The National Air and Space Museum is full of some of the most important airplanes in the world, each with its own story to tell. One of the most remarkable yet mysterious stories of any aircraft in the museum has been that of their Albatros D.Va, one of only two surviving original WWI Albatros fighters in the entire world. While it rests today in a place of honor, the journey it took to get to the Smithsonian has been shrouded in mystery, with generations of aviation historians dedicating themselves to find the airplane’s origin. Now, after over a century, and aided by the discovery of archival materials, we may finally unveil the complete story behind the plane called Stropp.

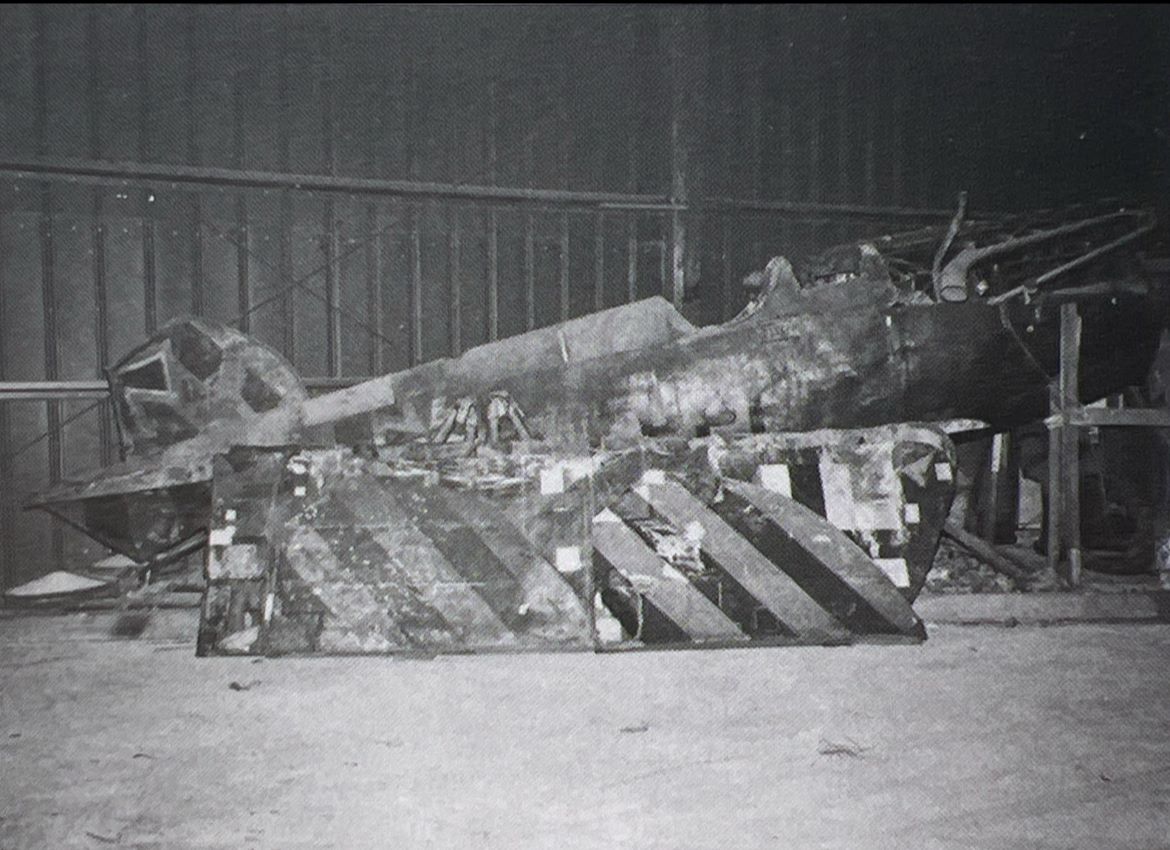

In January 1947, a short man visiting from Washington, D.C. walked into the De Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco, California’s Golden Gate Park. Though the museum by this point was becoming more of a fine arts museum, the man was not interested in paintings or sculptures, but rather he had come to this museum to find an airplane. His name was Paul E. Garber, and he was the curator of the Smithsonian’s newly founded National Air Museum but had been working with the Smithsonian since 1920. As he later related this account to the WWI aviation history publication Cross & Cockade, Garber asked an attendant if the museum still held an Albatros D.Va WWI fighter in its collection. The attendant replied that unfortunately, they did not. Having come far enough already, though, he decided to peruse through the museum to see if he could find any clues, occasionally taking peeks through storage room doors left open when no one was looking. In one of these rooms, Garber found the Albatros with its fuselage resting on packing boxes stacked above the floor and its wings hanging on the wall.

