One of the most iconic galleries at the Smithsonian Institute’s National Air and Space Museum (NASM) on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. is by far the Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight gallery. Since the museum opened on July 1, 1976, this gallery has been home to some of the most significant aircraft in the history of aeronautics. Since 2019, however, all of the aircraft from the gallery have been removed during the renovation of the entire museum building, having been trucked to the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, VA, for refurbishment in the UHC’s Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar and to be kept in storage in newly-constructed storage modules at Udvar-Hazy meant to replace the older facilities at the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility in Suitland, MD (formerly known as the Silver Hill Facility). Now, as the remainder of the renovation work nears completion, here is an overview of the aircraft displays planned for the reimagined Pioneers of Flight gallery.

Perhaps the biggest change in the aircraft layout of the new Pioneers gallery is that the famed Spirit of St. Louis, flown by Charles Lindbergh from Roosevelt Field, Long Island, NY, to Le Bourget Field, Paris, France from May 20-21, 1927, will be displayed here as opposed to being suspended from the glass ceiling of the nearby Boeing Milestones of Flight Hall as it has since 1976. In an article published in the Summer 2023 issue of Air and Space Quarterly, Dorothy Cochrane, curator of the Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight gallery, explains the reason for moving the Spirit of St. Louis: “Even though the Museum’s ongoing renovation of the Boeing Milestones of Flight Hall has installed glass ceilings and walls that offer protection against the aging effects of ultraviolet radiation, we decided it was time to further shelter the fabric-covered airplane (the Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight gallery has far less exposure to sunlight). And moving the Spirit of St. Louis to its new space enables us to display the aircraft with some charming vintage memorabilia, further evidence of the public’s fascination with Lindbergh and his airplane.” The Spirit of St. Louis will be front and center of the newly reimagined gallery and will be in closer proximity to visitors from around the world.

Suspended behind the Spirit of St. Louis will be the Douglas World Cruiser Chicago, which led the first aerial circumnavigation of the Earth in 1924. Manufactured in Santa Monica, CA, and based off Douglas Aircraft’s DT torpedo bomber then in service with the US Navy, the Douglas World Cruisers (DWCs) were purpose-built to fly around the world to demonstrate not only the advances in aviation but also to promote the U.S. Army Air Service, which found itself on the receiving end of post-WWI budget cuts from a firmly isolationist Congress. Four DWCs were ready by March 17, 1924, being christened the Seattle, the Chicago, the Boston, and the New Orleans. Setting off from Seattle, WA, the Chicago and the New Orleans arrived back in Seattle on September 28, 175 days later. Although the Seattle crashed into the side of a mountain in Alaska and the Boston capsized and sank just off the Faroes after being forced to land in the rough seas of the Atlantic, not a single crew member of the DWCs was killed during the flight around the world. In recognition of the flight, the Chicago was flown to Washington, D.C. on September 25, 1925, to be donated by the US Army Air Service to the Smithsonian, where it has been part of the institution’s collection for 100 years. As a result of its airplanes being the first around the world, the Douglas Aircraft Company rebranded its logo in the style of those painted on the DWCs and adopted the motto “First Around the World – First the World Around.”

