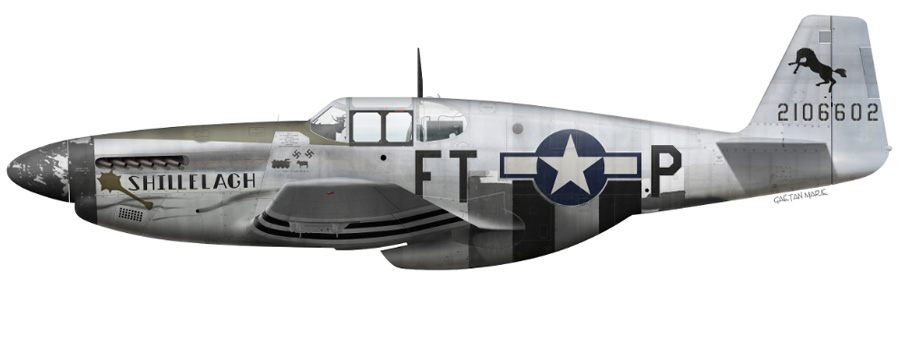

As regular readers will know, at time of writing, AirCorps Aviation is in the final stages of completing a magnificent restoration of a rare razorback Republic P-47D Thunderbolt for the Dakota Territory Air Museum. It is one of several world-class efforts which the now-famed restoration shop in Bemidji, Minnesota has rolled out of their doors over the past decade or so. Not an organization to waste any time, they are already working on a number of other projects, one of which they began last year for the Wings of the North Air Museum of Eden Prairie, Minnesota. This latest project is based around the wreck of a rare, early-model Mustang, P-51B 42-106602, nicknamed Shillelagh, which has an extensive combat history. Two of those who flew the Mustang also have interesting histories; David O’Hara, Shillelagh’s regular pilot who also named her, and Kenneth H. Dahlberg, the triple-ace and former Prisoner Of War who was at the controls on the fighter’s final mission. As already noted, Shillelagh’s rebuild began in earnest at AirCorps Aviation last year, so we are a couple of restoration reports behind the present state of progress. We will therefore catch you up to speed over the next few days so we can take up the story as it sits now. So without further ado, here is Chuck Cravens’ second report on Shillelagh – this one being from last fall…

P-51B Shillelagh Wings of the North Air Museum Project – Fall 2021 Update

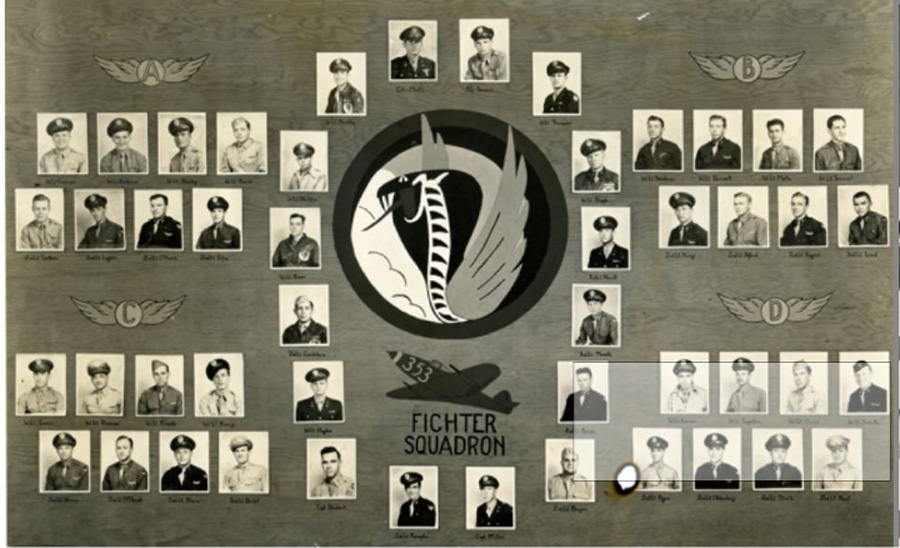

The restoration of Shillelagh honors Ken Dahlberg and his wartime story, as well as David O’Hara, to whom the Mustang was assigned. But a restoration like this also honors the entire squadron in which the Mustang served. It is interesting to not only follow Shillelagh’s mission history, but to also note how many different pilots flew this particular Mustang in combat.

