By Cap Cordina

Few things in vintage aviation are as tragic as a restoration attempt gone wrong. Although the story of the B-29 Superfortress Kee Bird ended in heartbreak, its story, from the unprecedented rescue of its crew and the restoration attempt 47 years later is nothing short of extraordinary.

The Boeing B-29 Superfortresses were built during WWII as high-altitude, long-range bombers. They are credited for ending the war in the pacific, and it was a B-29 that dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Kee Bird, however, was different. After sitting in storage for a year, it was assigned to the 46th Reconnaissance Squadron for long-range photo-reconnaissance work, fitted with cameras and extra fuel tanks in the unused bomb trays. With the goal of mapping northern Greenland and searching for Soviet activity in the area, Kee Bird also completed weather studies, developed accurate polar navigation and also tested equipment and men in the polar environment during its seven missions.

The last flight

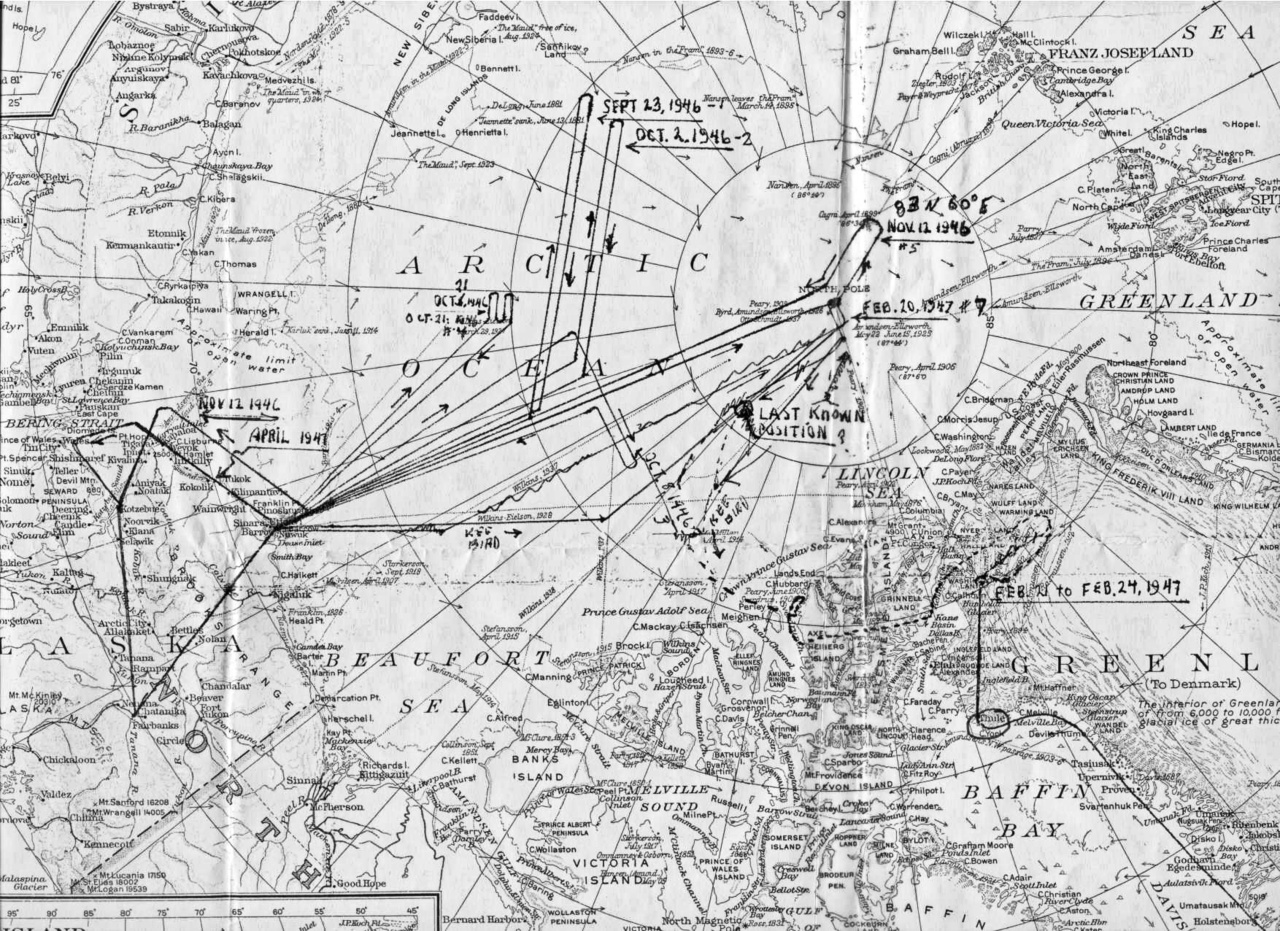

On February 20th, 1947, Kee Bird took off for its final mission: fly to the geographic north pole, then return through Ladd Field, a trip lasting 12-20 hours. It carried enough fuel to last 26 hours and had 11 men aboard. At around 8 am Alaska Standard Time on February 21st, the Point Barrow CAA Radio Station picked up calls from Kee Bird stating that they had hit a storm, were lost, and only had 4 minutes of fuel remaining and would thus be making a crash landing on land or ice. A rescue of this scale had never been attempted before, not when the distance between the crash and the nearest base was so great, or the weather conditions so brutal. But thanks to the determination of the United States Air Force, the excellent pilot who was able to land the Kee Bird on the frozen lake, and the crew’s survival skills, the men were found three days later relatively unharmed, and were taken to Westover Field, Massachusetts on February 24th by a C-54 transport aircraft. Kee Bird was marked as lost and abandoned in the Arctic by the Air force.

The Restoration

Key Bird remained there untouched for 39 years until 1985 when a British pilot spotted it and brought it back to light. It was found that the aircraft was still in great shape, and in 1994, the rights to its restoration were sold to a group operating as Kee Bird LLC, led by Darryl Greenamyer. It was decided that repairs would be made to achieve flying conditions then it would be ferried to Thule Air Base, Greenland, where the rest of the repairs could be made. The team used a 1962 De Havilland Caribou as a shuttle and over summer 1994, they brought in new engines, new propellers and tires. The team was able to replace all the components and fix up the control surfaces.

Then tragedy struck, and as winter began to settle on the site, the chief engineer, Rick Kriege fell ill and passed away from a blood clot two weeks later. Following the loss and the worsening weather, the team decided to leave the site for the winter. They came back a year later, in May 1995 to finish the repairs and head to Thule AB. They prepared a crude runway on the lake and Greenamyer began taxiing. Tragedy struck again, and smoke was spotted near the tail section. The crew’s attempts to extinguish the fire were unsuccessful, and they were forced to abandon Kee Bird and watch in devastation as it went up in smoke. The cause was estimated to be from the auxiliary power unit, which is used to provide power to start the engine. It most likely started leaking gasoline during the taxi, which ignited the fire.

