The Planes of Fame Air Museum’s Mitsubishi ‘Zero’ is an A6M5 Model 52, perhaps the most effective variant of the type. The Nakajima Aircraft Company (Nakajima Hikoki Kabushiki Kaisha) produced this example, under license, as construction number 5357 in May of 1943. Bearing the tail code 61-120, the fighter served in the Imperial Japanese Navy with the 261st Kōkūtai (Air Group), a unit sometimes referred to as the Tiger Corps, beginning in July of 1943. While with the 261st Kōkūtai, the aircraft initially took part in defending the Japanese Home Islands (namely Honshu), then Iwo Jima (from October 1943 to March 1944), and finally Saipan (from Aslito Airfield).

Photo via San Diego Air & Space Museum Archives

Saipan, being part of the Mariana Islands, was once a Spanish colony. The United States gained control of the island following the Spanish-American War of 1898, but soon sold it to the German Empire. At the onset of WWI, however, Imperial Japan, then on the Allied side, invaded Saipan and wrested control from Germany. The League of Nations formally approved Japan’s ownership in 1919, which prompted Japanese settlement and the expansion of population centers. Japan considered their defense of the Marianas to be of vital importance in 1944, not only because of the Japanese civilian population in the islands but also because they knew the airfield facilities on Saipan and other islands in the Marianas, such as Guam and Tinian, could provide a lethal launching point for American heavy bomber raids against the Japanese homeland. Up until that point, American B-29s could reach Japan only from the rough airfields in Southern China, a far more dangerous route considering the numerous Japanese air defenses along the way. The Marianas’ strategic importance to Japan thus ensured that their fight to maintain control would be even more ferocious than for more distant islands, such as Guadalcanal and Tarawa. Despite their determined resistance, however, Japan’s military machine was a shadow of its former self in 1944 and could not withstand the numerically and technically superior onslaught from the United States Army, Navy, and Marines.

When the 27th Infantry Division secured Aslito Airfield on June 18th, 1944, 61-120 was among a group of eleven A6Ms and a lone Nakajima B5N2 “Kate” torpedo bomber captured intact. American personnel loaded the aircraft aboard the escort carrier USS Copahee (CVE 12), which then set sail for San Diego, California, arriving on July 28th, 1944. At Naval Air Station North Island, a technical team inspected and performed maintenance on 61-120 (which included a repaint). They then approved the aircraft for flight testing; it performed its first flight in the US on August 5th. On August 22nd, a ferry pilot flew the Zero to NAS Anacostia in Maryland on the outskirts of Washington, DC. On the following day, Commander Fitzhugh L. Palmer (a Navy Cross recipient for actions during Operation Torch) flew the fighter on the remaining short hop to the Technical Air Intelligence Center (TAIC) at NAS Patuxent River in coastal Maryland. The U.S. Navy re-designated 61-120 as TAIC 5 during its time under flight testing.

On September 6th, 1944, U.S. Navy test pilot Clyde Cecil Andrews took TAIC 5 up on the first of his seventeen test flights in the aircraft, which totaled 21.5 flight hours in all. From October 16-23, 1944, TAIC 5 was the only Axis aircraft flown during the Fighter Conference held at NAS Patuxent River, which saw the Zero’s performance being evaluated against the F4U, FG-1, and XF2G-1 Corsair, F6F Hellcat, FM-2 Wildcat, Supermarine Seafire, F7F Tigercat, XF8F-1 Bearcat, YP-59A Airacomet, P-61 Black Widow, P-47 Thunderbolt, P-63 Kingcobra, de Havilland Mosquito, Fairey Firefly and P-38 Lightning. On the final day of the Conference (October 23), Andrews checked out Charles Lindbergh in TAIC 5; Lindbergh was a test pilot for the United Aircraft Corporation at the time. His signature remains in the aircraft’s logbook to this day. Other pilots who flew TAIC 5 during the Fighter Conference include Grumman test pilot Corwin Henry “Corky” Meyer, who later became the President of Grumman from 1974 to his retirement from the company in 1978, Bell test pilot Jack Woolams, who would later go on to become the first pilot to fly the X-1 supersonic research aircraft, and McDonnell test pilot Edwin Woodward “Woody” Burke, who soon after conducted the first flight of the FH-1 Phantom jet fighter in January of 1945.

