If you’ll forgive us this telling of a story that’s on a slight tangent from our normal warbird fare: The mariners of the Merchant Marine, though they were not accorded the honors bestowed upon the other units and services of World War Two, nonetheless suffered among the highest casualty rates of those serving their countries’ war efforts. Frank McLaughlin served in the UK’s Royal Merchant Marines and twice had his ship torpedoed out from under him, once by a Japanese submarine in the Mozambique Channel in 1942 and again in the Mediterranean when his ship was sunk by a torpedo launched from a Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 piloted by Italian aviator, Dalmazio Corradini.

If you’ll forgive us this telling of a story that’s on a slight tangent from our normal warbird fare: The mariners of the Merchant Marine, though they were not accorded the honors bestowed upon the other units and services of World War Two, nonetheless suffered among the highest casualty rates of those serving their countries’ war efforts. Frank McLaughlin served in the UK’s Royal Merchant Marines and twice had his ship torpedoed out from under him, once by a Japanese submarine in the Mozambique Channel in 1942 and again in the Mediterranean when his ship was sunk by a torpedo launched from a Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 piloted by Italian aviator, Dalmazio Corradini.

Frank McLaughlin (August 21, 1921 – ) was born and raised in the city of Londonderry or “Derry” in Northern Ireland during a time of extreme sectarian violence, the city just recently separated from Ireland proper as a result of the Anglo-Irish Treaty which made Northern Ireland the primary warfront for the nationalist IRA movement which sought to unite the entire island of Ireland into a single unified republic. Frank’s father was an auto mechanic and a native of Derry and his mother was a farmers daughter from County Mayo who was working as a nanny when they first met.

Growing up, times were tough in Derry as along with the ongoing sectarian violence, the city suddenly found itself divorced from the county that had historically been the source of most of its trade, being recast as a border town between two recently warring nations. Frank recalls that while it wasn’t a time of plenty, there was always food on the table and a strong sense of community. Frank attended Catholic schools and had a uncomplicated childhood typical of the times, with idyllic summers spent with his mother’s family at their farms in County Mayo on Ireland’s West coast. Both Derry and County Mayo had quite active seaports and it was thus that the young McLaughlin became enamored with the sea. A voracious reader, Frank read everything he could about seafaring, his heroes as a young man were the great historical figures Scott, Amundsen and Nelson. He also enjoyed the adventure tales of novelist Robert Louis Stevenson.

Frank had uncles who were seafarers and would focus rapt attention to their tales of life upon the waves. Living near the docks, he would spend hours watching the ships come in and out of port and watch the crews scurrying upon the decks, loading and unloading cargo going to and from the far corners of the world, dreaming of the day when he could join the crew of one of those ships and see the world.

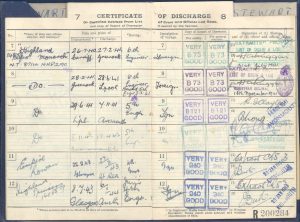

The British Merchant Navy of the day boasted nearly 6000 ships and traded all across the globe. There were several routes one could take to join the crew of these ships, poor or orphaned children were able to be trained for free to be deck hands, stewards or cabin boys, while schools existed for boys from less-modest means to accomplish their pre-sea training, after which they could apply for an apprenticeship and eventually become deck officers after three or four years. There were also schools to train radiomen, which required three years to complete, though at the outbreak of the war, given the shortages of manpower it created and the requirement that all ships have at least three radiomen, the course requirement for a radioman’s position was reduced to just nine months. Seeing the path of least resistance to get out on the open ocean, Frank enrolled in a radioman training school in Belfast and after nine months graduated. While he might have preferred to train as a deck officer it was not to be. War or no war he would have gone to sea; as he put it, he really had no other ambitions.

At 18 Frank joined his first ship, the Nicoya, out of Liverpool. While leaving port she was bombed and sustained some damage but fortunately onboard there were no casualties. Frank recalls sailing down the Mersey River heading for the open ocean and witnessing the docks and warehouses on both sides of the river burning fiercely. Much of the ships crew were from Liverpool from whence the ship was departing and the men lined the rails of the ship in silence, watching their city being bombed by wave after wave of Luftwaffe aircraft.

Frank’s wartime experiences were hardly unusual, his family back home were working in the shipyards, munition factories and aircraft industries and letters to and from home were heavily censored, leave was infrequent and short and often families had no idea of one’s whereabouts. As crews aboard ships were constantly changing, building lasting friendships during those days were well nigh impossible.

