This October, it was announced that a team of aviation mechanics and pilots who are part of the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA) intend to build a flying reproduction of a 1930s Curtiss Hawk II biplane fighter-bomber. However, while the Hawk II was more commonly associated with its service in the US navy as the F11C Goshawk and in the service of foreign air forces such as those of Bolivia, China, Colombia, Thailand, and Turkey, the Hawk which this team hopes to rebuild was associated with a German WWI flying ace who helped convince Hiter’s Luftwaffe to adopt dive bombing tactics, which would become one of the hallmarks of the German Blitzkrieg through Europe during the opening year of WWII.

The history that inspired the Curtiss Hawk II reproduction project harkens back to 1931, when Ernst Udet, Germany’s second-highest ranking ace of WWI (second only to the Red Baron, Manfred von Richthofen, whom Udet had served with as part of Jagdgeschwader 1), and its highest-scoring ace to survive the Great War, was attending the US National Air Races held in Cleveland, OH to perform his famous aerobatic routine in his U 12 Flamingo biplane, which had been constructed by an aircraft company he helped to found, Udet Flugzeugbau GmbH. After Germany’s defeat, Udet gained fame as one of the most daring and experienced aerobatic pilots in the world at that point. Despite the Flamingo’s moderate output of 125 hp on takeoff, Udet would perform death-defying stunts from “dead-stick” loops, landing at the exact point where he would take off, and even using the wing of his plane to pick up a handkerchief.

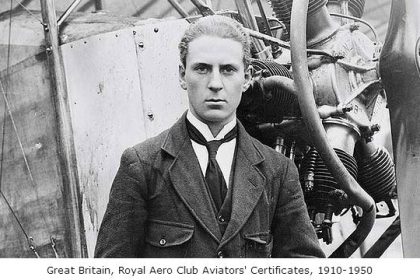

One airplane at the show stood out to Udet, though, and that was a Curtiss 1A Hawk, flown by former US naval aviator turned racing and aerobatic pilot Alford “Al” Williams. Williams’ Hawk had originally been flown by the Curtiss company as a demonstration aircraft. Udet was impressed with the performance of Williams’ Hawk, which was powered by a 700hp Wright Cyclone radial engine. However, at $20,000, Udet could not afford such a machine, and Willaims was sponsored at that time by SOHIO Oil, and after 1933 by Gulf Oil, with his Hawk becoming the famous Gulfhawk. However, although the Treaty of Versailles prohibited Germany from having its own air force, German engineers were still secretly drawing up plans and even conducting clandestine flight experiments in preparation for their reformed air force. The German military would not have long to wait for their air force, though, for when President Paul von Hindenburg appointed the firebrand Adolf Hitler to appease the latter’s vocal supporters, Hitler also brought in Udet’s former commanding officer and fellow WWI flying ace Hermann Göring, who also become the head of the newly formed Ministry of Aviation (Reichsluftfahrtministerium; RLM). Soon, Göring had some work in mind for his old comrade Ernst Udet, and an offer Udet couldn’t refuse.

Talented as a pilot Udet may have been, he was not one for managing things. His business Udet Flugzeugbau went bust, and its assets were acquired by Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (BFW), whose chief engineer Willy Messerschmitt would later rebrand BFW to his own name. Udet was also a well-known playboy and life-of-the-party, indulging in drink and women regularly, and was uninterested in politics up to that point. But in 1933, with Göring looking to build up the air arm that would become the Luftwaffe, he knew of Udet’s interest in the Curtiss Hawks, and that the Curtiss company in Buffalo, NY, was selling an export model of the US Navy’s F11C Goshawk, the Hawk II, that would offer everything Udet wanted. Göring promised that he would use the RLM’s funds to purchase two Curtiss Hawk IIs if Udet were to join the Nazi Party. Udet joined the Nazi Party on May 1, 1933, and by June he was back in America to observe flight tests involving the F11Cs. Udet eagerly reported his findings back to Göring and to the State Secretary of the RLM, Erhard Milch, about their performance and military potential, with Udet being most impressed by the Hawk’s climbing and diving capabilities.

