On this day, the 75th anniversary of the Attack on Pearl Harbor, we at WarbirdsNews thought our readers would be interested in learning more about a largely forgotten target of the Japanese forces that infamous Sunday morning: Marine Corps Air Station Ewa. The base played a pivotal role in prosecution of the Pacific War in the years that followed December 7th, 1941, but it closed within a decade of the war’s conclusion. Though long deactivated, some significant structures still exist at the site even now, and there are ongoing efforts to save them. This article will relate some of MCAS Ewa’s history, and also what remains today…

Ghosts of Pearl Harbor: Saving the Crossroads to Marine Aviation in the Pacific Theater

Words: by Matthew McDaniel

Images: via The US National Archives, except where noted

The scene was utter chaos as shocked witnesses ran for cover from the machine gun fire of strafing aircraft. Japanese Zero fighters, Val dive-bombers, and Kate torpedo-bombers screamed back and forth overhead. While their primary targets were mostly naval vessels in and around Pearl Harbor, any “targets of opportunity” were under equally deadly and immediate threat. Such targets included the four dozen military aircraft parked at Marine Corp Air Station (MCAS) Ewa, located 7 miles west of Pearl Harbor. Ewa was not among the several large military air bases on O’ahu specifically targeted in the two-wave Japanese attack. However, being nearby and directly under one of the aggressor’s flight paths to Battleship Row made it an easy target. So easy, in fact, that the aerial assault on Ewa actually preceded the attack on Pearl Harbor by two minutes. Ewa’s inventory of Marine Corps aircraft was virtually annihilated.

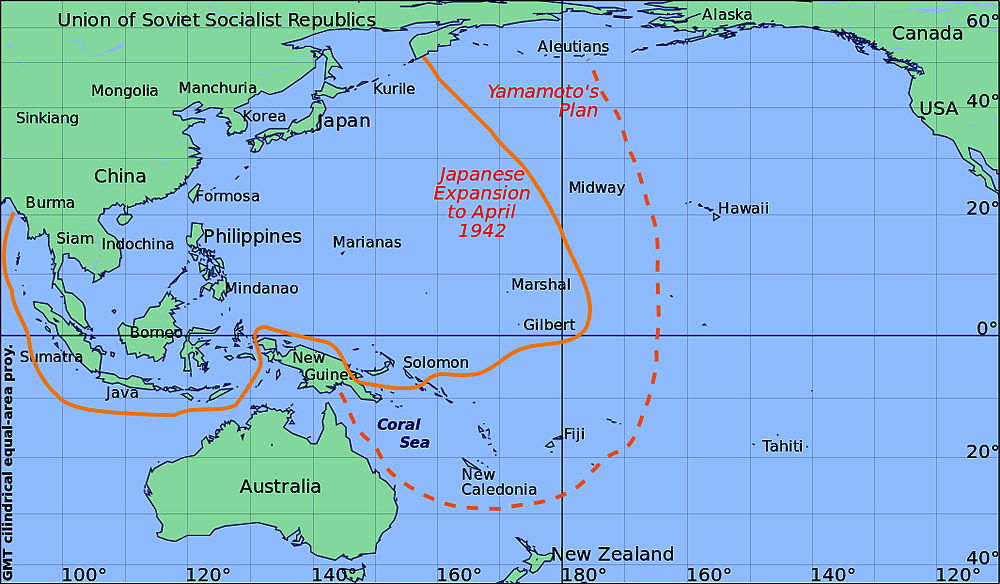

In spite of the destruction that rained down upon MCAS Ewa that Sunday morning, the base proved immediately vital, and remained so throughout America’s involvement in WWII. This was especially true for the naval battle historians consider to be America’s direct response to Pearl Harbor. The epic clash of carriers which became known as the Battle of Midway is widely accepted as the most important engagement in U.S. naval history. By sinking all four of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s major aircraft carriers, the Allied victory at Midway greatly diminished Japan’s ability to wage offensive war in the eastern Pacific. This in turn insulated the Hawaiian Islands from further enemy attack, allowing them to rapidly become the primary staging point and training ground for military personnel and equipment headed to the Pacific Theater’s war zones. However, MCAS Ewa’s important contribution to the astonishing success of Allied forces in the waters and skies near Midway Atoll is now largely forgotten. Ewa became the crossroads for Pacific Theater Marine Corps Aviation. Today, 75 years after Japanese aircraft riddled MCAS Ewa with bullets, many historical reminders of its role in the build-up to the Battle of Midway remain. Sadly, a good number are undocumented, most are unprotected, and some are facing the imminent threat of destruction from urban encroachment.

