In 1942, the first American jet aircraft, the Bell P-59 Airacomet, made its first flight. However, flight testing showed the aircraft to be underpowered, with its overall characteristics being inferior to conventional piston engine designs. As such, as the USAAF sought a new more powerful jet aircraft. Ironically, they had already turned down such a proposal from Lockheed Aircraft of Burbank, California, who had proposed the L-133 jet fighter, that was to be powered by two axial-flow jet engines. By 1943, with reports of German advances in jet aviation, the USAAF issued a contract for Lockheed to build an airplane around the Halford H-1 jet engine (which was manufactured by de Havilland and later remarketed as the de Havilland Ghost).

Designer Clarence “Kelly” Johnson, Lockheed’s Chief Research Engineer, brought up the Model L-140 proposal, which was a simple design that took inspiration from the L-133, with the nose being similar to Lockheed’s P-38 Lightning. The USAAF was so impressed with the proposed design and Kelly’s promise to have the aircraft ready for flight testing in record time that a contract for the XP-80 was issued, stipulating that Johnson and his team had 180 days to build an airworthy prototype, starting on June 21, 1943, with the contract being accepted by Lockheed’s Vice President and Chief Engineer Hall Hibbard.

Now that the XP-80’s contract was in place, a select team of 134 employees from Hibbard and Johnson to 105 mechanics and 23 draftsmen and engineers, worked around the clock away from prying eyes at the Lockheed Advanced Development Projects division. The stench from a nearby plastics factory led to engineer Irv Culver naming the plant “Skonk Works” in reference to the popular comic strip Li’l Abner. This name was later changed to “Skunk Works”, which remains associated with Lockheed-Martin to this day.

