As many readers will know, Australia’s Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation (CAC) designed and built a number of different airframes based upon the North American Aviation NA-16, a trainer which eventually evolved into the legendary T-6 Texan/Harvard. The Wirraway was one of CAC’s more successful designs. A number of different Wirraway variants evolved, some of them armed, but the type primarily served in the training role within Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), a function which it performed admirably between 1939 and 1959. While CAC built more than 750 Wirraways at their factory in Fisherman’s Bend, near Melbourne, Victoria, the type is pretty rare today, with fewer than two dozen survivors in any recognizable form today, and of these, just a handful are presently capable of flight. This is why the recent news of Rodney Knights’ expedition to recover the substantial remains of a Wirraway from Lake Corangamite near Melbourne, Victoria is such welcome news. The aircraft in question, CA-16 A20-714, had lain more or less embalmed in these muddy waters since October 20th, 1950, when RAAF trainee pilot, Vance Drummond ditched the Wirraway during an instructional flight with No.1 Flying Training School from Point Cook, Victoria.

The following story, as related by Rodney Knights to our longtime antipodean correspondent, Phil Buckley, describes A20-714’s history, her pilot and his accident and, of course, Knight’s subsequent recovery of the Wirraway some seven decades later…

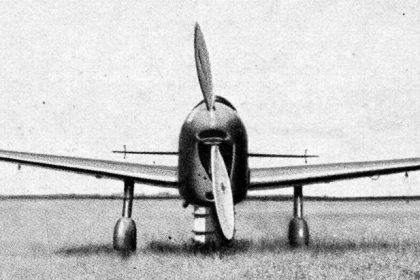

CAC CA-16 Wirraway A20-714

CA-16 A20-714 was one of 755 Wirraways which CAC built at their factory in Fishermans Bend, Melbourne. It rolled off the production line during the early summer of 1945. The RAAF formally accepted the trainer on July 9th, 1945 with the aircraft initially going into storage with No.1 Aircraft Depot (AD) at RAAF Station Laverton near Melbourne. No.7 AD took her on strength the following month at Tocumwal, but the airframe continued in various categories of storage until receiving an upgrade to Cat C Special Reserve in July, 1946. The aircraft saw its first active use with No.1 Flying Training School (FTS) after arriving there on May 21st, 1948. Accident 1100 hrs 05/11/48 when aircraft made a precautionary landing at Echuca due to engine cutting out in flight. On November 5th, 1948 the aircraft made a precautionary landing at Echuca due to an in-flight engine failure with F/Lt P.W. Symons and F/Lt W.D. Ephgrave aboard; neither were injured. Repaired soon after, the aircraft returned to service in its training role.

Vance Drummond

Vance Drummond originally came from Hamilton, New Zealand, being born there on February 22nd, 1927. By the time WWII arrived, Vance was still too young to ‘do his bit’ unlike his older brother, Frederick, who joined the RAAF (and, sadly, later perished). Vance had to wait until May 1944 before he could enlist in the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF), training to become a navigator. He graduated with the rank of Sergeant in September 1945, but with the war now over, the RNZAF no longer needed his services, discharging him that October. Vance, still looking to serve his nation, joined the New Zealand Military Forces in March 1946. A few months later, he found himself part of J Force, New Zealand’s contribution to the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Japan. In October 1948, Vance returned home, seeking a transfer to the RNZAF where he hoped to become a pilot. Oddly, the RNZAF considered him too old for such a slot, even though he was just 21! Despite this rejection, Vance persisted with his aeronautical ambitions, having better luck with the RAAF, who accepted him for flight training in August, 1949.

Lake Ditching

By the fall of 1950, Drummond was well on his way to becoming a pilot with No.1 FTS at RAAF Point Cook. Trainee pilots would often conduct their practice flights above nearby Lake Corangamite due to its lack of obstacles, and it was over this location, on October 20th, 1950, that Vance met with an accident while flying Wirraway A20-714.

Vance departed RAAF Point Cook at 9:48 am on the fateful training flight. By 10:30am, Vance was conducting a low level solo flying exercise over Lake Corangamite, traversing the waters at altitudes ranging from 50 to 200 feet. While still over the lake, Drummond adjusted his compass setting, but accidentally nudged his control column in the process, causing the Wirraway to dip slightly, its propeller tips striking the water. Drummond immediately attempted to gain altitude, but the now-bent propeller caused such violent vibrations that Vance realized he had no option other than a forced landing. The pilot quickly prepared his Wirraway for ditching, locking his canopy open and gently lowering the aircraft, in a tail-down attitude, onto the lake’s surface. The trainer then splashed into the lake with some force, Drummond suffering slight injuries when his face struck the cockpit deck panel.