In September 1933, the German Air Ministry wired the funds to purchase two Curtiss Hawk IIs (c/n H-80 and c/n H-81) from the factory in Buffalo, and Udet oversaw their disassembly on the 29th. From there, Udet and the Hawks came to Germany aboard the fast luxury liner SS Europa, arriving in Bremerhaven on October 19, eight days after leaving New York. H-80 and H-81 would be registered on the German civil registry as D-1364 and D-1365 respectively. Later, when the civil registry switched from numbers to letters, D-1364 became D-IRIS and D-1365 assumed the identity D-IRIK.

Soon after they were reassembled, Udet began flying the two aircraft in demonstrations of dive-bombing tactics to the Luftwaffe higher ups at Rechlin airfield, while D-3165/D-IRIK was temporarily fitted with pontoon floats for flight testing and water-handling demonstrations at Travemünde. He also flew the Hawks at airshows in Germany and Switzerland. On July 20, 1934, however, as Udet was practicing aerobatics over Berlin’s Tempelhof Field in D-IRIS, his seat came loose and jammed the controls, with the aircraft entering an uncontrolled spin. Udet was forced to bail out and deploy his parachute, and D-IRIS crashed and burned, leaving only one of the two Curtiss Hawks sent to Germany, D-IRIK.

As Göring sought to elevate his own position and wealth in the Reich, he appointed Udet to oversee the research and development arm of the Luftwaffe, and Udet took his remaining Curtiss Hawk II on further demonstration flights for both Luftwaffe officials and at public airshows in Germany in support of Deutsches Lufthansa (the predecessor to the modern German flag carrier), the German Air Sports Association, and the Luftwaffe, which was formally organized in 1935 in blatant violation of the Treaty of Versailles. On the right side of the vertical stabilizer, it was painted with the old Imperial German flag colors of 1870-1918, while the Nazi flag was painted on the left. During the 1936 Berlin Olympics, Udet flew D-IRIK in aerobatic demonstrations over the Olympiastadion, and the Hawk had the Olympic rings painted on the sides of its fuselage. Udet also competed in the art competitions held in Berlin by offering his 1935 autobiography Mein Fliegerleben (My Flying Life).

In addition to his public flights, Udet took the Curtiss Hawk on perilous dives to simulate those used for dive bombing. With traditional level bombers flying at high altitude and dropping unguided conventional bombs, their accuracy was poor. Though the theory of dive bombing was certainly not a new idea, Udet believed that an aircraft capable of dive bombing could be far more accurate than the heavy bombers then up for consideration. It was further theorized that these aircraft could support ground forces as “flying artillery,” providing the Luftwaffe with a larger number of small tactical bombers to support the advancing infantry and tanks on the ground, creating a category of aircraft called the Sturzkampfflugzeug (diving combat aircraft), more commonly abbreviated in German as a Stuka, leading to the development of the Henschel Hs 123 and the Junkers Ju 87, which would see combat during the Spanish Civil War.

However, Udet’s affinity for dive bombing had its critics within the Luftwaffe, such as Walter Wever, who advocated for long-range heavy bombers, and felt that the strains of dive bombing would be too difficult for average Luftwaffe pilots. However, with Wever’s premature death in a takeoff accident in 1936, dive bomber designs such as the Henschel Hs 123 and Junkers Ju 87 were accepted into service, and other German bombers, such as the Junkers Ju 88 and even the Heinkel He 177 Grief (Griffin) heavy bomber were ordered to be adaptable for dive bombing. Germany’s over-reliance on tactically focused aircraft such as dive bombers would later prove to be a detriment when the Luftwaffe operated in contested airspace beyond the front lines.