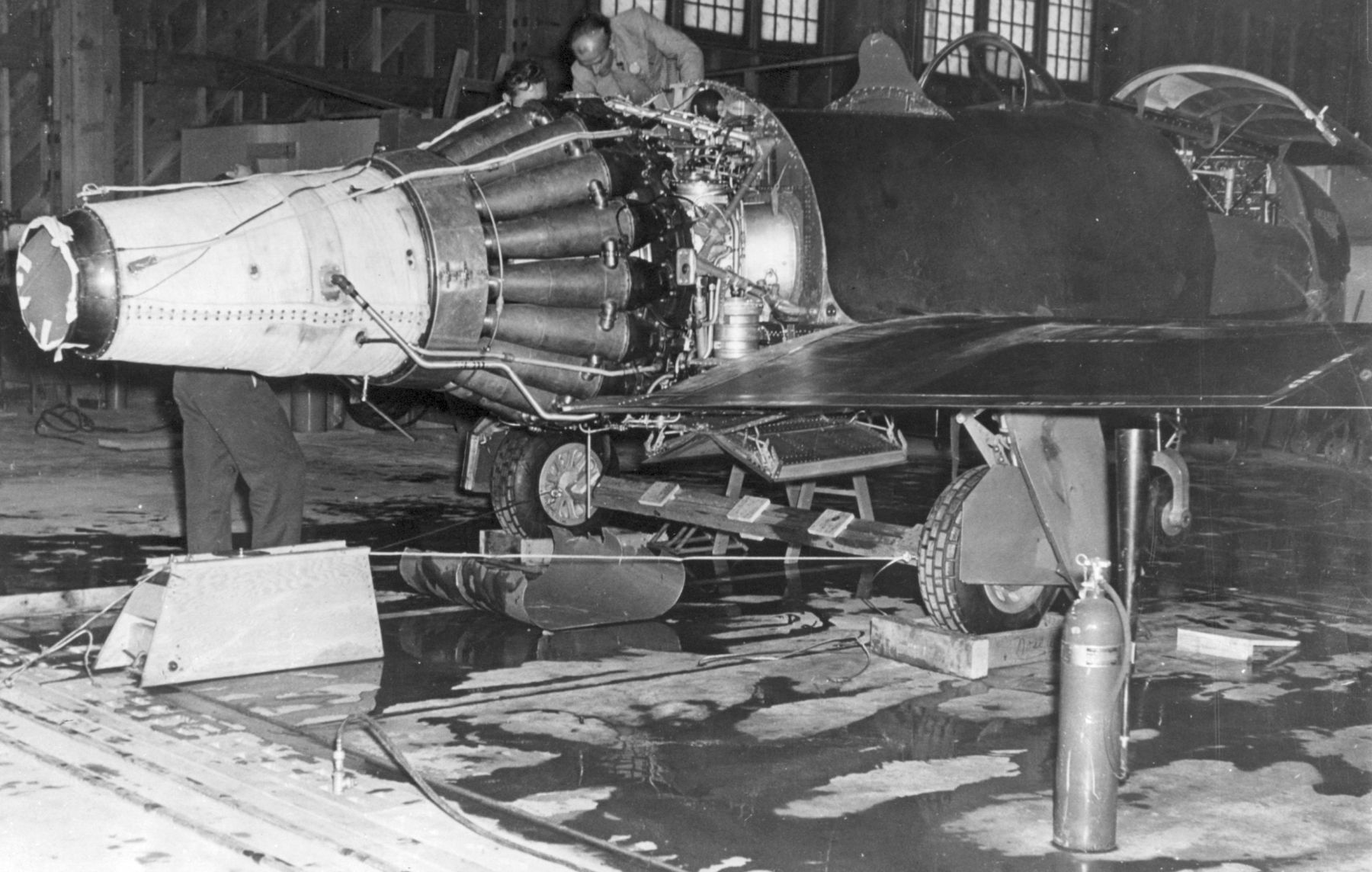

Meanwhile, work progressed at break-neck speed. On July 20, 1943, USAAF officials inspected a full-scale wooden mockup of the XP-80 at the Lockheed factory in Burbank while the unfinished prototype was still under wraps. By the night of November 2, the H-1 engine had arrived from England, and by November 9, the XP-80, construction number 140-1001, was assembled, painted in a Dark Green and Light Gull Gray scheme, polished, and weighed. Five days later, on November 13, 1943, the XP-80 was disassembled and trucked from Burbank to Muroc Army Airfield (now Edwards Air Force Base), and the USAAF officially accepted the Lockheed XP-80 into service as USAAF #44-83020, having gone from design to service testing in 143 days.

That same day, ‘020 was having its Halford engine ground tested before the subsequent flight tests. Then, during one such test on November 18, the inlet ducts collapsed, damaging the engine. Despite having the aircraft delivered to the USAAF, the team needed to get another Halford H-1. An engine had to be removed from the prototype de Havilland DH.100 Vampire to be shipped from England, which did not arrive at Muroc until December 28, by which point new inlet ducts had been delivered and installed on the aircraft. At last, on January 6, 1944, the XP-80 was deemed fit to fly, but with winter rains making the lakebed wet, it was decided to delay the first flight until the ground hardened once more.