A witness, Harry Hynes, described his view of the accident, stating: “A sheet of water leapt 40 feet into the air, and there was a terrific crash.” The aircraft came to a halt rapidly and began sinking. A20-714 soon settled into the murky shallows, digging into the muddy bottom beneath 8 feet of water. Drummond, still in the cockpit, struggled for some two minutes underwater to escape his seat and parachute harness. Reportedly, after his rescue, he stated: “My lungs were almost bursting when I freed myself.” After extricating himself, Vance was still some 800 feet from the shoreline and encumbered by his bulky flight clothing. To keep his head above water, the pilot clung to his Wirraway’s tail, which still protruded above the surface. Meanwhile on shore, Pat Hynes, Harry’s brother, saw the pilot’s predicament and rushed out into the lake atop a horse to attempt a rescue. But the horse struggled in the water and gloopy mud, thwarting this plan. Pat then rang the local police station, hoping they could quickly arrange for a boat to arrive. While awaiting his salvation, Drummond stripped down to his underclothes in case the plane sank any further and he needed to swim for shore. He remained clinging to the Wirraway’s tail for another two hours before the police were able to haul him aboard a boat they retrieved from Camperdown. An RAAF post-crash investigation determined that, although Drummond was technically at fault, there were outside contributing factors such as the “glassy” nature of the lake’s surface (making altitude hard to determine visually) and the awkward position of the Wirraway’s compass. While Vance Drummond earned a reprieve which allowed him to continue with his flight training, the Wirraway was obviously in a tighter spot. The RAAF wrote off the airframe, ordering its “conversion to parts” on January 22nd, 1951. With much of the airframe now buried under mud, however, its recovery was economically impractical at the time. While a crew did remove the Wirraway’s vertical tail assembly on February 6th, 1951, the rest of the airframe was left where it lay, essentially forgotten about… until 2005.

Drummond’s Post-Crash RAAF Career

Following his ditching incident in A20-714, Vance continued his RAAF flight training, graduating – first in his class – as a sergeant pilot in February, 1951. Posted to RAAF Williamtown in New South Wales, Drummond joined No.78 (Fighter) Wing which was then operating the iconic North American P-51 Mustangs alongside the RAAF’s first generation jet fighter, the de Havilland Vampire. By June 1950, RAAF pilots were involved in the Korean War. In August, 1951 Drummond received orders to join No.77 Squadron, then flying Mustangs in combat out of Kimpo in Korea. By the time he arrived at Kimpo, the squadron had transitioned to the Gloster Meteor F.8.

No.77 operated over Korea, flying as far as the Yalu River in conjunction with US Air Force F-86 Sabres. Their missions involved a mixture of combat air patrols and bomber escorts, shepherding American B-29s. On December 1st, 1951, Vance Drummond was flying as part of a formation of twelve RAAF Meteors when they were attacked by a superior force of Soviet-manned MiG-15s. Three Meteors fell to the MiGs that day, including Drummond’s. Drummond ejected from his stricken jet fighter, floating down behind enemy lines where North Korean troops captured and imprisoned him. In April 1952, Drummond and four fellow Prisoners of War escaped their camp, only to suffer recapture two days later. Vance suffered a beating for his part in the escape, along with a month in solitary confinement. Following the armistice announced on July 27th, 1953, formal combat came to an end in Korea, and this allowed the exchange of POWs by both sides. Drummond gained his release on September 1st, 1953, and found his way back to Australia soon afterwards.

Upon his return to Australia, Drummond continued his RAAF career, taking part in the 8 Advanced Navigation Course. In April 1954, he was one of six navigators in Avro Lincoln bombers who made a graduation flight from East Sale, Victoria to New Zealand. Vance then received a posting to No.2 Operational Training Unit (OTU) at RAAF Williamtown for flying duties where he undertook the No.3 Fighter Combat Instructors Course.

In November, 1954 the RAAF established the Sabre Trials Flight (flying CAC-built variants of the North American F-86 Sabre) as part of No.2 OTU; Drummond was a founding member. On May 30th, 1955, Drummond received a promotion to the rank of Flight Lieutenant. In 1959, Drummond joined RAAF Headquarters Operational Command at Glenbrook, New South Wales. Two years later, he entered the RAAF Staff College in Canberra, receiving a posting upon matriculation in 1962 as a Flight Commander with No.75 Squadron and, soon after, a promotion to Squadron Leader. The squadron flew CAC Sabres and fielded the Black Diamonds aerobatic display team. This team appeared at events across Australia, showcasing both the Sabre and the RAAF’s flying prowess to the public. By October 1962, Drummond was leading the Black Diamonds.