Satisfied with finding the aircraft, Garber approached the museum’s director, first apologizing for intruding in an employee’s-only area before asking about the status of the vintage fighter. The director told Garber that the aircraft had already been sold at auction for $500 and was no longer the property of the museum. Garber then learned that the buyer was George K. Whitney, the manager of Playland, a local seaside amusement park situated not far from Golden Gate Park. Soon, Garber established contact with Whitney and made an offer for the Albatros, citing its rarity and historical significance. Whitney agreed to sell the D.Va, but only on the condition that the Smithsonian pay for the costs of shipping and packaging. Garber agreed, but the Smithsonian would take two years to collect sufficient funds to have the Albatros shipped from California.

By August 1949, the funds were available, and the old Albatros was shipped to the Smithsonian’s temporary storage facility at a former WWII assembly plant at Orchard Place Airport, Park Ridge, Illinois (now O’Hare International Airport), where it was kept alongside more comparatively modern aircraft from the Second World War until 1951 when the Air Force evicted the Smithsonian to reuse the Park Ridge facility during the Korean War. Though Garber was able to develop a plot of land near Suitland, Maryland, that would become the Silver Hill Facility, Stropp would have to wait for over 25 years to finally receive a proper restoration, starting in January 1977.

Prior to the restoration, the Smithsonian knew very little about Stropp’s history. It had been exhibited in Liberty bond drives in 1918 and Victory Liberty Loan drives in 1919 before ending up in the De Young Museum. Historians such as Peter M. Bowers, who had personally seen the aircraft as a 12-year-old in 1930, helped provide descriptions of the aircraft in San Francisco, but that there was little else to go off on, not even a serial number. But as the restoration carried on, the Smithsonian’s specialists began finding some clues. In examining the chevron pattern of the faded yellow and green stripes on the tail section, it was determined that this was the distinguishing trait of an aircraft of Jagdstaffel 46 (or Jasta 46), one of the 40 Jastas established in 1917 as part of the Amerika Programme, intended to drastically increase the number of aircraft and squadrons in the German Luftstreitkräfte (Air Force) before the Americans arrived in significant numbers. Later, as the restorers began carefully removing the layers of paint, they discovered the aircraft’s serial number, D.7161/17, which marked it as one of the last 550 D.Vas built in the Albatros Flugzeugwerke headquarters factory in Johannisthal, Berlin, and was likely completed between February and April 1918. The destruction of many factory records during WWII, however, ensured that exactly when Stropp was completed remains indeterminate, but production stamps in the upper wing noted that at least this portion of the aircraft was under construction in December 1917 and January 1918. The lower set of wings were also believed to have been added to the aircraft after its capture, as although the fuselage and the upper wing had Eisernes Kreuz-style black crosses seen on German aircraft prior to the spring of 1918, the lower wings had balkenkreuz-style crosses which were ordered for all aircraft by April 1918.

