Sea Hornet Resurrection

by Richard Mallory Allnutt

Pioneer Aero in Auckland, New Zealand recently announced that they have acquired the substantial remains of de Havilland Sea Hornet F.20 TT193, and will be restoring this unique ‘survivor’ to flying condition. They will be working with Aerowood, a company already hard at work building wings for deHavilland Mosquito FB.VI PZ474 currently coming together at AvSpecs Ltd. These two New Zealand-based companies have rebuilt all but one of the Mosquitos currently flying or under restoration to fly, in close collaboration with Glyn Powell, who developed the fuselage moulds. These skills will prove essential to restoring the Sea Hornet.

The de Havilland Hornet series of fighter and reconnaissance aircraft derived directly from the earlier Mosquito, using similar moulded plywood construction techniques, although it was a wholly new design. de Havilland started work on the DH.103 Hornet in November 1942, seeing the need for a long-range escort to cover the vast open spaces in the Pacific Theatre of Operations during WWII. While the war ended before its development was complete, the Hornet did reach front line service in the post-war RAF. The advent of the Jet Age, however, quickly saw the Hornet relegated to ancillary roles on the outer edges of Britain’s fading empire in the Far East. The type did see combat in the Malaya Emergency during the 1950s however, and excelled in the ground attack role. Its agility, ordinance load and especially its lengthy target loiter time proved highly useful.

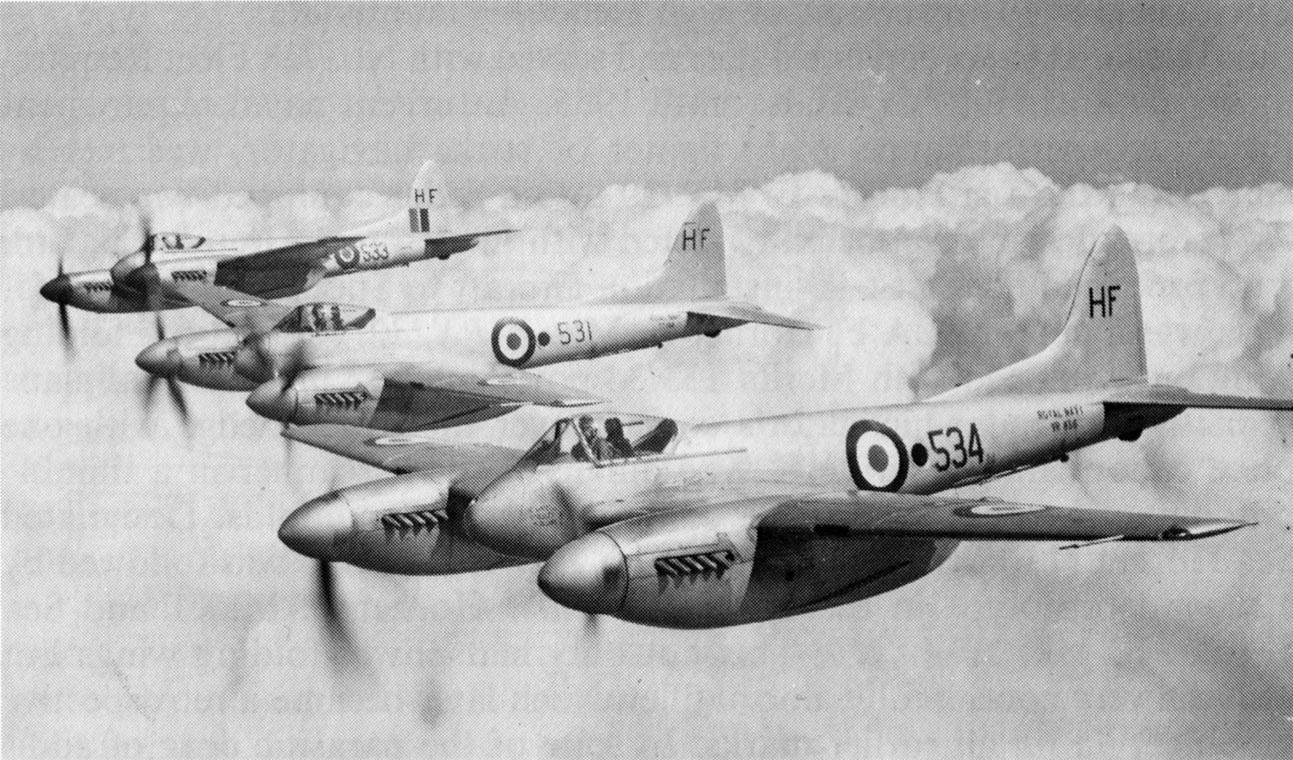

The Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm had its own variants, known as Sea Hornets. They had folding outer wings for service on carriers, along with a number of other naval modifications, such as slotted flaps for better low-speed flight characteristics while landing. Sea Hornet F.20s also had a pair of dedicated fuselage camera ports. The type was beloved by pilots for its speed and handling. In fact, the legendary British test pilot, Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown said of the type later in his life…

