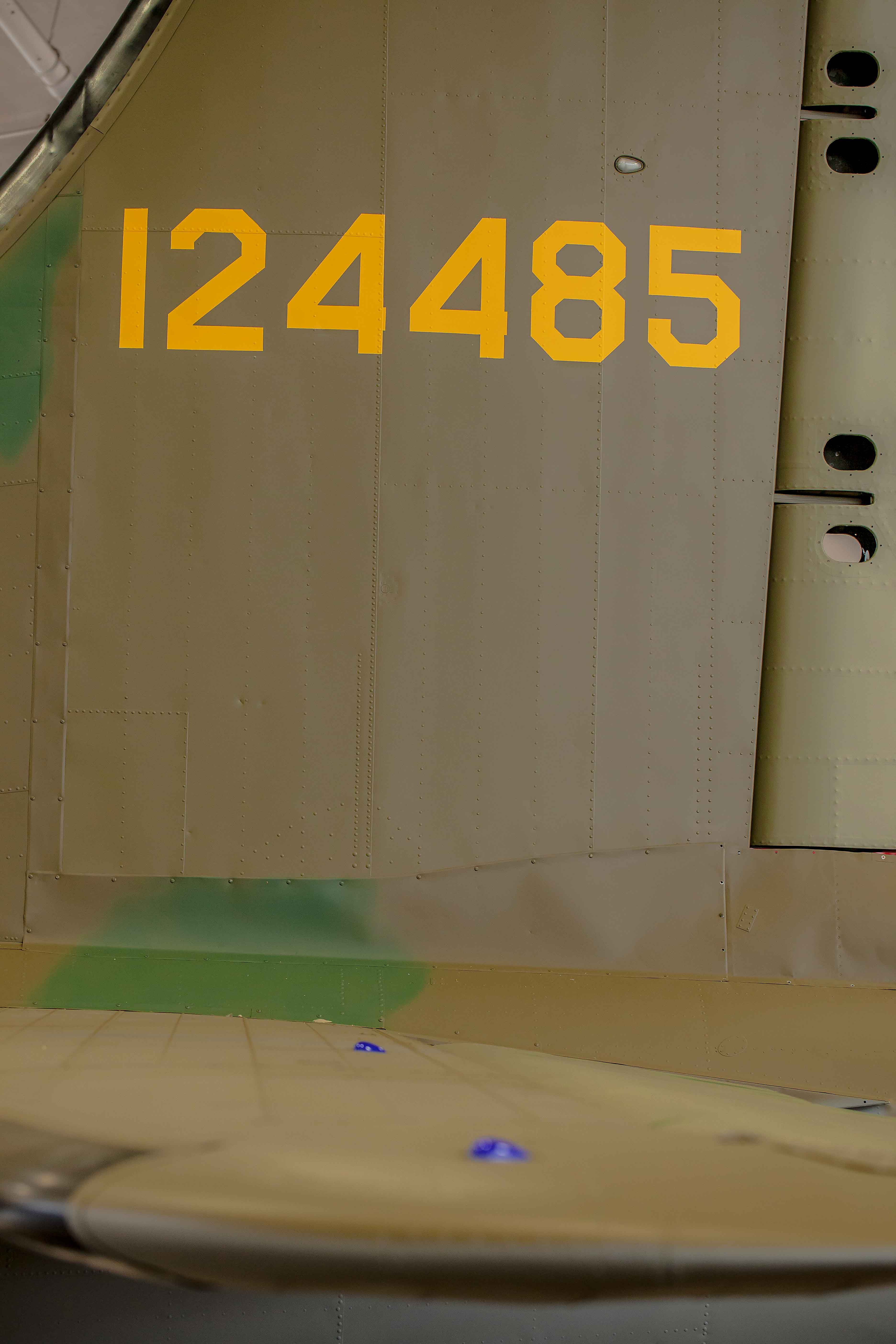

As most of our readers will be well aware, the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio is close to completing the restoration of one of their most prized exhibits, Boeing B-17F Flying Fortress 41-24485 known as Memphis Belle. Almost all of the work is done now, barring the finishing touches to the paint. The restoration itself is easily one of the most comprehensive and complex that the museum has undertaken so far, and knowing how much scrutiny the finished result will be under, they have been at pains to make it as historically accurate as practical. The museum released an article a few days ago describing some of the thought processes behind the work they have accomplished, and we thought our readers would be interested to see it, along with some beautiful images taken during the most recent work on the aircraft.

Restoration on the B-17F Memphis Belle – the first U.S. Army Air Forces heavy bomber to return to the United States after completing 25 missions over Europe – continues to move forward at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

Since the aircraft first arrived at the museum in 2005, museum staff and volunteers have worked meticulously for countless hours to preserve the iconic bomber, which was in great need of corrosion treatment, the full outfitting of an extensive list of missing equipment, and having the proper paints and techniques applied.

One of the first challenges for restoring the aircraft was to obtain a list of missing parts, determine what could be obtained from a similar aircraft, and then try to fabricate the rest.

