(Image Credit: Victoria Air Maintenance, Ltd.)

In the comments section for our recent story on the first flight of the world’s only flying Mosquito, Warbirds News reader Paul Smith, tipped us off about another Mosquito that will soon be returning to the air. In a long-running restoration effort the crew at Victoria Air Maintenance, Ltd. in North Saanich, near Victoria, British Columbia have gotten a de Havilland Mosquito whipped into shape in preparation for a return to the skies over western Canada.

Mosquito from a helicopter, earlier this year.

While not as famous as some of the other allied aircraft of the second world war, the Mosquito is perhaps for Britons the most important plane of the war, at least according to a recent BBC Channel 4 UK documentary “The Plane that Saved Britain,” which just aired and included a film crew pilgrimage to Virginia Beach to the Military Aviation Museum to film the sole airworthy Mosquito in action. The documentary asserts that while the Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane are remembered as the machines that saved Britain from Nazi invasion in the Battle of Britain, and the Avro Lancaster and Handley Page Halifax are revered as the bombers that took the fight to the enemy, the greatest British aircraft of World War II was the less-appreciated Mosquito, which served with distinction as a fighter, a bomber, a U-boat hunter and a night fighter as well as a reconnaissance plane and a pathfinder for large scale bombing runs.

The two man plane’s greatest attribute, it’s speed, was a result of its unique construction, born from the wartime need to conserve metals which were in short supply, leading to a plane largely constructed from wood. The Mosquito’s fuselage was crafted in workshops turned over from furniture and cabinet-making from spruce, birch, balsa and plywood, were then put together with glue. The resultant plane was one of the fastest planes in the world when it entered production in 1941.

(Image Credit: Victoria Air Maintenance, Ltd.)

Its wood construction provided it’s greatest strength during the war, but was also its Achilles’ heel. While metal aircraft endured after the war, Mosquitos rotted away, between the wood decomposing and the loss of adhesion of the animal-based glues that held the plywood together, few Mosquitos survived long and very few remained airworthy to display on the air show circuits of the world, which caused the plane to fall to an undeserved level of obscurity. In fact, in interviews relating to the Military Aviation Museum’s Mosquito, Yagen stated it was the extreme challenge of the restoration and the lack of survivors that inspired him to take on the project in the first place.

(Image Credit: Calgary Mosquito Society)

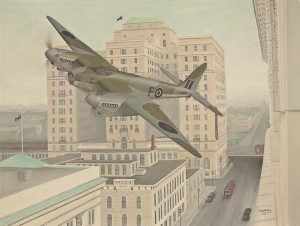

Without a doubt one of the most beautiful planes of the era, the end of the war saw them come home with the air forces that campaigned them, notably the Royal Canadian Air Force. One particular plane, Mosquito LR503, known as “F for Freddie,” late of 105 Squadron and survivor of 213 operations over occupied Europe, more operational sorties than any other allied bomber during World War II, captured the imagination of the Canadian public. Flown by combat decorated heros, the plane performed in a war bonds tour of Canada, famously performing an astounding aerobatic demonstration over (and through) Calgary on May 9, 1945 in celebration of the war’s end in Europe, shooting under low bridges and buzzing down avenues below building roof height. RCAF staff working on the sixth floor of the Hudson Bay building recall having to look down to see the Mosquito streaking past below their windows at over 300MPH.

(Image Credit: Victoria Air Maintenance, Ltd.)

The day after its famous buzzing of Calgary, the Mossie and her crew were scheduled to make flights over Penhold, Alberta, 80 miles to the north, then south to the RCAF bases at Lethbridge and Medicine Hat, before returning to Calgary for the night. During a series of extremely low and fast buzzes of the control tower at Calgary at the beginning of the day that saw the plane flying straight for the tower at near 400MPH at a level below the observation windows, and pulling up at the last possible moment, the plane struck the steel anemometer tower and flag pole atop the control tower, severing the Mosquito’s port wing and horizontal stabilizer from the airplane. The upward angle and high speed carried “Freddie” and its crew over the surrounding buildings and into a field almost half a mile from the terminal building. The plane struck ground at a shallow angle and exploded into flames, trailing wreckage and igniting the grass for over 300 yards and killing her crew.

(Image Credit: Victoria Air Maintenance, Ltd.)

