When asked why folks call him C.R., the interviewee responded, “Well, try to write down Clifford Robert McCullough on most documents and there just ain’t enough space.” Born and raised into a Rockdale County share-cropping family in 1933, C.R. McCullough experienced the Great Depression and tough times. “Dad finally found steady employment at the old Roger’s Grocery Store until they closed shop,” McCullough said. “He moved to Freeman Brothers and during high school I worked in grocery stores for almost four years. I graduated from high school in 1950.” Asked which school, McCullough responded, “Which one? Shoot, there was only one, Conyers High School. Our senior class was the last one in Rockdale to graduate under the old 11-grade system.”

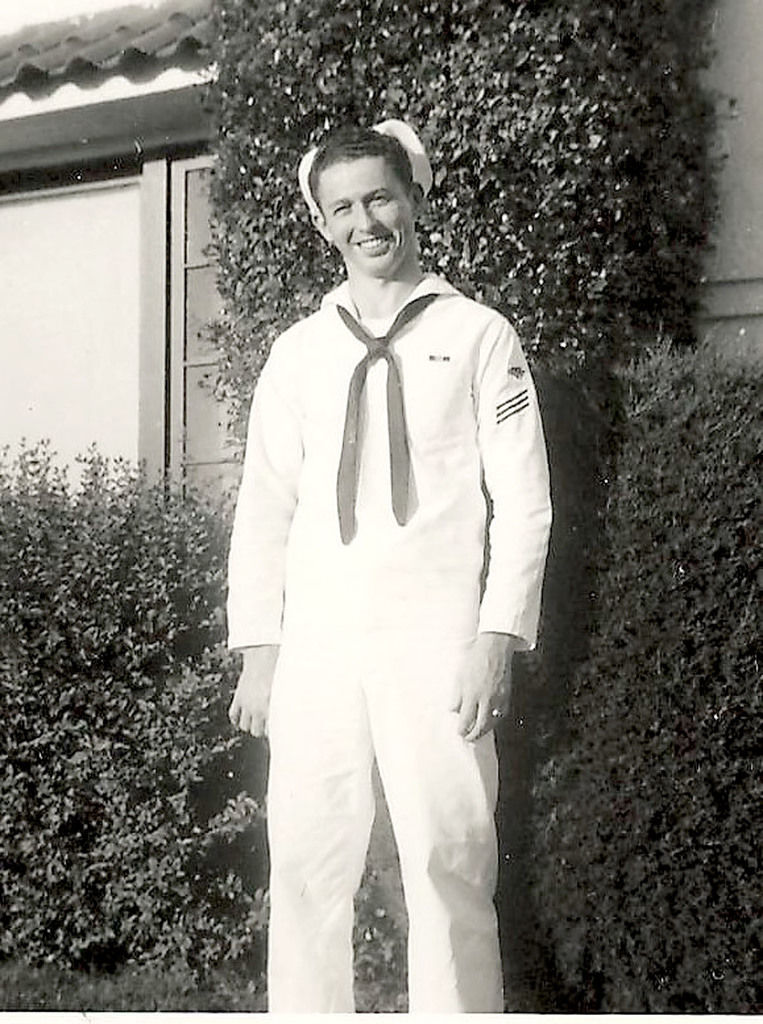

On June 25, 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea. The Korean War would last for three years. McCullough recalled, “My older brother was in the Navy pulling shore duty at Subic Bay in the Philippines when the war started. I turned 17 that July and wanted to join, but my parents refused to sign the papers. I joined on my own when I turned 18 in July of 1951.”

After enlisting in Atlanta, McCullough and a busload of other recruits traveled to Macon to board a train for San Diego. “That was a long train ride,” he said. “We spent a week aboard that train, but we did see a lot of our country. We got into San Diego around midnight. I figured we’d get a good night’s sleep then start our training in the morning. Well, at 0500 they sounded reveille. I’m standing there wondering, ‘Why in the heck did I join the Navy?’ And I kept asking myself that question after they served us beans and cornbread for breakfast.”

Laughing, McCullough said, “You know, when they threw that slop on my tray I really wondered why I’d joined the Navy. But you adapt and move on. Basic training was, well, fairly basic. We marched, went to classes; we marched some more, stacked rifles, marched to another class, jumped up and down doing calisthenics, learned ranks, and marched to another class. That lasted about 12 weeks.” During basic McCullough was instructed to list his choice of careers. “My older brother was a radioman, so that was my first choice,” he said. “Believe it or not, that’s exactly what I got.”

After passing a plethora of tests, he attended an eight-week course. “We learned Morse code,” McCullough said. “We had the earphones on all day listening to Morse code. I heard the darn code in my dreams. They didn’t teach radio repair, that’s another guy’s responsibility, so we concentrated on radio technology, finding proper frequencies, receiving messages and sending them out, and the like.” After qualifying as a radioman, McCullough was assigned shore duty. “Well, I don’t know if that was lucky or unlucky, but I spent about 18 months at the 11th Naval District in San Diego.”