Other aircraft set to make their returns to the reimagined Pioneers of Flight gallery include the red Lockheed Vega 5B flown by Amelia Earhart to become the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic. Earhart had already gained fame for becoming the first woman to fly across the Atlantic, though as a passenger aboard a Fokker Trimotor called the Friendship, despite already being qualified as a pilot in her own right. Determined to make a solo crossing, she acquired a Lockheed 5B Vega which she would nickname as her Little Red Bus. Upgrading the aircraft at the Fokker Aircraft Corporation of America’s factory in Teterboro, NJ, with a supercharged Pratt & Whitney Wasp radial engine and an increased fuel capacity, Earhart flew the Little Red Bus to Harbor Grace, Newfoundland, where she set off on the evening of May 20, 1932, five years to the day Charles Lindbergh left New York’s Roosevelt Field for Paris’ Le Bourget Field, which was also Earhart’s intended destination. However, Earhart encountered bad weather, including heavy icing and fog, and suffered mechanical failures in the form of a failed altimeter, a fuel leak, and a damaged exhaust manifold. Nearly 15 harrowing hours after leaving Newfoundland, Earhart landed in a field near the village of Culmore, Londonderry, Northern Ireland. A stunned farmhand named Dan McCallon asked her, “Have you flown far?” to which she calmly replied, “From America.” Though she hadn’t made it to Paris, she was still the first woman to fly the Atlantic solo, and she received a hero’s welcome home in America. Three months later, between August 24-25, 1932, Earhart became the first woman to fly solo and nonstop across the North American continent in NR7952, flying from Los Angeles to Newark, New Jersey in 19 hours, 5 minutes. Seeking better performance for new records, Earhart purchased a newer Vega, and donated NR7952 to the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, PA, where it remained on display until it was transferred to the NASM in 1966. Like the Spirit of St. Louis, the Little Red Bus is to be displayed in companion with artifacts associated with the famed aviatrix, from her leather flying coat to a flight jacket of the Ninety-Nines, the long-running women’s aviation organization Earhart helped found back in 1929 when she was one of ninety-eight other founding pilots.

Opposite the Little Red Bus sits another Lockheed design in the form of a Model 8 Sirius, designed by Jack Northrop and Gerard Vultee, and which was flown by Charles and Anne Lindbergh. After marrying Anne Morrow, Charles taught her to fly, and in the Sirius, Anne would not only become Charles’ co-pilot but his radio operator and navigator. Together, they would fly their Sirius, registered NR211, on a great circle route from North America to East Asia, making stops in Canada, Alaska, Siberia, Japan, and China, with the aircraft capable of swapping out fixed landing gear for pontoon floats. In 1933, with Charles working as a technical adviser to Pan American Airways and Juan Trippe, the couple used the Sirius to scout the North Atlantic route from North America to Europe, where in Greenland, a young Inuit named the airplane Tingmissartoq, “one who flies like a big bird.” The Lindberghs flew the Tingmissartoq further east to Moscow, then down to the west coast of Africa and east coast of South America, accumulating over 30,000 miles flown over four continents on this second expedition. Later, the Lindberghs donated the Tingmissartoq to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, which displayed the aircraft until 1955, when it was donated to the Air Force Museum in Dayton, OH, before it was finally donated to NASM in 1959. Anne also used her experiences on these flights to write several books, including North to the Orient and Listen! the Wind, with editions of these copies set to be displayed alongside the aircraft, along with some of Anne’s radio equipment, flight clothing, supplies, and equipment carried by the Lindberghs on their flights in the Tingmissartoq.

Other pioneering aircraft that will go on display include the Curtiss R3C racer, in which Army Air Service pilot Lt. Cyrus K. Bettis won the Pulitzer Trophy at the 1925 National Air Races held at Mitchel Field, Long Island, NY, on October 12, and the same aircraft in which two weeks later, on October 26, Lt. Jimmy Doolittle won the Schneider Trophy seaplane race held in Baltimore, MD, and set three new records with the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). After appearing in the 1926 Schneider Cup race held in Hampton Roads, VA, Marine pilot Lt. Christian F. Schilt won second place in this aircraft before it was donated later that year to the Smithsonian. Loaned to the Air Force Museum in Dayton, Ohio for restoration and display before being displayed in the previous iteration of the Pioneers gallery, it had already been installed alongside the aforementioned aircraft and will be there on opening day.