Starting from just a shell and assorted components, the crew at Victoria Air Maintenance have painstakingly created a working Mosquito, wearing the markings and colors of “F for Freddie” in honor of the accomplished plane and her heroic crew of Maurice Briggs and John C. Baker, who after distinguished wartime flying careers tragically met their end on the home front. The plane, now with freshly-rebuilt Rolls-Royce Merlin engines installed, major systems in place and paint work in progress, should be returning to the skies soon, the world’s second flying de Havilland Mosquito.

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.

That is brilliant to see. Congratulations for all those involved. Now we need a home based one again.

Tremendous planning , focus, preparation, and passion.

Great going folks

I was consulted about handling KA114

I look forward to your completion.

If you need any handling stuff, please Email me.

i’m also affiliated with The peoples Mosquito Project.

Cheers

George Stewart

Looking forward to seeing this bird take to the air. Congrats on a terrific restore.

On May 8th,1945, Grant Miller and I rode our bikes to a hill in South Calgary and watched “F” for Freddie break every Air Reg in the book, with a beautiful display of extreme low flying. The next night, we went to the same hill, as we were told “F” for Freddie would do it again. We were used to Harvards, Ansons, Cessna Cranes and the odd Hurricane, but we had never seen anything so fast and so beautiful. The Calgary Airport was at least 5 miles North of our location. As we waited in eager anticipation, we saw a sudden plume of black smoke in the vicinity of the airport. We waited for half an hour but “F” for Freddie did not appear. We could only assumed the plane had crashed. The entire city was in mourning. It was an extremely sad event. I was thrilled to learn “F” for Freddie will fly again. The Mosquito is a beautiful aircraft. Congratulations. I now live in Vancouver. I hope to see it fly again. Dan Lemieux

I was in 436 RCAF Squdron on detachment near Sagan, Burma when a squadon of Mosquitoes arrived. We were to move them with our DC3s to Singapore. But in the two days we had to organize, the war was over and I was tour expired. So although we had talked to the aircrew and began organization for the move, an RAF squadron replaced us as we flew our own a/c back to Britain. The pilots said that it was great to fly them but in the tropics, at no more than 45 degrees of bank and then only if the termites held hands as the animal glue either got eaten or absorbed too much monsoon moisture to hold. They were in the middle of Burma which is wheat not rice growing as it gets only 30 inches of rain even in the monsoon season, so they could stay a while outside a hangar.

Wonder how long it will be before we see one in the air over her land of birth!

Fantastic stuff!

Only one in the world flying, and this will make two.

Well done and congrats to all involved in this important restoration.

My father flew mossies in 418 squadron, and i would be so thrilled to see it in flight, when do you envisage it coming to Vancouver?

Not sure Bryan, check with them: http://www.vicair.net/

I live in Saanichton, B,C, next to YYJ. I can confirm that F-for Freddie flew both yesterday, June 16, and today, June 17. I attended the airport at 11 am and watched as the crew fueled her up, fired the engines, taxied to 090, and soared into the air over Sidney, B,C. She did 2 circuits of the airfield before touching down to the roar of an admiring crowd. Today, as I worked in the garden, the syncronized sound of the twin Merlins brougt a tear to my eyes as she came through the valley. Congratulations to the staff at VAM for a job well done. Cheers, Jack.

I was visiting family at North Sannich near the Victoria airport. I could not believe my ears and eyes when I first heard the unique sound of the Merlin engines, then to see the Mossie flying.

Great job restoration crews.

If you guys have pictures please send them over.

I too watched That beautiful bird got yesterday and today. I live Right off the hanger. Great work, I Hope to see more of her.

David

WarbirdsNews,

Please go to the Victoria Air Maintenance Facebook page for pictures of the flight. https://www.facebook.com/VicAirMtnc/timeline

Thank you Marv, we have seen those pictures. Unfortunately they won’t let us use them.

Hi, My mother was ground staff on Photo reconnaissance during WW2 for a Mosquito squadron and my father was an observer for 618 squadron, mosquitos and part of the task group sent out to the Pacific area to attack the Japanese fleet. Father died of old age recently but mother is still going, but always wanted to fly in a DH Mosquito. Any possibility, even one circuit and bump??

Thanks for writing in David. Your parents both sound like they have/had some fascinating experiences in their lives. As for a flight for your mother, it never hurts to ask. There are only two airworthy examples in the world… the one owned and flown by Jerry Yagen’s Military Aviation Museum in Pungo, Virginia, and another owned by Bob Jens in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. I would suggest contacting them to see if you can arrange something.