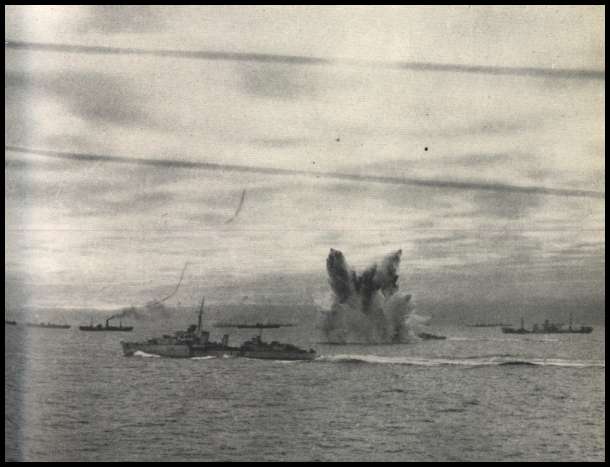

(Image Credit: Library of Contemporary History, Stuttgart)

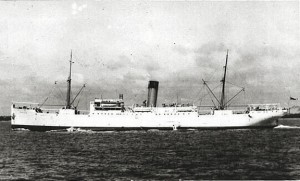

Frank was an employee of the Marconi International Marine Communications Co. who provided radio operators as well as the radio sets themselves to the shipping companies. Assigned as a Junior Radio Officer to the SS Hartismere, a 5500 ton merchant steamer with a crew of 47 aboard, Frank was in the radio room with the other two radio operators as the ship sailed unescorted through the Mozambique channel around midnight of July 8th 1942. The ship was partway through a voyage from Philadelphia to Alexandria, Egypt by way of Lourenço Marques from which it had departed on the 4th of July. Frank had just stepped outside when a torpedo struck the ship on the starboard side, right below the bridge. There was a huge explosion and Frank describes the ship rearing up in the air like a whale. He rushed back into the radio room where the Chief RO was sending out a distress call. The 3rd RO meanwhile was struggling to get to the bridge wing in order to heave the ships code books overboard lest they fall into enemy hands.

The Hartismere was burning as the order was given to abandon ship. The lifeboats were lowered into the water, all hands managed to escape with their lives. Though they were in tropical waters, the night was still cold, and while she was burning, the Hartismere seemed to refuse to sink. Taking the initiative, Frank re-boarded the stricken ship and retrieved exposure suits which he threw down to his shipmates in the lifeboats below. He also took the opportunity to get the first mate’s sextant and a picture of his then-girlfriend from his quarters. The submarine commander at that point must have lost patience with this still stubbornly-afloat steamer as he surfaced and began shelling the ship to hasten it’s sinking. Working his way back to the lifeboats, Frank spotted the ships cat but was unable to get a hold of it to bring to the lifeboat so sadly while the entire crew did manage to escape there was that one casualty.

As they pulled away from the now-sinking and blazing stem to stern ship, Frank reflected on how to his mind it had been a happy assignment and something of a home to him, now lost. The captain’s lifeboat was soon tied to theirs and the crew set about making their way to the eastern coast of Africa which was a neutral Portuguese colony at the time. Many of his crew mates were in shock and all were frightened as they set out that night on the dark open sea, leaving the diminishing glow of their sinking and burning ship behind, towards the promise of land and safety some 200 miles away.

When the sun came up, the crew raised sails to assist in propulsion and they made their way slowly west. The shock of recent events sent some of the men into a state of torpor, unable to assist in the routine of sailing their life boats towards safety, instead just staring blankly off towards the horizon. While on the lifeboats the crew subsisted on emergency rations of Pemmican, a nutritive-dense preparation of fat and meat similar to jerky, Horlicks malt tablets and some precious water. Frank is unsure how many days they were out at sea, he recalls the days as hot and the nights as cold but otherwise it was all a blur. Eventually, they made landfall at Caldera Point and were spotted by a Portuguese plane that dropped a message in a canister with a note saying he would inform the British Consulate in Lourenço Marques of their whereabouts. Some natives found them and brought the men to a pineapple plantation run by Germans and fed and sheltered them overnight.

As the owners of the plantation were unlikely to take kindly to sheltering an Allied crew on their premises, the next morning the natives assigned one of their own to guide Frank and his crew to a Portuguese village. There the men were welcomed warmly, fed and divided up among the various homes of the villagers that would host them until the British Consulate could arrange their transport. They ended up staying in the village for about a week, and Frank was deeply moved by the kindness and hospitality shown to him and his mates by these strangers. A truck arrived to transport them to Beira, where they caught a Portuguese passenger ship to Lourenço Marques. After a short stay they traveled by train to Durban where they embarked on the RMS Monarch of Bermuda, bound for Scotland by way of Cape Town.

After an all too short survivors’ leave Frank joined the Empire Rowan as the 2nd Radio Officer on September 3, 1942, as such he was fairly new to the ship when it met its fate on March 27, 1943. On that morning, Frank was on radio watch as the ship was steaming through the Gulf of Philippeville, off the coast of Algeria when their convoy came under attack from Italian torpedo bombers. Frank soon found himself strapped in to one of the ships Oerlikon guns with a DEMS gunner serving up fresh ammunition drums to keep the gun firing.