Ewa Development: 1925 through 1941

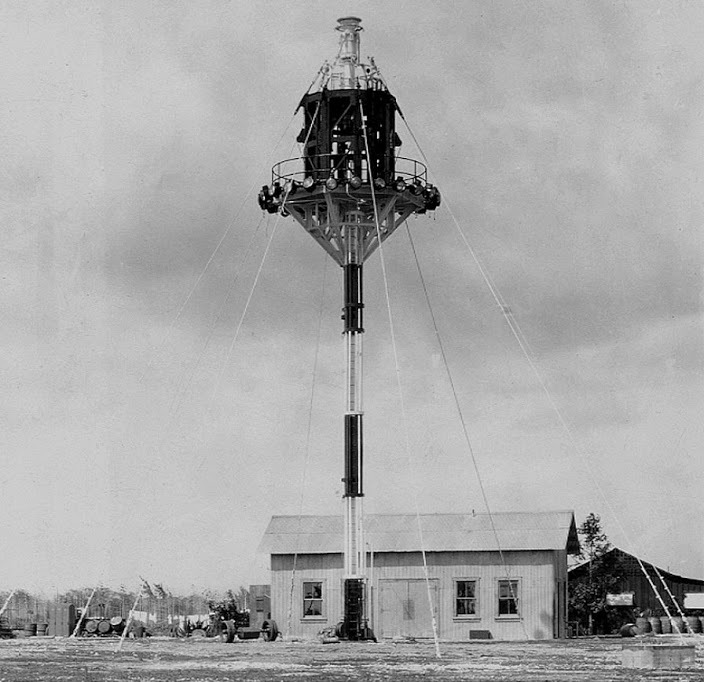

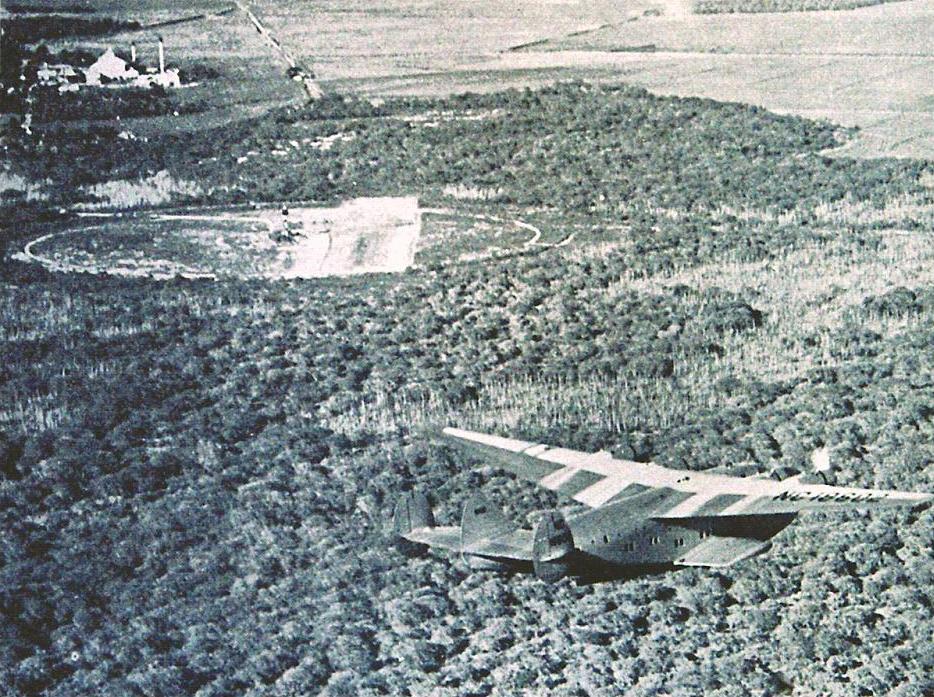

Ewa Mooring Mast Field opened in 1925 as a base for dirigibles (rigid airships), complete with a 100-foot mooring mast centered inside a 2,000 foot wide, cleared circle. The mast met the specifications for docking the USS Shenandoah. Sadly, the massive airship crashed in Ohio (with the loss of 14 crew) on September 3rd, 1925, before she could make the Pacific crossing to Hawaii. The mooring mast remained intact and unused until 1932 when the US Navy had it shortened by 50-feet to accommodate the sister-airships USS Akron and USS Macon. But both vessels had crashed by 1935 before either could launch for Hawaii, and their losses effectively brought the US Navy’s dirigible program to an end.

