By Adam Estes

The Museum of Flight (MOF) in Seattle, WA is known for having one of the most extensive collections for an aerospace museum on the US West Coast, with a collection of aircraft spanning the history of flight, from replicas of Leonardo da Vinci’s glider designs to space capsules. But the MOF also displays a number of original and reproduction military aircraft of World War I and World War II in its J. Elroy McCaw Personal Courage Wing, with the second floor dedicated to the aircraft of WWI. It is from this floor that two German aircraft have recently been pulled from display and are now undergoing refurbishment at the MOF’s Restoration Center at Paine Field in Everett, just north of Seattle. These are the museum’s original Pfalz D.XII and a full-scale reproduction of a Fokker D.VII, which represent two of the most advanced German fighters of the First World War and each has a fascinating story to tell.

The Pfalz D.XII was one of the last frontline fighters employed by the Imperial German Air Service in World War I. Manufactured by Pfalz-Flugzeugwerke GmbH (Palatinate Aircraft Works) based in Speyer, the D.XII served as a contemporary of the Fokker D.VII and a successor to Pfalz’s most recognizable fighter design, the Pfalz D.III. The aircraft was powered by a Mercedes D.III six-cylinder inline engine and equipped with the standard armament of most German fighters; two LMG 08/15 “Spandau” machine guns (a variation of the Maschinengewehr 08 (MG 08) that was developed for aerial combat, and were often nicknamed for the Spandau Arsenal in Berlin that developed these guns).

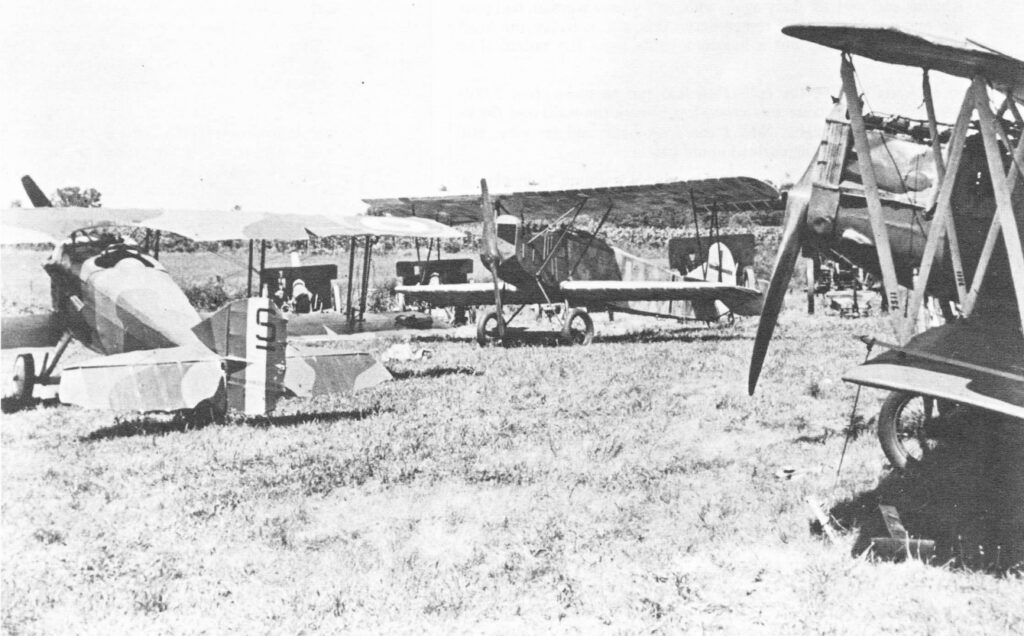

The Pfalz D.XII was first flown in March 1918 and entered operational service the following June, where it would be primarily deployed among Bavarian aviation units. While pilots praised its improved performance over the Albatros D.Va and the Pfalz D.III, they far preferred the Fokker D.VII over the D.XII as the D.XII had a longer takeoff roll, was heavy on the controls and less maneuverable than the Fokker, and a weak landing gear combined with a tendency to float above the ground meant that it required added caution on landing. Mechanics also preferred the D.VII due to the cantilever wings that required none of the bracing wires present on the D.XII, which also required an extra pair of struts for its wings. Plus, the fabric covering over the Fokker’s tubular fuselage framework ensured that it was easier to repair than the wooden shell of the Pfalz.

