Warbirds News, while often focused on the current state of vintage military aircraft, is also keen to share stories concerning the people involved with those aircraft whether in the present, or the past. We have here a terrific article written by Brendan McNally about a documentary film currently in production concerning a specific WWII bomber crew: Crew 713, the men who flew the B-24 Liberator known as Irishman’s Shanty.

Here is a look inside the WWII documentary film, CREW 713.

By Brendan McNally

Like a lot of kids who came of age in the decades following World War II, Alejandro “Alex” Mena grew up in that war’s shadow. Even through it had happened twenty years before he’d been born, reminders of it were everywhere, in books, magazines, movies and TV shows. When it came to interest in the war, kids of Alex’s generation tended to fall into two categories: those who couldn’t stand the subject and those who couldn’t get enough of it. Alex Mena fell firmly into the latter category.

Alex knew his dad, Nemesio Mena, had served in the war. But he never knew what he did. One day at a family get together, one of his cousins came up to him and exclaimed, ‘I didn’t know you’re Dad flew a B-17, that’s cool’. Alex didn’t either. He rushed to his Dad and said so, but his father quickly set him straight. ‘Heck no! I didn’t fly a B-17, I flew a LIBERATOR, the B-24’ Mena chuckles, remembering the encounter. His father’s obvious pride in his bomber showed through, even though he had probably last flown on a B-24 at least 30 years earlier. He learned that his father had been a radioman aboard a B-24 Liberator named The Irishman’s Shanty and that they had flown some very hairy missions over France and Germany during the summer of 1944. It wasn’t until much later that Alex would learn that they had been the first crew in their unit, the 492nd Bombardment Group, to complete a thirty mission combat tour. Unlike a lot of guys who’d been in combat, Nemesio Mena had never had much problem talking about what he’d been through. But then, he was career military and had also flown in Korea and Vietnam. “In each of those wars, he’d gone into harm’s way and the guys he was around were the same way. They tend to embrace it and so they’ll talk about it,” explains Alex.

Alex heard his father’s stories and he read the histories of the battles and went to the airshows. He grew older, but never lost his admiration for his father and his father’s generation.

After finishing school, Alex moved to Dallas, went to college at UT-Arlington and started working in the film industry. Working on everything from commercials, feature films and TV series, he was doing jobs as varied as grip/electric, script supervisor, art department, boom operator to assistant director. He started thinking he’d like to do his own films, but even though he had toyed with the idea of doing a documentary about his Dad’s WWII bomber experiences, he really wanted to shoot a Western for his first project. He knew full well that any documentary project was going to take years out of his life, and he didn’t feel he was in the right place professionally and personally to tackle such a large and ambitious project.

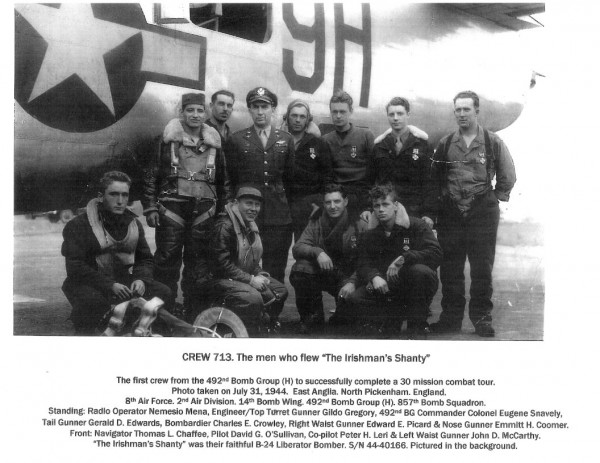

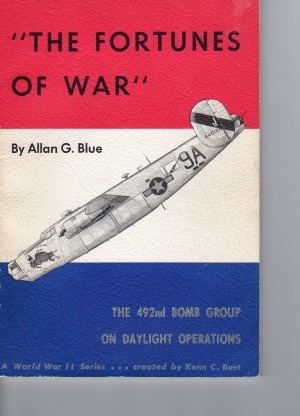

It was during a visit with his parents in El Paso that Alex Mena finally figured out he was destined to make a documentary about his Dad’s bomber crew. “I went to visit my folks in the Summer of 2007. I noticed that my dad had gotten a lot frailer and was not as healthy as he used to be,” recalls Alex, “while I was on this visit, I read several unit histories that my father owned about his old bomb group. Allan Blue’s “Fortunes of War” and Russell Ives’ “89 Days”. It was an epiphany, a light came on, and it was like, ‘I gotta do this!’ That’s when he decided to produce a documentary film about his father’s B-24 Liberator bomber crew. His parents had a crew photo in their den and Mena asked his father to identify the men. He promptly named the men and their crew position on the bomber. Mena marveled at his father’s recall, they had last flown together as a crew 63 years earlier. He realized he was witnessing the Band of Brothers syndrome. These men had bonded and formed an allegiance that only men who have fought in combat can experience. He would use this information to track down the other men from his father’s bomber crew.

