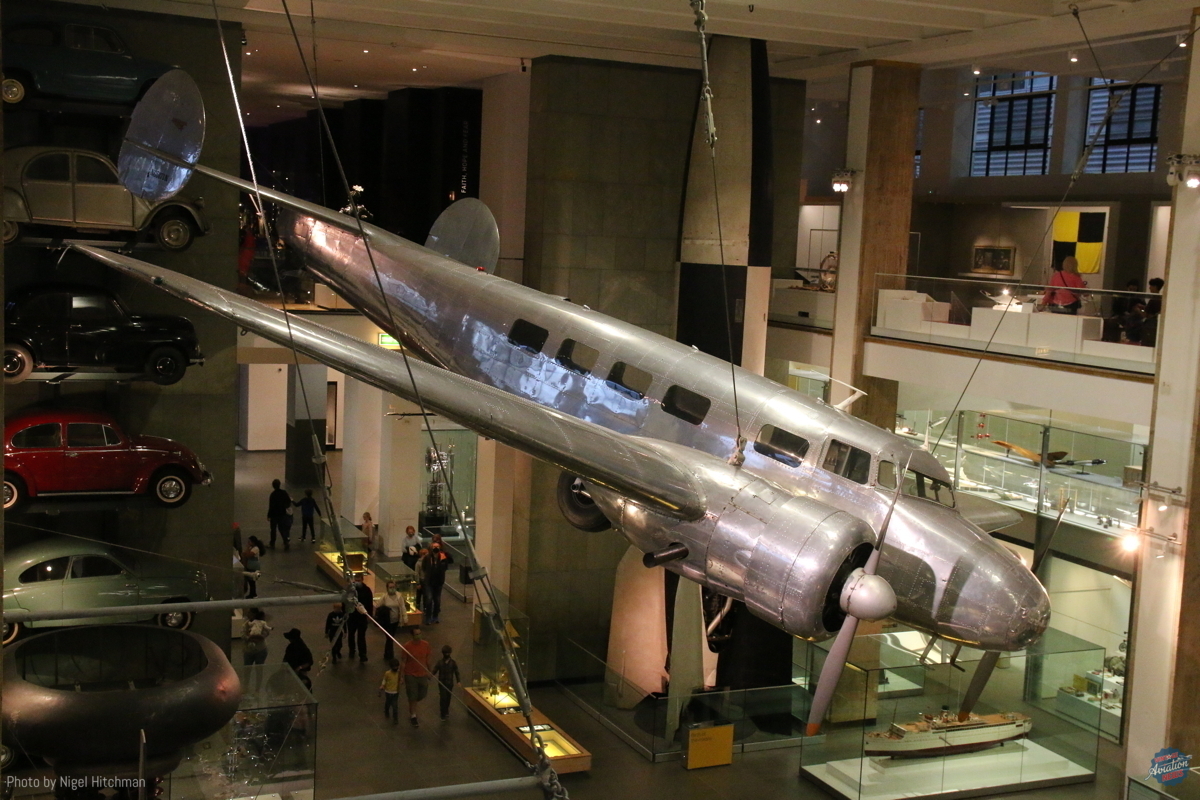

Electra 10-A c/n 1037 was originally delivered on September 24, 1935, to Eastern Airlines as NC14959 before flying for Boston-Maine Airways as NC243, then flew for Capitol Air Services as N5171N. After a brief period of display at the Wings and Wheels Museum in Orlando, Florida from 1979 to until the museum’s closure 1981, the aircraft was acquired from Wings and Wheels Museum owner and Korean War USAF fighter ace Dolph Overton in 1983 by the Science Museum of South Kensington, London. After determining that using a ferry permit to fly the aircraft would be cheaper and quicker than disassembling it for shipment. As such, the aircraft was given the UK registration code G-LIOA, and was flown across the North Atlantic via stops in Goose Bay, Labrador, Kangerlussuaq (Søndre Strømfjord), Greenland, Reykjaavik, Iceland, and Shannon, Ireland. Now, the aircraft is presently displayed at the Science Museum in South Kensington, suspended from the ceiling, after a number of years in store. (More on this aircraft HERE)

