Story by Daniel Garas

Naval History and Heritage Command

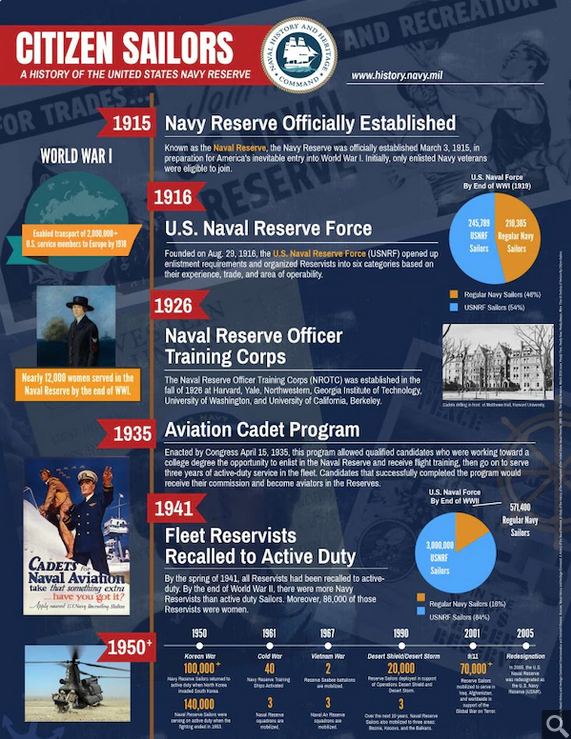

On the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, the destroyer USS Ward (DD 139) was conducting a patrol off the entrance to Pearl Harbor when at 3:57 a.m., she was informed of a periscope sighting by the coastal minesweeper USS Condor (AMC 14). The submarine was Japanese and Ward sprang into action as her No. 1 gun crew fired a shot that passed over the submarine’s conning tower. The crew of Ward’s No. 3 starboard side gun fired next and landed a direct hit that caused the submarine to heel over and sink.

The saga of Ward was unique in two ways. First, and most glaring, was that her fight with the Japanese happened several hours before the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor. The second was that the crew of the No. 3 gun on Ward was made up entirely of Navy Reservists. The fact that the crew was made up of Reservists would not be a surprise to anyone serving in the Navy at the time. At the outbreak of World War II, the U.S. Navy Reserve was ready to fight as they had begun mobilizing months prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

A Society of Citizen Warriors

America has been a society of citizen warriors since its inception. Volunteers have always been used to swell the ranks in time of crisis—from colonial militias, to the Reserves and National Guard of today. While the concept is often presented as a romantic embodiment of democratic ideals and citizenship, the real reasons for militias were often far more about economics—militias were cheap. Unfortunately, maintaining a large and well-trained Army is expensive. Navies cost even more. Prior to America’s entry into the conflicts of the late 19th and early 20th century, a standing Navy Reserve wasn’t deemed essential to the nation’s defense, or seen as fiscally responsible.

It wasn’t until May 17, 1888, that the first naval militia was established by Massachusetts. Manpower was provided by the state, while subsidies, equipment, and obsolete ships for training were provided by the federal government. Even then, state naval militias had limitations. Enlistment standards were lax; rules and agreements to mobilize were unclear, and unit capabilities were limited by equipment.

Furthermore, the men attracted to state naval militias didn’t fit the fleet’s notion of ideal recruits. Officers in militias were also elected by the men in their unit, which caused issues of legitimacy and respect for the regular fleet. Perhaps the biggest factor that drove the need for a federal naval reserve was the U.S. Navy’s transition from iron to steel ships in the late 1880s. Steel warships outfitted with new technology like internal-combustion engines, electricity, and radio, required a force of skilled tradesmen to operate them.

“Over There”

When World War I began, some saw America’s entry into the conflict as only a matter of time. To prepare, a federal naval reserve was officially established on March 3, 1915. Initially only enlisted Navy veterans were eligible to join, but with growing manpower issues and the threat of war looming, there was an obvious need for restructuring. Founded on Aug. 29, 1916, the U.S. Naval Reserve Force (USNRF) opened up enlistment requirements and organized Reservist into six classes based on experience, trade, and area of operability.

