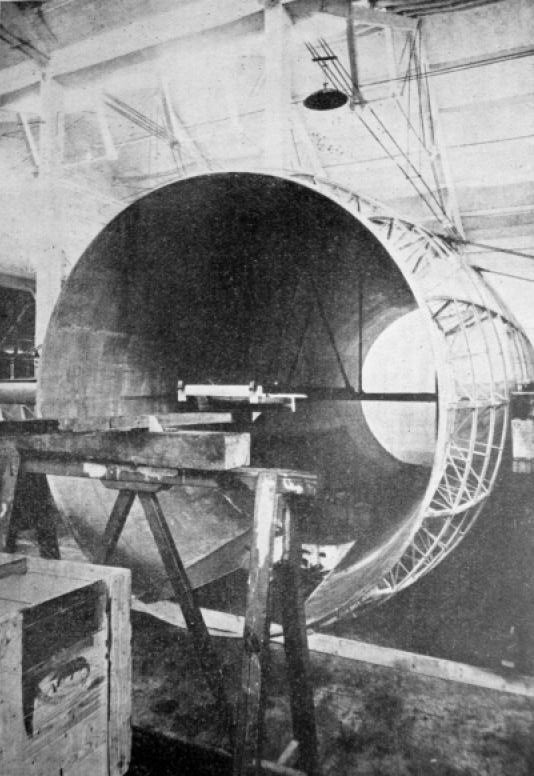

Ninety-three years ago today, on October 7, 1932, the Stipa-Caproni made its first flight. This experimental aircraft was designed by Italian aviation pioneer Luigi Stipa and built by the Caproni aircraft company. Its design was highly unconventional: the fuselage encircled the engine and propeller, essentially forming a barrel-shaped airframe that operated like a ducted fan. Stipa’s goal was to incorporate an “intubated propeller,” or venturi tube, into the design. Using Bernoulli’s principle of fluid dynamics, he theorized that the configuration would increase propeller efficiency, boosting engine performance and lift. While flight tests did not fully realize the projected gains, the concept foreshadowed the principles behind modern turbofan jet engines. Stipa later claimed that German engineers applied his ideas to jet-powered aircraft during World War II, including the V-1 flying bomb and the Messerschmitt Me-262.

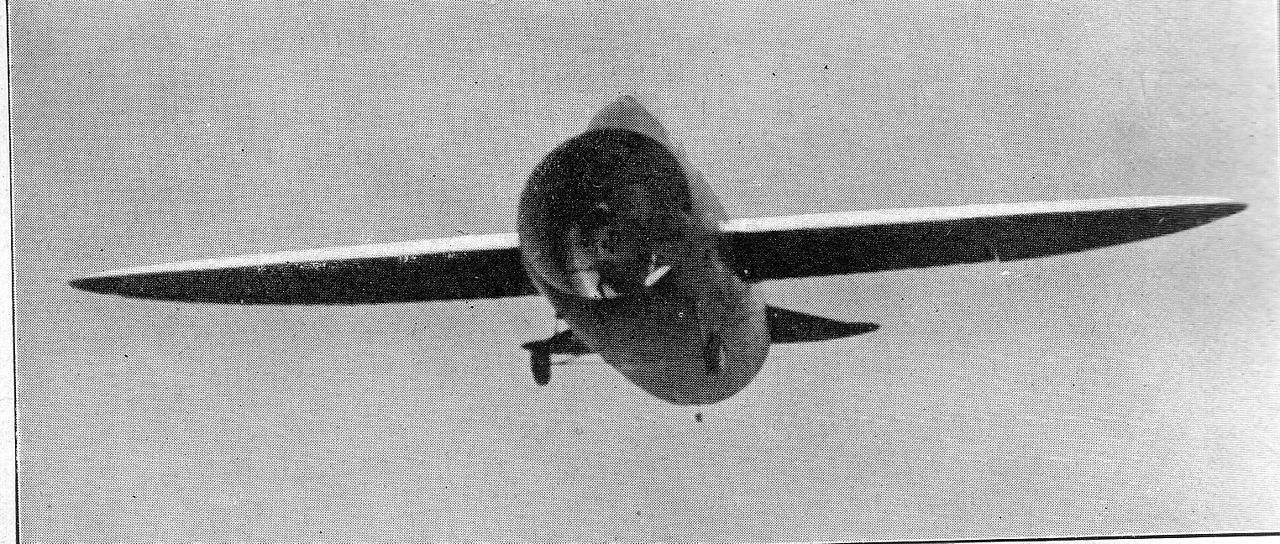

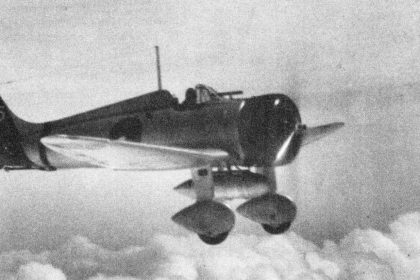

The Stipa-Caproni’s distinctive barrel-like fuselage made it instantly recognizable. Some criticized its appearance, while others appreciated the innovative purpose behind the design. Caproni test pilot Domenico Antonini conducted the aircraft’s maiden flight. Although flight tests showed only a modest improvement in climb rate, the Stipa-Caproni proved extremely stable and easy to handle. Its low landing speed of 42 mph and short takeoff and landing run of 590 feet made it particularly pilot-friendly.

The aircraft could accommodate one or two crew members and was powered by a 120-horsepower de Havilland Gipsy III four-cylinder inverted inline piston engine, achieving a maximum speed of 83 mph. Despite its unique design, the Italian Royal Air Force (Regia Aeronautica) opted not to pursue further development. The Stipa-Caproni’s legacy lived on in aeronautical engineering. A three-fifths scale replica was later built in Australia by Lynette Zuccoli and Aerotec Queensland. This replica successfully flew 660 yards at an altitude of 20 feet and is now on static display at the Toowoomba City Aerodrome.