At one of the premier aviation museums on the US East Coast, the Cradle of Aviation Museum (COAM) of Garden City, NY, is nearing the finish line of their project to build a replica of a Fokker D.VII, one of the most capable fighter aircraft of the First World War. Designed by German designer Reinhold Platz, working for Anthony Fokker, a Dutch national who established his business in Germany, the D.VII was the culmination of the fighter designs of the Fokker Flugzeugwerke based in Schwerin, and many WWI aviation historians have touted it to be the best fighter to see combat with the German Luftstreitkräfte (Air Service). This point is underscored not only by its combat performance but by the fact that it was the only aircraft to be mentioned in particular among the aircraft ordered for immediate surrender following Germany’s signature on the Armistice that ended the First World War.

By the end of 1918, the Fokker D.VII would also serve the victors of the conflict as part of the war reparations Germany was forced to pay after the Armistice and the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles. The United States Army Air Service and Marine Corps would bring a combined total of 142 D.VIIs back to the United States, and not only flew them in flight evaluations tests at airfields such as McCook Field in Dayton, OH, but would even deploy them in operational units both in the United States and in the occupied Rhineland.

In addition to being flown in American aero squadrons, Fokker D.VIIs in U.S. service, the design was also fitted with several American engines, from the Liberty L-6 (which bore a striking resemblance to the original Mercedes D.III and BMW D.III 6-cylinder inline engines) to license-built Hispano-Suiza V8s and even Packard Liberty L-12 engines. After they were retired from military service, many D.VIIs would be used in Hollywood war movies of the 1920s and 1930s, such as Hell’s Angels, and elements of their design features would profoundly influence subsequent U.S. biplane fighter designs of the 1920s and early 1930s. Today, however, only eight genuine Fokker D.VIIs are known to exist in museums around the world, but numerous flying and static replicas and reproductions, both full-scale and scaled down, are present in more museums and private collections. For the COAM, though, the construction of a Fokker D.VII for their institution also reflects the local history of Garden City.

Much of the museum itself is housed in hangars leftover from Mitchel Air Force Base, a military airfield established in 1917 as Mitchel Field during WWI and was used until its closure in 1961, which adjacent to other local airfields such as Roosevelt Field that have long been redeveloped into commercial and residential purposes. In 1919, Mitchel Field became the home of the 1st Aero Squadron (now the 1st Reconnaissance Squadron), which had seen combat in France during WWI and participated in the subsequent occupation of the Rhineland. The squadron had flown German-built types such as the Fokker D.VIIs and brought some of these back with them to Mitchel Field, where the same fighters that had battled American pilots over Flanders’ fields were now flown by American pilots above the skyscrapers of Manhattan. Given its significance to aviation history, it only made sense for the Cradle of Aviation Museum to have at least a full-scale replica of a Fokker D.VII, and luckily for the museum, they would not have to look far for one.

During the late 1970s, a pilot and farmer named John Talmage from Riverhead, NY, about an hour east of the museum in Garden City, began work on building a replica of a Fokker D.VII for himself to fly, complete with a rare Liberty L-6 inline engine built in WWI by the Hall-Scott Motor Car Company of Berkeley, CA. Talmage was a man of many interests besides flying, from preserving farmland in his county from suburbanization, to building both a sailboat and a hovercraft. However, although he built 90% of the aircraft’s internal structure and acquired several key components for the D.VII replica, it seemed time had a habit of slipping away from him on the Fokker, and year after year passed without him completing it. Finally, Talmage decided to put the project up for sale, and in 2014 he donated it to the Cradle of Aviation Museum, where it entered the museum’s restoration workshop for completion to static display.

There were many parts of the Fokker that required the museum to search their archives for documentation on the assembly of the 100-year-old design, and to task some of its volunteers, such as retired Pan Am aircraft mechanic Paul Steidel, with fabricating new parts from scratch. The COAM also established contact with a veritable institution to fans of vintage aircraft, the Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome of Red Hook, NY. The ORA has long flown a faithful reproduction of a Fokker D.VII, complete with an original Mercedes D.III, and officials at Old Rhinebeck, such as the late Brian Coughlin, generously provided exclusive access to the D.VII for reference.

Since then, restoration volunteers have been hard at work finishing the D.VII for display. The current focus of the restoration has been the wood and fabric wings of the Fokker D.VII. The lower span is made up of two wings attached through joints to the fuselage of the aircraft, while the upper wing is a single piece when fully assembled, though it consists of 28 ribs that have to be stitched together with the fabric with a foot-long needle. Another key feature of the wing design was the internal bracing in the wing that eliminated the need for external bracing wires between the wings as seen on many biplanes both during and after WWI. At this point, restoration volunteers Tony Pedalino, Phil Jaeger, Russell Rhine, Joe Kirby, David Fitzpatrick, Lester Orlick, and Jeffrey Wright stitched fabric to the ribs of the Fokker’s wings. In this, restoration specialist Peter Truesdell used his experience working with sailboats to help instruct the volunteers in fabric work. With this complete, the two sets of wings will be doped and painted.