“Circumstances had conspired against the Sea Hornet in obtaining the recognition that it justly deserved as a truly outstanding warplane…in my book the Sea Hornet ranks second to none for harmony of control, performance characteristics and, perhaps most important, in inspiring confidence in its pilot. For sheer exhilarating flying enjoyment, no aircraft has ever made a deeper impression on me than did this outstanding filly from the de Havilland stable.”

However, the Hornet did have an Achilles Heal. The glue which deHavilland used to bond its plywood skins proved susceptible to breaking down in the high heat and humidity of the tropics. The resulting delamination problems, coupled with termite issues, caused the early retirement of the RAF’s fleet in the Far East. The last operational sortie by an RAF Hornet took place on May 21st, 1955, and the remaining airframes in the Far East were broken up on site.

While the Sea Hornet was an amazingly capable aircraft, it was unsuitable for operations from the smaller, Light Fleet Carriers which predominated in the post-war Royal Navy. Thus the type did not enjoy much service at sea, with only 801 Squadron flying the F.20 in front line service. The type did operate from a few naval land bases, including Hal Far on Malta, but the Royal Navy withdrew most of its remaining Sea Hornets to storage yards in Scotland by the early 1950s. Long-term outdoor storage of wooden aircraft in such a climate is never a practical solution, and the Sea Hornets didn’t last long. Most of these examples were in scrap yards by 1957.

Of the 209 Hornets and 178 Sea Hornets which deHavilland produced, neither the RAF, nor the Royal Navy thought to preserve one. The last known, substantially complete airframe, Sea Hornet NF.21 VW949, lingered on at Goodwood into the late 1960s, but even that ended up on the scrap heap in 1968.