By the end of the war, only around 750 to 800 Pfalz D.XIIs were built, compared to about 3,300 Fokker D.VIIs being produced, with the latter even seeing limited production after the war. Today, only four Pfalz D.XIIs remain in the world, with examples on display in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, the Musée de l’air et de l’espace at Paris-Le Bourget Airport, France, and two in the United States as part of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., and the MOF respectively.

Like all surviving Pfalz D.XIIs, little to nothing is known about the wartime history of the MOF’s Pfalz D.XII, but it was one of many German aircraft brought to the United States for evaluation purposes, and as part of Germany’s war reparations. It is highly probable that the museum’s Pfalz was initially processed through the headquarters of the American occupational forces in Germany at Koblenz, which was a collections center for German aircraft to be surrendered in accordance with the terms of the November Armistice. From there, the aircraft was likely processed at another American facility in France before its shipment to the United States around 1919. The next definitive account of the MOF’s Pfalz and of another surviving example does not come until after the two aircraft were auctioned off by the US Army Air Service.

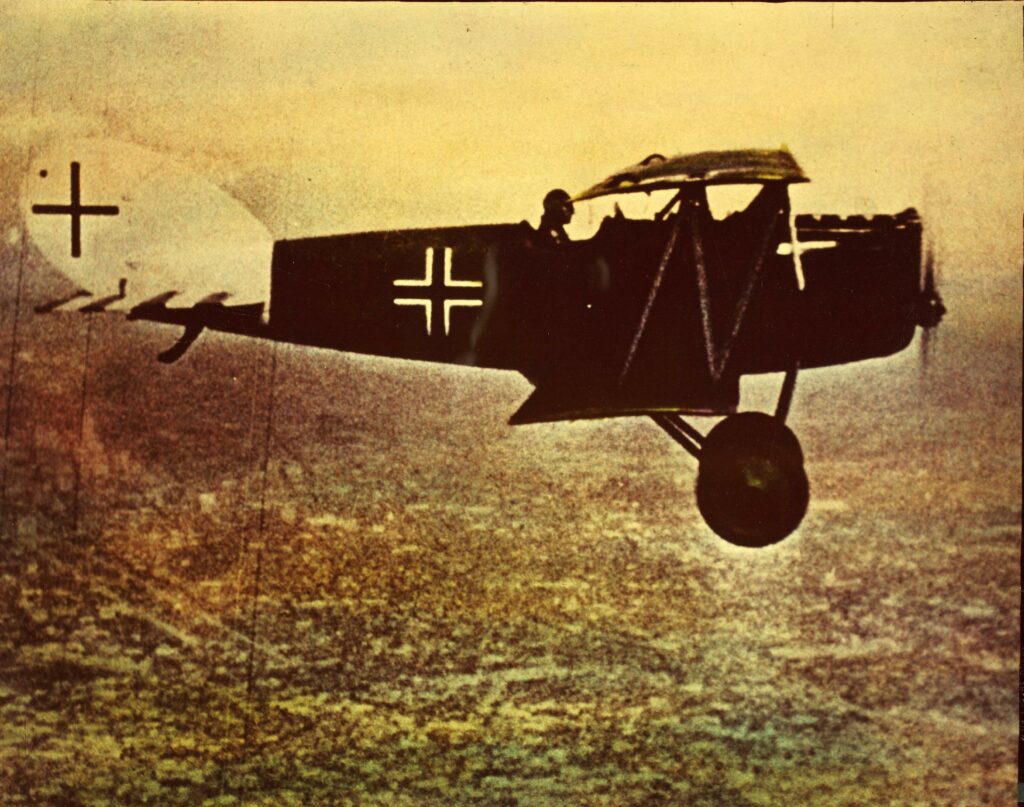

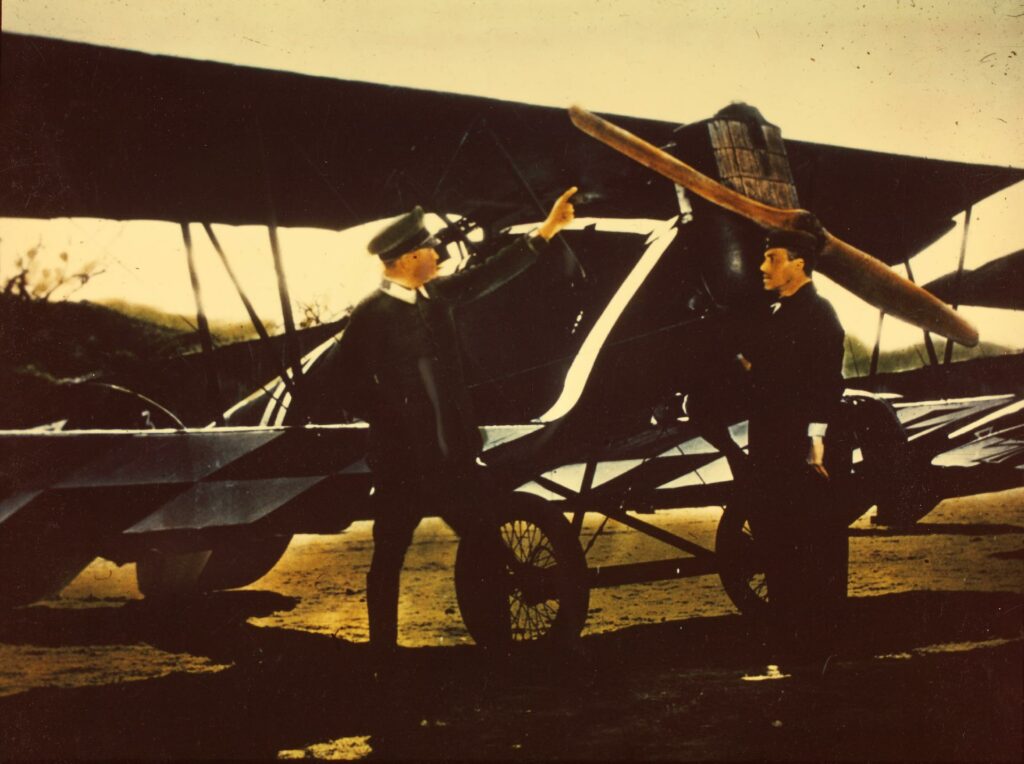

According to the late aviation historian Peter M. Bowers in an article for Flight Journal titled “Tracking the Pfalz”, two D.XIIs were bought by the Crawford Airplane and Supply Co. in Venice, CA sight unseen, packed in shipping crates and labeled only as “180hp German pursuit planes”. The Crawford Co. expected to receive two Fokker D.VIIs that could be converted into two seaters. Instead, they received the deteriorated wooden fuselages of the Pfalz fighters, which would not be commercially viable for conversion into two seaters. Nevertheless, the two D.XIIs were leased to the producers of the 1930 film The Dawn Patrol, where they were painted in spurious German colors and used to fill out the flightline of the German airfield in the movie.