One surviving Electra that has been prominent as of late has been construction number 1042. Originally delivered to Pan American Aviation as NC14972, the aircraft also saw service in Mexico with Compañía Mexicana de Aviación and in Brazil with Panair do Brasil and Varig before returning to the United States to fly with Provincetown-Boston Airlines before being used a skydiving aircraft by the Zephyrhills Parachute Center in Florida. In 1979, the aircraft was acquired by the Wings and Wheels Museum of Orlando, Florida, but the aircraft was forced to be stored outside in the Florida humidity, and the museum itself closed in 1981, and auctioned off its collection of vintage airplanes and automobiles. Eventually, the old Electra was acquired on August 3, 1982, by flight instructor Grace McGuire, who re-registered it as NR1602D and named it ‘Muriel’ after Amelia Earhart’s sister Muriel Earhart Morrissey. McGuire had planned to recreate the 1937 flight, but due to health issues was forced to abandon her plan. However, the aircraft, which had been restored at Gillespie Field in El Cajon, California, was made available for the new Amelia Earhart Hangar Museum at Amelia Earhart Airport in Earhart’s birthplace of Atchison, Kansas.

The museum was officially opened to the public on April 14, 2023, and the Electra ‘Muriel’ is the centerpiece of the museum, which seeks to inspire children to pursue careers in aviation. (Read our reports on the aircraft and the museum HERE and HERE)

One of the last Electras built as a dedicated military transport, Model 10-A s/n 1052, can be found at the New England Air Museum (NEAM) in Windsor Locks, Connecticut. It was delivered to the United States Navy as XR2O-1 Bureau Number 0267 to serve as the transport for the Secretary of the Navy, based largely out of NAS Anacostia, Washington, D.C. After being declared surplus by the Navy, the aircraft went through several owners, from oil companies to airliners. By 1984, s/n 1052 was purchased by United Technologies to re-create the 1937 flight of Amelia Earhart in an aircraft that was only three serial numbers removed from Earhart and Noonan’s Electra. However, circumstances prevented this flight from occurring, so United Technologies donated the Electra to the New England Air Museum, who then restored it in the markings of a Northwest Airlines Lockheed Model 10 Electra. (More this aircraft from the NEAM HERE)

Among the scarce few airworthy Model 10 Electras is one based in Prague, Czech Republic. It is s/n 1091, registered as OK-CTB. Originally built at the Lockheed plant in Burbank, California, it was delivered to the Bata Shoe Company in Zlín, Czechoslovakia. Being one of the largest footwear companies in Central Europe, this Electra, registered as OK-CTB, was not only used to carry company executives on official business, but also flew around the world on a publicity tour. But with the Munich Conference of 1938 forcing Czechoslovakia to give up the Sudetenland region that neighbored Nazi Germany, it was evident that the Germans would not be satisfied with leaving the rest of Czechoslovakia alone, the Bata company sent their Lockheed Electra out of the country before Germany marched in. In March 1939, the aircraft was flown through Poland, Romania, Italy, and France before arriving in England, where the aircraft was disassembled and shipped across the Atlantic back to the United States in May 1939, where it then proceeded northwards to Canada, being added to the Royal Canadian Air Force on September 11, 1940, as RCAF 7656.