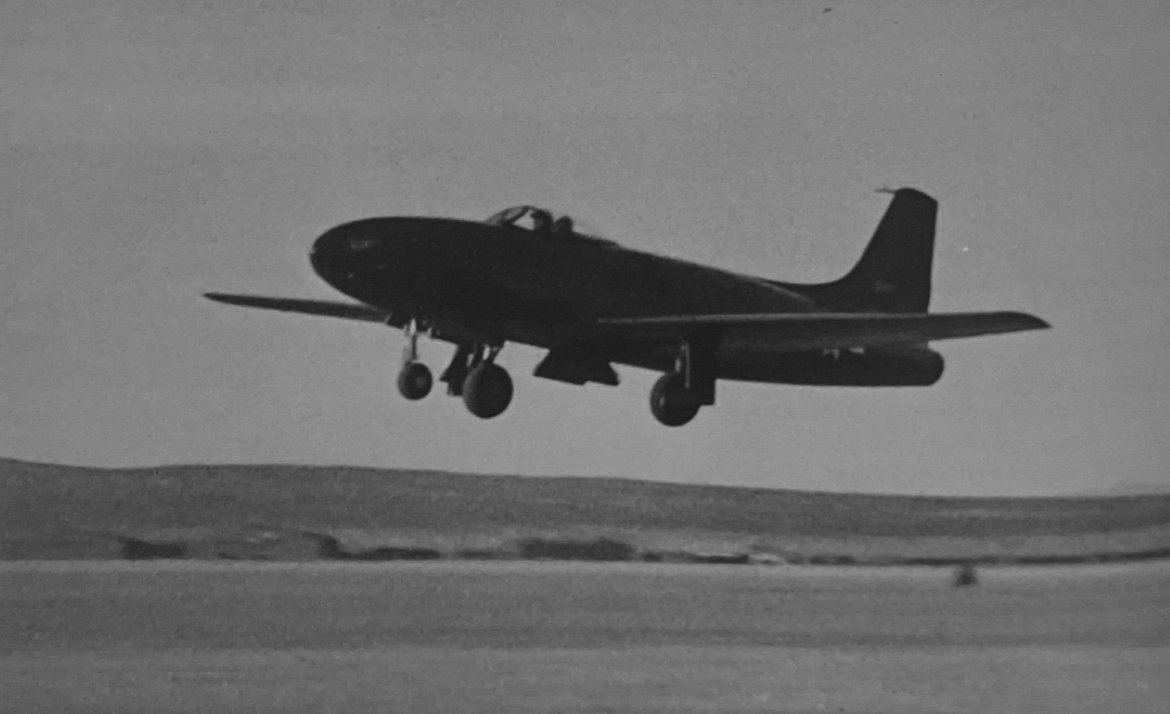

On January 8, 1944, Lockheed test pilot Milo Burcham took Lulu Belle, aloft on its maiden flight before an entourage of military and civilian VIPs at 9:10am local time. Just five minutes later, however, Burcham landed the aircraft, having been unable to retract the landing gear and was unaccustomed to the high sensitivity of the hydraulically assisted ailerons. However, the gear did not retract because of a safety switch left in place, and Kelly Johnson reassured Burcham of the sensitivity concerns. With that, Burcham took off again, and showed what the aircraft could do. A veteran aerobatic pilot of prewar airshows, Burcham reached an Indicated Air Speed (IAS) of 490 mph, and put on a stunning low-level performance just above the desert in front of the small crowd, then pulled up into a steep climb as the Goblin engine roared overhead. It was clear to all in attendance that day on the dry lakebed that they had a high-performance aircraft on their hands.

Further prototypes would follow soon after Lulu Belle, including two XP-80As and 12 YP-80As, with four YP-80As even being sent to Europe for operational flight testing, with two being shipped to England and two going to Italy. Although the P-80 Shooting Star was ordered into production with the intent of equipping combat units, production delays and the loss of several prototypes in flying accidents that claimed the lives of several test pilots, including Milo Burcham on October 20, 1944, and America’s Ace-of-Aces Richard Ira “Dick” Bong in a production model P-80A on August 6, 1945, ensured that the Shooting Star was ready to see combat during World War II. However, the P-80 still became the first American jet fighter to enter operational service, and with the creation of the US Air Force (USAF) as its own separate branch, the P-80 became the F-80.

As the F-80, the Shooting Star would see combat with the USAF during the Korean War, in which it was the initial frontline fighter for the USAF until the arrival of the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 prompted the deployment of its successor, the North American F-86 Sabre. The Shooting Star remained in Korea, however, escorting Boeing B-29 Superfortresses on raids against North Korea and being flown as a fighter-bomber.

Additionally, the F-80 served as the basis for the USAF’s first jet trainer, the T-33, which was widely used by the USAF and numerous countries around the world. The F-80 was also adapted for service in the US Navy and Marine Corps as the TV-1, and the F-80 fighter was also exported to Latin American countries such as Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Uruguay, where many of these served well into the 1970s.

After its initial flight testing, Lulu Belle (which was also nicknamed the Green Hornet for its paint scheme), was modified with a new, rounded tail and new wingtips and remained in use as a test aircraft. From July 26-29, 1944, Lulu Belle and the XP-80A USAAF #44-83021 Gray Ghost (just one month after Gray Ghost‘s first flight) were used to simulate attacks on B-24 Liberators escorted by a range of fighters to devise tactics for escort fighters to combat jet aircraft. Among the aircraft used as escorts in the test flights were P-38 Lightnings, P-39 Airacobras, P-47 Thunderbolts, P-51B Mustangs, and P-59 Airacomets, which showed that bombers needed their own escort of high-speed jet aircraft, but suggested that the best way for conventional piston engine fighters to protect the bombers under their charge was to employ large, flexible formations close to the bombers and press head on passes against attacking jets.

In November 1944, Lulu Belle was assigned to the 412th Fighter Group, the USAAF’s first jet fighter group, flying alongside Bell P-59 Airacomets at Muroc. The aircraft was later reassigned in 1945 to the Army Air Force Training Command at Chanute Field, Illinois for ground schooling until it was returned to Muroc for further flight testing of its Halford engine. On November 8, 1946, Lulu Belle was placed in storage at Park Ridge, Illinois for preservation alongside other historic aircraft selected for preservation by General Henry “Hap” Arnold. On May 1, 1949, 44-83020 was among the aircraft at Park Ridge selected for the Smithsonian’s new National Air Museum.