Frank remembers seeing the torpedo tracking towards the ship and the explosion that followed. The ship keeled over quite quickly and the DEMS gunner jumped overboard. Frank never saw him again. After struggling to get himself unstrapped from the gun, Frank jumped from the gunner platform to the deck, where he landed badly, injuring both of his legs. At this point an engineer happened upon him and though badly injured himself, helped Frank into a port side lifeboat. The boat contained 11 men from the Empire Rowan, and some were badly burned. Frank and his shipmates were picked up in fairly short order by the HMS Stornaway, and Frank had to pull himself up the cargo netting draped over the side of the ship using his arms alone as his legs were too badly injured to offer much assistance.

Frank was placed on his own in a cabin, suffering from shock due to his injuries and the trauma of his recent experiences. The next this he remembers is being lifted out of a lifeboat and carried through shallow water to a makeshift triage unit on the beach where he was laid out amongst other injured men. He remembers an individual moving down the line of casualties and asking their religion. Frank answered “Catholic” and the badly burned man next to him answered “Cattolico” which also served to identify him as an Italian, likely a crew member from one of the eleven planes Frank’s convoy managed to shoot down during the attack. The irony of two men who shared the same faith trying to kill each other was not lost on Frank, even in his state of shock.

Frank was soon moved to a field hospital in Bone (now Annaba). He remembers there was heavy fighting close by, as he could hear the artillery and there was a constant stream of casualties moving through the hospital, all of whom appeared to be British. After recovering from his injuries he travelled by train to Algiers and was repatriated to the U.K. on the SS Franconia.

Frank’s final wartime ship was the MV Empire Chapman, a fuel tanker assigned to transport aviation fuel between the oil refineries of New Jersey and by then Allied-occupied Italy.

While we have detailed only the most dramatic events of Frank McLaughlin’s wartime experiences, he was aboard other ships that were attacked but not sunk, and experienced the terror of being in a North Atlantic convoy in the middle of the night and hearing and sometimes watching his fellow merchant marine ships exploding in the inky darkness.

Frank continued to work for Marconi after the war. Over the course of his career on the seas which ran from 1940 to 1982 Frank estimates that he sailed on 40 British, four Arab, two Greek and one Danish ship.

He met Louise Mary Hughes, the woman who was to be his wife while on leave in Dublin at a church social dance and describes it as love at first sight. He proposed two days later and they were married within the year, remaining together for 51 years until she passed away. Frank and Louise had four children and at latest count, 11 grandchildren.

Frank was awarded the campaign ribbons and awards granted to the those serving in the British Commonwealth forces, but as he was in the Merchant Marine he was not entitled to receive the normal decorations for combat actions as other did. Certainly when one looks at the casualties, risks and heroism of those who served in the Merchant Marine it’s hard to justify them not receiving the recognition that any reasonable person would say they are rightfully due.

Article re-written and published with the permission of Ken Arnold.

Hi,

Frank McLaughlin was my Granddad. He was an absolutely amazing man! Miss him a lot and all of his stories he told us 🙂 ! I loved reading this!

Hannah

Hannah,

He was surely a great man. We are glad you were able to find us and read this article!

Moreno.

He was a true hero rest in peace Grandad

Interesting to see this re-write of Ken Arnolds 2007 article. His more complete story can be found on his excellent site, ( Ken Arnold1919 home page). Thanks to Warbirds for publishing this piece.

Bryan, Ken’s website is a hidden treasure.

I spoke to him years ago and got his permission to use some of his work. I tried to email him few times in the past year but the email bounces back.

Hi there,

can’t seem to contact Ken, his amazing web page seems to have disappeared. I seem to remember there used to be a link through an italian ww11 page which talked about the sinking of the Empire Rowan. One of the pilots tells his story. Thinking of putting together a memoir of my Dad’s war service. Any advice gratefully received.

Frank was my amazing Dad , not only was he our hero, he was such a talented , clever and loving man . The stories he told us were amazing ,we miss all that now. Rest In Peace my pops x x x

Well he was my amazing dad. Such a talented, clever and caring man he was . My Pops. X x x x

I’m filled with immense pride reading this, what a true hero and I find it an absolute privilege to have known him and even more of a privilege to call him my Grandad. He is sorely missed

I an a relative of Francis from the U.S. When Francis was in the states in 1944 he looked up my mom and her siblings. They had a wonderful visit. The next time anyone from our family would see Francis would be over 50 years. When my cousin frank went over to Ireland and looked him up. Thank God he did because all of our cousins in th US. Got to meet this wonderful man and also meet most of his family . We keep in contact and visit each other when we can. We all love you Francis