He went back to Dallas and started putting together a plan. But before he could get the project going, his father died later that same year. For a while, Alex was devastated, but he decided not to give up. For the next two years Alex searched for other members of the crew to interview, but it turned out they were all dead as well. But sad as that was, he was also finding out their paths had not grown cold, for they had left behind much he could use and their story could still be told.

Alex remembers one conversation this way: “This one lady, her name is Virginia Picard, she was a widow of one of the waist gunners, and I found his name via an internet search. So I called this number and said, ‘I’m looking for Mr. Edward Picard,’ and she said ‘I’m sorry, he passed away.’ So I said, ‘Did he serve in the 8th Air Force?’ and she said ‘Yes.’ And I said, ‘Did he fly on a B-24 bomber?’ She said ‘Yes,’ and I said, ‘Was the name of the airplane called ‘The Irishman’s Shanty?’ and she said ‘Yesssss, who is this?’ A weird sort of elation came over me, I knew I had hit paydirt. so I introduced myself and told her what I was trying to put together. She was very happy to learn I was producing a film about the crew.”

Mrs. Picard shared Alex’s desire that their loved ones’ stories be told. As Mena located the other families of his father’s crew, he discovered that they also felt the same way and began sharing with Alex things from that period that their fathers and husbands had left behind. “Photos, letters, journals, military records” recalls Alex. “The daughter of the navigator sent me navigation charts that he used, not copies but the original navigation charts, including the one for June 6, 1944, D-Day! And I’m holding it in my hands! Holy Cow! To connect with the men and history in such a personal way was very moving.”

The widow of Charles Crowley, the bombardier, sent Alex approximately one hundred and fifty letters from 1943 to 1945 which Crowley had sent to her and his family. Crowley also kept a mission war diary and Alex’s dad kept a journal. Reading them, Alex could see how, with voice actors to read them aloud, they would make his film come alive.

Alex’s search went deeper. He got in touch with author Russell Ives and it turned out he’d conducted interviews with Barney Edwards, his dad’s old tail gunner from the crew. “He’d send Barney a list of questions and a blank cassette tape and over the next couple weeks, he’d dictate the answers by talking directly into the tape recorder. Ives sent the tapes to Alex. Alex originally planned to use the tapes the same way he would use the diaries; as source material, transcribed and then read out by actors. But when he heard Barney Edwards’ voice, it had an immediacy and connection that no actor could ever communicate. Alex realized he was finding gold.

Alex soon was in contact with two brothers who run the 492nd Bomb Group website. This site, (www.492ndbombgroup.com ) is maintained & operated by two sons of a 492nd veteran. “David and Paul Arnett have built not just one of the best military websites ever, they’ve built one of the best websites PERIOD” says Mena. Through them, he was soon in contact with the bomb group association and learned they were planning a reunion in July of 2008. Alex went to work and secured a film crew to travel with him to Minneapolis to interview these men. “Since all of the men who flew in my Dad’s crew were dead, I needed more voices-more source material for the film.” He found them in the veterans who were willing to tell him stories from those terrible months at North Pickenham. “We secured 8 precious interviews in those 3 days”. Those interviews would form the basis for the storyline of the film. Three more 492nd BG veterans would be interviewed in the next couple of years.

“As I started doing research about the crews and the bomb group, it’s like peeling an onion. Bits and pieces of new information start coming to you and fitting together and you realize ‘Holy Toledo, there’s a bigger story here!” Alex Mena was only beginning to learn that the 492nd Bomb Group had a unique, tragic, and almost entirely forgotten place in the annals of American military history.