There is always irony in tragedy, and in this case, it was the crew’s decision to convert the fuel system to injection to mitigate the risk of a fire, which was a known issue with B-29s. The Kee Bird’s fate resulted in not only the loss of the million dollar 3-year mission and the death of a crew member, but also the loss of important and beloved history. And a painful reminder of the fragility of historical preservation.

Surviving B-29s

If successful, Kee Bird would have been the third of remaining flyable B-29s. The others, FIFI and Doc, still fly around, attend air shows and offer rides to aviation enthusiasts around North America. FIFI, currently based at Dallas Executive Airport, started its career as an administrative aircraft in 1945, then retired in 1958 before being sold to the Commemorative Air Force in order to preserve history and teach lessons about the war. FIFI tours North America annually, participates in air shows and offers rides. It’s also appeared in multiple films in the 80s and 90s.

Doc, owned by Doc’s Friends, Inc. and based in Wichita, Kansas, was built in 1944. It did not see combat and was instead converted into a radar calibration aircraft, where it was named after the character Doc from Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. It was then used as a target tug, then ballistic missile target. The restorations began in 1998 after being traded with a restored B-25 Mitchell bomber and flew for the first time in 61 years on July 17, 2016. Since then, it’s appeared at various air shows, including EAA AirVenture Oshkosh, along with FIFI.

It is terribly sad that Kee Bird was lost a second time, probably permanently. The attempt was valiant and well intentioned. Bad luck all around. Of course the B-29 was a temperamental aircraft even when young.

Go for it again. It’s not like it’s at the bottom of the ocean like the Titanic. It’s reachable by investors who simply want to retrieve it and not fly it out of there in rough conditions.

Fellas, a’s, there is really NOTHING left salvageable after the fire which if you watch the recovery video you would know.

I was in one The beginnings of Doc, there was initial ground work to go recover the engines and maybe some other items depending

I just want to say that was devastating to watch and what a punch line, (punch in the gut!), ending to the documentary. Truly a roller-coaster of a story of the restoring, re-fitting of rebuilt engines etc to get her airborn again.

I have a cooy of the recovery documentary, a very well done piece of film. Does anyone know where l can find it on DVD? Also, in these comments, it was mentioned another film of going back to her??? Would that be available some where???!! Truly an amazing story.

God bless the awesome mechanic who literally worked himself to sickness and then death….. He is truly blessed for his dedication to that project and, also, all the other dedicated, compationate people involved and an integral piece of the whole story…….