After completing its trials at Patuxent River, it was flown back to Anacostia on November 30, 1944. A week later, on December 6, the aircraft returned to NAS North Island in San Diego, where the aircraft was flown against newly-trained naval aviators about to be deployed to the Pacific Theater, in order to acquaint them with the handling characteristics of the Zero. The primary test pilot for the aircraft at North Island was William N. Leonard, another Navy Cross recipient, this time for actions at Tulagi in preparation for the Battle of the Coral Sea, who would later go on to be a Rear Admiral in the Navy. Two of his flights in TAIC 5 were affiliation exercises flown against a Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer patrol bomber, held on March 19 and 20, 1945 respectively. With Victory in Japan declared on August 15 and the formal surrender ceremonies held in Tokyo Bay on September 2, TAIC 5 was flown to NAS Alameda, California, and declared surplus to Navy requirements after logging over 190 hours of flight time.

Sold as surplus by the U.S. Navy, TAIC 5 was acquired by Edward T. Maloney, a young aircraft collector from southern California who had dreams of creating his own air museum, the first dedicated museum of its kind west of the Mississippi. On January 12, 1957, The Air Museum would be opened to the public in a former lumberyard on Foothill Blvd (part of Route 66) in the city of Claremont, California. It was also during this time that 61-120 began being used in the production of several war films and television shows, such as the 1959 film Never So Few, along with the museum’s airworthy Nakajima Ki-84 Hayate. With the addition of more and more aircraft, the museum in Claremont no longer had sufficient display space, and the museum would move three more times, first to Ontario Airport, then to Buena Park as part of the Cars of the Stars and Planes of Fame Museum, and finally to Chino Airport as the Planes of Fame after the flyable aircraft had already been in Chino by this point.

In 1973, museum founder Ed Maloney and museum pilot Don Lykins were in Japan to participate in the Japan International Aerospace Show, conducting the flight demonstrations of the last remaining Nakajima Ki-84 Hayate, now displayed at the Chiran Peace Museum, when they met the president of Mitsubishi Aircraft. He had learned of the Planes of Fame and asked if the museum had a Zero in the collection. After Maloney and Lykins replied yes indeed, there was a Zero in the museum, the president then asked “Can you make it fly?” They responded that it would take time and money, but when Maloney and Lykins returned, they were determined to restore 61-120 to fly again. It would be the first Zero to fly since the 1940s. Sourcing for funds from both the U.S. and Japan was limited, but every time it was said that the Zero could not fly again, it made the museum’s staff more determined to complete the process. To assist in the restoration, Maloney and other museum officials were able to get materials from the archives of the Smithsonian, the Air Force Museum, the San Diego Aerospace Museum, and even Jiro Horokoshi, the Zero’s designer who was still alive at the time, all of which provided insightful information to the restoration. In November of 1977, 61-120’s overhauled Sakae engine was run up for the first time in the restoration. Final assembly was overseen by Jim Maloney and Steve Hinton. The two pilots also installed new wiring and overhauled the hydraulic and electrical systems. By mid-1978, the Zero was ready for its first test flight. By this point, Ed Maloney had begun collaborating with the Zero Flies over Japan Committee, which was established by Mr. Hiroaki Kato for the purpose of bringing the Zero back to Japan for a series of flight demonstrations. Kato had assembled a film crew at Chino Airport to record the first flight, in which, on June 28, 1978, Don Lykins took off from Chino, accompanied by Jim Maloney flying chase in the museum’s P-51D Mustang 45-11582. Lykins tested the Zero for over an hour before landing back at Chino and declaring the aircraft to be in perfect condition. Two more test flights were conducted that day, first by Jim Maloney and then by Steve Hinton. After Lykins, Maloney, and Hinton completed the test flights, the Zero was deemed ready for shipment. On July 10, it was flown to Long Beach Airport for its first U.S. press conference. The next morning, it was transported to San Pedro, the Port of Los Angeles, and housed aboard the Nissan car carrier Laurel, where a temporary wooden hangar was built on the deck around the aircraft, which was transported in one piece, and wrapped in multiple layers of plastic to keep out the sea spray and prevent as much corrosion as possible. After all precautions to protect the Zero on the voyage to Tokyo were completed, the Laurel set to steam, set to arrive in time for the first flight in Japan to coincide on August 15, 1978. When the Laurel arrived in Tokyo, the Zero was hoisted onto a barge and towed to Japanese Ground Self-Defence Force (JGSDF) Kisarazu, which had been a naval air base for the Imperial Japanese Navy during WWII. Over the next six months, the Zero toured Japan to much fanfare, attracting many surviving Zero pilots, such as Saburo Sakai, and young people in Japan who had heard and read about the Zero, but had never seen one in person, let alone see one fly. The aircraft also received a new paint scheme, replicating the scheme the aircraft wore on Iwo Jima before being transferred to Saipan. A total of four pilots flew the Zero over Japan: Don Lykins, Jim Maloney, Steve Hinton, and John Muszala. Eventually, the Zero was shipped back to the United States to rejoin the rest of the Planes of Fame’s collection.