In 1936, both aircraft in Crawford’s Venice lot attracted the attention of a young collector named George Burling (G.B.) Jarrett, an Army reserve officer who had amassed a collection of WWI equipment, consisting of items as far ranging as uniforms, small arms, machine guns, artillery guns and shells, many of which were shipped to North America from Europe by Jarrett, and who forayed into collecting WWI airplanes, including a Thomas-Morse Scout, Sopwith Camel, Nieuport 28, Fokker D.VII, and a SPAD VII among others. Jarrett displayed his collection both on the Steel Pier in Atlantic City, NJ, and on a farm near Moorestown in that state. Having already acquired his SPAD and Fokker during prior trips to Los Angeles, Jarrett returned there in 1936 to find more aircraft too worn out for further use in the film industry, discovering the two Pfalz fighters and a second SPAD VII. One of the two Pfalzes was acquired by Paramount Pictures property manager/electrician Louis C. “Buck” Kennell, who was also a private pilot, and would later be donated by Kennell to the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in 1951, while Jarrett acquired the other and what was to be his second SPAD VII.

Jarrett wrote later in an article for the American Aviation Historical Society: “The other SPAD and Pfalz were shipped to Moorestown, costing about $600…. The Pfalz had been used in the film, Dawn Patrol, with checkerboard paint scheme, a typical movie treatment with water colors. For about a day I scrubbed the surfaces and nearly all the [water paint] came off. After the broken woodwork was repaired it was then refinished in the brown paint scheme as it had had when it left the Pfalz factory in 1918. There were only two pieces of the original German camouflage fabric, these on the horizontal stabilizer.

“The upper wing […] was of one-piece construction, but to get it home from San Pedro, it had to go in one package. I asked Joe Aiken to saw it in two, to go in the package aboard ship. Though it made me shudder, I asked him not to think about it but to saw it, inside the center section fittings. Saw away he did, and later I was able to repair it enough for display. From the aircraftsman’s angle the repair would not have passed the inspector’s eye, but it stayed together and we could move it about the field for display. It was complete, with a pair of lovely Spandau guns on the fuselage.”

During WWII, Jarrett was called away from his collection to serve in active duty as one of the US Army’s premier ordinance specialists, being shipped to North Africa to supervise the shipment of captured armaments back to the United States and assist British soldiers in the use of American arms provided through the Lend-Lease Program. After the war, Jarrett remained with the Army, but found that his aircraft at Moorestown had deteriorated in lieu of his absence, and were in desperate need of restoration. While he found several individuals who were interested in some of his aircraft, the Pfalz D.XII would be among four airplanes Jarrett would sell for a total of $500 to a young collector named Frank Tallman, who had served stateside as a naval aviator during WWII.

Tallman would acquire the Pfalz, a SPAD VII, a Nieuport 28 and a Sopwith Camel from Jarrett, but he would delegate the task of restoring the vintage planes to others. For the Nieuport and the Camel, it was Ned “Ken” Kensinger, a charter member of Experimental Aircraft Association’s Chapter 2 in Peoria, IL but while pondering over who would take on the Pfalz and the SPAD, Tallman received a phone call from an aircraft restorer from Georgia named Robert Rust. Rust would restore the aircraft from 1955 to 1958, and Frank Tallman made the Pfalz’s first post restoration flight on January 3, 1959 at Fulton County Airport, near Atlanta, GA with the aircraft being registered with the newly-formed FAA as N43C.

By 1961, Frank Tallman had relocated to Flabob Airport in Riverside, CA where he also flew the Camel and the Nieuport he bought from Jarrett. That same year, Tallman established a partnership with veteran movie and air racing pilot Paul Mantz to form Tallmantz Aviation at Orange County Airport (now John Wayne Airport) in Santa Ana, California, merging their two collections of vintage aircraft. While many of the other Tallmantz found work in Hollywood productions, the Pfalz never got a chance to star in another WWI blockbuster. However, Tallman would fly the aircraft at numerous airshows through the 1960s or have it displayed at Tallmantz’s museum, Movieland of the Air.