Combat Missions

The 354th Fighter Group was known as the Pioneer Mustang Group, because they were the first unit to fly P-51B Mustangs in combat; beginning with a mission on December 1, 1943.

That first mission was also historic because it involved the very first combat sorties for the Merlin-powered Mustang variants. The mission was over the Pas de Calais area in France, and led by Col. Donald Blakeslee, the legendary 4th Fighter Group pilot, formerly of No.401 Squadron RCAF and No.133 Squadron RAF (one of the so-called Eagle Squadrons due to the preponderance of American pilots). The RAF entered combat with the Mustang Mark III (RAF nomenclature for the P-51B and C Mustang variants) on February 15, 1944, when No.19 and No.65 squadrons flew a similar sweep over the enemy-occupied coast on the French side of the English Channel.

On April 15, 1944, just four months after the Pioneer Mustang Group’s historic first mission, David O’Hara flew his new Mustang’s initial combat mission. He named his new Mustang Shillelagh after a traditional Irish walking stick which could also double as a club or cudgel for personal protection. Historically, there are many styles of stick which could be described as a shillelagh; the earliest known reference dates back over a thousand years.

When the English established plantations in Ireland during the sixteenth and seventeen centuries, there naturally arose a fierce resentment amongst the local population; resentment which often spilled over into conflict. During this period, the traditional short shillelagh club was outlawed by English penal codes, so the Irish responded by lengthening the shillelagh into a walking stick with a heavy end that could still be used as a club. Clearly, the shillelagh has deep rooted associations with Ireland, the fighting Irish, and Irish folklore.

The newly named and painted P-51B-10NA which David O’Hara flew for the first time on April 15, 1944 is the subject of Wings of the North Air Museum’s latest restoration.

Although P-51B-10NA 42-106602, Shillelagh (in several different spellings), was scheduled to fly 99 missions over its remarkable wartime career, four of these sorties had to be aborted prematurely (three due to coolant issues, and one for unspecified reasons).

According to the 353rd Fighter Squadrons’ official Combat Mission Schedule1 Shillelagh flew a total of 95 missions over enemy territory in just 5 months of 1944. Broken down on a monthly basis, this warhorse flew 10 missions in April of 1944 (one aborted on April 25), 20 in May (2 aborted – May 2 and 8), 28 in June (1 aborted due to unspecified cause), 29 in July, and 12 in August; the fighter was shot down on August 16, 1944.

The Mustang’s longevity in the combat theatre and staggering mission count is an amazing record, a real tribute to the proficiency of the 353rd Fighter Squadron’s ground crews… and its pilots.

1 354th Fighter Group Combat Mission Schedules Running from 1 April 1944 to 4 April 1945, From the National Military Archives Copied 2-27- 2006, courtesy of the Ken Dahlberg family

Shillelagh (or more properly Shilellaugh) wore the above scheme from April through August 7th, 1944. It always carried squadron marking letters FT-P. The FT identified it as a 353rd Fighter Squadron fighter and the letter P was the individual plane identification.

While we have yet to find the specific date when Shillelagh received new paint and a different spelling of its name in official USAAF records, an examination of the squadron’s combat schedule gives us clues to when these changes likely occurred.

From August 7 through August 10, there were 5 days when FT-P (the aircraft’s squadron code) did not fly in combat. This period is the most probable time when Shillelaugh visited a repair depot for maintenance – and to have the upper invasion stripes removed from the wing and fuselage.