Zero Over Japan, as narrated by Edward T. Maloney

Given the rarity of its original Nakajima Sakae radial engine, the museum adopted a policy of flying the aircraft only for special occasions, such as the annual airshows in Chino, or one of the museum’s monthly flying days held on the first Saturday of the month. The Zero was usually reserved for the December event to commemorate the attack on Pearl Harbor. In 1995, to mark the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II, 61-120 returned to Japan for yet another flying tour, this time accompanied by P-51D 44-73053 “Wee Willy II.” Once again, the tour was well-received, with model kit company Hasegawa even issuing a commemorative 1/72 kit to build both aircraft.

By this point, other Zeros, mostly recovered from abandoned airfields in the South Pacific, had been restored to static display in various museums around the world. Several Zeros were restored to flying condition, though these flyable examples are considered by some to be replicas with a few original parts and data plates installed. What helped 61-120 retain a unique reputation in the warbird community was due to the wrecks either possessed corroded Sakae engines that could not be returned to working order or lacked engines altogether when found in situ. All other flyable Zeros were restored utilizing American Pratt & Whitney R-1830 radial engines, with cowlings slightly modified to account for the slightly larger size of the engine was still the only flyable A6M Zero to retain an operational Sakae engine, and was the only flyable Zero that was captured intact and flight tested by the United States during WWII. In 2000, it was flown in the production of the film Pearl Harbor, along with some of the recently restored Pratt & Whitney-equipped Zeros. Though the fictional love triangle in the story weighs the film down, along with certain historical inaccuracies littered within, it should be noted nonetheless that aside from using dark green paint schemes not used until later in the Pacific War, it can be appreciated that original Zeros were used in the production, though converted Vultee BT-13s and -15s still had to fill in for the Aichi D3A “Vals” and converted T-6 Texan/Harvard filled in for Nakajima B5N “Kates.” Given the lack of operational examples, this is certainly understandable. In the years after the film was released, the sight of 61-120 flying in formation with the Commemorative Air Force SoCal Wing’s A6M3 Model 22 X-133 and A6M3 Model 22 AI-112 (now flying with the Fagen Fighters WWII Museum in Granite Falls, Minnesota) was common at Chino during the annual airshow. After the production of Pearl Harbor was completed and the movie released, the Zero’s movie paint gave way to the original tail code of 61-120, but three victory marks were added to the lower portions of the tail. It was in this guise that the Zero would remain for the next decade.

