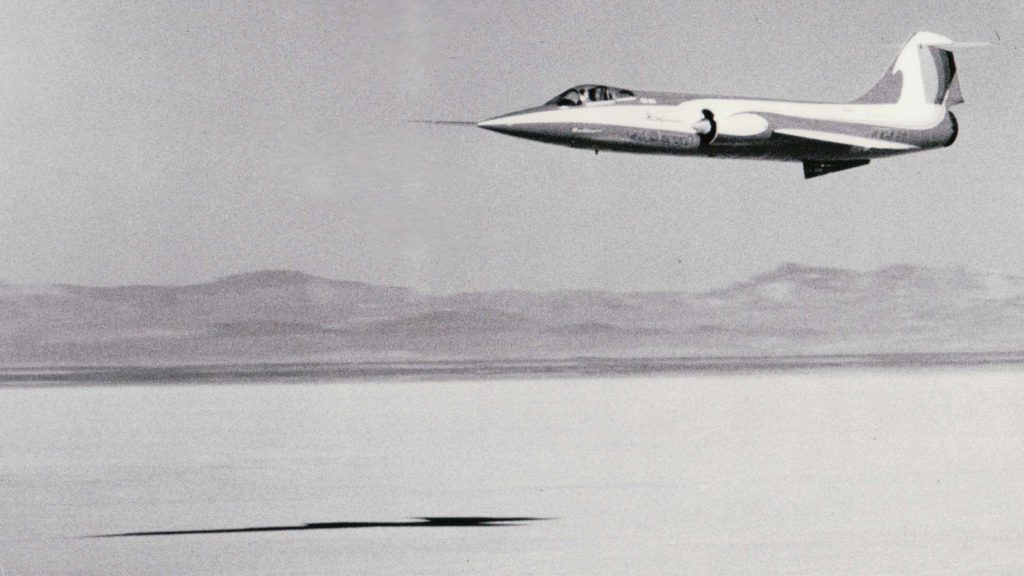

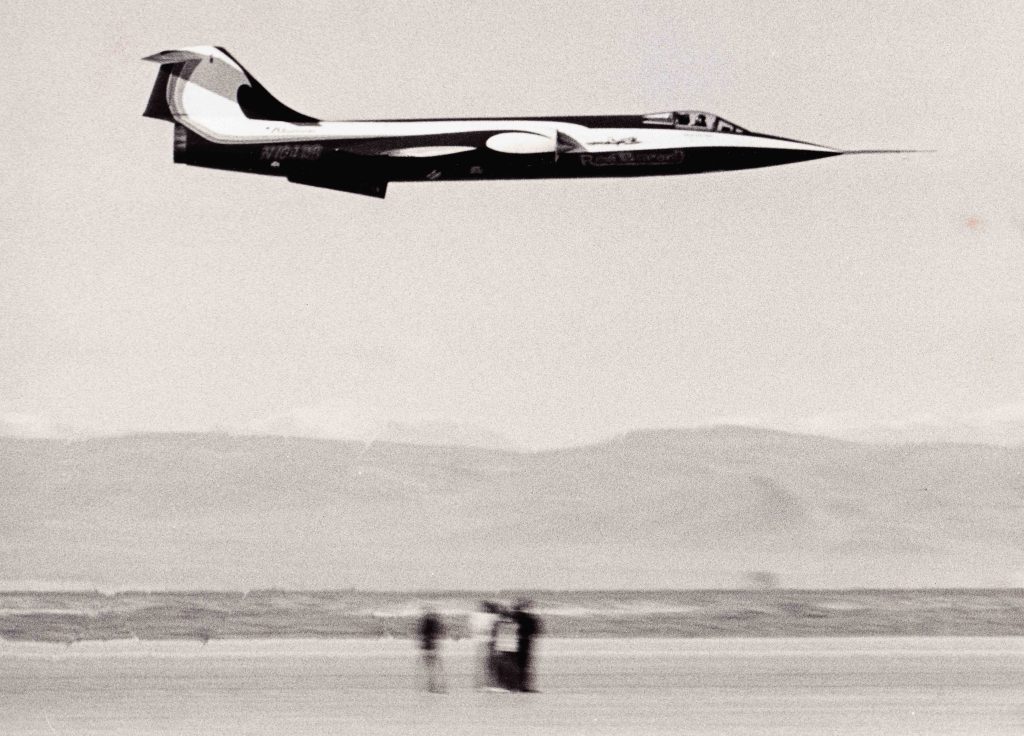

IT WAS LIKE WATCHING A GHOST. IT MOVED SO FAST THAT EVERYTHING ELSE STOOD STILL BY COMPARISON. THE RED AND WHITE JET WENT BY WITHOUT A SOUND. IMPOSSIBLE. IT WAS SO CLOSE, SO FAST, SO LARGE, AND SO SILENT IT DEFIED YOUR SENSIBILITY. AS YOU STOOD THERE, STUNNED BY THE FRIGHTENING SIGHT OF THE SPECTER YOU HAD JUST SEEN, A GIANT FIST REACHED OUT OF THE SKY AND PUNCHED YOU IN THE CHEST. YOU COULD FEEL THE SHARP CRACK IN YOUR HEART. – Aviation News, November 1977

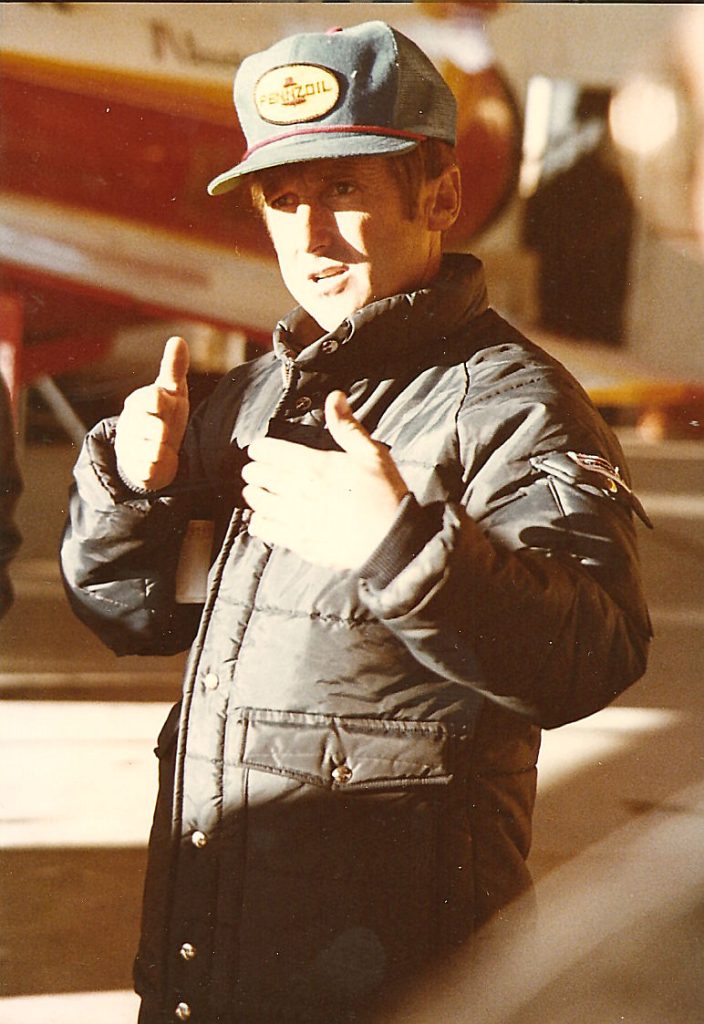

The name Darryl Greenamyer has always been synonymous with speed. He flew F-86As and F-100As in the Arizona Air National Guard until 1960 when he was hired by Lockheed as an F-104 production test pilot. In 1963, he attended the United States Air Force Aerospace Research Pilots School at Edwards AFB, California. When Lockheed moved F-104 production out of Palmdale and he was laid off, but immediately hired by Lou Schalk, Chief Test Pilot for Advanced Development Projects, better known as The Skunk Works. Darryl became just the 13th pilot to check out in the A-12 and over the next 11 years he made numerous experimental and development test flights in the A-12 and SR-71.

