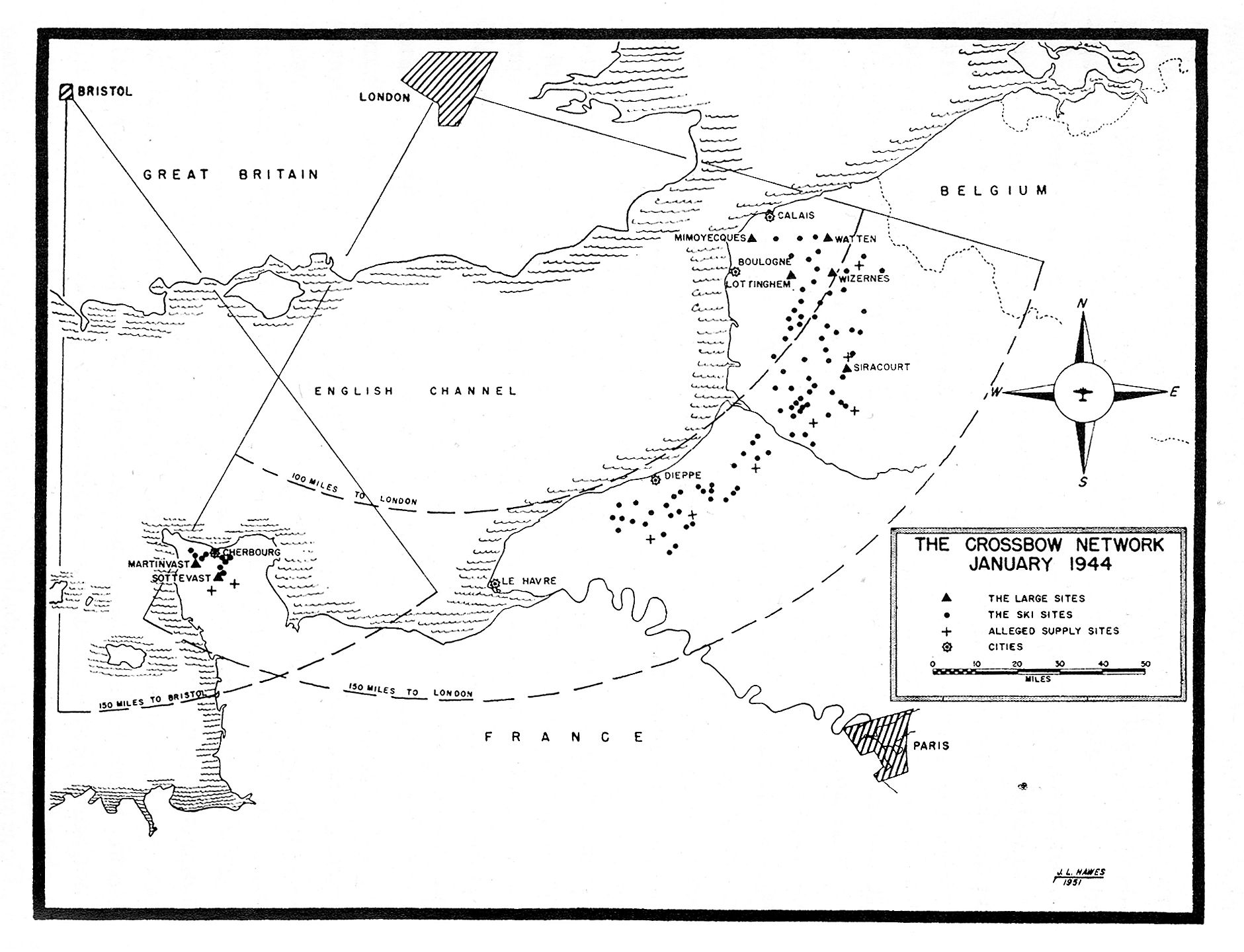

With much of continental Europe under German occupation, resistance organizations were a key component in disrupting the infrastructure used by the Germans to extract resources and in sending intelligence reports back to the Allies. As 1943 came to a close and 1944 began, the French Resistance in northern France was not only a critical asset in reporting on the state of German defensive points along the coast of the English Channel, but on launch sites for V-1 flying bombs as well.