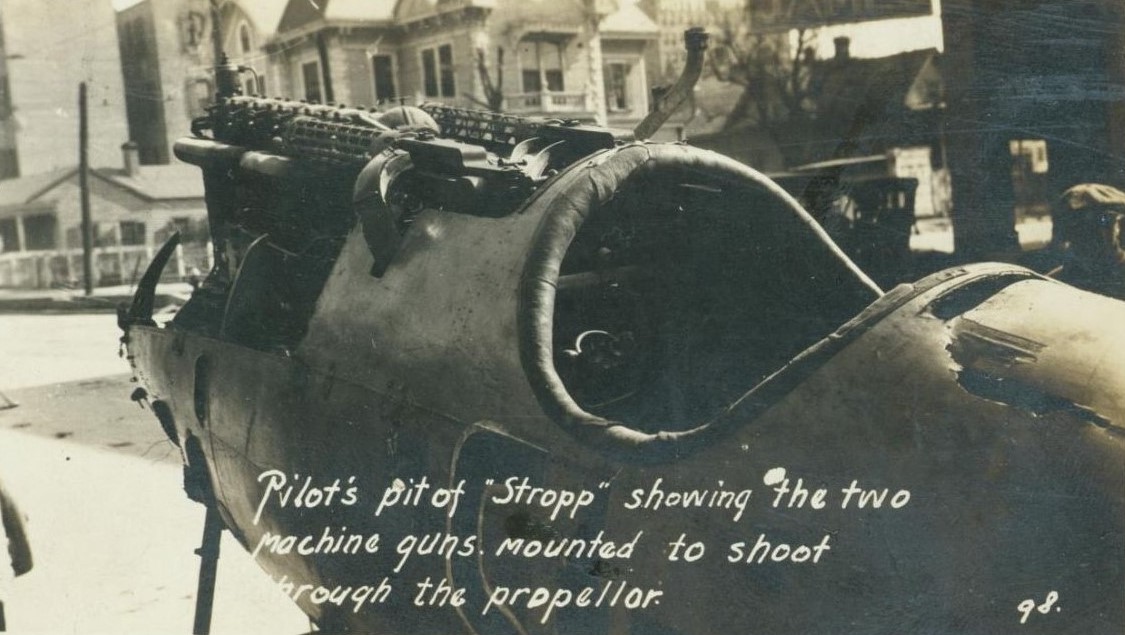

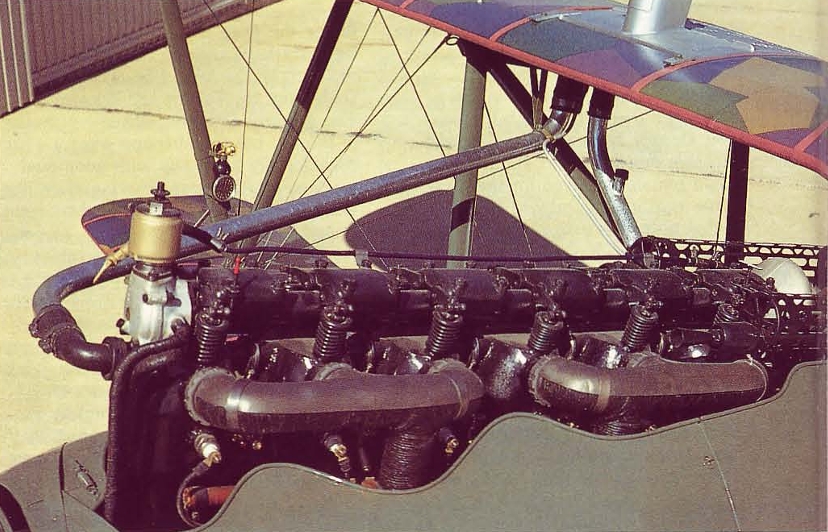

Perhaps the most intriguing discovery during the restoration was the trajectory of a bullet through some of the aircraft’s forward section. Lining up the trajectory with a metal rod, it was determined that the bullet had passed over the pilot’s right ear, entered the front right machine-gun mount, penetrated the front corner of the emergency fuel tank and stopped when it struck the right magneto. This would not be enough to single-handedly bring the Albatros down, provided everything else was in working order, but the loss of pressure in the emergency fuel tank meant a stop in the fuel flow from that tank, meaning that depending on the amount of fuel in the main tank, the pilot could have been forced to make an emergency landing. The fact that with the exception of the missing magneto, the damage was untouched also suggested that Stropp was never flight tested after entering Allied hands. Though a period-correct magneto was installed on the aircraft’s Mercedes D.III inline engine, the damage to the machine gun mount and the fuel tank was left in place.

By February 1979, the aircraft was fully restored, looking like new but with every effort made to adhere to the original standards of production. Since then, the Albatros has been on continuous display in NASM’s WWI gallery, which in 1991 was rebranded as the Legend, Memory, and the Great War in the Air gallery. In 2019, the ongoing renovation of the DC museum saw the aircraft brought for refurbishment and storage at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, VA until 2024, when it was returned to the National Mall in Washington, D.C. in preparation for the opening of the new gallery WWI: The Birth of Military Aviation, set to occur by 2026 (see this article for more details). Yet even after this restoration had revealed much about Stropp, many questions remained unanswered. Who was Stropp’s pilot? How and when was Stropp captured? And when did it arrive in the United States from Europe?

Several pilots have been thought to have flown Stropp with Jasta 46, but for years, and even in some circles today, the most commonly cited pilot from Jasta 46 has been Unteroffizier Erich Gürgenz, who had been listed in Jasta 46 casualty records as dying on April 4, 1918. The theory of Gürgenz being Stropp’s pilot came largely from the assertions of aviation historian James L. Kerr, who in the July 1986 edition of WWI Aero: The Journal of the Early Aeroplane, concluded that Stropp was shot down while being flown by Gürgenz on April 3, 1918, landing mortally wounded behind the lines of the British 18th Division at Marcelcave, just east of Amiens, and dying the following day, just as the Jasta 46 casualty reports indicate.