Though never used for its intended purpose, the mooring mast remained standing, becoming a navigational landmark. Construction crews built a 1,500′ emergency airstrip nearby the mast, and military squadrons from neighboring bases would often regroup overhead. Even the famous Pan Am Clippers used the mast as a navigational fix.

Eventually, the Navy saw more potential for the area. They bought 3,500 acres of adjacent land for the purpose of Naval and Marine flight operations in September 1940. Concurrent to Ewa’s reconfiguration as a Marine Corps Air Station, the US Navy was developing the opposite end of the same property into what would eventually become Naval Air Station (NAS) Barbers Point. MCAS Ewa was commissioned on February 3rd, 1941.

While officially operational, MCAS Ewa was still in a very primitive state, with Marines living in tents rather than barracks and the crow’s nest atop the mooring mast serving as the Air Station’s control tower. But, by late November 1941, enlisted troop barracks and officer’s quarters were completed, along with a second runway and other infrastructure. The tranquility would last for barely a week.

Under Attack: Dec. 7, 1941

In a fatal irony, the old mooring mast proved useful as a navigation aid to the enemy as well. Attacking Japanese aircraft on that ‘Day of Infamy’ used the tower as a rendezvous point, strafing Ewa’s runways, aircraft, equipment, and personnel as they passed overhead. They met with little resistance, as the best defensive measures against enemy aircraft that those at Ewa could offer were pot shots with pistols and Springfield rifles. After hitting various targets on O’ahu, Japanese aircraft would again rendezvous over the Ewa mast, expending any remaining ammunition upon the base, before returning to their awaiting carriers. Four Marines and two civilians were killed during the assault on Ewa, and 13 Marines were wounded. While no Ewa-based aircraft were able to defend their home, two US Army Air Corps P-40’s from Haleiwa Airfield did engage the Japanese over Ewa.

MCAS Ewa’s aircraft belonged to Marine Air Group 21, Squadrons VMF-211, VMSB-231, VMSB-232, and VMJ-252. The list of damaged or destroyed airframes included:

- Grumman F4F-3 Wildcats (11)

- Vought SB2U-3 Vindicators (8)

- Douglas SBD-1 & -2 Dauntless’ (23)

- Two Grumman J2F-4 Ducks

- A Lockheed JO-2 Electra Junior (aka: Lockheed Model 12)

- A Sikorsky JRS-1 (Not to be confused with the USN Pearl Harbor attack veteran JRS-1 now preserved by the Smithsonian).

- Two Douglas R3D-2’s (Douglas only built twelve DC-5’s and four became Marine R3D-2 paratroop transport variants. These two were both repaired and returned to service).

- A North American SNJ-3 Texan

Of these 49 aircraft, 33 were destroyed while 16 sustained serious damage. The base’s emergency response vehicles were badly shot up too. While Ewa had suffered terrible punishment, their losses paled in comparison to those wrought at Pearl Harbor and other military bases across O’ahu. Because Japanese aircraft passed over Ewa on their way to bomb their primary targets or upon returning, few had spare bombs to drop on Ewa. Thus, while the enemy strafed Ewa heavily throughout the morning, igniting fires across the base, the runways and ramps remained operational afterwards, and free of bomb craters. Leaving Ewa’s infrastructure relatively intact was a seemingly small miscalculation, but the base proved critical to protecting and operating the few combat aircraft that remained airworthy. Ewa became ground zero for the rapid resumption and intensification of the build-up of America’s Pacific aviation fighting force.

Desperate for Cover

Clean up at Ewa began immediately. Other O’ahu airfields were severely damaged and many offered little in the way of cover for their remaining aircraft. Everyone expected Japanese forces to make additional attacks on the Hawaiian Territory, so protecting the few remaining aerial assets was a high priority. No aircraft revetments yet existed at Ewa, but the air station offered two advantages: two useable runways and natural camouflage from nearby high grass and dense stands of Kiawe trees. Aircraft deemed repairable were immediately pushed into the undergrowth and covered with palm leaves, branches, tarps, nets, or anything else at hand. An Army pursuit (fighter) squadron moved in too, awaiting repairs to their home runways at Wheeler Field. Crews laboring to build neighboring NAS Barbers Point were reassigned to expand Ewa, which included enlarging the two existing runways while adding two more.