The Electra remained in service until May 2, 1946, when it was declared surplus. With the Soviet Union now fostering a devastated Czechoslovakia to become another buffer state for the USSR during the Cold War, Model 10-A 1091 remained in North America, going through a series of owners before being acquired by Czech tech billionaire Ivo Lukačovič, who had the aircraft restored in the United States back to its original pre-war Czechoslovakian markings and brought it back to join his collection of vintage aircraft at Točná Airport in in the village of Točná, near Prague. (Točná Airport has a website with further information on the aircraft HERE)

Two Lockheed Model 10 Electras can be found in museums in Canada. One is Electra 10-A s/n 1112, which was delivered from the Lockheed factory to Trans Canada Airlines (TCA) as CF-TCA on September 25, 1937, to October 23, 1939, when it became part of the Royal Canadian Air Force as RCAF 1526. On January 16, 1946, RCAF 1526 was stricken off charge from the RCAF and returned to being a civilian aircraft. The aircraft saw postwar airline service in the United States, flying for Wisconsin Central Airways as N79237 and later for Midway Airlines as N1285. In 1961, the aircraft was damaged during a belly landing at Willow Run Airport in Ypsilanti, Michigan. The owners wrote the aircraft off, and the airport planned to use the old plane or firefighting practice but was saved by mechanic Lee R. Koepke in 1962, who restored the aircraft to airworthiness with the registration number N79237.

Five years later, in 1967, he joined pilot Ann Pellegreno, copilot William Payne, and navigator Bill Polhemus in making the first re-creation of Amelia Earhart’s fateful 1937 flight using Electra 10-A N79237. After leaving Willow Run for Oakland, California on June 7, 1967, they set off on June 9 from Oakland on the round-the-world flight. Following the same flight path Earhart and Noonan took, they made a flyover of Howland Island on July 2, 1967, the 30th anniversary of the disappearance of Amelia Earhart, Fred Noonan, and their Lockheed Electra. On July 7, they successfully completed the round-the-world flight by landing at Oakland International Airport. Three days later, on July 10, they flew the aircraft back to Willow Run. One year later, in 1968, Air Canada (the successor to TCA) purchased the airplane, restored it to its original TCA markings, and donated it to the Canadian Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa, Canada, where it remains on display today.

The other Lockheed Model 10 Electra on display in Canada can be found at the Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada (RMWC) in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Built as Model 10-A s/n 1116, it was delivered to Trans Canada Airlines on October 13, 1937, and served with the registration CF-TCC. Later flown by the Canadian Department of Transport, the aircraft made its way back to the United States as N3749. While on vacation in Florida in 1984, an Air Canada employee who was aware of the aircraft’s history alerted the company to the aircraft’s status. Air Canada then purchased the aircraft, shipped it back to Canada, and had it restored by Air Canada employees. On March 18, 1986, the aircraft made its first post-restoration flight under its original Canadian registry and was flown the following year to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Trans Canada Airlines before being donated by Air Canada to the Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada in 2022. (More on the aircraft HERE)

At the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida, there is a civilian Lockheed 10 Electra painted as a Navy R2O-1. Originally built as Electra 10-A s/n 1130, the aircraft was flown by the Australian airline MacRobertson Miller Airlines (MMA) as VH-ABV with the name ‘Gascoyne’. Later re-registered as VH-MMD, it was returned to the United States in 1954 and operated for various owners before entering the NNAM’s collection in 1996, where it has since been repainted as a Lockheed R2O-1.

Down in New Zealand, Electra 10-A s/n 1138 is on display at the Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT) in Auckland, New Zealand. Originally flown as NC21735 by Standard Oil Co., the aircraft later flew for Interstate Aircraft Co. of Kansas City, Kansas until it was exported to New Zealand and flown by Trans-Island Airways (TIA) as ZK-BUT with the name Spirit of Tasman Bay. On February 18, 1959, the aircraft ground-looped at Christchurch Airport, and being considered uneconomical to return to service, was used for training airport first responders on emergency cabin rescue procedures by the Department of Civil Aviation. By 1966, the MOTAT was interested in acquiring ZK-BUT, along with the fuselage of Lockheed 10-A Electra s/n 1095, ZK-AFD, which flew for Union Airways with the name Kuaka (Māori for bar-tailed godwit). It was originally intended to have ZK-BUT serve as a source of spare parts to complete ZK-AFD, but when it was realized that Spirit of Tasman Bay was more complete than Kuala, it was decided to restore ZK-BUT in the markings of ZK-AFD, which is how the aircraft appears on display to this day in the MOTAT’s aircraft display hangar.

