At the center of this incident were two of the most important weapons in the arsenal of the United States military at the time: the Convair B-36 Peacemaker, the first American intercontinental bomber, and the Mark 4 nuclear bomb, the first atomic bomb built for mass production.

Originally designed as a contingency should the United States need a bomber that could have flown from the US East Coast to bomb Nazi Germany and return to the US without refueling, the Convair B-36 Peacemaker did not fly until 1946, one year after WWII ended. However, with the USA now locked in a Cold War with the Soviet Union, the B-36 could fly further and carry a heavier bombload than any other aircraft in the newly independent United States Air Force, making it the first intercontinental bomber in the USAF. The Mark 4 nuclear bomb was developed at the Los Alamos National Laboratory and based on the design of the Fat Man (Mark 3) bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. Like the Fat Man device, the Mark 4 was an air-dropped nuclear fission weapons that relied on a weaponeer to arm the bomb with a nuclear core by the weaponeer inside the bomb bay before it was to be dropped. Over 500 Mark 4 bombs would be built, and they entered service in 1949.

That same year, the aircraft involved in this incident rolled off the Convair production line at Fort Worth, Texas as a B-36B-15-CF, and was accepted into the USAF as serial number 44-92075, and was assigned to the 436th Bombardment Squadron, 7th Bombardment Wing at Carswell Air Force Base in Fort Worth as part of the USAF’s Strategic Air Command (SAC), and was distinguished by the buzz number 075 painted on its forward fuselage. By February 1950, however, the aircraft had been assigned to an exercise at Eielson Air Force Base near Fairbanks, Alaska, where conditions were freezing, and night reigned for nearly the entire day. On February 13, aircraft 075 was took off from Eielson on a long-range training mission, with pilot Captain Harold L. Berry and copilot Raymond P. Whitfield at the controls.

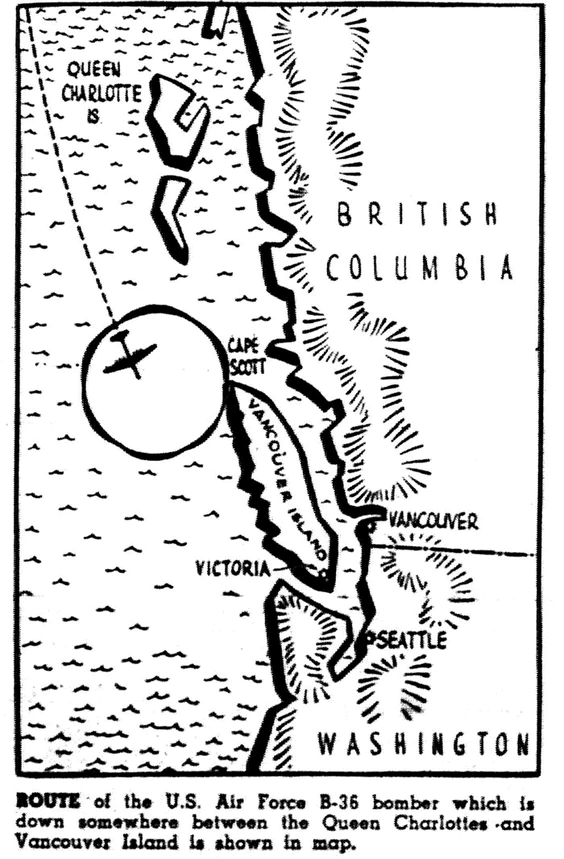

The mission parameters called for the aircraft to skirt the Pacific Northwest from the Alaskan Panhandle, past British Columbia, and then turn inland over Washington state to fly east before making a turn over Fort Peck, Montana to the southwest to make another turn over southern California in order to conduct a practice bombing raid against San Francisco, mimicking the speed, altitude, and heading they would use on a real mission except they would not release the Mark 4 bomb. Then, after covering nearly 5,600 miles nonstop in the air, they would return to Carswell. The 17-man flight crew was sent on this long mission to simulate the length-of-time flown during a potential nuclear strike against the Soviet Union.

Though the Peacemaker was not carrying the Mark 4’s plutonium core (as all genuine cores were under the custody of the US Atomic Energy Commission, and until 1951, needed the President’s approval to be transferred to the US military), it held a “dummy” core filled with lead for installation, which was carried in a lead-lined capsule nicknamed the birdcage, and the bomb itself had a substantial quantity of natural uranium and up to 5,000 lbs. of conventional explosives.