In December 1964 received another posting, this time to Canberra where he joined the staff at the Department of Air. In December 1965 he gained promotion to the rank of acting Wing Commander, and was soon in Saigon, South Vietnam on secondment to the US Air Force’s Second Air Division. His primary role in Vietnam was to observe American methods for aerial transport, reconnaissance, ground attack, and defense. By July 1966, he put in a request to join the US Air Force’s 19th Tactical Air Support Squadron as a forward air controller (FAC), flying the Cessna O-1 Bird Dog. FACs had a significant, though highly risky role. They would fly low over enemy territory searching for enemy ground targets, such as troops or high-value structures, and then guide strike aircraft to attack these targets. They would often follow up on missions, assessing their outcomes. Drummond had the distinction of being the first in a number of RAAF personnel to serve as FACs with the USAF during the Vietnam War. By October 1966, concluded his tour as a FAC, having a tally of 381 sorties and several awards.

In January 1967, Drummond received a promotion to Wing Commander, taking command of No.3 Squadron in the month following. The squadron had recently returned to RAAF Williamtown from overseas duty at RAAF Butterworth in Malaysia. The unit soon began transitioning to the brand new Dassault Mirage III-O. In April 1967, Drummond began his conversion to the type, entering the No.9 Mirage Course with No. 2 Operational Conversion Unit (OCU). On May 17th, Drummond was flying on a training exercise at high altitude with 3 other Mirages some 90km off the coast north east of Williamtown. Sadly, this flight was to be Drummond’s last; without explanation, his Mirage fell out of formation suddenly and dove into the ocean. Although neither his body nor the airframe were ever recovered, there was strong circumstantial evidence from his widow, Margaret, during the subsequent court of enquiry, that Vance may have suffered a mid-flight heart attack, causing the crash. Vance Drummond was only 41 at the time of his death, a highly experienced and capable leader; the RAAF awarded him a posthumous Distinguished Flying Cross.

The Rediscovery of Wirraway A20-714

As already mentioned, the RAAF recovery crew did remove some components from Drummond’s Wirraway soon after the crash, but left most of the airframe sitting where it had fallen. The wreck sank further into the mud over the succeeding decades, presumably forgotten forever.

In 2005, however, a Colac-based crop-duster named Gordon Wilson spotted the remains in the lake during one of his sorties, rekindling the chance for its recovery. Rodney Knights, a local resident first learned about the Wirraway wreck from an archaeologist. Knights has a keen interest in vintage military aviation, which included volunteering with Pierce Dunn’s Warbirds Aviation Museum at Mildura Airport during the 1980s. He had also spent time as a commercial salvage diver and developed a working relationship with Heritage Victoria following various collaborations with the organization, so in many ways, he was ideally equipped to take on the challenge of recovering the Wirraway.

Knights surveyed the wreck and determined that some 70% of what remained sat below the mud, and appeared to be in good condition. Whatever lay above the mud, however, had deteriorated significantly due to the lake’s significant salinity. He noted that others in the area had expressed interest in removing the Wirraway from the lake, but their efforts had not progressed far at that point. Not wanting to tread on any toes, Rodney decided to shelve his own endeavors, to allow others the opportunity to raise the Wirraway. However, he used the interim to formulate a plan for his own recovery, should the opportunity arise.

Knights Plans the Recovery

In the end, no one else stepped forward to save the Wirraway, so Rodney decided that he should take on the challenge. Rod was still in his 40s at this point, and knew the restoration would be a longterm proposition. Nevertheless, he was determined to see it through. Before he could even begin executing his plan to retrieve the airframe, however, Rod knew that he would need formal permission from a number of different parties. He began the process by approaching the various potential stakeholders, a list which eventually totaled twelve different entities including the RAAF, Worksafe Victoria, Corangamite Shire, Corangamite Catchment Management, Aboriginal affairs, Victoria Heritage and of course the EPA. Not all of these organizations liaised easily with one another either. The biggest problem centered around the crash site’s location, as it lay in an environmentally delicate heritage area – this would have a significant impact upon any recovery plans.

Rod had to undertake numerous studies on the lake’s ecology, including a review of bird life at the lake covering the previous 50 years. The specific content required for this report took a lot of juggling back and forth between Rod and the agency in question. Part of the permit’s conditions included a comprehensive study of the bird life at the lake, but Rod’s team could only visit in wintertime, with a window between March and August each year, so as not to disturb the birds while they raised their young. However, visiting the lake in winter meant that Rod’s team would have to traverse a lot of boggy ground, making travel to the lake quite a task. Of course, Rod also had to provide a study of the flora and fauna around the lake’s edges and nearby land. Another study required investigating any potential impact which the recovery might have on local farming land engaged in Rod’s recovery strategy. He also had to employ a shipwreck archaeology specialist to perform a study of the entire lake, to make sure no other historical sites would be affected. The Victoria Heritage permit approval process seemed to drag on and on… Another required survey involved a complex analysis of the mud and water in and around the submerged airframe, to make sure that digging up the aircraft wouldn’t expose excessive toxins to the local environment. Despite all of the obstacles and the length of time involved, Rodney made continued progress. The first big breakthrough came in 2011, when the RAAF granted Rod both ownership and permission to recover the Wirraway. He also received approvals from all three Aboriginal groups which supported him rescuing the aircraft. In the end, it took Rod 12 years to obtain all of the assorted local and national Government permits to raise the Vance Drummond’s Wirraway.