And of course, most Vintage Aviation News readers are well aware of Darryl Greenamyer’s success at Reno where in his eleven years of Unlimited competition he won seven National Championships, not to mention the 3Km World Speed Record in 1969, at the controls of the famous #1 Bearcat. However, amid all of that success, the record that Darryl was most proud of was the one he set in his hybrid RB-104 Starfighter known as the Red Baron.

On April 28, 1961, Soviet pilot Giorgii Mosolov set a world altitude record of 113,891 feet in a Mikoyan-Gurevich Ye-66, an experimental MiG-21. This did not sit well with Darryl, and he started making plans to use an F-104 to take that record away from the Communists. However, there were two problems. First was getting an F-104. In the 1960s it was impossible for a civilian to purchase a complete Starfighter, so in 1965 Darryl began collecting F-104 parts to build his own. The second problem was funding, because everything in aviation, especially world record attempts, takes money. Just like the famous quote from The Right Stuff “No bucks. No Buck Rogers,” Darryl says, “I thought if I used the airplane to break the 3km speed record held by the Navy, I could raise a sponsor for the altitude record.” At the time the low-altitude 3km Closed Course Speed Record was 902.769mph, which was set on August 28, 1961, by USN Lieutenants Huntington Hardisty and Earl De Esch in a McDonnell Douglas F4H-1 Phantom during Project Sageburner.

Darryl’s hybrid F-104 was registered as N104RB and carried the Lockheed construction number of an F-104G. However, it had built from literally dozens of F-104s of all variants. The tail section, minus horizontal stabilizer, came from a crashed TF-104G that was found in an Ontario, California junkyard. The horizontal stabilizer came from a wrecked F-104G. He obtained the forward fuselage of a discarded F-104A that Lockheed used for static testing. The cockpit side panels came from the first production F-104A that crashed in 1956. The throttle quadrant came from an aviation enthusiast in Tennessee who had been using the part as an office decoration.

Attracted by the mystique of ‘the project,’ Darryl’s mini Skunk Works team soon read like a Who’s Who of Aerospace Engineering: Bob Allen, Jim Black, Bruce Boland, Roger Davies, Phil Greenberg, Bob Hariston, Pete Law, Ben McAvoy, and Randy Scoville, plus various Lockheed and NASA employees working off the clock. Although he would assault the speed record first, the project team made altitude-record-specific modifications during construction. A water injection system was fitted in the inlets to lower the operating temperature and increase the operational redline of the General Electric J79-GE-10 engine. On the opposite end of the engine, a nitrous oxide system was installed in the afterburner section. The most notable modification was the installation of a Reaction Control System (RCS) similar to that on the rocket-assisted NF-104 Aerospace Trainer. This would help Darryl control the F-104 in the thin air above 100,000 feet, where aerodynamic flight controls would be less effective. Darryl recently talked about these and other modifications made to the aircraft. “I took out whatever I did not need in order to save weight, but I added extra fuel tanks to the gun and electronic bays. I needed the extra tanks because making four consecutive speed runs inan afterburner used a lot of fuel. I removed the two forward fuel pumps in the main fuel tank because in the altitude attempt when I’d kick the airplane up, the fuel would go to the pumps in the back of the tank.” The latter modification would cause Darryl a brief problem during a 1976 practice run, but more on that later.