Mobilized USNRF Sailors bolstered the size of the fleet. Flush with manpower, the U.S. Navy, with considerable help from Great Britain, France, and Italy, was able to put over 2 million men on the continent of Europe in a year, with minuscule losses—a logistical triumph that is still impressive to this day. At the time, there was nothing on paper that made mention of prohibiting women from joining, and many took advantage of the opportunity. Suddenly, women who could quickly transcribe intelligence documents, found themselves just as essential as men manning a gun on a warship. By the war’s end, 11,275 women served honorably in the Naval Reserve in a variety of roles, including translators, draftsmen, fingerprint experts, camouflage designers, and recruiting agents. By the end of World War I, more than half of naval personnel were Reservists. Figures show that by Jan. 1, 1919, there were 245,789 personnel serving in the USNRF, out of a total naval force of 456,154.

The groundwork for the Modern Reserves

Despite its outstanding success, after World War I, the Navy went through a major drawdown. Economic realities and an American policy of isolationism would drastically reduce funding. Exacerbated by the Great Depression, the USNRF was forced to cut even more funds and prioritize its capabilities.

In an effort to do this, the Navy recognized the USNRF and made provisions to lay out the foundation for the modern Reserves. In 1925, the Naval Reserve Force was reorganized into the U.S. Naval Reserve and was made up of three classes: Fleet Naval Reserve, Merchant Marine Reserve, and the Volunteer Reserve.

Naval armories were constructed across the United States for Reservists to perform drills at, and policies, regulations, and efforts to recruit, train and retain them were developed.

Also around this time, during the fall of 1926, the Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps (NROTC) was established at six universities: Harvard, Yale, Northwestern University, Georgia Institute of Technology, the University of Washington, and the University of California Berkeley. The program eventually spread to schools around the country.

In return for several years of service to “Uncle Sam,” qualified candidates earned advanced training, received generous pay, and had a unique opportunity to serve in an exciting field of naval warfare. In return, the Navy would get access to a large, qualified pool of candidates for their officer corps. The pool of well-educated and trained officers, provided by the Reserves, proved instrumental in World War II. One other important areas of growth during the interwar period was naval aviation. Forward-thinking minds saw the need for more aviators, and the Naval Academy could not keep pace with providing newly commissioned officers for an expanding Fleet that now included an air arm.

To meet the demand, programs like the Aviation Cadet Program were enacted by Congress in April 1935. The program allowed qualified candidates—who had, or were working towards a college degree—the opportunity to enlist in the U.S. Naval Reserve, receive flight training, and go on to serve three years of active duty in the Fleet. The program successfully produced a large number of pilots in short order, for a relatively low cost. Applicants who successfully completed the program would receive their commission and become naval aviators in the Reserves. Those who did not simply went on to fulfill their regular enlistment contracts.

By the beginning of 1941, war with Japan seemed imminent, and by Spring all Fleet Reservists had been recalled to active duty. When USS Ward saw action on Dec. 7, the Reserves were already ready to fight. Throughout World War II, there were actually more Navy Reservists than active duty Sailors serving in the U.S. Navy. Records show that by the time the war finished, over three million Naval Reserve Sailors were serving on active duty, comprising 84 percent of the Navy. Among them were 86,000 women.

New Challenges in a New Era

After witnessing the success of the Navy Reserve in World War II, and with an understanding of the growing threat from the Soviet Union, the Navy vigorously sought to retain trained and qualified Reservists. By 1948, over one million Sailors were enrolled in the Reserves. To support the influx of Reserve personnel, the Navy constructed 300 modern Naval Reserve Training Centers. In the decades since the end of World War II, Reservists have continued to play an important role in augmenting active duty whenever called upon:

At the outbreak of the Korean War on June 26, 1950, over 100,000 Navy Reserve Sailors returned to active duty for service in the Fleet. At the end of fighting in 1953, there were 140,000 Reservists serving on active duty.

Throughout the various flashpoints of the Cold War, the Navy Reserve maintained its readiness and supported the Fleet when necessary. Forty training ships and three Naval Reserve squadrons were activated in response to the Berlin Crisis of 1961. In Vietnam, two Reserve Seabee battalions and three Reserve squadrons were mobilized.

In 1990, the invasion of Kuwait resulted in the mobilization of 20,000 Reservists. Reservists contributed in Bosnia, Kosovo, and the Balkans.

More than 70,000 Reservists have mobilized to serve in support of the Global War on Terror, and in 2005 the U.S. Naval Reserve was re-designated as the U.S. Navy Reserve (USNR).

Over the years, the USNR has undergone so many changes, both in title and organization. As old challenges are met, new ones arise, and one thing remains: the devotion, ingenuity and flexibility Reservists bring to the fight dramatically increase the effectiveness of our Navy.

Ready then. Ready now. Ready always.