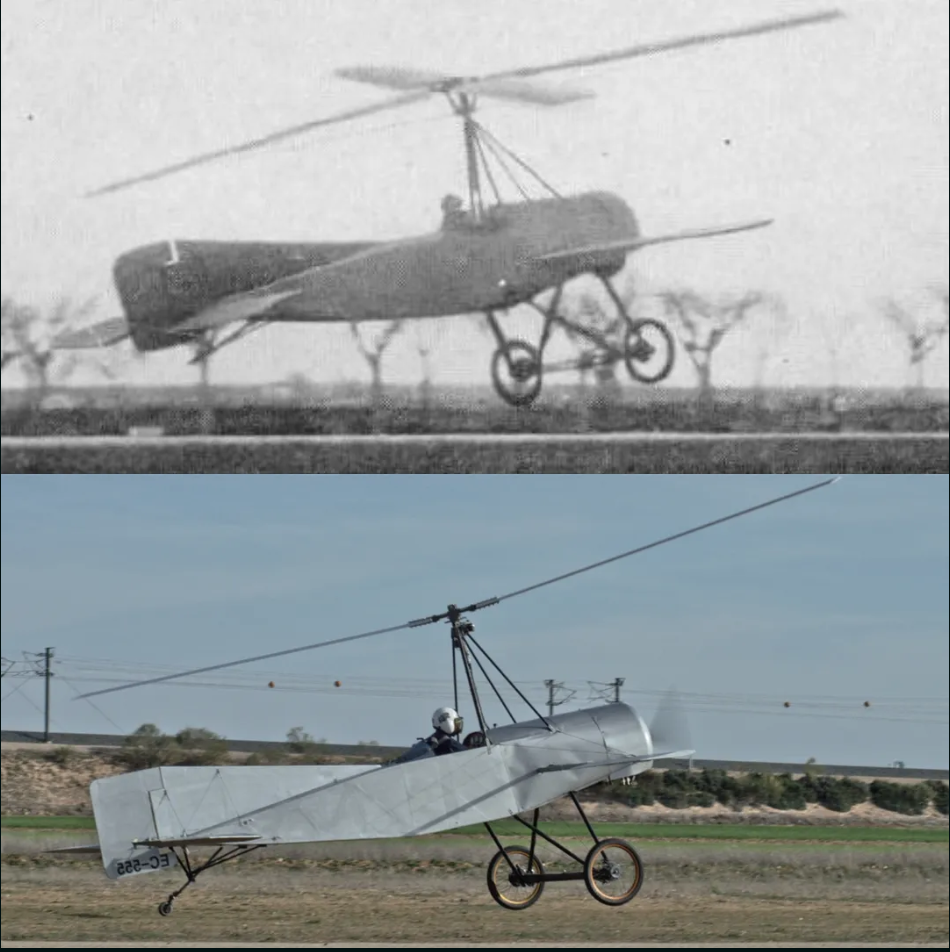

The replica of the historic Cierva C.4 autogyro is flying again. After a mishap during a previous flight, which resulted in damage to the aircraft, the passionate team behind the Centenario del Autogiro association rebuilt the autogyro. Unfortunately, during preparations to present the aircraft at Airbus’ CASA centennial, a combination of factors—crosswinds, rotor control issues, and a tail skid—led to an accident, damaging the autogyro.

However, the dedicated team didn’t let this setback end their journey. They’ve rebuilt the C.4, upgrading its engine to 100 horsepower, and as of September 10th, the autogyro is back in the skies, launching from Camarenilla Airfield in Toledo. Now equipped with a more powerful 100-horsepower engine (up from 80), the C.4 took to the skies once again on September 10, 2024, from Camarenilla Airfield in Toledo.

The project began as an initiative by a group of friends from the Getafe Ultralight Club to honor the 100th anniversary of Juan de la Cierva’s pioneering flight in his C.4 autogyro in January 1923. After over a thousand hours of design and construction, the replica C.4 was unveiled at Getafe Air Base in January, near the site of the original flight. Publicly presented in March at Camarenilla, the team later transported it to Ocaña Aerodrome for its first test flights, where ground trials and a brief lift-off occurred.

The Original C.4 in History

by James Kightly

Like many aviation pioneers, Spaniard Juan de la Cierva sought a way of developing a ‘safe’ aircraft and decided to attempt this by developing a rotorcraft, which would retain the wings’ airspeed irrespective of the aircraft’s forward speed. His first three designs were unsuccessful, due to issues with managing the (unpowered) rotor, but his fourth – the C.4 – achieved the first recorded flight of a powered, self-lifting autogyro in January 1923. It was flown by Alejandro Gomez Spencer at Cuatro Vientos airfield in Madrid, Spain.

The specific breakthrough was fitting the rotor with ‘flapping’ hinges, enabling each rotor blade to move up and down, compensating for the difference of lift and airspeed with advancing and retreating blades in forward flight. When the C.4’s engine failed shortly after an early test flight takeoff, the pilot brought the aircraft to a safe autorotating landing, proving one element of the type’s safety concept.

Cierva, alongside colleagues he collaborated with frequently, achieved many more developmental steps, and these advances fed into the later success of the helicopter, which used many of Cierva’s breakthrough ideas in rotor design. A helicopter, of course, uses a powered rotor arrangement, which is the vehicle’s fundamental difference from the gyroplane, which features a free-wheeling rotor. As a consequence, helicopters typically offer significantly greater performance, but gyroplanes are far less complex and expensive to manufacture or maintain.

Tragically, and somewhat ironically, Juan de la Cierva y Codorníu, 1st Count of la Cierva, died as a passenger in a fixed-wing aircraft when the KLM Douglas DC-2 he was aboard crashed soon after take-off from Croydon Air Port near London, England on a foggy morning, December 9th, 1936.

Report and photographs with many thanks to José Manuel Gil, Aerospace Engineer, light aircraft pilot, blogger, and podcaster at https://blog.sandglasspatrol.com. Please follow José’s blog for more details in Spanish.

*The type is known as an autogyro or gyroplane. Juan de la Cierva named it the ‘autogiro’ originally, later patenting that spelling, which is thus correct only for use with Cierva (and derived) examples.