In 1939, Göring appointed Udet as the head of the Chief of Procurement and Supply for the Luftwaffe, where he was responsible for overseeing all the production of aircraft and aviation armament for the Luftwaffe, and with supplying these assets to operational units. This desk job, however, was something that even Udet knew he was wholly unsuited for and spiraled further into alcoholism and drug abuse to cope with the stress of his workload, which increased substantially when Germany started World War II in Europe by invading Poland on September 1, 1939. When the Luftwaffe failed to destroy the RAF during the Battle of Britain, and Germany’s straining supply of resources for aircraft production limited its ability to replace lost or damaged aircraft, Göring increasingly blamed these failures on Udet, and Erhard Milch sought to expand his power in the RLM by delegitimizing Udet, which also caused to Udet to increase his alcohol consumption. The last straw was when Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. Udet had inspected Soviet aviation shortly before the invasion and concluded that Soviet aviation was capable of matching German production capabilities for aircraft on equal footing to Germany’s own. His report went unheard by Hitler and his old comrade Göring, who were both fully convinced that the Red Air Force was largely antiquated and would fold under the onslaught of the Luftwaffe. Though the early days of Operation Barbarossa would seem to prove Göring correct, the Soviets were able to move their factories east of the Ural Mountains, far beyond the range of the Luftwaffe’s bombers, and they also began receiving shipments of British and American aircraft through the Lend Lease program, which would outpace Germany’s production.

Meanwhile, the demands of the Eastern Front produced an even-greater strain on Udet, as the German aircraft industry struggled to keep pace with replacing losses and supplying frontline units with, and records being falsified to indicate that production quotas had been fulfilled when in reality they had not. On November 17, 1941, Ernst Udet shot himself with a revolver in his home in Berlin. Göring held an elaborate military funeral for Udet, lying that Udet had been killed while flight testing a new aircraft. Ironically, two more figures were killed in separate plane crashes on the way to Udet’s funeral; the flying ace Werner Mölders and General of the Air Force Helmuth Wilberg.

Udet’s Curtiss Hawk II D-IRIK was placed on display at the German Aviation Collection (Deutsches Luftfahrt Sammlung; DLS) near the Lehrter Bahnhof railway station in Berlin (now the Berlin Central Section). However, with Berlin being within reach of Allied bombers, the threat of destruction from above prompted the evacuation of the museum’s aircraft collection out of Berlin. Unfortunately for aviation historians, many of the aircraft in the DLS did not survive the war, for on the night of November 22-23, 1943, the German Aviation Collection building and the nearby Lehrter Bahnhof were heavily damaged by British bombers. The aircraft that had managed to have been evacuated, though, including Curtiss Hawk II D-IRIK, were shipped by rail to occupied Poland, and were kept in their railway cars in the Polish countryside, far from any targets of aerial bombing. In 1945, Soviet and Polish troops discovered over 20 abandoned aircraft from the DLS, still hidden away in their railway cars near the village of Kuźnica Czarnkowska. The railway cars containing the wings to many of the airplanes, though, including those of the Curtiss Hawk, went missing, lost to the chaos of war. With Germany defeated, the aircraft remained in Poland, now a satellite state of the Soviet Union, being sent from one storage location to the next. In 1963, the Polish Aviation Museum was established in Krakow, where the majority of these historic aircraft, including Udet’s Curtiss Hawk, remain to this day. The Wright Cyclone on Udet’s Hawk was even restored to operational condition and run up on several occasions before a new set of wings was fabricated to be placed on the restored Hawk in the museum.