1965 would bring two major blows to Tallmantz Aviation, with Tallman receiving a severe leg injury from a go-kart accident that resulted in the subsequent amputation of his left leg above the knee, and Paul Mantz being killed in a crash during the production of the film Flight of the Phoenix. This double blow led directly to Tallman being faced with little alternative but to sell around 40 airplanes (including the D.XII) to the Rosen-Novak Auto Company of Omaha, NE for them to officiate an auction. On May 28, 1968 the auction was held at Movieland of the Air, and the winning bid of $16,000 for the Pfalz D.XII went to the Aeroflex Museum of Aeroflex-Andover Airport near Newton, NJ. This museum, seldom remembered today, also acquired several other Tallmantz aircraft at auction before they would find a new owner in the form of Korean War fighter ace Dolph Overton, who in December 1968 established the Wings and Wheels Museum in Santee, SC.

Throughout the 1970s, the Pfalz D.XII would be displayed alongside numerous other aircraft and automobiles in a hangar just off Santee’s grass airstrip. By the late 1970s, though, Santee was not attracting the number of visitors needed to sustain operations at the museum, so Overton took the Wings and Wheels’ collection to Orlando, FL, setting new roots near the airport. But even this would not save the museum, which closed its doors for the final time in 1981, with its collections being auctioned off by Christie’s auction house on December 6 of that same year. In this second museum auction for the Pfalz it was acquired by Doug Champlin, who was busy creating the Champlin Fighter Museum (CFM) in Mesa, AZ and the aircraft headed westward once more.