Yet the Germans were just as committed to finding and arresting resistance members for interrogation, forced labor, and execution. One area in which the secret police, the Gestapo, and the German military intelligence branch, the Abwehr, (with help from collaborators) had arrested much of the resistance was around Amiens and Abbeville, and then imprisoned them in the Amiens Prison, a crucifix-shaped complex built in 1904. The prisoners included members and leaders of the Organisation civile et militaire (Civil and military organization: French acronym OCM), including the last free OCM to be arrested, Abbeville sous-préfet (subperfect) Raymond Vivant, who was captured on February 14, 1944.

When news of Vivant’s capture reached London, the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) and the American Office for Strategic Services (OSS; precursor to the CIA) feared that if the Germans learned how valuable the intelligence Vivant and his comrades had was, it would destroy all local resistance activities in that sector of northern France. A plan was then hatched, using intelligence gathered by the Resistance from agents inside the prison and smuggled out by those outside its walls, that the Allies would stage a prison break. But they had to act fast: as several of the prisoners were scheduled to executed on February 19.

Enter 140 Wing of the RAF 2nd Tactical Air Force. Highly trained in low-level precision flights, they were to fly their De Havilland DH.98 Mosquitos across the Channel and drop bombs at strategically placed points to level the gates and open a breech in the prison walls for the prisoners to escape. Meanwhile, they would be escorted by Hawker Typhoon fighters that were to distract the Luftwaffe’s Focke Wulf Fw 190s that would be scrambled to intercept them. Classified as a “Ramrod” mission (a short-range bomber attack to destroy ground targets), the operation was known during the war as Ramrod 564, but it was not until after the war that the operation was called Operation Jericho.

The mission would involve no less than 18 Mosquito strike aircraft from No. 140 Wing, with six from No. 487 Squadron, Royal New Zealand Air Force, led by Wing Commander Irving “Black” Smith, six aircraft of No. 464 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force, led by Wing Commander Bob Iredale, and a further six of Six Mosquitos of No. 21 Squadron RAF, led by Wing Commander Ivor “Daddy” Dale. No. 487 and No. 464 were assigned to destroy the quarters for the German guards and create openings in the walls for the prisoners to escape. The Mosquitos of No. 21 Squadron had a grimmer task than their counterparts: should the New Zealanders and Australians fail in their mission; they were to bomb the prison and kill the prisoners inside so that the Germans could not interrogate them. The men of No. 21 Squadron RAF had faith in their Commonwealth comrades, and when the men of No. 487 Squadron RNZAF and No. 464 Squadron RAAF learned of No. 21 Squadron’s assignment, they were determined not to fail, studying a scale model of the prison to determine the best point to drop their bombs on their assigned targets. Additionally, a photo-reconnaissance Mosquito would fly alongside them to capture the outcome of Operation Jericho for the Royal Air Force’s Film Production Unit (RAFFPU) to distribute to the newsreels shown in movie theaters back home.

Although the French Resistance did not directly order the raid against Amiens prison, British intelligence sent requests to the Resistance for intelligence on the prison, from which they sent MI6 critical information on the daily schedule, including when the guards and the prisoners went on lunch, and even had operatives get arrested so they could inform the prisoners of the upcoming raid.

In the early morning hours of February 18, 1944, the three squadrons attended a briefing at 8:00am to learn everything they needed to know before setting off from RAF Hunsdon to attack Amiens Prison. Group Captain Percy “Pick” Pickard, commander of No. 140 Wing who had gained fame for his involvement in the wartime propaganda film Target for Tonight (released in 1941), briefed the men on the mission, then climbed into Mosquito fuselage code EG-F (RAF s/n HX922), joining navigator Flight Lieutenant John Broadley.