When B-36 44-92075 took off from Eielson, temperatures were at -40 °F (−40 °C), which was known to cause ice to build up not only on the wings but in the carburetor air intakes as well, which were placed forward of the rear-mounted, pusher configuration Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major radial engines. Another thing to note about this aircraft is that although the Peacemaker was later upgraded with the addition of four General Electric J47 turbojet engines, these had not been installed on 44-92075 by the time of the incident.

Seven hours into the flight, as aircraft 075 was attempting to reach and maintain its cruising altitude of 40,000 feet while carrying a full load of fuel, a 10,900-pound Mark 4 bomb, and being weighed down by ice on the wings, fuselage, engines, and tail, flying at an airspeed of less than 200 knots with engines at full power and running full rich. Just after midnight, flight engineer Ernest Cox reported fuel mixtures and intake icing.

Then, the #1 engine, the leftmost engine on the left wing caught fire and had to be feathered, followed by the #2, on the left wing’s center section, which also caught fire and was forced to be feathered, and then the #5 engine, the centrally mounted engine on the right wing burst into flames and had to be shut down. The aircraft was now flying on only half of its engines, and the crew radioed SAC headquarters at Offutt Air Force Base, near Lincoln, Nebraska of their predicament. Knowing their chances of survival in a bailout over the freezing northern Pacific were slim to none, Captain Berry and Lieutenant Whitfield decided to jettison the Mark 4 bomb in the Pacific Ocean, then guide the crippled Peacemaker to Princess Royal Island, British Columbia for the crew to bail out. The Peacemaker’s autopilot would then take the aircraft on a clockwise course away from land to crash into the Pacific. As the crew prepared to bail out, the Mark 4 nuclear bomb was released northwest of Princess Royal Island at an altitude of 9,000 feet (2,743 meters), and a barometric detonator was timed to destroy the bomb at 1,400 feet (427 meters). Several of the crewmen reported sighting a large explosion in the area where the bomb was reported to have been released.

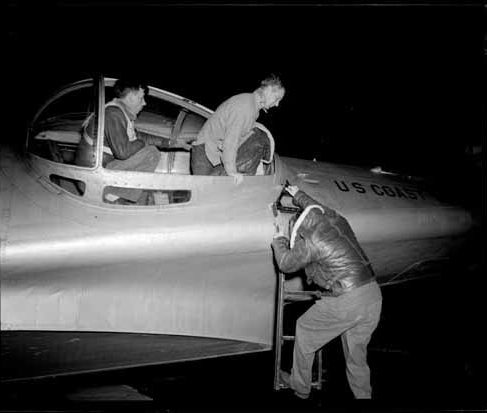

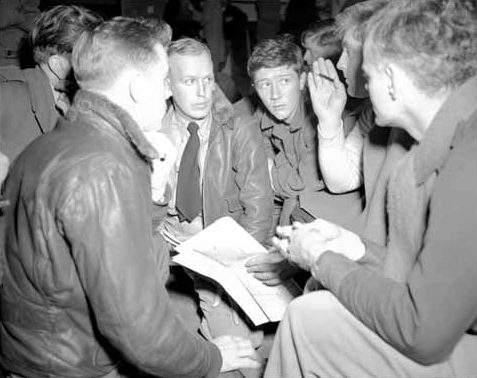

In the dead of winter and the dead of night, the 17 men of 44-92075 bailed from their B-36, with flames from the engines trailing back to the tail. They saw their bomber loop over them and the drone of its remaining engines disappearing into the cold February sky. Within minutes of receiving news of the incident, both the United States Air Force and the Royal Canadian Air Force set off on one of the largest search-and-rescue missions up to that point. They even recalled aircraft searching for a Douglas C-54 Skymaster transport that went missing three weeks earlier and remains to be found to this day. In the resultant search (in which the Canadians were not told of the nuclear weapon), 12 survivors were rescued by Canadian fisherman and military personnel and returned home in celebration. Yet five men would remain missing, including Captain Theodore “Ted” Schreier, the Peacemaker’s weaponeer.

A subsequent inquiry launched by SAC into what was both the first accidental loss of a nuclear weapon and the second loss of a B-36 since one crashed on takeoff at Carswell Air Force Base in 1949 determined that the cause of the onboard fires was the carburetors icing over, causing the engines to overheat. The five men reported missing were later presumed dead, and were believed to have parachuted unwittingly into the waters off Princess Royal Island and subsequently succumbed to hypothermia.