However, in a cruel twist of fate, the report that Kerr cited, which was filed by a British Area Intelligence Officer, and featured both an account of Stropp being shot down by a French fighter and original sketches of its markings, was the invention of one Rodney Gerrard of England, who was infamous among WWI aviation historians for distributing “original” documents from the personal collection of an unnamed British WWI officer when in fact they were entirely fictional or highly embellished accounts, and the purportedly “original” sketches were in fact based off those applied to Stropp during its restoration in the late 1970s. The last nail in the coffin for the Gürgenz theory was the fact that no Red Cross records ever mentioned an Unteroffizier Erich Gürgenz as having been in Allied custody, and a thorough look into Jasta 46’s casualty records report that Gürgenz died in a crash at Lieramont, the location of Jasta 46’s airfield from March to July of 1918. With Gürgenz ruled out, aviation scholars were forced back to square one as to which pilot from Jasta 46 flew Stropp.

In recent years, French historian Christophe Cony, and American historians Charles Gosse and Greg VanWyngarden began looking into the history of Stropp, building upon the groundwork laid before them by WWI aviation historians going back to the first scholarly articles on Stropp in the 1960s. With greater access to French archives previously untapped by American historians such as Gosse and VanWyngarden, Cony went through the records of the Service technique de l’Aéronautique (STAé; Technical Service of Aeronautics), the French state body in charge of aeronautics during WWI, and whose airfield and testing facilities at Vélizy-Villacoublay were used to test not only new French designs but also to evaluate captured German aircraft.

During his search Cony found a document in the archives of the STAé dated May 29, 1918, titled State of German airplanes arriving from May 19 to 25, 1918, which was signed by Alfred Caquot, Director of the Technical Section of Aeronautics, recounts the serial numbers and conditions of the German aircraft arriving during that time at Villacoublay. One passage reads as follows when translated from French to English: “ALBATROS n° 7161 type D.V.A. arrived on the 23rd coming from PARK 8 with engine and accessories – aircraft in fairly good condition the 2 lower planes were broken due to poor disassembly – aircraft sent and accompanied by exact delivery note.” This proves that Stropp (serial number D.7161/17) was in Allied custody by May 23, 1918, and Park 8 was the aeronautical section for the First French Army operating in the Somme, giving an approximate area to search for records of a German fighter brought down intact behind French lines.

In examining the records of other captured aircraft brought from the front to Villacoublay either by train or by truck, Cony notes that it typically took between three to twelve days for the aircraft to complete these overland journeys. In examining the records for squadrons assigned to the First French Army’s sector, Cony discovered a report from Escadrille Spa.153 which noted that a single German scout (fighter) was forced to land near the commune of Ailly-sur-Noye on May 19, 1918, with Spa.153 pilots Sous lieutenant (2nd Lt.) Andre Barcat and Maréchal des logis (Sergeant) Henri Arrault, sharing credit for the victory. At the time, MdL Arrault was a new pilot in the squadron, and like several other new pilots with Spa.153 on that day, he was being taken on a supervised combat training flight, and S/Lt. Barcat was guiding him on an afternoon flight after intelligence reported that German aerial activity was minimal. Then at 2800 meters (9,186 feet), Barcat and Arrault spotted a lone German fighter and in the ensuing aerial combat, forced the German to land on the road between Ailly-sur-Noye and Moreuil, with the pilot being captured by French ground forces.

But what do Jasta 46’s casualty records have to say about losses on May 19, 1918? A quick look into these records reveals that in fact, two airmen failed to return after sortieing out from Lieramont. These are listed as Oberleutant Hans Witt and Leutnant Alois Weber. Witt was reported to have been killed in action on this day over Villers-Bretonneux, as Jasta 46 engaged in dogfights with pilots of No.84 Squadron, Royal Air Force, which included South African ace Captain Anthony Beauchamp Proctor, who reported shooting down an Albatros at around 10:00 am, and three more around 6:35 pm local time. Witt’s plane crashed into the Allied sector held by the 47th Battalion of the Australian Army, and they report that the German pilot was “quite dead” and that he had a wooden leg. The Australians buried him at the front, but not before taking the prosthetic leg, where it eventually wound up in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, though it would take nearly a century for the AWM to uncover Witt’s connection to the artificial limb in their collection.