In early 1942, within weeks of the attack, construction began on what would soon total 75 aircraft revetments at Ewa. The earliest shelters were simply piled sandbags plastered with stucco. Aircraft access was via crushed coral taxiways and asphalt aprons. Strangely, many of these original revetments survive in better condition than their later, sturdier counterparts. The first domed revetment in Hawaii appeared at Ewa and several geometric variations followed. Many of them survive in amazingly good condition for their age; some relatively easy to access and some buried in dense vegetation. All remaining revetments have one thing in common; they hid and protected aircraft bound for the Battle of Midway.

Destination: Midway Atoll

Even before the Japanese attack, Marine pilots had already deployed from Ewa to Wake and Midway Islands, as well as the carriers. Those who remained were the first members of newly-organized squadrons as more men and replacement aircraft arrived following the surprise attack. Throughout the first half of 1942, a steady stream of Marine aviators, mechanics, and support personnel passed through Ewa during the buildup for Midway. Many of the aircraft Marines flew were US Navy castoffs. The Marines flew whatever was available, including some dangerously outdated types like the Brewster Buffalo and Vought Vindicator. At Midway, the Ewa Marine pilots fought against many of the same Japanese aircraft and crews that had attacked Ewa and Pearl Harbor six months earlier. The first Medal of Honor of WWII went to Ewa pilot Capt. Henry Elrod, USMC, for heroism in defense of Wake Island. The only Medal of Honor resulting from the Battle of Midway was also bestowed upon an Ewa pilot, Capt. Richard Fleming, USMC, who attacked the Japanese cruiser Mikuma while flying a Vought SB2U Vindicator dive-bomber.

After the U.S. victory at Midway, MCAS Ewa continued to transition an ever-increasing wave of Marine and Naval aviators and aircraft between arrival from the mainland and their Pacific combat postings. In fact, nearly every WWII Marine Corps aircraft or aviator passed through MCAS Ewa!

At the conclusion of hostilities, Ewa did the opposite, out-processing aviation personnel and deactivating marine and naval aircraft.

Decommissioned

On June 18th, 1952, one decade and two weeks after Ewa pilots contributed to the stunning success at Midway, MCAS Ewa officially closed. Korean War-era jets demanded longer runways than those at Ewa and extensions were infeasible, due to the close proximity of NAS Barbers Point. So Ewa’s land became part of Barbers Point, while maintenance of its aviation infrastructure stopped (including the historic revetments). The buildings disappeared.

Except for their brief use in the 1970 film Tora! Tora! Tora!, Ewa’s revetments and place in history were largely forgotten. Nature reclaimed the old air base. The Navy decommissioned NAS Barbers Point in 1999 and it became the civilian airfield now known as Kalaeloa Airport, John Rodgers Field (PHJR).

Preservation

Around 2007, Ewa historian John Bond discovered that much of MCAS Ewa still existed, hidden under thorny trees and thick overgrowth. By 2013, pressure was mounting for the Navy to release the former MCAS Ewa & NAS Barbers Point acreage for residential and commercial development projects. Far too many historical areas, structures, and artifacts have already been lost. However, Mr. Bond, his team, and others have been working diligently to prevent further losses, hold off developers, and get Ewa and its revetments the protection, recognition, and preservation they deserve via State and National governmental programs and services. While those fights are far from over, progress thus far includes:

- The entire 1941 Ewa airfield (appx. 175 acres) has been placed on the National Register as a Battlefield. Unfortunately, this area does not include the entire MCAS Ewa, and thus excludes the early 1942 revetments built immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack.

- The later 1942 concrete dome revetments have been identified in a Navy Base Realignment & Closure document as “eligible” to become a National Historic District. This has not, however, actually happened as of this writing.

- The Ewa Battlefield is considered the larger area around and above the Ewa airbase where a battle was fought on U.S. soil on Dec. 7, 1941. This Battlefield was placed on the Hawaii State Historic Register in Nov. 2015 and on the National Register in May 2016.

- A National Park Service Battlefield protection program grant was recently awarded to identify and list some of the concrete dome revetments. However, not all are currently included, nor are the earlier sandbag and stucco revetments, which still stand but remain under threat.

