Article by Peter Macca via rockdalecitizen.com

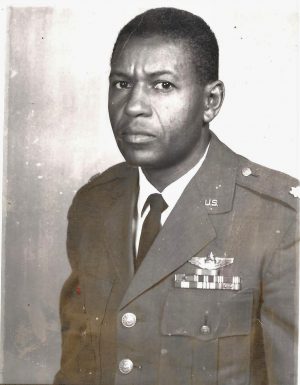

Slip on the flight suit of one of the first USAF African-American B-47 and B-52 pilots. Put on your helmet for the next mission over Vietnam with an all-white crew, then pin on the silver oak leaves of a lieutenant colonel after a lifelong struggle for recognition and approval. And be sure to buckle your seat belt because this story is one heck of a ride.West Virginia native Edgar Lewis joined the newly formed United States Air Force on July 13, 1949. “To this day I can’t tell you why I chose to get into airplanes,” he recalled. “I had never even seen one.” Asked if he meant to say “never inside of one,” Lewis replied, “No, I’m serious. I’d never seen an airplane until I joined the Air Force.”

After high school Lewis attended Hampton Institute, the historically all black university in Hampton, Va. Founded in 1868 to provide a higher education for freedmen, Hampton also accepted Cheyenne, Comanche, Kiowa, and other Plains Indians from 1875 to 1923.

Lewis complained about the racial incident. Instead of addressing the problem, a major took the easy way out and tagged Lewis as a “trouble-maker,” then transferred him to Ellington AFB near Houston. Lewis said, “They didn’t want me either, but a B-47 program was cranking up with a new navigation system and they needed candidates for that. So, I got shipped to Long Island, N.Y., to attend a private civilian training program on the new B-47 electronic system.”

Lewis spent four months training at Long Island before being sent straight back to Ellington AFB. “That didn’t make sense because they didn’t have B-47s at Ellington,” he said. “Therefore, I received orders for a base in Wichita, McConnell AFB, to work on the new B-47 electronic system. I was there about a year before deciding I needed to make a big decision concerning my career. I’d been on the WWII era B-29s and noticed the pilots and thought …. shoot, I can do that. So I applied for training as a pilot. They tested me again, which was really no big deal since I’d been tested all my life, and I passed those tests, too.”

His next port-of-call was Marana AFB in Arizona. “My primary training as a pilot was in the T-6 Texan. It was a good plane, but to me a little stupid to start people in it, but I survived,” he said. “The thing I remember most about finishing primary is going to Davis-Monthan AFB in Tucson to fly T-28s. My class was designated 53 Foxtrot. In 2003, 50 years later, I found out that I hadn’t been invited to the graduation ceremony. The ceremony was held in downtown Tucson. Two African-Americans in a class of 120, and neither of us were invited to our own graduation.”

But the training, and flying, and service to country continued. At Craig AFB Lewis flew the Lockheed T33 Shooting Star jet fighter. At Selfridge AFB, MI Lewis found himself behind the controls of the legendary F-86 Sabre Jet of Korean War renown. He mentioned, “I was the first black pilot to fly jets out of there.”

Lewis paused a moment. “You know, it’s difficult to explain, but some things in the military have changed, some haven’t. And our country is still addressing problems we had 50 years ago, but until we choose to attack the issues and solve them then, well, it could be our own demise. We still must try to understand each other; to work with each other.”

Familiarity with a B-47’s navigation system and his piloting skills earned Lewis a seat behind the controls of a B-47. “I still recall my first ride on a B-47 with a new crew, three of us, pilot, copilot, and navigator,” he said. “After we landed my copilot came to me and said, ‘Sir, you’ll have to find a new copilot.’ When I asked why, he replied, ‘Sir, my wife is from Selma, Ala., and I don’t think she wants me flying with you.’ I told him as far as I was concerned, he was my copilot, but if he wanted to change, then go do it.”

At home, Lewis told his wife about the copilot’s reluctance to fly with a black pilot. “You know what she told me?” he asked. “She said, ‘Invite them to dinner.’ I couldn’t believe it, but that’s what I did. Well, as fate would have it, my wife and his wife really hit it off. He stayed on as my copilot with no more problems.”