Meanwhile, Alois Weber, a reserve lieutenant from Kassel, was noted to have been captured on May 19, 1918, both in official French military reports and in International Red Cross documents. It seems the Germans, however, were not made aware of his capture until October 1918. After the Armistice, Weber returned to Germany, where he became an operating engineer. Little else is known about the remainder of Alois Weber’s life, but it seems it was a quiet one after WWI. He married in 1926 and died in 1973, aged 80. Ironically, Weber also outlived the two French pilots who forced him down. S/Lt. Andre Barcat was later killed in a dogfight over Malmy on July 16, 1918, and though Henri Arrault survived the war, left the French military as a sous lieutenant himself, and became a painter whose works were displayed in Paris at the Tuileries Gardens, he died of Hodgkin’s disease in 1930.

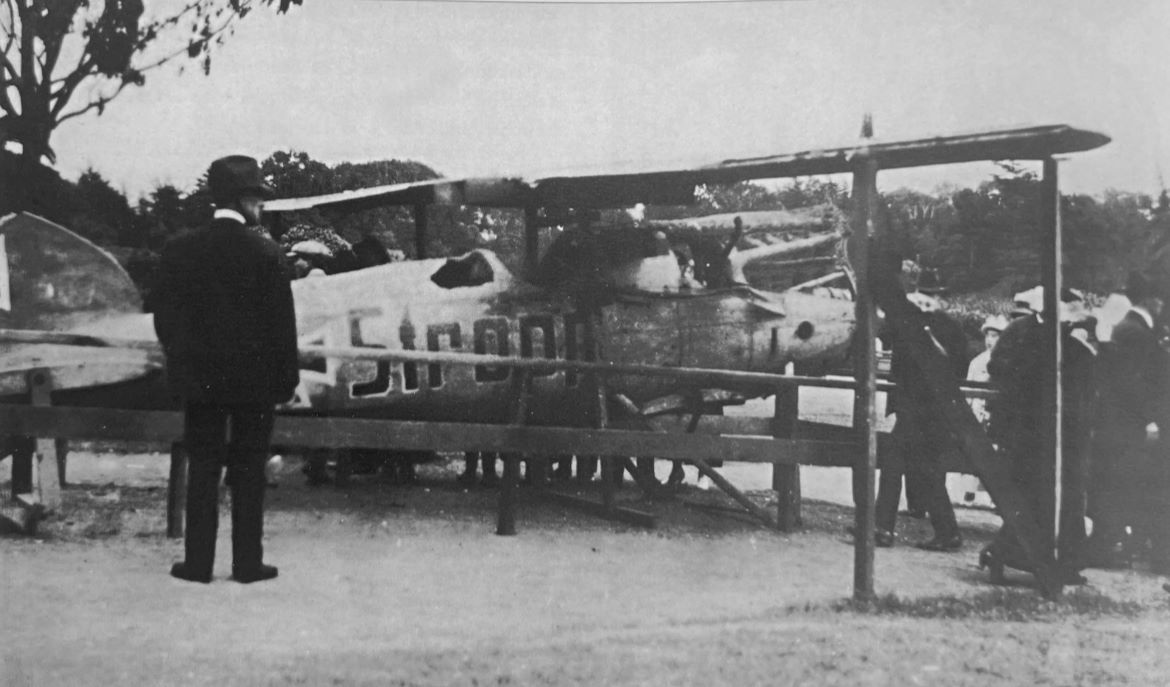

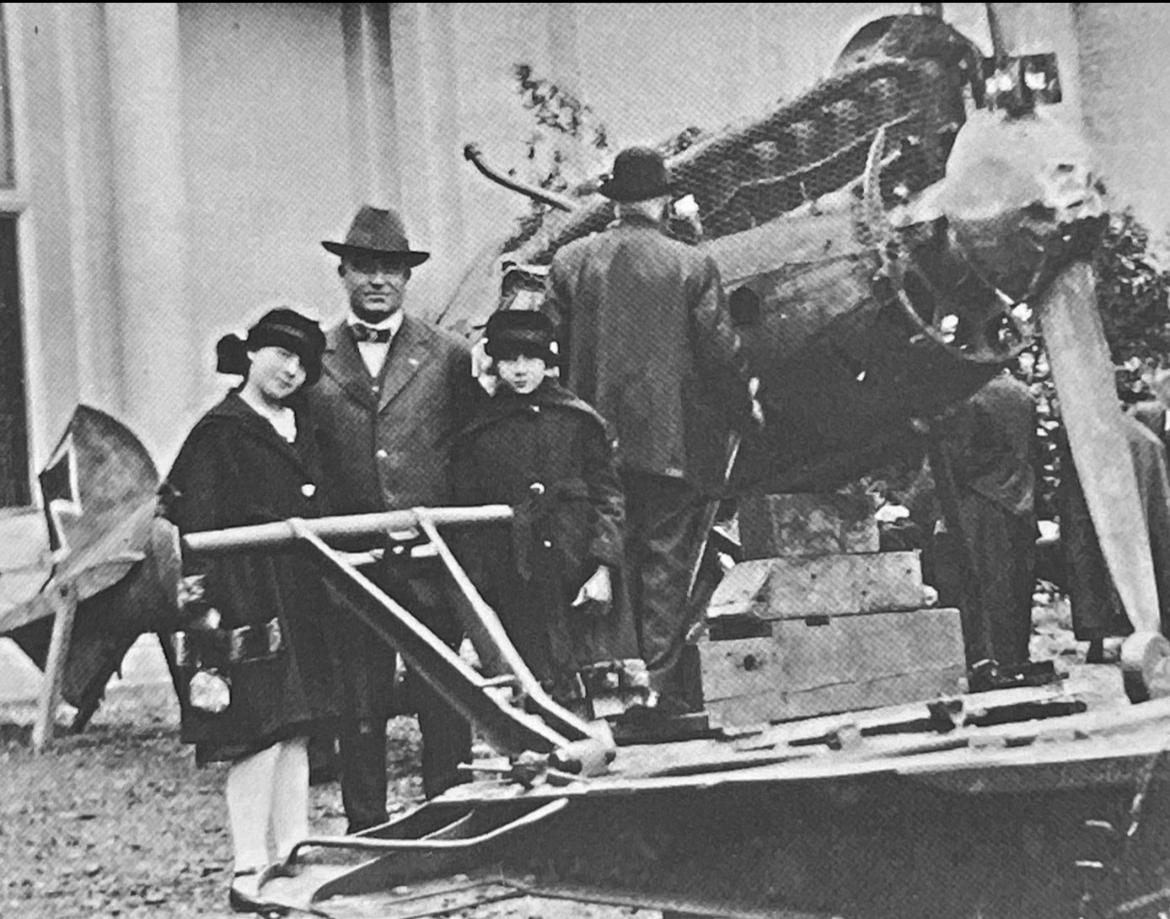

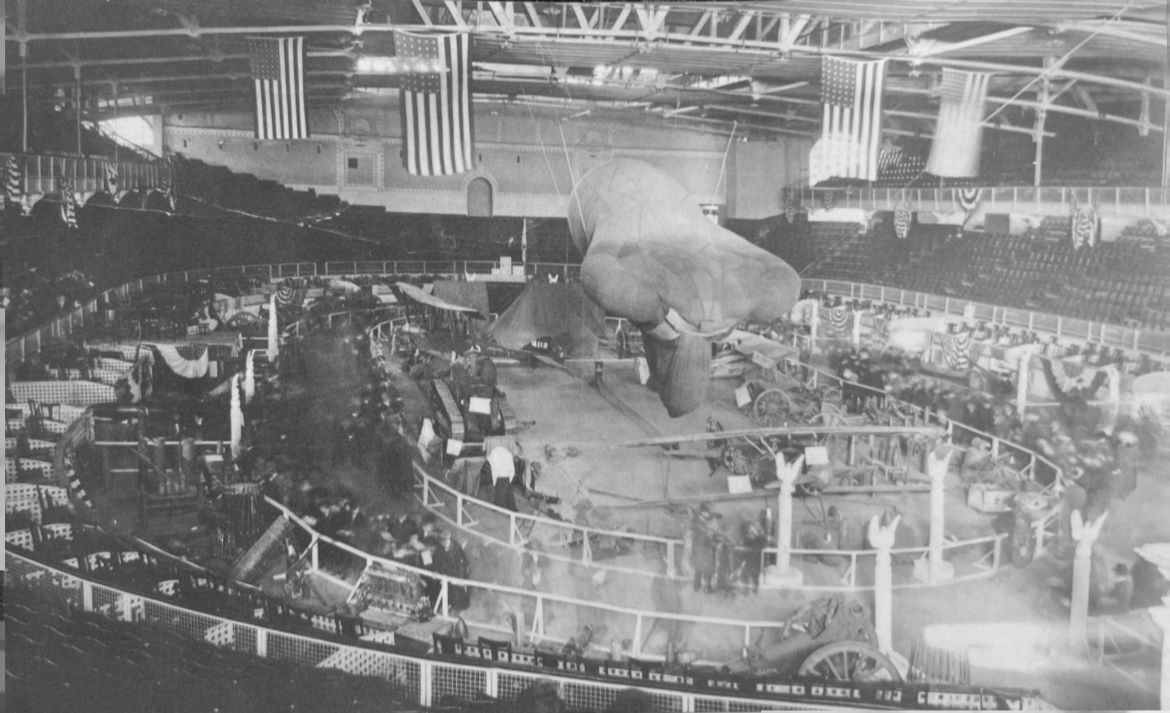

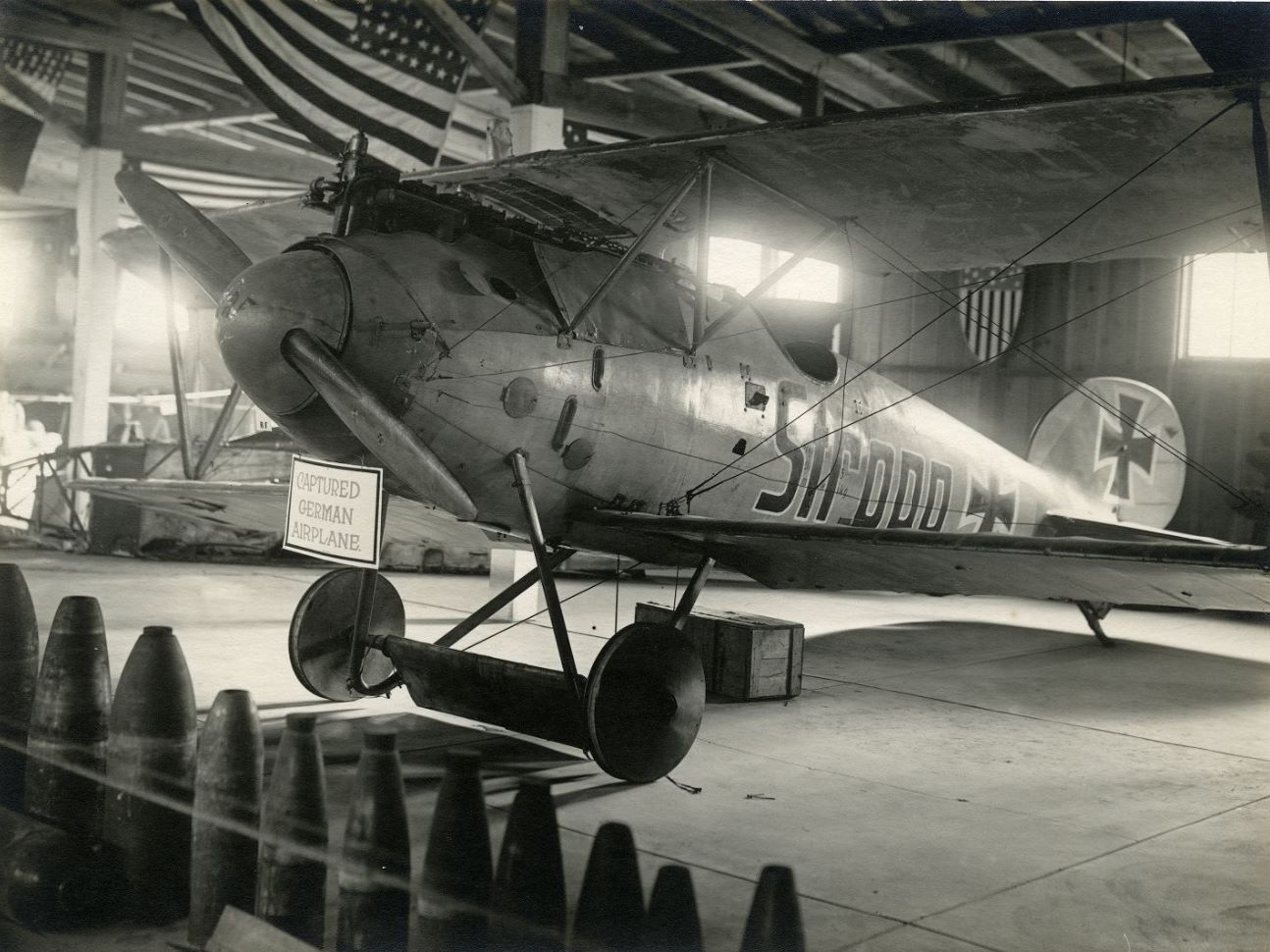

Determining when Stropp arrived in America is difficult to tell, but it appears that the aircraft was never flight tested by the French due to the combat damage to the machine gun mount, fuel tank, and right magneto going unrepaired, plus the damage to the lower wings from the bad disassembly. With other aircraft arriving at Villacoublay, and British Commonwealth forces test flying captured German machines of their own, Stropp was selected for public