For more information or to contribute information or assistance in preservation measures, visit these websites and blogs:

http://ewafield.blogspot.com/

https://www.facebook.com/Save-Ewa-Field-270728152937385/

https://www.nps.gov/places/ewa-plain-battlefield.htm

https://www.nps.gov/abpp/grants/battlefieldgrants/2016grantawards.html

http://ewa-battlefield-nomination.blogspot.com/

About The Author: Matthew McDaniel is a Master & Gold Seal CFII, ATP, MEI, AGI, & IGI and Platinum CSIP. In 26 years of flying, he has logged 16,000 hours total and over 5,500 hours of instruction-given. Currently, he flies the Airbus A-320 series for an international airline, holds eight turbine aircraft type ratings, and has flown over 80 aircraft types. Matt is one of 25 instructors in the world to have earned the Master CFI designation for 7 consecutive two-year terms. He’s been a freelance aviation author since 2003 and owns Progressive Aviation Services, LLC (www.progaviation.com). He can be reached at: [email protected] or 414-339-4990.

Copyright 2016, Matthew McDaniel. First publication rights granted WarbirdsNews. All other rights reserved by copyright holder.

![Ghosts of Pearl Harbor: Saving the Crossroads to Marine Aviation in the Pacific Theater 24 Ewa's historic revetments proved useful during filming of the 1970 WWII-classic, Tora, Tora, Tora. [Photo Credit: Jon Voss via Abandoned & Little Known Airfields]](https://vintageaviationnews.com/wp-content/uploads/Ewa17.jpg)

![Ghosts of Pearl Harbor: Saving the Crossroads to Marine Aviation in the Pacific Theater 25 Hastily constructed revetments that protected aircraft bound for the Battle of Midway still exist today within the ruins of MCAS Ewa, O'ahu, Hawaii. [Photo Credit: via Abandoned & Little Known Airfields]](https://vintageaviationnews.com/wp-content/uploads/Ewa21.jpg)

![Ghosts of Pearl Harbor: Saving the Crossroads to Marine Aviation in the Pacific Theater 26 Hastily constructed revetments that protected aircraft bound for the Battle of Midway still exist today within the ruins of MCAS Ewa, O'ahu, Hawaii. [Photo Credit: via Abandoned & Little Known Airfields]](https://vintageaviationnews.com/wp-content/uploads/Ewa19.jpg)

![Ghosts of Pearl Harbor: Saving the Crossroads to Marine Aviation in the Pacific Theater 27 Hastily constructed revetments that protected aircraft bound for the Battle of Midway still exist today within the ruins of MCAS Ewa, O'ahu, Hawaii. [Photo Credit: via Abandoned & Little Known Airfields]](https://vintageaviationnews.com/wp-content/uploads/Ewa20.jpg)

I live in the northern Chicago suburbs. I have read that a few Douglas TBD Devastator torpedo bombers were brought to NAS Glenview in Glenview, Illinois after Midway and used as trainers and hacks. NAS Glenview was the focal point for USN carrier qualification training on the converter lake steamers USS Wolverine and USS Sable. There are about 200 naval aircraft on the bottom of lake Michigan as a result of these operations and I have to wonder if a TBD is not down there. A few years ago, a SB2U was recovered and sent to the USN Air museum at Pensacola.

Joseph,

I authored this article and live near you in the Milwaukee area. While I’m not sure how many TBD’s ended up at Glenview NAS or on the lake training carriers, it is doubtful any Midway veteran aircraft were among them. The TBD’s were decimated at Midway with only 6 of 41 returning to their carriers. It’s unlikely any of those 6 would have been sent all the way back to the Midwest. If there are any TBD’s in Lake Michigan, they are likely unsalvagable now. Most of the know, salgavable wrecks have been recovered (such as the SB2U you mentioned, now restored and on display in Pensacola and an early SDB currently being restored in Kalamazoo). For decades, Lake Michigan and its cold, deep, fresh waters were a great preservative for submerged aircraft. However, in recent years an invasive species of mussel in Lake Michigan has found the aircraft and ship wrecks to be attractive habitat and has rapidly covered most of them. Unfortunately, this has accelerated their decay, quickly making many of them unrestorable (even if salvage were a possibility). There are 4 known sunken TBD’s, two near the Marshall Islands, one near Miami, and one off the coast of Mission Beach, CA. If any exist in Lake Michigan, they’ve not yet been discovered. All TBD’s were out of USN inventory by late 1944. The last known survivor was scrapped in Nov. 1944.