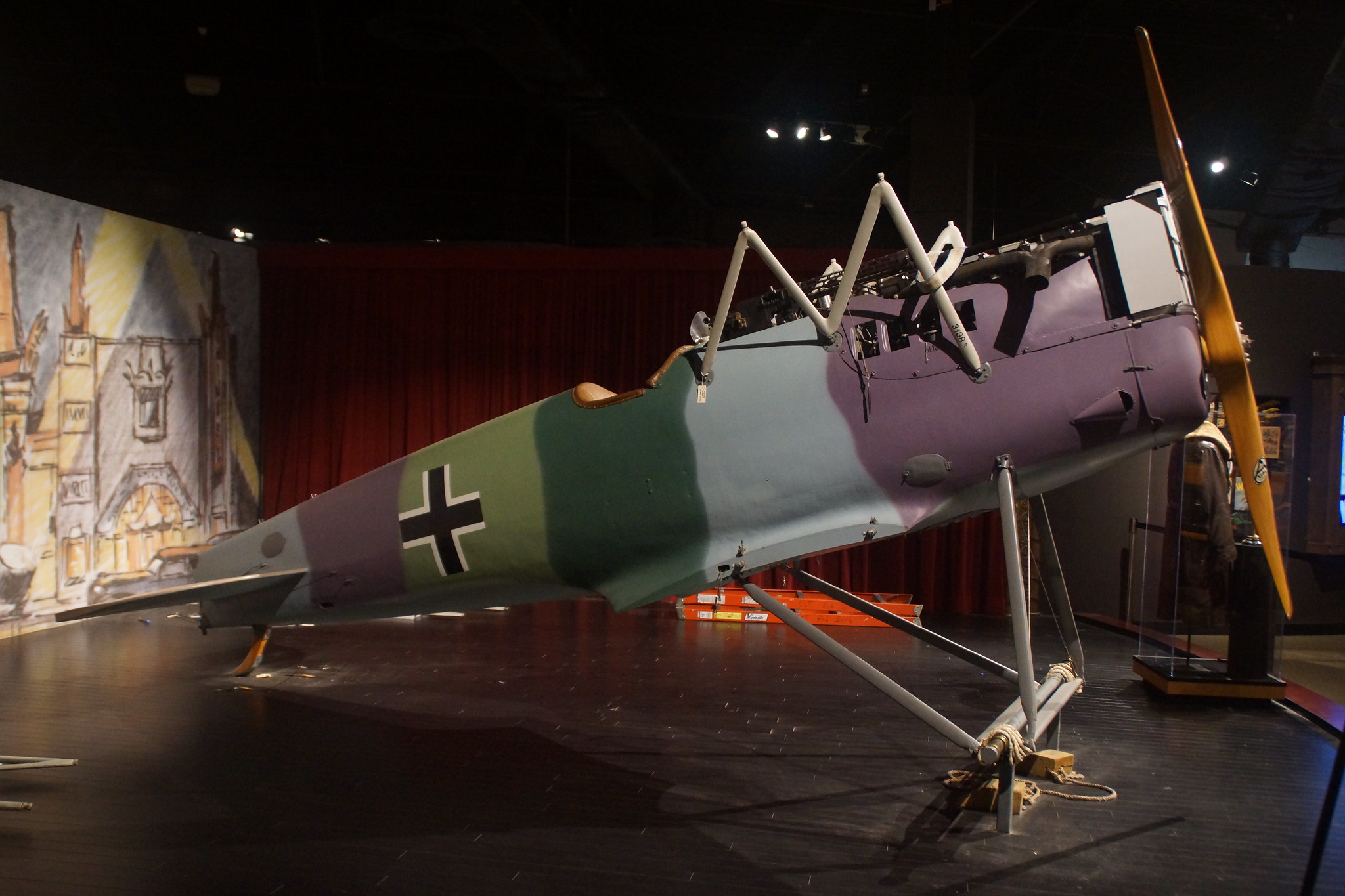

When he received the aircraft, though, Champlin felt it would be necessary for the aircraft to undergo a second restoration with emphasis on the cockpit and the fabric surfaces. This would be conducted by GossHawk Unlimited at Casa Grande, AZ with supervision for antique aircraft restorer couple Jim and Zona Appleby of California, who had previous connections with Tallman. Upon completion of this project, the Pfalz D.XII sat proudly on display until the CFM itself closed on May 26, 2003, after which it and the majority of his collection of WWI and WWII aircraft moved to the Museum of Flight in Seattle.