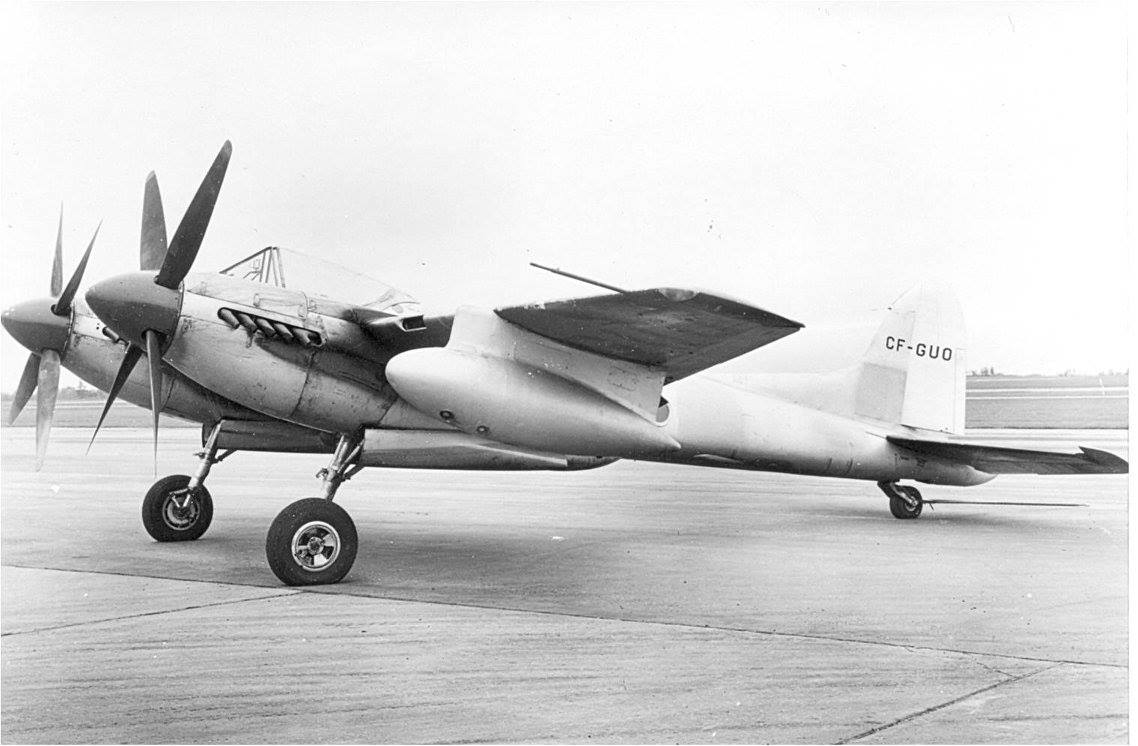

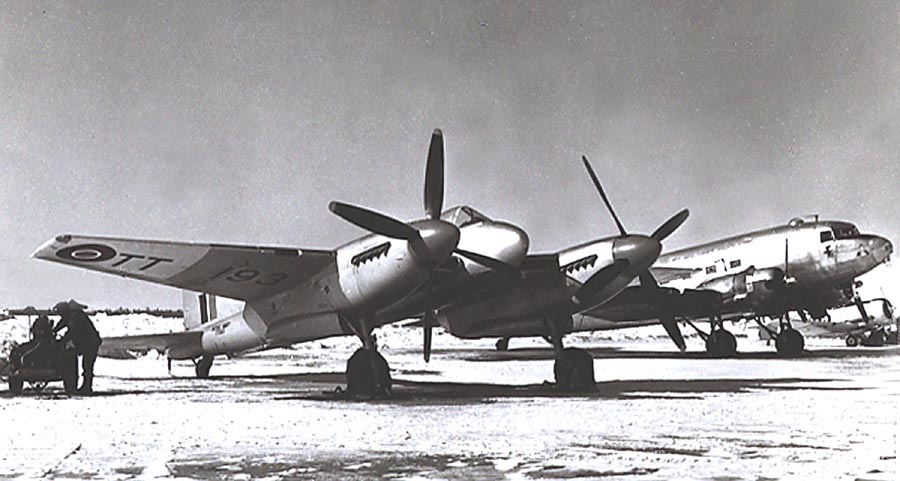

Just one Sea Hornet made it into civilian hands. This was F.20 TT193, which the Air Ministry sent to the RCAF Winter Weather Experimental Establishment in Edmonton, Alberta for cold weather trials in December, 1948. Following testing, the aircraft was surplus to requirements, and sold off to save the cost of shipping it home. Pilot William ‘Bill’ Ferderber registered the Sea Hornet as CF-GUO in April 1951, before selling it to aerial survey firm Spartan Air Services of Ottawa two months later. Ferderber flew it on a handful of high-altitude photographic missions for Spartan. However Spartan, presumably realizing they couldn’t easily get spare parts or additional examples, ended up trading the exotic aircraft to Kenting Aviation Ltd. for a pair of P-38 Lightnings soon after. These Lightnings were actually F-5Gs 44-26761/CF-GKE and 44-53184/CF-GKH. While ‘GKE was airworthy (and now with Kermit Weeks in Florida), ‘GKH took a year to fix corrosion issues before flying again, only to crash in the Yukon at the end of July, 1953.

Canadian aviation historian Robert M. Stitt, in communication with the author, noted that “the Sea Hornet was not the best or safest option for high-level photography, and that an exchange with Kenting was the way to go.” Aerial mapping work, in those days, was really a two-man job at a minimum, requiring both a pilot and a navigator/camera operator. In the case of the Sea Hornet, the camera operator had to slide backwards over the main spar carry through in the fuselage to reach his cramped station. During takeoff and landing, he lay on his belly on the main spar, holding onto a “grab bar” behind the pilot to give himself the illusion of an escape option should it prove necessary! Also, Stitt noted, “the pilot would have to do the navigation while keeping the aircraft straight and level at a precise altitude during photography while pressure-breathing oxygen and trying to read or create maps in a cramped cockpit; a huge workload and strain. So, it was far from ideal for either crew member.” Stitt suspects that Spartan would never have acquired the Sea Hornet had Ferderber not acquired it first, which is a fair point.

TT193 didn’t fly with Kenting for long. She suffered an in-flight failure of her port engine on July 11th, 1952. Her pilot, T.E. Bach, guided her safely in to a forced landing at Terrace Airport in Terrace, British Columbia. Kenting, being unable to fix the Sea Hornet, abandoned her in place and the airframe became a child’s plaything. Left to the elements and ‘little fingers’, the airframe deteriorated and eventually the airport manager had it carted to the local dump.