Originally Air Vice-Marshal Basil Embry, commander of No. 2 Group RAF had requested to lead the mission himself but was grounded for his involvement in the planning of the upcoming invasion of Normandy. Pickard was chosen to take Embry’s place, but Pickard himself changed the schedule to be the 12th aircraft so he could be in a position to observe the result of the first wave’s attack. Reportedly, when the Australian and New Zealander pilots could not determine who would strike the walls and who would hit the guard towers and barracks, the commanding officers of 487 Squadron and 464 Squadron flipped a coin, and the result led to the New Zealanders going in first, led by Wing Commander Smith, flying Mosquito EG-R (serial number LR333) with Flight Lieutenant P.E. Barns DFC as navigator.

Despite the airfield being covered with snow and in the midst of blizzard conditions, the mission was a go-ahead, and after the 18 Mosquitos departed Hunsdon at 11:00am, they rendezvoused with Hawker Typhoons of No 174 RAF, while weather conditions at RAF Manston prevented the Typhoons of No. 198 Squadron RAF to be delayed in their takeoffs.

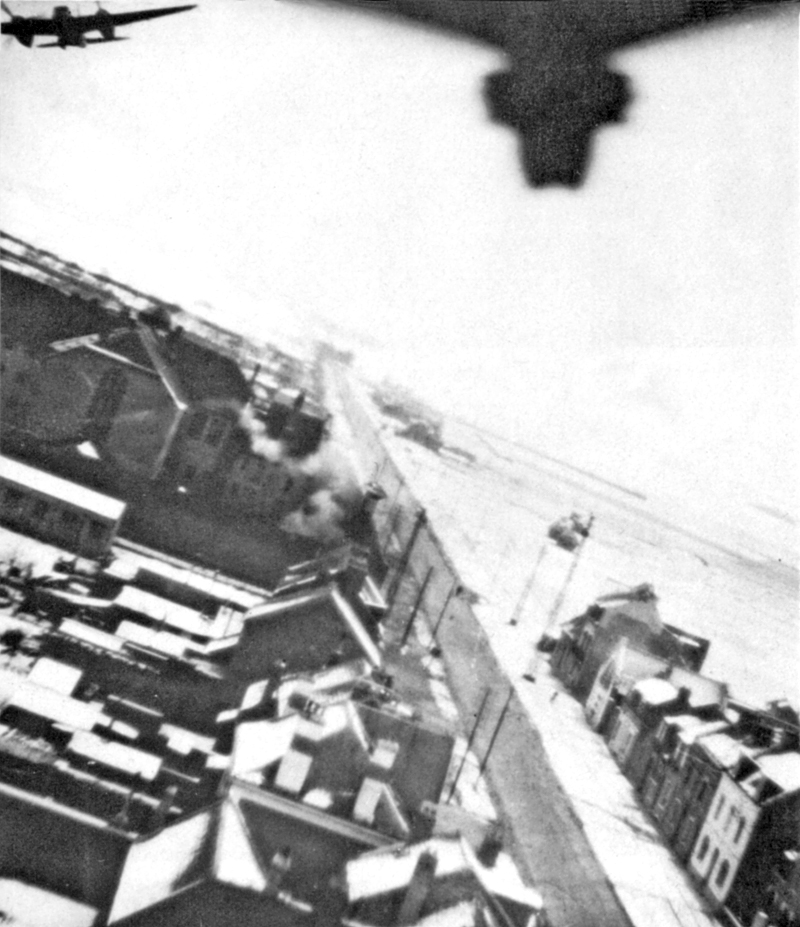

Flying at wavetop level across the English Channel, the Mosquitos and their Typhoon escorts made landfall near the Norman commune of Le Tréport, then turned east in order to distract the German fighters at Abbeville and Glisy before turning southeast above Doullens for the Somme town of Albert. Albert was also important in navigating to Amiens, as the main road travelling southwest from Albert led directly to Amiens, and the prison was situated on that same road. The Mosquitos flew so low that they had to tip their wings to avoid hitting the tops of the poplar trees that lined the road with their wings. Then, as one of the 487’s pilots described it, “The poplars suddenly petered out, and there, a mile ahead, was the goal. It looked just like the model, and within a few seconds we were almost on top of it.”

