On this day in aviation history, January 28, 1917, the Junkers J.I made its first flight. Developed as the J 4 by the Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works, the aircraft was accepted into the Imperial German Air Service (the Luftstreitkräfte) as the first all-metal airplane to enter combat and the first to be mass produced.

In 1915, the Junkers Company of Dessau, Germany, produced the world’s first all-metal aircraft, the J 1, which was followed by the first all-metal aircraft intended for military service, the J 2 in 1916 (though it never entered production or operational service). Junkers’ trials in all-metal designs caught the attention of the Inspectorate of the Air Troops (IdFlieg), which oversaw the procurement of military aircraft. In November 1916, the IdFlieg was looking for an “infantry aircraft” (ground attack aircraft) that could also be used for observation and liaison purposes. As part of this order, three companies (AEG, Albatros, and Junkers) responded with designs of their own, which resulted in the AEG J.I, the Albatros L 40 (which IdFlieg designated as the Albatros J.I), and the subject of today’s story, the Junkers J 4 (which the IdFlieg also designated as the Junkers J.I).

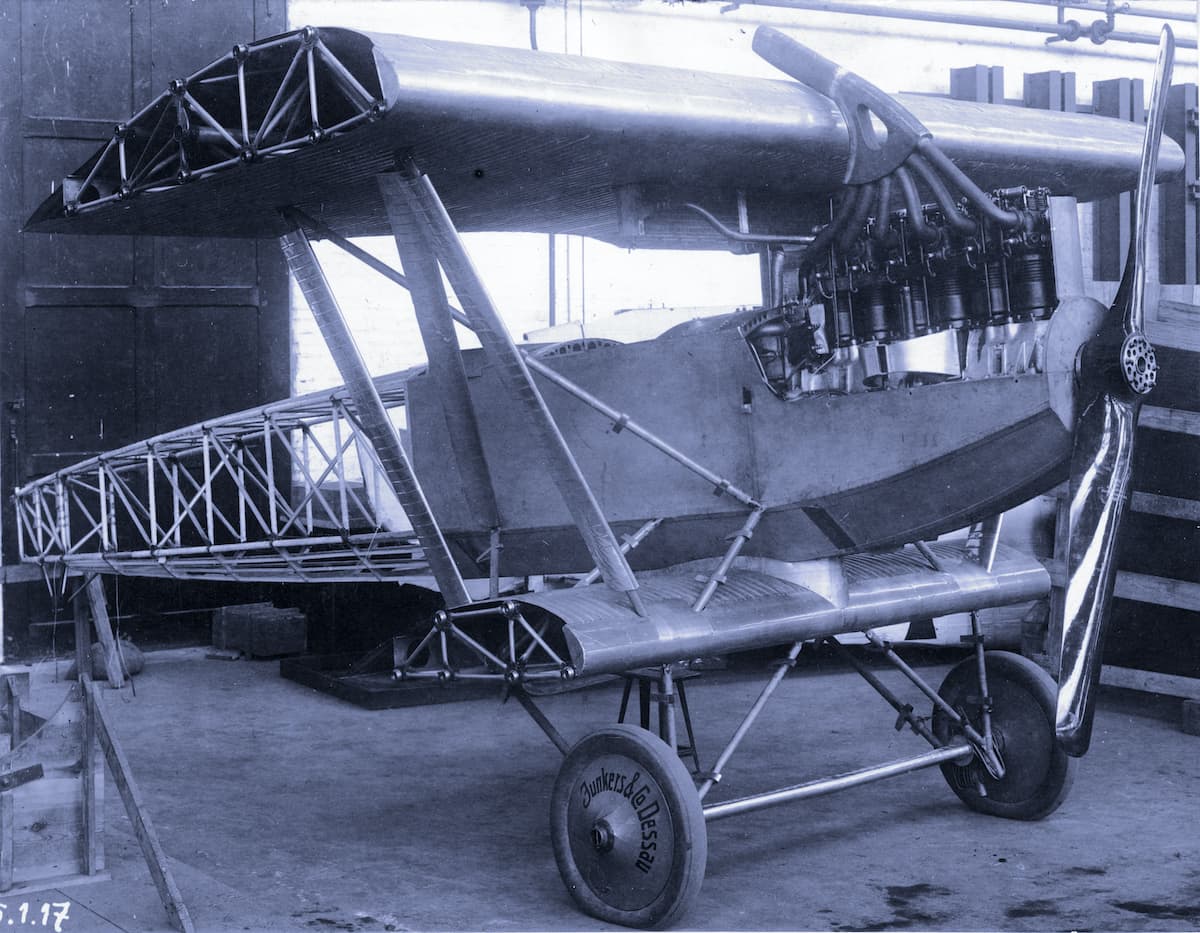

The Junkers entry, designed primarily by engineer Otto Mader, differed from the AEG and Albatros aircraft in that it was of all-metal construction (though some J 4s had fabric covering for the rear sections of their fuselages), while the two competitors were more conventional in that they were primarily of wood and fabric construction. The Junkers J.I had an armored “bathtub” compartment 5mm thick that housed the pilot, rear gunner/observer, fuel tanks, and the engine (a design element of later attack aircraft). Unlike the earlier J 1 and J 2 that were skinned in steel alloy, the J 4 featured corrugated duralumin skin for its wing and tail panels, with the corrugation adding strength to the lighter alloy. The aircraft was powered by a Benz Bz IV six-cylinder, water-cooled engine that produced 200 hp, and also differed in that it was a sesquiplane, a biplane where one set of wings (in this case the lower span) is significantly shorter and smaller than the other. Although it had supporting struts for the center sections of the wings, it had no bracing wires as seen on many contemporary aircraft of the period.

On January 17, 1917, the aircraft begin its test trials in Berlin, making its first flight on January 28, 1917, at the IdFlieg airfield in Döberitz, with test pilot Arved von Schmidt at the controls. The takeoff from the snowy field was long, even with the rear fuselage’s armor removed, as von Schmidt required 200 meters (656 feet) to take off, before reaching an altitude of 250 meters (820 feet), then landing after four minutes in the air. Schmidt described the aircraft as strongly tail-heavy due to the lack of armor, but otherwise stable to fly. After further modifications were made, the Aviation Inspectorate awarded Junkers with an order on February 19, 1917, to build 100 production aircraft, making the Junkers J 4/J.I the world’s first series-produced all-metal aircraft.