Eventually reassigned to a base in Kansas, Lewis rebelled. “At that base my wife and family would have to live down by the railroad tracks, not with other officers and their families. We weren’t going through that again, so I tendered my resignation.”

The Air Force refused his resignation. Instead, Lewis accepted orders to Lockbourne AFB in Ohio to continue flying the B-47. “I wasn’t there too long before my commander called me in and said that 8th Air Force had the new B-52 Strategic bombers. They’d never had an African-American B-52 commander, and the Air Force wanted me to go. That’s how I got into the BUFs (Big Ugly … Fellows). The B-52 is an awesome weapon, but it’s clumsy and you had better stay ahead of the aircraft because if you get behind it, it’s difficult to catch up.”

All his training, practice and more practice, fighting the controls while fighting injustice, now came to fruition. From Kadena AFB in Okinawa, Anderson AFB, Guam, and U-Tapao AFB in Thailand, Major Edgar Lewis flew 226 combat missions over Vietnam. On his missions: “We didn’t go into North Vietnam, not yet, so our missions were in South Vietnam or reasonable facsimile. Sometimes we didn’t know the target, just the coordinates. We were fortunate, only two bad incidents that I recall. We lost an engine on one mission during midair refueling. That can be a bit touchy, but we completed our mission with one engine out. On another we lost our heating system. That, too, was a bit touchy.”

Lt. Colonel Edgar Lewis served 23 years in the Air Force, then served 22 years with the FAA. Asked to choose his favorite aircraft, Lewis replied, “I didn’t have one. But if forced to choose, I’d say the B-47. To tell you the truth, we did some pretty stupid things in that aircraft, like pulling an Immelmann. (A half loop followed by a half roll, resulting in level flight in the opposite direction). We lost some guys doing that, pulling straight up in a B-47. The stress could pull the wings off.”

His final thoughts on an Air Force career: “Even with the racial issues, I enjoyed my Air Force career. Truthfully, there was no other profession I could have gone into during that time that would have afforded me the opportunities that I was given. I think every American should have to go through some type of military training, if not for a career, then to learn discipline. For some of us the military was the only discipline we ever received. I brag about it … people say, well, the military trained you well … and I say, no, I had to train myself.”

Article by Peter Macca via rockdalecitizen.com

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran. For story consideration or comments: [email protected]

To read Pete’s stories visit www.aveteransstory.us

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.

We need to hold a graduation in Tucson!

An amazing story of an amazing man! I lift my hat to Lt. Colonel Edgar Lewis. And what a smart wife of his.

I was a 2nd Lt 54F grad Mar 1954. Lackland, Kinston, Webb. Sent to Randolph B-29 transition Apr – Jul, then to B-47 unit at March AFB Aug 1954. My total flying hours were about 350. This was considered to low to even be a B-47 co-pilot with all the WE I I recalls with thousands of hours. SAC changed policy and I got my own B-47 crew in Jul 58 at transition class at Forbes AFB. AC, NAV both 1Lts, CP 2 Lt. Flew B-47 for ten years from March and Hunter with thousands of days standing nuclear loaded alert around world, Cal, Alaska, Guam, Morocco, Spain, Georgia. Agree, mostly a great life.

What a great man. I would be proud to serve under his command. In 1992 I was in The 34 BS at Castle AFB. I was lucky to have served under Commander Rice. He too was a great African American B52

pilot and Air Force Academy Grad. We need men, heroes and all around great guys like you two in the Air Force. I home school my children and I will definetly use the history of injustice to never giving up. Thank you and God Bless you.

From an Air Force Vet, I served during 72 to 79 and as long as the brothers stayed on the ground or in the pacs seats we were ok, I was an Aircraft electrician for 3.5 years and decided to crosstrain to flight engineer C5A, wow what a mistake,being from Baltimore,Md I had never experience racism before but the second I got to flight school I knew something was wrong,I was never wanted,my answers were always wrong and they said the same thing and they were right,several time a white student would make a mistake and later I discovered I was blamed.Its still the same old crap why why get over it all of us bleed red blood and we are all Americans on the same side,I guess those folk will never learn untill their backs are up against the wall just like 2008 and no one will help.