Moving to the fuselage, it was different from most other fighters of the Great War in that while the fuselage was covered with doped fabric, the internal structure was made up of a welded tubular steel framework, which would, like other features of the design, have a wider impact on subsequent interwar fighters. Much of the framework had been built by Talmage over the course of his time building the replica, but the engine cowling had to be fabricated at the museum’s workshop.

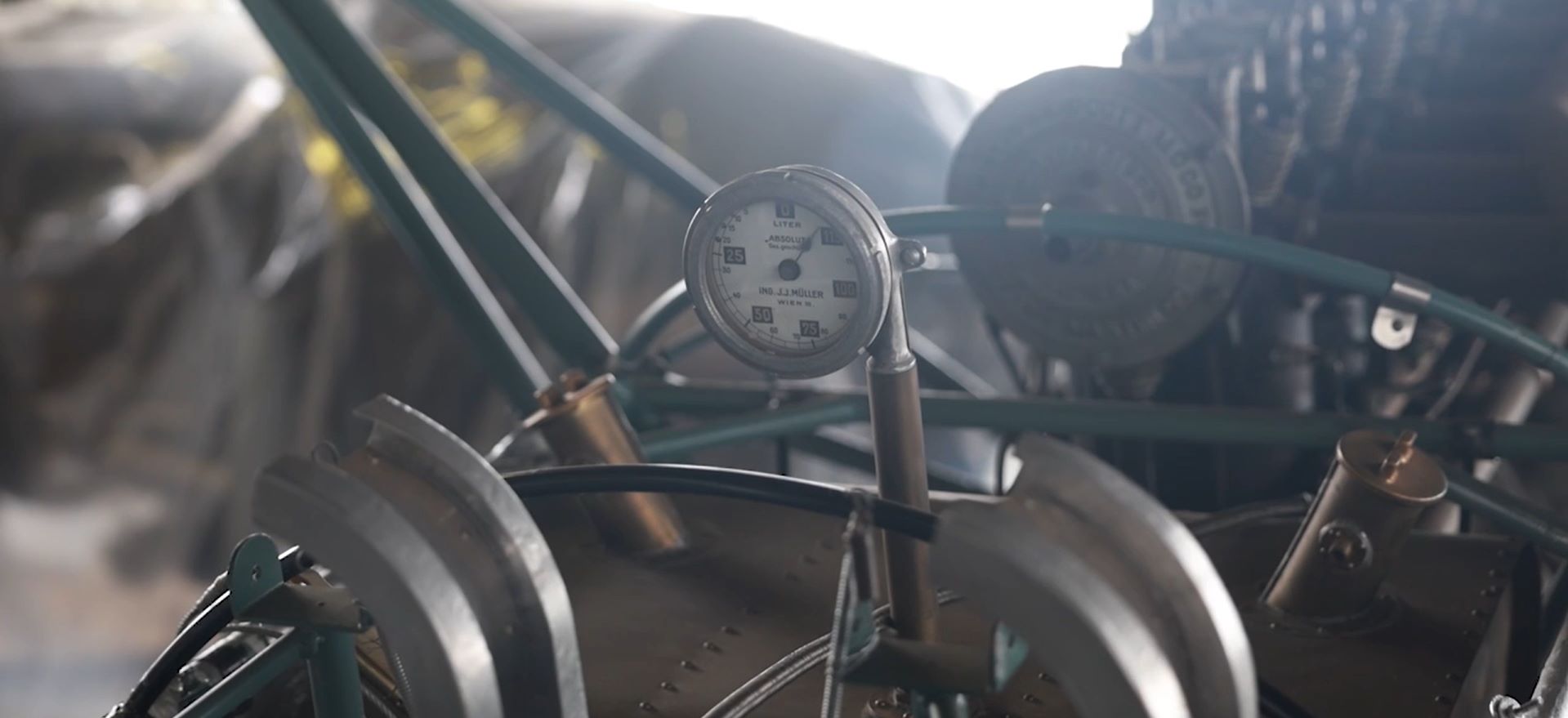

While the COAM’s Fokker D.VII may be a replica, there has been a great emphasis on finding as many original parts to incorporate into the build as possible. Truesdell and museum historian Joshua Stoff have tracked down gauges and researched authentic markings for the instrument panels, sparse even by WWII standards some 20 years later. They even found an old anemometer, similar to those mounted on the Fokker’s N-struts at the wingtips to indicate the plane’s airspeed. Finding tires of the right width was also a challenge, with the closest thing to the real deal being a pair of Ford Model A replica tires that had to be shaved to match the dimensions seen on the wheels of original D.VIIs.

According to the museum, the timeline for the completion of the project is still fluid, but they hope to have the D.VII ready for an upcoming exhibition at some point. However, like many of our readers, we will be eagerly anticipating the day when the Fokker D.VII goes on display at the Cradle of Aviation Museum. For more information, visit Cradle of Aviation Museum, Garden City, Long Island, NY.

Luftstreftkrafte means Imperial German Air Service, not Combat Air Forces. Please, recheck.your research before you write anything else.

It just means Air Force actually. Please, recheck your research before you write anything else.