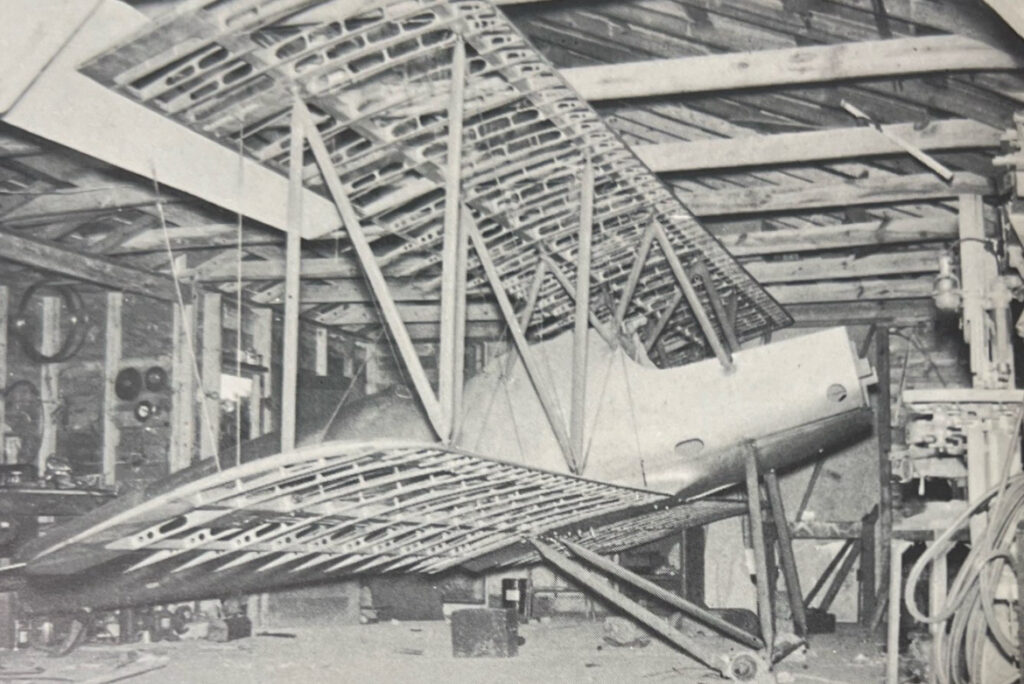

Another of these aircraft was a Fokker D.VII reproduction, the second German WWI aircraft currently under restoration up in Everett. This machine’s fuselage framework was built for Doug Champlin by WWI aircraft builder Joe DiFiore in the 1980s before the Applebys took over the project, building the wings and tail surfaces, and installing an original Mercedes D.III engine and two original Spandau machine guns. At both the CFM and the MOF, the aircraft has been displayed in the markings of German ace Rudolf Berthold, whose aircraft were easily distinguished by his personal emblem of a winged sword.

Having been displayed in the MOF’s Personal Courage Wing for 20 years since the closure of the CFM, the Pfalz D.XII and the Fokker D.VII have been removed from the Personal Courage Wing for refurbishment at the museum’s Restoration Center at Paine Field. Once complete, the two aircraft will return to the museum in downtown Seattle and rejoin the other original and reproduction WWI aircraft that remain on display.

During this process, the museum has made several connections regarding the Pfalz D.XII. While there is still much to be learned about the aircraft, museum officials have been making important contacts to help them ensure the historical accuracy of the D.XII’s restoration. In the Curator’s Corner profile of the July/August 2023 issue of Aloft Magazine, the museum’s official magazine, Matthew Burchette made the following statement regarding the Pfalz: “So far, the work has centered around replacing the camouflage fabric on the wings and tail with linen printed to look just like the original. As we continued to work, our need for more assistance became apparent. We needed an expert in World War I aircraft. I wish I could say I ‘knew a guy’ in this case, but I didn’t. But I made a few cold calls that paid off in a big way. I found Fred Murrin, who had worked with Sir Peter Jackson’s World War I collection for nearly a decade. Fred brought with him John Weatherseed, a World War I expert from Canada.

“It was quickly apparent that both men had a depth of knowledge-and a contact list-that would be extremely helpful. As they helped us with the wings, my attention soon turned to the fuselage. The Pfalz D.XII has a camouflaged wooden fuselage painted in green, gray, and brown bands. I had a suspicion that our aircraft’s colors were inaccurate. Only four D.XIIs are left, so certain information can be sparse. However, a call to John led to an exciting connection. He knew the head of the restoration team at the Australian War Memorial, who worked on their Pfalz. They uncovered untouched paint during their work and made precise paint chips. Through my contact with John, he had the chips sent to us. A single contact connected us to a web of people, helping us clear a major hurdle in making our Pfalz D.XII one of the most accurate in the world. It’s WHO you know, indeed.”

As for the Fokker D.VII reproduction, the MOF is also set to repaint that aircraft in a new scheme. Matthew Burchette has stated that the reproduction was patterned off a D.VII constructed in the Ostdeutsche Albatros Werke (East German Albatros Works; OAW) in Schneidemühl (today a part of northwestern Poland and known by its Polish name Piła). However, Rudolf Berthold’s original D.VII was manufactured in the Fokker factories rather than the Albatros factory. Burchette has stated that when the D.VII emerges from its restoration, it will wear a new scheme — yet to be publicly announced — representing a wartime OAW D.VII.

We will keep or readers up to date on the latest developments from the Museum of Flight as they become publicly available, and look forward to seeing the final result of the work on both the original Pfalz D.XII and the Fokker D.VII. Special thanks to Matthew Burchette of the MOF for his assistance in the production of this article.