In the late spring of 1944, when the 492nd Bomb Group’s four squadrons, (the 856th, 857th, 858th and 859th), flew to England, the air war over Hitler’s Fortress Europe seemed, for all intents and purposes, already won. The Luftwaffe might still have the planes, but their veteran fighter pilots were mostly all dead by then, replaced by green kids, who generally lasted only a few missions before being shot down. The Luftwaffe also didn’t have the fuel to keep them flying long enough to achieve any real proficiency. The American and British air forces had, on the other hand, learned and achieved much in the previous two years of bloody aerial combat. They’d learned about strategic bombing and how critical it was to have fighter escorts to protect the bombers. No matter how many machine guns a bomber had bristling from its fuselage, it was never enough to save them when the fighters swarmed on them. The only way to do that was to have plenty of Mustangs, Thunderbolts, Lightnings and Spitfires, to keep them away.

The key was coordinating coverage by the escort fighters. “The bombers would leave early and the fighters would take off hours later and meet them at certain agreed-upon coordinates,” says Alex. “If the fighters didn’t show up when they were supposed to, and the Luftwaffe were lurking, they’d take advantage of the situation.”

And that was what happened to the 492nd. They went into action on May 11, thirty bombers attacking the Auxerre marshalling yards near Switzerland. All aircraft returned to base, though two crash-landed due to fuel starvation. The next day they went up again, this time thirty-two aircraft against a target in central Germany. All returned safely. Two days later another mission, all aircraft returned home, though one crewman was killed by flak.

After that they had five days off. On May 19th, they went back into action, twenty six planes sent against a target in Brunswick, Germany. Eight bombers were lost. For the next nine days they flew five more missions during which time only one aircraft was lost. Then on the 29th of May, they attacked the refineries at Politz in Northern Germany and three aircraft were shot down, the O’Sullivan crew # 713 almost became the fourth casualty that day. Their plane was heavily damaged, with two engines on fire, a huge ragged hole in the side of the plane and a massive 10 man life raft hanging off the right rear stabilizer. With all of this, the crew somehow managed to keep the aircraft afloat and she limped back to North Pickenham. Pilot David G. O’Sullivan received the Distinguished Flying Cross for saving his crew and his aircraft that day.

For the next month, the 492nd flew missions in support of the Allied invasion of Europe, during which time their losses were minimal. One bomber collided with another on June 4. Another was shot down on June 15 and two more three days after that.

Two days and three missions later, they went after the refineries at Politz again. Thirty-five aircraft were sent, fourteen were lost. “On any given day, one of the squadrons had the day off,” explains Alex. “Three squadrons of twelve planes were sent out. The 856th sent out twelve planes and only one came back. Eleven planes were lost. Luckily, they didn’t lose all the men because some planes diverted safely to Sweden.” The day’s losses were staggering: 14 aircraft lost. 76 airmen killed in action. 22 prisoners of war and 41 internees. It was a grim day for the 492nd BG.

What happened was the American bombers were supposed to be protected by two successive groups of escort fighters. “At their briefing, the bomber crews were told, ‘From this point here, this fighter group will escort you. From this point, this group will,’” says Alex. “And at certain key moment in their mission, their fighter escorts failed to show up when they were supposed to show up. And in those five to ten minutes, the Luftwaffe took advantage of the situation. They got beat that way on three very costly missions.”

For the rest of June and into early July, the 492nd went back to flying relative milk runs; the group flew eleven missions with only one loss. The 12th mission on July 6th was against the shipyards at Kiel. Two aircraft were lost. Then on July 7th, they attacked Bernburg and twelve aircraft were lost. Crew 713 narrowly avoided disaster on this mission, missing a head on collision with another bomber. Their wing man was not so fortunate. The two planes collided and 20 airmen were killed in an instant. It was a sobering experience for the men aboard ‘The Shanty’ who witnessed the collision first hand. After that, the group flew 20 more missions in July (including the July 31st raid on Ludwigshafen which was Crew 713’s 30th and final mission) and early August with relatively low losses of 8 aircraft, but the damage had been done. By early August, the 8th Air Force had seen enough. Their losses were too great. An order was issued disbanding the 492nd. It was the first and only time in World War II that an American heavy bombardment combat unit was disbanded. In the 89 days that they were operational, the 492nd had flown sixty seven missions and dropped 3,643 tons of bombs. Their losses had been staggering. Of the seventy crews and B-24 bombers that had departed Alamogordo, New Mexico for England at the end of March, 1944, only 15 original crews remained. The bomb group had lost a staggering 55 aircraft, 234 airmen had been killed in action, and another 260 men were either prisoners of war or interned in Sweden and Switzerland. It was the highest losses of any single American combat unit during World War II.