Throughout the decade-long construction, Darryl searched for an engine, and it would eventually take him all the way to the Pentagon in the spring of 1976. “A friend of mine was vice-president of an aerospace firm,” Darryl explained. “He had some friends in the Pentagon and suggested we go see if the Air Force would loan me an engine. I was looking for an F-4-spec J79 because it put out a little more power than the J79 in the F-104. So I went to the Pentagon, walked into this room full of Air Force Generals, and made my presentation. They said, ‘Are you kidding? Get out of here.’ So I went down the hall to the Navy with the same presentation. Not only did they agree to loan me an engine, but they also gave me a contact at NAS North Island in San Diego, where they apparently overhauled the engines. I called North Island, and they said they had five engines just out of overhaul and told me to come down, pick the one I wanted, and they’d put it on the engine stand and show me where and how to tweak it to get more power.”

As America’s Bicentennial approached, Ed Browning, owner of the Idaho-based Red Baron Flying Service, came on board to provide Darryl with much-needed financial and logistical support. Browning’s sponsorship also gave the F-104 its name, “Red Baron.” In August, the Starfighter was gently loaded onto a flatbed and trucked to Browning’s hangar in Idaho Falls, where the J79 was installed. When flight tests began in September, it was clear that the Red Baron was a formidable performer. Its empty weight of 11,500 pounds was 3,400 pounds less than the Aeritalia F-104S- the penultimate version of the Starfighter. Even with 1,100 gallons of fuel, the 18,000-pound thrust J79-GE-10 engine gave the Red Baron a thrust-to-weight ratio greater than 1:1, better than any fighter of the day, including the F-15 Eagle.

To be specific, Darryl was attempting to break the Class C-1, Group III, low altitude jet speed record, which required an ‘unaugmented’ (no rocket assist) jet-powered aircraft to make four consecutive passes, two in each direction, along a straight, 3-km (1.86 miles) course at or below 100 meters (328 feet). On the turnaround,s Darryl would not be allowed to climb higher than 500 meters (1,640 feet). At either end of the course, a pair of 16mm Photo-Sonics Model 16-1PL high-speed cameras with 75mm lenses and electronic clocks were surveyed perpendicular and 3,000 feet south of the course.

On October 2 & 3, 1976, the Red Baron team descended on Mud Lake, a dry lakebed 30 miles south of Tonopah, Nevada to take on the Navy speed record. On Sunday, October 3, Darryl made four blistering passes through the course with one clocked at 1,030mph! His four-run average was 1,010mph, 108mph faster than the Phantom—a new speed record seemed to be in the bag. Then the team got word that that one of the timing cameras had malfunctioned and a positive image of the aircraft could not be established. The film was sent to several labs for analysis, but in December Darryl was notified that his record would remain unofficial. Undeterred, Darryl would try again in 1977.

On October 24, 1977, shortly after 1100 hrs, timing and photographic personnel, crewmembers, and spectators were all in place out in the middle of the lake bed. It was completely and utterly silent. At 1120 hrs, the silence was broken when voices of spotters up in the hills crackled on the radio, “Here he comes!” Cameras and timers were switched on as everyone squinted towards the eastern horizon. In the 2012 interview,w former Air Classics writer Bruce Treadway told the author, “I have never seen anybody fly an airplane like Darryl flew that F-104. To this day, I don’t know how he did it. He was so precise and smooth run after run. My camper was parked in the middle of the course to help give Darryl a depth perception. I watched the runs from the roof. I would pick him up in the distance as he approached the lakebed, seconds later he zipped over my head. By the time I turned around he was out of sight! The ground really shook when the sonic boom hit. The whole run took just seconds. The speed was absolutely stunning. It was hard to comprehend. After he’d passed, I noticed the shockwave had sucked dust into the air. I could not see it as he approached, and it cannot be seen in photographs, but I could see and smell it as it hung in the air for a few minutes.”

Darryl’s four runs were clocked at 976.969, 985.578, 999.971, and 990.524mph for an average of 988.260mph. To help put this speed in perspective, it took Darryl an averageof 6.791 seconds to travel the 1.86 miles between the timing stations! On January 31, 1978, Darryl’s speed record was officially certified by the Federation Aeronautique International (FAI). Today, 36 years later, this supersonic speed record still stands.