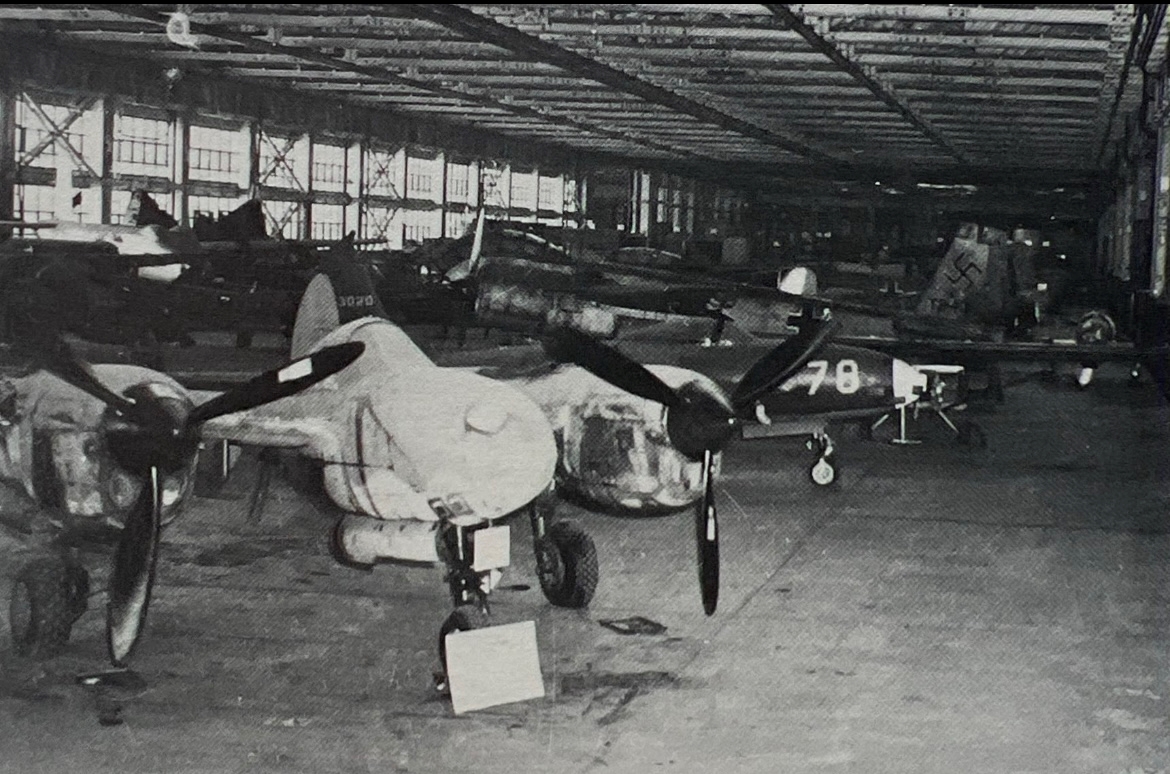

By the early 1950s, Lulu Belle was among numerous aircraft shipped from Park Ridge to the Smithsonian’s Silver Hill facility in Suitland, Maryland, remaining in storage, disassembled in packing crates until October 1976, when it was selected for restoration by the National Air and Space Museum. After around 4,841 man-hours, Lulu Belle was completely restored by May 1978 and later placed on display in the museum’s Jet Aviation gallery in Washington, D.C., alongside the Smithsonian’s Messerschmitt Me 262 and McDonnell FH-1 Phantom.

In 2019, the Lulu Belle was moved out to accommodate extensive renovations to the D.C. branch of the National Air and Space Museum and has been placed back in storage. As the renovations are still ongoing, it is not certain when Lulu Belle will go back on public display. However, the legacy of the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star remains today in the aircraft that came after Lulu Belle that pushed America into the Jet Age, and secured Lockheed Aircraft’s place as an innovator among American jet technology.

Today in Aviation History is a series highlighting the achievements, innovations, and milestones that have shaped the skies. All the previous anniversaries are available HERE

The development of the Shooting Star started in late ’43, and when the Service Test Prototypes went into service, the war in Europe had ended, and the entire War had ended before the first production examples could be sent into combat. Only two YP-80’s were destroyed, and Bong was killed in the crash of a production P-80A, not a YP-80.

Hi John, I have back and made some edits to the article. I apologize for not making things clear enough.