The other Model 10-A Electra currently flying today is s/n 1145, owned by Rob Mackley of Auckland, New Zealand, where it flies as ZK-AFD. This aircraft was originally sold by Lockheed on June 1, 1941, to LAN Chile (Línea Aérea Nacional de Chile (National Air Line of Chile)) under the registration codes CC226, CC-LGN-507, CC-CLG-0005, and CC-CLEA-231 before returning to the United States, even going as far north as Alaska before being exported to New Zealand. The aircraft flies with two schemes on it. The starboard side commemorates its service with LAN Chile, while the port side is painted in the colors of the aforementioned ZK-AFD Kuala, whose fuselage is in storage at the Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT). Once again, we at Vintage Aviation News have written an article about this Electra as well, which you can find HERE.

Meanwhile, the sole XC-35 that was ever built, US Army Air Corps/Force serial number 36-353, was donated to the Smithsonian Institution by the U.S. Air Force in 1948, and is kept in storage at the National Air and Space Museum’s Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility in Suitland, Maryland.

Today, 91 years after the first flight of the Lockheed Model 10 Electra, it remains an aircraft that evokes a time when aviation was still burgeoning out and shrinking time and space as we knew it then. While the aircraft made be most well-known for its association with the disappearance of Amelia Earhart, the Electra provided service around the world as a passenger and executive transport and paved the way for a long line of transport aircraft developed Lockheed Aircraft, which also adopt the Electra for its first turboprop airline, the L-188 Electra.

Today in Aviation History is a series highlighting the achievements, innovations, and milestones that have shaped the skies. All the previous anniversaries are available HERE

![Today in Aviation History: First Flight of the Lockheed Model 10 Electra 51 The Electra's Pratt & Whitney R-985s come to life. The aircraft is named Kuaka in tribute to an aircraft flown by Bill Mackley, owner Rob Mackley's father. [Photo by Ruth Christie]](https://vintageaviationnews.com/wp-content/uploads/ZK-AFD-20240131-Ardmore-Ruth-Christie-04-scaled.jpg)

![Today in Aviation History: First Flight of the Lockheed Model 10 Electra 52 Rob Mackley's Electra wears its original Linea Aerea Nacional de Chile markings on one side as seen in this photo taken at Ardmore Airport on December 6th, 2022. [Photo by Richard Currie]](https://vintageaviationnews.com/wp-content/uploads/ZK-AFD-20221206-Ardmore-Richard-Currie-02-scaled.jpg)

Electra also fly in Europe in Aeroput company in Yugoslavia. I think 6 planes fly for company.

Dear Nebojša, Indeed! For an aircraft produced in a relatively small numbers, the Lockheed 10 was widely used, from Canada to New Zealand, Britain to Yugoslavia. There is an excellent book on the Yugoslav Lockheed 10 story; ‘Yugoslav Electras – From Aeroput Airlines to RAF’. I have a copy and can highly recommend it: https://canfora.se/product/yugoslav-electras-from-aeroput-airlines-to-raf/

Your website’s numerous ads keep kicking me out of this comment section.

Were there production flaws in 1930’s aircraft that resulted in deviations fro projected flight paths, unbeknownst to the owner?

The short answer, Jeff, is ‘No’. Earhart’s aircraft was fitted with a bespoke navigation suite, and Noonan was using the best equipment available at the time. They had successfully managed to almost completely circumnavigate the globe, before missing a dot (island) in a vast ocean. A small error, an unknown change of winds would be all it took for that to happen.

Kudos, Adam! Your well-researched history of this Lockheed type was thoroughly enjoyed!