The original D-Day invasion stripes were clearly visible from the air and ground, and were intended to prevent friendly fire during the D-Day invasion. Two months after the invasion, the greatest remaining threat came from nervous Allied ground gunners, and from enemy fighters. The upper stripes also compromised camouflage when on the ground. Therefore, removal of the stripes on the upper surfaces was allowed by the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). The upper stripes stood out when viewed from above, so they were removed to reduce the risk of enemy fighters spotting Allied planes and diving to attack from a position of altitude advantage. The lower stripes were retained so Allied ground gunners could easily recognize friendly planes. By August of 1944, most were gone.

By early August of 1944, 42-106602’s had completed 90 combat missions and needed a bit of refurbishment. Besides the maintenance and removal of the invasion stripes, the paint and nose art were also refreshed; the club being replaced with a mace, while the aircraft’s name changed from Shillelaugh to Shillelagh.

The Pilots Who Flew Shillelagh in Combat:

The Shillelagh restoration is a tribute to Ken Dahlberg, who was shot down in this Mustang, and to David O’Hara, who was assigned 42-106602 as his personal P-51.

The resurrected aircraft will also pay tribute to the 18 other pilots of the 353rd Fighter Squadron and 354th Pioneer Mustang Group who flew Shillelagh into danger over Europe in 1944.

In all, the list includes twenty different pilots who climbed aboard Shillelagh to fly on combat missions. Seven of those twenty pilots had attained ace status before the war ended, and four of them had double digit victory tallies.

Of course, the most frequent pilot was David O’Hara, since Shillelagh was assigned to him.

The following list, in descending order regarding the number of combat missions flown in Shillelagh, names the pilots who flew the fighter:

David B. O’Hara – 49 missions

Bruce W. Carr – 6 missions

Hayden H. Holton – 6 missions

Phillip D. Cohen – 4 missions

Richard H. Brown – 4 missions

John E. Bakalar – 4 missions

James P. Keane – 3 missions

William B. Debow – 2 missions

William T. Elrod – 2 missions

Carl M. Frantz – 2 missions

Theodore W. Sedvert – 2 missions

Russel S. Brown – 2 missions

Frederick B. Deeds – 2 missions

Kenneth H. Dahlberg – 2 missions

Felix M. Rogers – 1 mission

Glenn H. Pipes – 1 mission

(Unknown first name) Melton – 1 mission

Ira J. Bunting – 1 mission

Charles W. Koenig – 1 mission

Loyd J. Overfield – 1 mission

Combat mission reports from the 353rd Fighter Squadron, 354th Fighter Group provide us with the listings for every mission which P-51B-10NA 42-106602 flew. Shillelagh was assigned to the 9th Air Force on April 13, 1944, and then to the 354th Fighter Group, 353rd Fighter Squadron. The P-51B was assigned to David O’Hara and, as noted earlier, he flew the first listed combat mission with the 353rd on April 15, 1944. The Squadron code assigned to the aircraft was FT-P. O’Hara’s previous Mustang, also coded F-TP and named Shillelaugh, had gone missing in action on April 11 while being flown by Lt. Ralph A. Brown. Brown survived, was captured, and spent 13 months in Stalag Luft 1, Barth.2

353rd Squadron mission formations typically comprised between 4 and 16 fighters, with the formations being divided into flights; each flight (normally four fighters) was assigned a color code. These color codes indicated the position which a given pilot would fly within the formation. The 353rd’s combat schedules frequently list the flight color codes, always naming them in the same order of red, white, blue, and green; an order which would be easy for any USAAF pilot to remember. So it is a reasonable assumption that the lists which did not write out the color code of each flight probably followed the same convention.

Making this list in the order which the colors of the Americans are normally named, then adding green to make up the standard squadron maximum complement of 4 flights, makes sense.

2 American Air Museum in Britain. http://www.americanairmuseum.com/person/174859, Website accessed 9-21-2021

To view a list of the combat missions which Shillelaugh/Shillelagh took part in, please click HERE.

On 8/16/44 – Shillelagh’s last mission listed above – O’Hara was flying another Mustang, FT-T, on mission 205, also to Mantes – Etampes – Chateau Dun. After crashing FT-P on the 16th, Dahlberg escaped with help from the landowners of the French chateau nearby where he landed. No official Escape & Evasion Report, German J Report, or Missing Air Crew Report was ever filed for Dahlberg, meaning that the pilot did report back within 48 hours of being shot down, and most likely being within territory where the Germans would not have undertaken salvage operations. Dahlberg returned to combat on 8/25/1944, mission #215.