Asked his duties, McCullough smiled and replied, “Making coffee. I was low man on the totem pole so I became the gofer, go for this and go for that. Wanting to do a great job, I took it upon myself to clean out the coffee pot. Shoot, I scrubbed that pot sparkling clean. Then a chief came in and got a cup. He gagged then spit out the coffee and asked what I had done. I told him I cleaned the pot. Well, he went ballistic and chewed me out, ‘Don’t you ever screw up a coffee pot in the Navy!’…. I still remember that. So I thought, well, okie-dokie, and never cleaned another coffee pot.”

McCullough ran messages, practiced Morse code, and manned a teletype. “You know, as a country boy, San Diego was a bit unusual,” he stated. “They had water shortages and still do, but dang if they didn’t paint concrete green to mimic real grass. To a boy from Georgia, that really seemed a bit weird. San Diego wasn’t much of city back then, just a typical Navy town with good and bad areas. The lower side of San Diego was a wide open area, a lot of fun, and a lot of trouble to get into.” Orders came down for the Bremerton, Wash., Naval Base. McCullough said, “They were recommissioning a WWII Essex-class aircraft carrier, the Hancock, into the first steam catapult carrier. (The USS Hancock fought in WWII, Korea, and Vietnam). When I arrived in Bremerton and saw that ship, I couldn’t believe it, the thing was monstrous. We were assigned bunks and duty stations. The communications room was right below the flight deck near the super structure.”

The USS Hancock put to sea. McCullough recalled, “We sailed down the coast to San Francisco, then sailed to San Diego to pick up our jets from North Island. The pilots trained day and night on the steam catapult. Coded messages came in from other ships, we coded and decoded, plus went up to the bridge occasionally and watched the take offs and landings.” There were advantages being in the communications room. “We also distributed the mail. If we couldn’t get fresh coffee or pastry on the nightshift, well, we withheld the cook’s mail,” McCullough said. “Needless to say, we had plenty of hot coffee, donuts, just about anything we wanted.”

On life aboard an aircraft carrier: “It’s like a small city. We had barber shops, snack bars, movies every night, a grocery store … we longed for nothing. We lost one man while I was aboard. He went to the fantail of the ship, stripped, and jumped in. They sent small boats out to save the guy, but as they approached the sailor waved, smiled, then went under, never to be seen again. The next day they discovered the ‘Dear John’ letter he had received.”

On the steam catapult: “I thought those pilots were crazy,” McCullough said. “Those guys were launched off the carrier in about 3 seconds, one heck of a ride and one heck of a jolt for the pilot. They did discover one flaw with the jets. As they revved up for launch the back of the jets would, as they said ‘sit down’ and eventually burn a hole in the wooden deck. Thus, a new metal deck was installed and they are still in use today.”

Later in 1954, McCullough got up one morning, readied for work, then tried to turn the handle on the door. “I couldn’t turn it,” he said. “I didn’t have the strength. I said, ‘to heck with it’, and went on to work, not thinking it was a big deal. Eventually I could hardly type, my hands and fingers seemed frozen. A young ensign took notice and ordered me to sick bay. Well, they ran tests and two weeks later transferred me to the hospital in San Diego. I spent four months there. Rheumatoid arthritis was setting in. I was 21 years old.”

Medically discharged as 50 percent disabled, McCullough returned to Rockdale County and walked the streets, in Rockdale and Atlanta, seeking employment. “Nobody wanted to hire me,” he said. “I finally found a job in the credit department of Warren Refrigeration Company on Memorial Drive until they closed the doors 17 years later. I worked another 19 years for a distributor for Warren until the arthritis got the best of me.” McCullough’s mobility now requires a motorized wheel chair, or as McCullough claims, his “Cadillac,” supposedly turbo charged. He and his wife, Midge, have lived in the same house for 50 years, across from a horse farm on land once used for the Bethel Grammar School.

Final thoughts on his Navy days: “It is a fact, you go in a boy and come out a man. You go in straight out of high school, you never have been on your own; you learn to obey orders, to take care of yourself. Mom ain’t there to wash your clothes, make your bed, clean for you; shoot, you have to grow up. I’m a firm believer that each kid should serve in some way after high school. It is discipline, it’s getting on a schedule and sticking to it. You screw up in the Navy and 50 guys work you over, you’re part of a team, you pull your own weight.”

On the changes he’s seen in Rockdale County: “Like the song says, they paved paradise and put up a parking lot.”

Article by Peter Macca via rockdalecitizen.com

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran. For story consideration or comments: [email protected]

To read Pete’s stories visit www.aveteransstory.us

Related Articles

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.