According to Casey Simmons, a Restoration Specialist at the museum, obtaining parts for a 1940s-era aircraft was not an easy task. “For any of the parts that we needed on the airplane, if you can’t get another one from another aircraft you have to completely fabricate the part,” said Simmons. “So that means going to the blueprints, figuring out what goes into that, how they did it and trying to re-create that process.”

Some of the parts that had to be fabricated by the Restoration Division included the gun mounts; all of the flooring; new sheet metal on the right vertical stabilizer and left bomb-bay door; the wind screen and eyebrow glass in the cockpit; a fuselage longeron and rear vertical stabilizer spar.

One of the parts that Simmons helped to fabricate was the glycol heater, which went inside the left wing of the aircraft and provided heat for the cabin. “No one will ever see it but we had to completely fabricate that from scratch and it is fully functional,” said Simmons. “But I know the work that went into it, and I know where it’s at, so it’s pretty neat.”

Among the most challenging aspects of the restoration of the Memphis Belle was painting the aircraft. The painting process lasted several months with plans calling for the aircraft to look as it did after completing its 25th mission, but before it went on the war bond tour. Authentic paint for the time period was used so that the aircraft would look as close as possible to that period in time. “We were looking at pictures down to the single rivets on the aircraft to try to get markings where they belong,” said Simmons. “You have a lot of different images from different sources, and you’re trying to match colors, but the color in every photograph is just a little different depending on how the film was developed. So the hardest part is getting it exactly the way it needs to be.”

Even in going to those lengths, the color on the vertical tail and control surfaces are slightly different shades of green than the rest of the aircraft and Simmons has an explanation for that too. “When the aircraft first came out of the factory, it would have been pretty much one color of green,” said Simmons. “However, as you can see in the photographs from that time period after it completed its 25th mission, the paint began to fade and so we had to replicate that as well.”

Museum Curator Jeff Duford, who led efforts to research the colors and markings on the Memphis Belle, discovered that although the paint on the tail faded over time, the paint that’s on the fabric-covered control surfaces faded faster and to a greater degree than the rest of the aircraft. So the museum team worked until they got those colors right as well. “We actually mixed 25 different samples to get to the right shade of green to ensure that the color is accurate,” said Duford.

To a large extent, Duford credits the 1944 William Wyler film, “The Memphis Belle,” as the reason why so much information about the aircraft was available. Wyler volunteered to serve the country and the Army Air Forces gave him a commission as a Major and sent him over to England to film heavy bomber operations. He brought a camera crew with him and they shot hours and hours of color footage of heavy bomber operations including some scenes in combat. “In the film you see aircraft dropping bombs, aircraft getting shot down, German fighters attacking them, and real flak” said Duford. “So Wyler and his cameramen were taking the very same risks that the bombing crewmen were, and in fact one of them was killed in a combat mission.”

Wyler’s team shot more than 11 hours of color footage, which is now preserved in the national archives and the museum obtained a copy of it. “Because of this color footage, we’re able to correctly mark and configure the aircraft today,” said Duford. “It is truly astounding because we’ve worked on many restorations here and by far there is more evidence about the Memphis Belle because of these out-takes than any other restoration that we’ve done.”

In addition the museum also obtained copies of more than 5,000 original documents related to the combat history of the Memphis Belle and heavy bomber operations, which provided a wealth of information including details on each crewmember and mission.

According to Duford, all of the time and effort spent on all of the details to accurately restore the aircraft – from its structural parts to the paint that’s used to color its appearance – is what this national treasure deserves.

“We have symbols in the history of our country – things like the flag that flew at Iwo Jima; the battleship Arizona – these recognizable symbols of the American experience, and the Memphis Belle is truly one of those icons in our history,” said Duford. “And now fittingly so, the aircraft will be preserved at the Air Force’s national museum for generations to come.”

Although restoring the Memphis Belle has been a long and strenuous process – which will continue in the interior of the aircraft even after it has been placed on display – it’s also been very rewarding as well, said Simmons. “When I first got here in 2007, the aircraft was in multiple pieces – just individual bare metal sections of the aircraft,” said Simmons. “Now it is a complete aircraft that actually looks like something, and it’s just the biggest transformation that you could ever imagine.”

Plans call for the B-17F Memphis Belle exhibit to open to the public on Thursday, May 17, 2018, with celebratory events May 17-19, 2018. This three day event will include a WWII-era aircraft static displays, flyovers, WWII reenactors and vehicles, memorabilia and artifact displays, music from the era, related guest speakers for lectures, book signings and films, including both Memphis Belle films in the Air Force Museum Theatre.

The National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, located at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio, is the world’s largest military aviation museum. With free admission and parking, the museum features more than 360 aerospace vehicles and missiles and thousands of artifacts amid more than 19 acres of indoor exhibit space. Each year about one million visitors from around the world come to the museum. For more information, visit www.nationalmuseum.af.mil.

I believe i have a set of crew thermos for a flying fortress in original leather case.