Two years later, in 1952, a fisherman found a parachute attached to a military-issue boot, which contained a male’s left foot. Though buried in a 1954 ceremony to honor the five missing airmen at the Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery in St. Louis, the remains were exhumed in 2001 after one of the daughters of the missing men persuaded the government to compare the DNA in the bones with those of the relatives of the five missing men. In 2012, the U.S. Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command confirmed the remains to be those of Staff Sergeant Elbert Pollard, a gunner on the B-36 that night in 1950, and S/Sgt Pollard’s remains were laid to rest under his own name at the San Francisco National Cemetery, with full military honors.

Yet three years later, the first Broken Arrow incident created a new mystery. While searching for a missing De Havilland Dove flown by Texas oil tycoon Ellis Hall, who went missing along with his wife, his two daughters and a family friend on August 17, 1953, a Royal Canadian Air Force search plane discovered the wreck of B-36B Peacemaker 44-92075 on August 20. Inexplicably, the aircraft whose autopilot had been set to fly out to sea and crash in the Pacific Ocean off the British Columbian coast had turned up intact on the icy slopes of Mount Kologet on the east side of the Kispiox Valley, over 200 miles north of the bailout point and 50 miles east of the Alaskan border.

As the aircraft still contained onboard systems that were still considered top secret, the USAF mounted an expedition to retrieve what they could from the downed Peacemaker and destroy what could not be retrieved. The team arrived in September 1953, but harsh weather conditions forced the USAF team to delay their mission to the following year. In August 1954, the USAF disposal team finally reached the crash site with the help of a local guide. After recovering what they could take back down the mountain with them, the team planted explosives to destroy B-36B 44-92075.

After a 1956 civilian survey noted the coordinates of the wreck, the crash site of the Peacemaker involved in the first Broken Arrow incident was undisturbed until an American and a Canadian expedition visited the site in 1997. Upon checking the radiation levels, they determined that the site did not have any levels higher than natural background radiation. Some items from the wreck, including one of the B-36’s remote-operated 20mm gun turrets, have gone on display at the Bulkley Valley Museum in Smithers, British Columbia.

Yet the first Broken Arrow incident has left some unanswered questions, with the biggest among them being: How did the Peacemaker fly a further 200 miles north of the bailout point, over mountainous terrain, to end up on Mount Kologet? The most commonly accepted theory goes that with the aircraft’s remaining engines at full power, combined with a northward gale blowing at 55 mph, the lessening of the aircraft onboard fuel from consumption by the engines, and possible de-icing due to drier conditions inland, the B-36 drifted on its own until it crashed on the mountain. Another theory, albeit unsubstantiated, posits the one of the missing crewmembers remained on the aircraft and guided it northwards until crashing on Mount Kologet. Proponents of this theory suggest that weaponeer Theodore Schreier, who had been trained as a pilot before becoming a weaponeer, remained onboard the crippled bomber after the rest of the crew had bailed out. However, no evidence exists in the declassified Air Force reports to suggest that any human remains were found at the crash site, and without evidence to prove the latter, then the former scenario remains the most likely, less dramatic, explanation unless new evidence can definitely prove or disprove it.

No matter the cause of the first Broken Arrow Incident, it represents the first time in which weapons powerful enough to destroy the world could be lost through accidents, and the crew of B-36B 44-92075 deserve to have their memory endure.

The crew of Convair B-36B Peacemaker s/n 44-92075

Survivors

Captain Harold L. Barry (Pilot)

1st Lt Raymond P. Whitfield (Co-pilot)

Lt Col Daniel V. MacDonald (AFSWP* bomb commander)

1st Lt Ernest O. Cox (Flight engineer)

1st Lt Charles G. Pooler (Engineer)

1st Lt Paul E. Gerhart (Navigator/radar operator)

1st Lt Roy R. Darrah (Observer/scanner)

S/Sgt James R. Ford (Radio operator)

S/Sgt Vitale Trippodi (Radio operator)

Cpl Richard J Schuler (Radio mechanic)

S/Sgt Martin B Stephens (Gunner)

S/Sgt Richard Thrasher (Gunner)

Missing

Captain William M Phillips (Navigator)

Captain Theodore F Schreier (AFSWP* weaponeer)

Lt Holie T Ascol (Bombardier)

S/Sgt Elbert W Pollard (Gunner; remains recovered in 1952, identified in 2012)

S/Sgt Neil A Straley (Gunner)

* Air Forces Special Weapons Project

Today in Aviation History is a series highlighting the achievements, innovations, and milestones that have shaped the skies. All the previous anniversaries are available HERE