exhibition in the United States. The American government held traveling expositions to raise money across the country through the Allied War Exposition (AWE) tours set up by the War Expositions Bureau (WEB) and the Committee for Public Information (CPI) to show military equipment to the American public, who were far removed from the fighting in Europe, with the war being seen through newspapers, propaganda films, and letters back from their boys “over there.” It is from these tours meant to sell Liberty bonds that the earliest photographs of Stropp show the aircraft on display at the Cotton Palace in Waco, TX, in early November 1918. At this point, the aircraft is still intact, with the exception of its original wheels and tires being replaced with solid wooden ones. The aircraft was later displayed at expositions in Kansas City, MO, and Houston, TX, alongside other items ranging from haversacks, artillery guns, and other airplanes, from a SPAD VII painted as the one flown by Georges Guynemer, a Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2 painted as the one used by Frederick Sowrey to shoot down Zeppelin L 32 over England on September 24, 1916, and the fuselage of an Albatros D.III, along with a Caquot observation balloon. In the catalog for the exposition in Waco, Stropp was listed as part of the French exhibition with the inventory number ‘112 RF-Albatross Aeroplane.’ It is believed that the code ‘RF’ meant ‘République française.’

By March 1919, the AWE tours had come to an end, but even though a ceasefire was declared, Stropp would be included as part of a train tour of California, Arizona, and Nevada from April 12 to May 10, 1919. Starting in San Francisco, the Victory Liberty Loan tour made 115 official stops, in cities and towns such as Minden, NV, Carson City, NV, and Phoenix, AZ, with the tour concluding in Stockton, CA. During both the AWE tour from 1918-1919 and the Victory Liberty Loan train tour, the Albatros deteriorated more and more at nearly every stop. Little care was made into properly rigging the struts and wires for the wings, and the rudder went missing, along with engine cowling panels. Following the train tour, Stropp was displayed among assorted war relics in the open air at Golden Gate Park next to the new building intended to house the De Young Museum, named in honor of San Francisco newspaper owner M.H. De Young. On July 13, 1919, Stropp was officially transferred to the De Young Museum as a gift of the French government through Julius Kahn, representative for California’s 4th District. It would be here that Stropp would remain for the next thirty years until Paul Garber had it transferred to the Smithsonian.

There are still many questions to be answered regarding Stropp, but perhaps one of the most pertinent questions revolves around the origin of the name Stropp. While the Smithsonian originally believed it to signify the pilot’s name, Stropp is a very rare name for German families, and this theory seems unlikely. A more likely