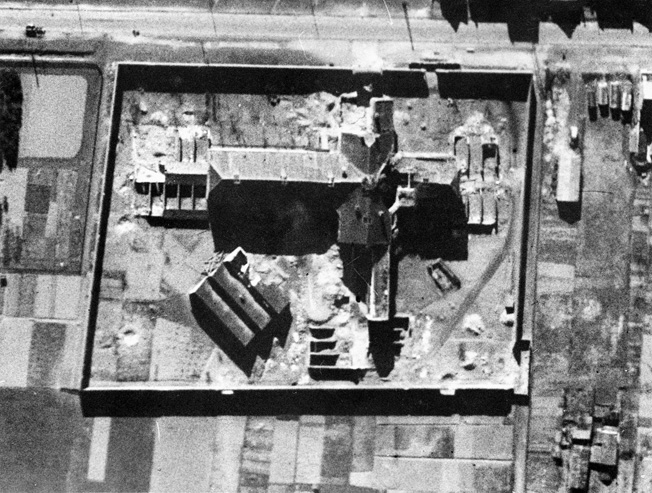

At 12:01pm, the silent winter air was filled with the roar of Rolls Royce Merlin engines, machine gun and cannon fire, and exploding bombs set to 11 second fuses to allow the Mosquitos enough time to escape the blast radius. Three of the six aircraft of 487 Squadron RNZAF were the first to hit Amiens prison, targeting the northern and eastern walls. Five minutes later, at 12:06, two Mosquitos of 464 Squadron RAAF dropped their bombs on the eastern wall as another two struck the main building from 100 feet, breaching the prison and allowing the French prisoners to make their escape. The Mosquitos coming in from the north of the prison flew so low that they kicked up snow from the fields outside the prison. Upon observing the damage to the prison and the escape of the prisoners, Pickard called off the Mosquitos of No 21 Squadron and ordered them to return to base.

Soon after recalling No 21 Squadron, Pickard and his navigator John Broadley were attacked by a Focke Wulf Fw 190 flown by German ace Feldwebel Wilhelm Mayer, whose cannon fire severed the tail of Mosquito HX922, which fell near the village of Saint-Gratien, killing Pickard and Broadley instantly. One other Mosquito was forced down near Albert by German anti-aircraft fire during Ramrod 564, fuselage code SB-T (serial number MM404), flown by pilot Squadron Leader A. I. McRitchie, RNZAF and navigator Flight Lieutenant R. Sampson, RNZAF. While F/Lt Sampson was killed, S/Ldr McRictchie, who was wounded during the crash landing, was taken as a prisoner by the Germans. Of the escorting Hawker Typhoons, Flying Officer J. E. Renaud of No 174 Squadron was shot down 4 miles north of Amiens by Leutnant Waldemar Radener, with Renaud being captured after force landing his Typhoon, s/n JR133. Meanwhile, F/Sgt H. S. Brown of No 174 Squadron was reported as missing after entering a snowstorm 20 nautical miles off Beachey Head, and to this day, his remains have never been confirmed to have been discovered.

Of the 832 prisoners held in Amiens prison on February 18, 1944, 102 were killed in the raid, either by the bombs dropped by the Mosquitos or by the surviving guards as they tried to escape. Between 255 and 258 men managed to escape, but 182 were soon recaptured. Nevertheless, the resources used to track down the escapees were diverted from other counter-insurgency operations, and the prisoners that had managed to escape were able to identify the informants who had turned them in. The raid also inspired further acts of resistance in northern France in the leadup to the Normandy Landings and the Liberation of France.

Today the prison at Amiens still stands with a plaque dedicated to the prisoners killed in Ramrod 564 (Operation Jericho), while a memorial at Hunsdon Airfield to all the personnel who served there from 1941 to 1945 also includes the airmen who flew on this mission. The event would also go on to inspire works of popular media such as the 1969 movie Mosquito Squadron, which was a fictional account that used elements of the real event in its story, and the story has been the subject of numerous books and documentary programs over the years.

Today in Aviation History is a series highlighting the achievements, innovations, and milestones that have shaped the skies. All the previous anniversaries are available HERE