By the end of 1917 and the beginning of 1918, the first Junkers J.Is entered operational service with the German Air Service. Though Luftstreitkräfte pilots were at first skeptical of the performance of the slow, ungainly-looking aircraft, the durability of the design was self-evident. This applied not only to survival against small arms fire, but also to the Junkers’ ability to be placed out in the weather rather than have to be more out of hangars in the event of a rapid deployment. The Junkers J.I was also designed with shipping in mind, as the craft could be disassembled into six major components (wings, fuselage, landing gear, and tail) for transport by rail or road, and be reassembled and mad airworthy in the field by a team of six to eight groundcrew in four to six hours.

The Junkers J.I was deployed during the German spring offensive in 1918, Germany’s last gamble to defeat the British and the French before the new American forces arrived en masse. Attempts were made to fit the J.Is with downward-firing machine guns for ground attack but turned out to be of limited use because of the difficulty of aiming the fixed guns. Instead, the J.Is were mainly used for army liaison work and low-level reconnaissance, or airdrop ammunition and supplies to advancing German shock troops. Few if any Junkers J.Is were recorded to be destroyed by Entente air defenses, but issues in production meant that the Junkers J 4s were limited in number. Indeed, by the time Germany signed the Armistice that ended WWI on November 11, 1918, only 183 Junkers J.Is were produced. A further 44 were built between November 1918 until production halted in January 1919, leading to a total of 227 J 4s manufactured.

These were then quickly handed over to the victorious Allied Powers as war reparations and extensively studied for further development of all metal airplanes, but soon after the valuations were complete, nearly all of the remaining Junkers J 4/J.Is were scrapped.

There are, however, some exceptions, though. The fuselage of construction number 278, which was built in April 1918, was one of four J 4s transferred to Italy following WWI as war trophies. In 1973, the fuselage of 278 was acquired by the Museo Nazionale Scienza e Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci (Leonardo da Vinci National Museum of Science and Technology) in Milan, which had painted the serial 805/17 on the fuselage. In 2005, the aircraft was temporarily transferred to the Deutsches Technikmuseum in Berlin, Germany for restoration and short-term display before it returned to Italy in 2010 and is now part of the Italian Air Force Museum in Vigna di Valle, on the shores of Lake Bracciano.

Another J.I (construction number 252, IdFlieg number 586/18) is the last intact survivor. In 1919, it was sent to Canada as a war trophy for display at the Canadian National Exhibition held in Toronto in August 1919. After being held in storage, it was acquired by the Canadian Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa, where it is now on display in the museum’s WWI gallery.

Today in Aviation History is a series highlighting the achievements, innovations, and milestones that have shaped the skies. All the previous anniversaries are available HERE