explanation for the name refers either to a Low German dialect nautical term for a ring or loop made of string, rope or wire or to a somewhat endearing team to refer to a young boy or dog deemed to be a troublemaker. Indeed, a short film from 1917 is titled Stropp!, and centers around the dog of the feminine main character. But without more definitive evidence, this question may yet go unanswered, even as the National Air and Space Museum’s new WWI in the Air gallery reopens in 2026, featuring the Albatros known as Stropp.

For further reading on the history of Albatros D.Va D.7161/17 Stropp, the author wishes to recommend Albatros D.Va: German Fighter of World War I (Albatros D.Va: German Fighter of World War I | National Air and Space Museum (si.edu)), by Robert C. Mikesh, curator of the National Air and Space Museum who oversaw the restoration of Stropp. This book is filled with excellent details and photographs about the restoration, and is the fourth addition to the museum’s Famous Aircraft of the National Air and Space Museum book series, as well as Stropp/Demise and Rebirth: New Findings on the Smithsonian’s Albatros and its Pilot, by Christophe Cony, Charles Gosse and Greg VanWyngarden, published in 2022 as part of the 37th Volume, Second Issue of Over the Front, the official journal of The League of WWI Aviation Historians (Home – Over The Front), and the research done in these and other publications has made this article possible, for which this author expresses his profound gratitude.