In 1997, EAA member Hans J. Storck visited the Polish Aviation Museum and was drawn to the Curtiss Hawk II. By this point, there were only a handful of original Curtiss Hawk biplanes to draw data from. The National Museum of the USAF in Dayton, OH, is home to the last surviving P-6E Hawk, USAAC serial number 32-420, while the National Air and Space Museum displays Al Williams’ Curtiss Hawk “Gulfhawk” at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, VA, and the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, FL, displays a rebuilt BFC-2 Goshawk (post 1934 designation for the F11C), BuNo A9332, and the Royal Thai Air Force Museum in Bangkok has a Hawk III (KH-10) on display. None of these, however, were airworthy, and while Storck was intrigued by the idea of building a flying reproduction of the Hawk II, other projects took priority. Fast forward to a night drive to Las Vegas following the final Reno Air Races held in September 2023, and Storck was talking with his driving partner, German aerobatic pilot and fellow EAA member Rainer Berndt, when the idea of the Curtiss Hawk project was brought up. Berndt was interested in the project and agreed to sponsor it, with Storck being the project leader and builder. Storck would also have the task of reverse engineering drawings and plans for the reproduction of the Hawk II, but with little in the way of such things, Storck and Berndt headed to Krakow in November 2023 to revisit Ernst Udet’s Hawk D-IRIK.

Being overwhelmed by the historical nature of the aircraft, Storck and Berndt also received a tipoff from the curator of the Polish Aviation Museum. When the museum was refabricating the wings for the Hawk, they had been assisted by another EAA member, Fred Barber, who had technical drawings for the wings and other parts of the aircraft. After Storck got in contact with Barber, Barber revealed that he had all kinds of information on both the Army and Navy Curtiss Hawks. He had found microfilm rolls with original Curtiss drawings of the Curtiss Hawks in the archives of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. The quality of these films, though, was too poor to be used directly for reference, so Barber made new drawings by printing out around 280 small sections of key drawings and taped them together. These drawings revealed that the fuselage structure of the Navy F11C and the Army P-6E were identical with the exception of the engine mounts, as the F11C had a radial engine while the P-6E had an inline one. These mounts could now be replicated using the originals as reference materials. Fred had sold his drawings for the wings of the Curtiss Hawk to Fagen Fighters of Granite Falls, MN, after he decided no one was going to build one. Fortunately for Storck, however, Fagen Fighters was generous enough to send him full copies of Barber’s wing drawings, along with a box of cast airframe parts provided to them by Barber. Storck has now incorporated all of the Curtiss drawings, the F11C handbook, and measurements of Udet’s Hawk in Krakow in his workshop materials.

During the 2024 EAA AirVenture in Oshkosh, WI, Storck, Berndt, Barber met with John Saunders and Matt Bauer at the EAA Aviation Museum, which has a full-scale replica of a Curtiss P-6E Hawk on display. This replica had been constructed by Ralph Rosanik of Omaha, NE, who as a boy had seen the originals in service during the 1930s at Chanute Field in Rantoul, IL and spent years looking for an original Curtiss Hawk before deciding to build one after only finding a single wing. He spent 25 years building a P-6E Hawk, which he debuted in June 1992, at the EAA Chapter 80 Fly-In in Council Bluffs, IA before flying it to EAA Airventure in Oshkosh, where he later donated the aircraft in 2000. Rosanik also documented his journey of rebuilding and researching the Curtiss Hawk in the book Hawk Safari: The Search for a Rare Bird, which has served Hans Storck as a must-have resource for his own project.

However, as Storck himself notes, the team hopes to have their Curtiss Hawk done in four years saying, “we’re not getting any younger and need to make the best of our time and now with Fred’s help we are really getting up to speed.” The team of between eight to ten enthusiasts has now completed the CAD design of the wings, bonded the wing spars, machined the plywood for the wing ribs, and ordered all the steel and aluminum material, with the landing gear build currently in progress. One key feature of the aircraft that is still needed, though, is an engine. The restoration team is hoping to find an original Wright R-1820-F Cyclone nine-cylinder radial engine with direct drive and a 40-spline prop shaft, along with the matching propeller, as seen on the original now in Krakow. The team is looking for more leads to help them find such an engine and would also like to establish ties with the antique aviation community in Germany for further assistance.

Special thanks to Hans Storck for his assistance in the writing of this article.