by Richard Mallory Allnutt

Few could dispute the Hawker Siddeley Harrier’s place as one of the most iconic military jets of all time. In terms of fixed-wing attack aircraft, this diminutive ‘jump-jet’ was unique in the western world, until the advent of the Lockheed F-35B, for its ability to take off and land vertically and transition from a hover to conventional flight. Harriers have served with distinction in various air arms across the world since the late 1960s. They earned their spurs in combat during the Falklands War of 1982, and are still in action on the front lines today.

The type has been popular on the air show circuit as well, earning awe from onlookers wherever she appears. Who could forget the type’s signature air show maneuver; the Harrier taking off vertically – hovering – and then raising her nose gracefully upwards until pointing straight up for an ascent into the heavens? And for her finale following a vigorous beat up of the field, the Harrier would return to hover in front of show-center, dipping her nose in a last bow to the crowd, before settling to earth once more.

Despite the Harrier’s success, both commercially and in combat, the entire design almost failed to reach maturity. Indeed, if it hadn’t been for the cooperation between the UK, USA and West Germany during the early 1960s in developing the aircraft’s forebear, the Hawker-Siddeley Kestrel, it is doubtful the type would have made it past the prototype stage. Britain was in desperate financial straits following WWII and lacked the political fortitude to press ahead alone with many promising projects, cancelling a number of high profile domestic ventures such as the BAC TSR2.

The Kestrel itself was a development of the Hawker P.1127 concept aircraft, which married the pioneering Bristol Pegasus, vectored-thrust jet engine with a brand new airframe designed around it. Just six P.1127s and nine Kestrels rolled off the production line at Hawker’s development site in Kingston-upon-Thames. The test flights took place at Dunsfold Aerodrome, with the first being a tethered hover of P.1127 XP831 on November 19th, 1960. Such was the radical nature of these aircraft that a number were involved in accidents during testing. Even so, about half of the fifteen prototypes/development aircraft survive in one form or another. And we are happy to see that one of these historic airframes, following decades of abuse and neglect, has finally found a new home where she has begun to receive the love and care she so deserves.

This example is Hawker Siddeley Kestrel FGA.1 XS694. The Wings Museum, near Balcombe in West Sussex, England, acquired her from a private collector in the USA. The forlorn jump-jet had seen use as an attraction/obstacle in a paintball park, and was in a desperate state. While the purchase took place back in July, 2018, this wasn’t open knowledge. The museum kept this development quiet until fairly recently, because of concerns relating to a proposal for construction of a new museum building at the former Dunsfold Aerodrome, site of the Kestrel’s first flight. After a protracted period of tense negotiations with the local council, the Wings Museum finally received permission for the new building, and now feels free to announce the acquisition of XS694 – and her eventual return to Dunsfold!

XS694 first flew from Dunsfold on December 10th, 1964. A little over a month later, on February 8th, 1965, she became the first Kestrel to join the Tripartite Evaluation Squadron (TES) at RAF West Raynham in Norfolk. Three countries, the USA, UK and West Germany, were involved in testing the Kestrel’s suitability to fulfill a proposed NATO requirement for a VSTOL (Vertical Short Take Off and Landing) combat aircraft. Each nation received three Kestrels apiece, although following the satisfactory completion of TES testing in November, 1965, West Germany opted out of the program (however, they did develop prototypes in parallel for a VTOL transport , the Dornier Do 31, which used a pair of Bristol Pegasus engines). The three West German Kestrels reverted to US ownership, and joined the three original American examples in the USA for further testing. XS694 arrived at Eglin AFB in Florida, USA during January, 1966, where she became XV-6A 64-18268 with the U.S. Air Force. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) had been instrumental in assisting P.1127 and Kestrel development, performing wind tunnel tests, and other duties, since the early days of the program. They requested a pair of Kestrels for testing themselves, with XS694 being one of them. She moved up the U.S. east coast in July, 1966 to join NASA’s fleet at Langley Field in Norfolk, Virginia. Here she became ship 520 in NASA livery.