After Dahlberg’s crash, O’Hara received a new Mustang (with the FT-P squadron code) by 9/8/1944; this aircraft, P-51D-5-NA 44-13550, became The Shillelagh.

Shillelaugh Highlights

- The assigned pilot was 1st Lt David B O’Hara, O-744743. O’Hara flew a total of 84 combat missions from 20-December-1943 to 8-September-1944. 49 of these missions were flown in 42-106602, FT-P. During O’Hara’s combat time he had a confirmed air to air victory on April 8, 1944.2

- 42-106602 flew its first combat mission on 15-April-1944.

- 42-106602 flew a total of 99 combat missions. During this time period, O’Hara flew a total of 56 combat missions of which 48 were in 42-106602, FT-P

- Recorded as missing in action 8-17-1944

- Removed from AAF inventory 9-15-19443

Other notable events for Shillelaugh in 1944 include (in chronological order):

- 25-April: Encounter Report and Early Return with coolant problems

- 30-April: Battle Damage due to flak

- 2-May: Encounter Report (with another pilot) and Early Return due to rough engine

- 8-May: Early Return due to coolant problems

- 11-May: Encounter Report (with another pilot)

- 30-May: Encounter Report (with another pilot) and Early Return due to Oxygen troubles

- 6-June: Forced Landing at Stony Cross (Sta 254)

- 14-June: Encounter Report (with another pilot)

- 17-June: Encounter Report (with another pilot)

- 21-June: DNTO (Did Not Take Off, due to unknown mechanical problems)

- 25-July: Encounter Report with O’Hara for ground claims

- 1-August: Encounter Report (with another pilot)

- 16-August: Encounter Report (with another pilot) BOEVD Kenneth H Dahlberg/FRA

- 16 August: Lost (with Kenneth H Dahlberg)

- 17-August: Listed as MIA on the Individual Aircraft Record card

2 USAF Historical Study No. 85, USAF Credits for the Destruction of Enemy Aircraft, Albert F. Simpson Historical Research Center, Air University, 1978. Page 249