In 2012, 61-120 made its latest visit back to Japan. However, it would not make another flight tour around the country. Instead, it was displayed for a year at the Tokorozawa Aviation Museum, one of the country’s premier aviation museums, situated on the spot where Japan’s first airfield once stood, and from where Yoshitoshi Tokugawa made the first flight of an airplane in Japan on December 19, 1910, flying an imported Farman III. The Zero was displayed as a special exhibit for a year before returning to the United States in 2013, but not before a public demonstration at the museum where Planes of Fame pilot John Maloney, son of Ed Maloney and brother of the late Jim Maloney, got into the cockpit and ran the engine of the aircraft. Among those gathered was Kaname Harada, an A6M Zero pilot who had provided cover for the Japanese carrier fleet during the attack on Pearl Harbor, fought at the Battle of Midway, and later in the Solomon Islands before ending the war as a flight instructor. After the war, Harada became the principal of a kindergarten that he and his wife ran together and even became an anti-war activist after seeing Japanese youth compare news footage of the Gulf War in 1991 to fireworks displays. Harada spoke about his wartime experiences and impressions of flying the Zero but also urged those gathered to remember the war for the casualties, both in the Pacific Theater and on the Japanese home front, in order to never go to war again.

Upon returning from Japan, 61-120 would undergo a complete overhaul, the most extensive one since its restoration to flight in 1978. During the three years from 2013 to 2016 that saw 61-120 stripped down, reassembled, and repainted, Vultee BT-15 42-42171, having been converted to resemble an Aichi D3A Val for the film Tora! Tora! Tora!, and later used in Pearl Harbor, was brought up from the museum’s Valle, Arizona location, just south of the Grand Canyon, and flown in the Zero’s place until 61-120 could return to the air. When it emerged for its post-overhaul flights, 61-120 sported a new paint scheme, based on a photograph of the aircraft taken at Aslito Airfield on Saipan in 1944. Today, 61-120 continues to make the occasional demonstration flight, but outside these flights, it can be found on display in the museum’s Foreign Hangar in Chino, surrounded mostly by German and Japanese aircraft of WWII. For some visitors, such as those from Japan, it is the primary reason for visiting the museum, and is certainly a highlight for every visitor with an interest in aviation history.