But it didn’t end there. The 492nd would go on to suffer being wiped out twice. The first time had been at the hands of the German Luftwaffe, the second time was by the generals of the 8th Air Force. Rather than admit to such staggering losses, they resorted to a sleight-of-hand to make the losses go away. The 492nd BG unit designation was handed over to a secret OSS unit, the 801st, known as “The Carpetbaggers” who needed a cover for their clandestine activities against the Nazis. The new 492nd performed night drops of agents, releases of propaganda leaflets and other top secret activities. For reasons of national security, their existence remained secret for years after the war and as a result, the tragic and heroic record of the original 492nd remained secret as well. Now, nearly seventy years later, they have yet to receive any commendation or official recognition for their service or their sacrifice. Alex Mena hopes to change that.

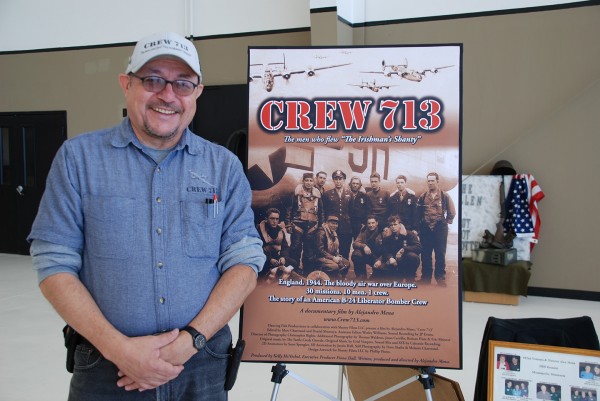

Six years in preparation, crew 713, Alex’s documentary film about the crew of The Irishman’s Shanty and the short and bloody history of the 492nd bombardment Group is getting closer to completion. But time is running out and there are still interviews to be conducted, animation storyboards to be built and music and editing to be completed. It is vitally important that the heroic contribution of these men not be forgotten a second time. Personal and corporate contributions are needed to get this film finished, so that future generations will remember the contributions of these brave men. To contribute to the film’s production fund, go to their website www.crew713.com and click on the Honor a Veteran by donating key on the home page.

Crew 713 has generated a lot of enthusiasm and support among many organizations including the Commemorative Air Force B29/B24 Squadron in Addison, TX. They have generously offered the use of their B-24A Liberator bomber, “Diamond Lil” for promotional and filming purposes. In addition the film has garnered support from the Frontiers of Flight Museum, The Cavanaugh Flight Museum, The Collings Foundation (Mena’s film crew flew and shot footage with their B-24, Witchcraft in 2010), the Memorial Trust of the Second Air Division USAAF-Norfolk, England and others. “We are really proud of the groups and organizations which have stepped up to support this project. I also have two amazing producers, Fiona Hall and Kelly McNichol, who have helped tremendously and kept this project moving forward. I am confident we will finish this film and make a lasting contribution to the memory of the men who flew in the 492nd Bomb Group. I’m sure my Dad would approve.”

The film is a labor of love for Alex Mena, and Warbirds News hopes that some of our readers may be able to help get the film completed, whether through their knowledge of events, or with additional funding. It is an important story, which simply must be told.

Richard Mallory Allnutt's aviation passion ignited at the 1974 Farnborough Airshow. Raised in 1970s Britain, he was immersed in WWII aviation lore. Moving to Washington DC, he frequented the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum, meeting aviation legends.

After grad school, Richard worked for Lockheed-Martin but stayed devoted to aviation, volunteering at museums and honing his photography skills. In 2013, he became the founding editor of Warbirds News, now Vintage Aviation News. With around 800 articles written, he focuses on supporting grassroots aviation groups.

Richard values the connections made in the aviation community and is proud to help grow Vintage Aviation News.

awsome story!

John Daniel McCarthy -first row on end at right. Would like to hear from any one about him or any of the crew. I was an AMM2/C US Navy WW2 and came from New Jersey same as “Jackie” McCarthy

John Mccarthy was my uncle. I met him once when I was a kid. He came to my house to see his sister (My Mother). He lived in NJ until the day he passed away. He had some problems and passed away in his early forties. My Father thought the world of him as my Mother did. Until reading this I had no idea what he accomplished.

Sincerely,

Bob Melick