Shortly after returning from Tonopah, Darryl began preparations to break the Soviet altitude record, which had been raised on August 31, 1977, when Alexander Fedotov flew a specially modified Mikoyan-Gurevich Ye-266M (MiG-25M) to a staggering 123,520 feet. To set a new record under FAI regulations, Darryl had to beat the Communist record by 3%. This meant he would now have to climb to over 128,000 feet! In developing the flight profile for the zoom climb, Darryl received valuable input from a former NF-104 pilot and Lockheed, who ran a computer study for him. They calculated that Darryl should accelerate to 2.5 Mach at 45,000 feet, engaging the water injection during acceleration. He would then initiate a 3G pull to a 60-degree climb angle. Darryl takes up the story: “By the time I initiated the climb, I’d already had the water injection on, and at a point in the climb, I would engage the nitrous oxide. This would boost the engine enough to put me over the top.”

The plan was solid, but as flight tests began, problems with the Red Baron arose almost immediately. First, a leak in the RCS was discovered, and repair was required. On his first flight to test the nitrous oxide system Darryl faced an in-flight emergency. “The nitrous oxide gets injected into the afterburner. I took off and flew around a bit, and when I engaged the burner, some of the fuel and heat from the exhaust backed up in the line from the nitrous oxide tank. So, when I pumped the nitrous oxide down there, it hit that hot spot and ignited. The explosion blew a hole in the side of the airplane. So we repaired that, and to prevent it from happening again, we installed a nitrogen flush system to flush the line out so the fuel would not come back up the line.”

On February 26, 1978, Darryl pointed the Red Baron into the crystalline skies over the Mojave Desert and climbed to 45,000 feet to test the water injection system. He engaged the afterburner and rapidly punched through the sonic barrier. As he approached 1.5 Mach, he engaged the water injection, and the Red Baron surged to 2.2 Mach. Thoroughly satisfied with the system, Darryl returned to Mojave Airport, made a quick fly-by, and entered the landing pattern. As he lowered the landing gear, he only got two green lights; the left main gear was not locked. Darryl climbed to altitude to troubleshoot the problem “I changed light bulbs while I tried to figure out the problem,” he said. “But nothing worked. I headed over to Edwards because they had emergency vehicles. I called Edwards Approach and notified them of my landing gear problem. To verify the gear was not locked, I made a gentle touch and go and felt the left landing gear collapsing. I climbed to 10,000 feet and asked the tower where the ejection area was, and they directed me to a bombing range to the east.”

Unlike many pilots, Darryl recalls the ejection in vivid detail. “I had never ejected from an airplane before. They say when you pull the handle and accelerate out of the airplane, you black out. Well, I indicated 210 knots when I ejected, and on my way out, I counted the rivets on the canopy bow. I didn’t black out at all and had my hand on the parachute handle in case the seat didn’t work, but it worked great. After I was under the chute, I started looking around for the airplane, figuring it would just nose in, but it continued flying east. It went out maybe 10 miles, made a big 180-degree turn, and started coming back towards me. It seemed to be coming down at the same speed I was. At one point, it looked like it was going to hit me, but it made a small turn to the right and went behind me. I quit worrying about that and started worrying about the landing, which went fine. I landed about a ¼ mile away from the airplane.”

When the Red Baron smashed into the desert floor, it took with it Darryl’s hopes of bringing the altitude record back to the United States. Whether or not Darryl could have taken his 104 to nearly 130,000 feet will forever remain a matter for conjecture. What is not up for debate is the Red Baron F-104 was, and still is the World’s Fastest Warbird.

I am in the picture of the 5 people as Darryl flies by. Asher Ward, Jack Ward (13), Dirk Williams, Tranina William Dirk’s Wife and myself Mark Williams. It was a spectacular day at Tonapah NV.

There really should be a movie made about this guy.

It should be called “Bold Pilots” Because there are Old Pilots and there are Bold Pilots and no one knows how this guy got old. Installs Nitrous in a Mach 2 Jet plane? It blows up with him flying it?

This is true, I am Mark’s brother. I help build the RB104 and was there in the picture.