From his careful pre-planning, Rodney Knights knew that getting heavy machinery down to the lake and out to the crash site would pose a significant challenge. The Wirraway was situated some 800 metres offshore, but this could vary significantly with lake levels, especially during periods of heavy drought. Rod’s recovery methodology had to account for all potential situations. Looking for the most efficient way to rescue the Wirraway, Rodney designed and built some specialized equipment for the purpose. Due to the typically soggy state of farming terrain during local winter conditions, Rod’s team had to move all of their tools and gear to the lake by hand and then travel to the crash site in small boats. While awaiting permit approvals, Rod had used the downtime to build some of the recovery equipment he would need. This included construction of a lifting frame which he could bolt to a barge to raise the aircraft from the water. His plan was to construct a platform around the aircraft and use a gantry system to carefully extract it before placing the fuselage and wings into fresh water pools. However, due to the massive amount of time involved in the planning and permit process, some of the assorted permits expired and he had to be reapplied for. And them the onset of the pandemic in early 2020 added extra delays to the recovery effort. Given the arduous permit requirements needed to salvage this Wirraway, it is unsurprising that none of the other 19 submerged aircraft wrecks in Victoria have been recovered so far…

2021 Recovery!

While Lake Corangamite is shallow, being typically no more than 2 meters deep, it is the largest such body of water in Victoria, and located in the Australian state’s western district some 25km from Colac. Water levels are seasonal, however, and the hot summer months can even dry it out completely. The poor Wirraway had sat in an alternating wet and dry environment for over 60 years, enduring the lake’s high saline content and acidity. When it first re-emerged in 2005, the airframe sections which showed above the mud were in relatively decent condition, but corrosion damage had accelerated in the intervening years. Oddly though, the sections of airframe resting below the mud in an anaerobic environment gained a red bacterial crust, a concretia if you will, which seems to have slowed down further damage.

Finally, in August 2021 a window opened for Rod and his team to recover the Wirraway. Early that month, they undertook the first small scale recovery effort, salvaging some test components, such as the elevators, to gain greater understanding for how complex the rest of the recovery process would be. This endeavor persuaded Rod that the airframe was generally intact and salvageable. The next step involved raising the propeller and engine to the surface, which they achieved successfully. Rod and his volunteers then began the next recovery goal, which involved lifting the fuselage using the steel gantry system he had devised. They accomplished this step successfully during the last two weeks of August, 2021. Of course, there were some complications due to wind and the need to remove the bolts holding the fuselage to the centre section, but these didn’t cause too significant a delay. Once the fuselage was raised, the team placed it onto the barge and towed it to shore.

At this time of writing, the condition of the wings cannot be determined easily under the water. They could be damaged but Rod does not know yet. The Wirraway’s wings and centre section are set to remain in the lake, for now, awaiting retrieval at a later date. Due to lake access ending with the antipodean winter at the close of August 2021, further recovery missions will next be able to take place in March 2022, when the permits will again allow access. So far, Rod has moved the recovered engine and fuselage into a controlled environment – a set of above-ground fresh water pools with a slightly alkaline pH to both desalinate and minimize further corrosion. This will be a longterm process, and Rod is receiving advise from a top corrosion expert on the best practices to apply in this first stage process.

Restoration Plans

Rod and his team have moved the Wirraway to Lethbridge Airport in south east Victoria. Here they will begin the arduous process of restoring the aircraft back to airworthy condition. Once out of the fresh water pools, the first step will involve dismantling the airframe into components. This will enable Rod and his team to inspect, treat and restore each component and section as and where possible. Rodney is also preparing the groundwork for the step-by-step process of returning the Wirraway to flight status – an ambitious, long term goal. While they have found no original photographs of the aircraft during its service life, based upon residual evidence still present on the airframe, Rod believes the Wirraway wore an overall yellow paint scheme at the time of its crash, but he may choose to restore the aircraft in an overall silver scheme. He has tentatively chosen to nickname the aircraft Corangamite Siren.

Many thanks to Rodney Knights and Phil Buckley for this story, and to Jonn Stewart for the recovery photos. Here is hoping that Rod and his team succeed in retrieving the Wirraway’s wings next March, and that the restoration can begin soon after!