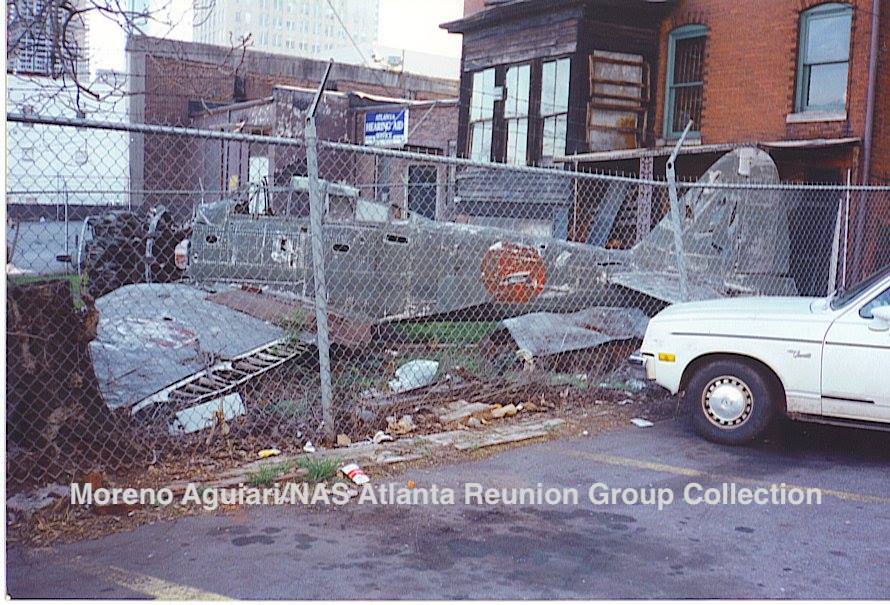

Interestingly, 61-120 is not the last remaining A6M5 captured at Aslito Airfield in 1944 but is one of three aircraft remaining. A6M5 Model 52 c/n 1303, tail code 61-121, was later evaluated as TAIC 11. Stripped to bare metal and with British national markings applied, it was set to be sent to the Allied Technical Air Intelligence Unit-South East Asia (ATAIU-SEA) in India. However, it remained in the United States and was repainted yet again with generic Japanese markings. In 1945, the aircraft ground-looped at NAS Atlanta, Georgia (now General Lucius D. Clay National Guard Center), and was set to be scrapped until it was acquired by James Hardee Elliott, Sr., who operated the Atlanta Museum in a Victorian-era brick house named for its first owner, Rufus M. Rose, in downtown Atlanta.

This private museum was later run by J.H. Elliott, Jr. The Zero was displayed wheels-up in the backyard of the house and exposed to the elements. Visitors were allowed to see the Zero for $2.00. Over the years, the Zero was advertised as being the Akutan Zero, the first Zero that was flight tested in the U.S., in spite of the fact that the Akutan Zero was, in fact, an A6M2 Model 21 variant and was shipped to San Diego from Akutan Island in the Aleutians in August of 1942, two years before 61-121 was even captured. When Elliott Jr. died in 1989, the assets of the museum were sold off, including A6M5 61-121, which was acquired by R.D. Whittington of World Jet Inc. in Fort Lauderdale, Florida between 1991 and 1992. Originally intent on restoring the aircraft, he found its condition to be beyond his resources to restore, so he stored it until he sold the aircraft in 2001 to Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen. It would later become part of the Flying Heritage and Combat Armor Museum. Allen registered the aircraft as N1303, but also kept it in storage until placing it on display in unrestored condition until the pandemic of 2020 closed the museum to the public. During the period between the closure of the museum and the acquisition of the majority of its assets by Stewart Walton, c/n 1303 was listed and sold off to a private owner, who has yet to disclose any photos or information publicly.

The other remaining Zero from Aslito is c/n 4340. Its exact tail number is disputed, but it is believed to be either 61-106 or 61-108. Regardless, it was coded as TAIC 7 before being transferred to the US Army Air Force at Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio, and redesignated FE-130 (later T2-130). It also received the name Tokyo Rose for its cowling. In addition to being flight tested at Wright Field, it was evaluated alongside other foreign aircraft from both Allied and Axis nations at Freeman Field in Seymour, Indiana. It was at Freeman that T2-130 and several of the other aircraft were shipped to a former C-54 plant at Park Ridge, a suburb of Chicago that would become home to O’Hare International Airport, to be accepted into the Smithsonian’s National Air Museum. When the Korean War necessitated the Air Force to use the facilities at Park Ridge, the aircraft in storage were shipped to a new storage facility near Washington, D.C. named Silver Hill, which would later be named for the Air and Space Museum’s first curator, Paul E. Garber. When the museum’s downtown DC location was being prepared for its grand opening in 1976, 4340 was painted in the markings of tail code 61-131, and displayed in the museum’s WWII in the Air gallery. Due to ongoing renovations at the museum, 4340 is currently being kept in storage, but will likely return to display in the coming years.

Most combat veterans will tell you that surviving warfare is a combination of having the right skills, being in the right place at the right time, and simple “good luck.” This is equally true for aircraft which have survived past conflicts. Planes of Fame’s Mitsubishi A6M5 “Zero”, which will feature in Saturday’s “Flying Demo”, is one such example of a combat aircraft that survived WWII due to its technology, the skill of its pilots, and simple good fortune. The museum’s David Willis will walk visitors through this naval fighter plane’s unique history – from its manufacture through to its preservation by Planes of Fame. Along the way, you’ll see the role that good timing and luck played in the survival of this very rare aircraft. For more information about this event click HERE.

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.