3 42-106602 FT-P Compiled by Ted Damick

Shillelagh Restoration

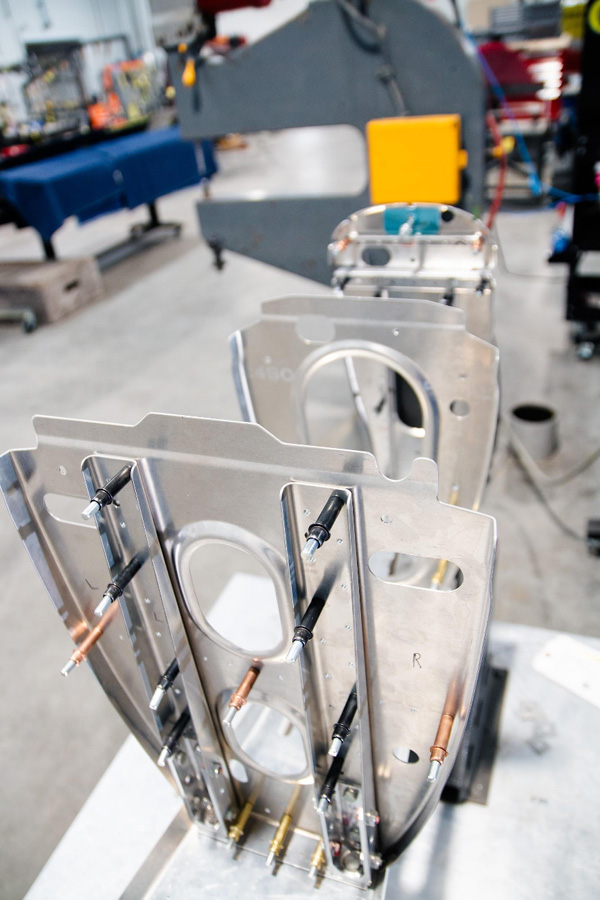

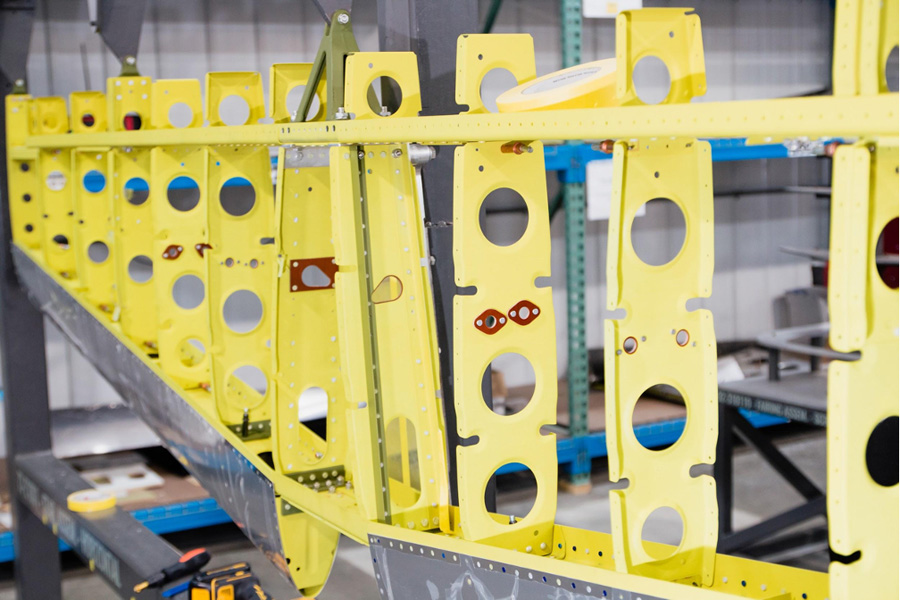

The restoration of P-51B 42-106602 Shillelagh is in the early stages of visible progress, but a great deal has been done in the area of original North American parts procurement and the fabrication of other parts before actual assembly can begin.

Tail Cone

One of the first major components to undergo assembly is the tail cone. The tail cone is one of the three main sections of a P-51’s fuselage.

Horizontal Stabilizer

The horizontal stabilizer is another of the early components to go back together in this restoration.

“Rosie the Riveter” Signatures

Upon inspection, sadly, these spars were not found to be in airworthy condition, but the signatures will be faithfully duplicated on their replacements.

And that is all for the second edition of Chuck Cravens’ coverage describing the restoration of Wings of the North Air Museum’s P-51B Mustang Shillelagh at AirCorps Aviation. We will publish the third installment from last fall in short order! Many thanks to Chuck Cravens and especially to AirCorps Aviation for their continued, long-time support!

Not 100% sure 354th FG followed USAAF potocol re: Flight ID for combat but an example for4th and 355th would be that within a squadron there were four Flights comprised of A and B and C and D Flights, in which pilots were assigned. An average of 10 pilots were assgned to each Flight – and obviously only 6 or so were actually assigned as ‘primary’ for a single squadron code. When more than 26 fighters were assigned to a squadron, a ‘Bar’ might be inserted under the squadron code. For example WR*B and WR*Bbar could exist in squadron.

The order of battle designation (i.e. use 354th FS/355th FG) was Red and Yellow comprise a Section, with Red Flight always lead and Yellow attached if the squadron was planned to separate locally into sections (like cover left and right on high side of assigned bomber box – and ess over the top cobvering each flight 6 o’clock). Blue and Green flights might maintain high trail on the box.

In every case A, B, C and D flights would rotate assignments into Red, Yellow, Blue and Green as squadron Ops and CO agree for the mission. The CO was ultimate authority and could select a pilot from C flight to fly in his Red Flight as his wing man for that mission.