Sometime in the 1970s, an enterprising individual and his son recovered what remained of TT193. Richard de Boer noted the remains in outdoor storage on George Le May’s farm in Acme, near Calgary Alberta in 1979, and took the following photographs on a subsequent visit in 1990. Le May moved the parts under cover soon after. What you can see in these images is essentially the wing center section extending out to the wing fold. While much of the wood has deteriorated badly, there are many crucial metal parts in excellent condition, not to mention pattern examples for wooden parts as well. In addition to what is shown in these images, there are other significant parts in the collection as well. It may not look much right now, but other than Bob Jens’ B.35 VR796, the Mosquitos currently flying looked little better than this when they first started.

Pioneer Aero are collaborating with several others in addition to Aerowood on this project. This includes world DH.103 authority, David Collins. David Collins, based in the UK, has spent the last two decades scouring the world for Hornet parts and drawings. He has amassed a considerable amount of original material, plus many cockpit items unique to the type. Along the way he has also built cockpit replicas for both the Hornet and Sea Hornet, which include many original parts. You can see some of what he has achieved HERE.

The team also has 6,000+ factory drawings for the Hornet, and that coupled with Aerowood’s wealth of experience building the complex wooden structures for de Havilland Mosquitos. Like the DH.98 Mosquito, the DH.103 also had a moulded plywood fuselage. Believe it or not, one of these fuselage moulds still exists, albeit in poor condition, at the de Havilland Aircraft Museum in London Colney, England. The museum boasts three fully restored Mosquitos, including the prototype, but also has the rear fuselages of Sea Hornet NF.21s VX250 and VW957 on display. Perhaps more importantly, they have examples of the super-rare 130 series Rolls Royce Merlin from a Hornet on display. In fact, the most difficult part of this entire project will likely involve locating the right and left-hand turning Merlin engines specific to the breed (133/134). The Sea Hornet was the only aircraft to use these engines. Pioneer Aero are more than up to the challenge though, and resurrecting the Sea Hornet will be a crowning achievement for this impressive company. We must congratulate Pioneer Aero and their partners for taking on this singularly significant project, and cannot wait to see the results of their work to resurrect this long-extinct breed!

WarbirdsNews would like to thank Richard de Boer very much for the use of his photographs, and to noted aviation historian Robert M. Stitt for his details on Spartan Air Services, a subject in which he specializes. Richard de Boer is heavily involved with the Calgary Mosquito Society, which is restoring ex-Spartan Air Services Mosquito RS700/CF-HMS to its former glory when flying with the company. Please click HERE for their website, their YouTube channel HERE or the Facebook Page HERE. To see more of what Robert M. Stitt has been working on concerning Spartan Air Services, or if you can help with his research, please click HERE.

Wow this will be an epic restoration! good luck on an hard job, hope I get to see the restore.

Very nice, hope to see it finished

best of luck for this most ambitious project

So very Happy that someone has the courage (meaning everyone that is involved with the D.H.Hornet restoration that this graceful bird will eventually claim the clouds .I am presently trying to acquire accurate information on the short career of the Fleet Air Arm Aerobatic team in 1948.

The Last Hornet, resurrecting one of a kind, is the front runner of the resurrection of many.

Well done.

Amazing that so many iconic British fighters were extipated totally by their

parent services, & that even so, such rare parts from them – still exist!

Will anyone cobble together a Spiteful from Spitfire/Attacker parts?

Or a Sabre-Fury from a US radial powered example?

Perhaps the ‘handed’ Packard Merlins from a P/F-82 Twin Mustang,

could be utilized for this Hornet?

Best prop plane ever!

Can’t wait to see it in the air.

Good luck.

This is a very good Idea.

I think Captain Eric “Winkle” Brown would approve too.

Which aircraft had longer nacelles, the DH Mosquito or DH Hornet? Thanks

Fantasy Project – De Havilland Hornet mated to a pair of Rolls Royce Crecy engines.

I was a rigger working on Venoms at KaiTak in 1955-1957 and missed the Hornets by a few months. There was a scrap yard on the drome with plenty of the squadron there. I hitched a lift on our hanger tractor to see these aircraft but the driver left me behind when I popped into

a hut to phone the control for a green to cross the main runway !!

I’m a lover of the hurricane and mosquito, my favourite planes but to see a hornet in the air doing airshows wow!!!!

My 102 yr old father flew RAF Hornets in UK, Singapore and Honk Kong and will be very please to hear that this fantastic aircraft will be restored.

Any updates on the status of the DH Hornet ?

Hello Frank, good question! We just reached out to Pioneer and requested for an update. Cheers