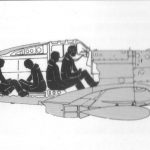

Unfortunately, XS694 suffered an accident a year later on August 27th, 1967. According to Lee H. Person Jr.’s incident report, the legendary NASA test pilot was ferrying the Kestrel out to NASA’s test facility on Wallops Island to evaluate the GSN-5 approach radar on that fateful day. During the landing roll-out, the aircraft developed a severe list to the right while also yawing sharply left. A photographer, filming the landing for NASA, was in the Kestrel’s likely path as it headed off the runway and appeared momentarily unaware of his predicament. This distracted the pilot briefly, who applied further undercarriage steering input (the two main gear could be swiveled) in an attempt to avoid him. The photographer ran for his life, as the Kestrel swerved off the runway, effectively in a ground loop. The starboard wing outrigger ripped away from the airframe as it slid sideways through the grass. As XS694 lurched to a halt, the right forward fuselage struck the earth and partially crumpled the nose, but thankfully the aircraft came to rest upright without rolling over. However, upon pulling his canopy release, the cable failed, and Lee Person could only get free of the airframe after the fire-rescue team smashed the canopy, allowing him to crawl out. While the Kestrel was largely intact, the damage was such that NASA deemed her beyond economic repair, relegating XS694 to become a parts source for the other Kestrel then in its fleet: NASA 521 XS689/64-18263.

NASA received XS692/64-18266 as a replacement for XS694; the airframe gained the latter’s 520 tail code in the process. Interestingly, there is clear evidence that XS694 swapped wings with XS689 at some point, although there is no published data which identifies exactly when this happened. Logic suggests that it occurred before XS694 had her accident though – perhaps during reassembly when the aircraft first arrived for testing from the UK. Happily, all three of the ex-NASA Kestrels survive today: XS692 is on display at Air Power Park, in Hampton, Virginia, and XS689, while belonging to the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum, is hanging from inside the in Chantilly, Virginia). Somehow, XS694 survived over the years, suffering damage to her airframe and her dignity at almost every step. But finally she is now home in the UK with a much brighter future at the Wings Museum.

Almost as soon as the aircraft was uncrated at the Wings Museum, a restoration team got to work on the airframe, assessing what was needed to make her whole again. The museum acquired an early variant of the Pegasus engine in a trade with the Gatwick Aviation Museum, a cockpit canopy from the Boscombe Down Aviation Collection and even some original Kestrel drop tanks from the Brooklands Aviation Museum.

Aaron Simmons, the project’s leader recently stated, “I am very excited to finally be making a positive start on this unique and rare airframe; knowing it will eventually be on display at Dunsfold makes the project all the more satisfying. We have made some great leaps forward with the project using the latest CAD drawings packages to have the front cockpit bulkhead frame laser cut to replace the damaged one. We have also had a set of pilots instrument panels produced and are making some great progress on collecting the instruments needed to populate the panels but there are still many items needed.”

There are still many missing parts, including the undercarriage, which they would like to obtain. In addition, the wing was sawn in half at some point relatively recently and will obviously need significant repairs. Thankfully, an engineer who worked on the Harrier program is lending assistance in this area. Currently, work on the project has slowed somewhat, hampered by the restrictions necessitated with the Coronavirus pandemic. However, Aaron Simmons has the cockpit section at his premises and is working hard to restore a lot of its components. We will be reporting further on his work in the coming weeks.

In the interim, the museum would like to hear from anyone who may be able to help with the project in any way. The team would also like to make contact with anyone who knows more about the aircraft’s history, or who worked on ‘694, whether in the UK or USA. They are obviously also keen to hear from anyone who might be willing to sponsor the project, or provide donations to help fund the restoration. It will be marvelous to see her finally back in one piece again, displayed proudly at her first home in Dunsfold. The Wings Museum should be congratulated for their efforts thus far – here’s to a much brighter future for this important aircraft!

You can follow the restoration on facebook HERE.