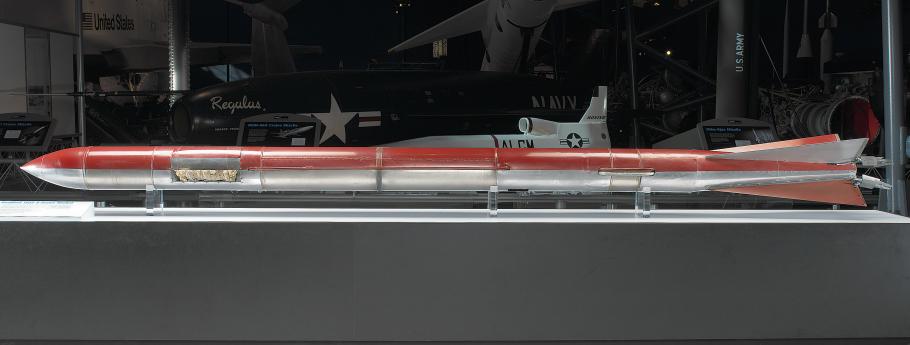

Fixed-wing aircraft are not the only aircraft returning to the Pioneers gallery. Also making its return will be the Explorer II high altitude balloon gondola, in which Army Air Corps Captains Albert William Stevens and Orvil A. Anderson, sponsored memberships to the National Geographic Institute, lifted off from the Stratobowl in South Dakota on November 11, 1935, and reached an altitude of 72,395 feet before landing in an open field near White Lake, South Dakota. The flight was also notable in that with Captain Stevens being an Army photographer, he took the first photographs showing the division between the troposphere and the stratosphere and the actual curvature of the earth, and its progress was the subject of a live radio broadcast throughout the flight. Meanwhile, rocket advancements made by American physicist Robert Goddard will also be commemorated in this new iteration of the Pioneers gallery. Goddard became famous in the scientific community by creating the first liquid-fueled rocket, which flew on March 16, 1926. Goddard would conduct further experiments out of Roswell, New Mexico, with financial backing from Charles Lindbergh and Harry Guggenheim. One of these rockets, his 1935 A-Series rocket, will be displayed in the new Pioneers gallery after previously being on display at the Udvar-Hazy’s Rockets and Missiles gallery.

Representation of the advances made by African American pilots in the 1920s and 1930s will also be making a return to the gallery. One item that will be on display is a copy of Black Wings, a 1934 book written by William J. Powell in order to encourage African Americans to pursue aeronautical careers in piloting, aircraft design, engineering, and mechanics, along with an image of Bessie Coleman’s international pilot’s license, which she earned in France after facing racial and gender discrimination in America that prevented her from obtaining a domestic pilot’s license. Also on display will be the flying suit, googles, and helmet worn by Chauncey Spencer on his 1939 roundtrip flight with Dale Lawrence White in a rented Lincoln-Page biplane from Chicago to Washington, D.C. to showcase the flying abilities of African Americans to a segregated America. The attention their flight received in the black press placed pressure on Congress to include African Americans in the Civilian Pilot Training Program, paving a way for the men of the Tuskegee Airmen to earn their wings. Their impact was also made on a senator from Missouri they met in Washington named Harry S. Truman, with Truman later integrating the armed forces while serving as President of the United States in 1948. More on Spencer HERE.

Also returning to the gallery is the first Piper J-2 Cub built after the Taylor Aircraft Company was rebranded as the Piper Aircraft Company. Another general aviation design in the form of the Mignet HM.14 Pou du Ciel (Sky Louse/Flying Flea) will also be included in the Pioneers gallery, having previously been displayed at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center. While the HM.14 was the brainchild of Frenchman Henri Mignet and intended as a light and affordable airplane for the common man that unfortunately never shook the stigmatization it acquired after several high profile crashes due to a design oversight, the example in the Smithsonian was built for Powel Crosley, Jr., President of the of the Crosley Radio Corporation, who had read Mignet’s book Le Sport de l’Air and had his personal pilot, Edward Nirmaier, build the plane that would become the Crosley Flea. Using locally available materials and the assistance of Dan Boedeker and Herb Junkin, Nirmaier made the first flight of this aircraft on November 1, 1935, exactly one month after beginning construction on October 1. It was the first HM.14 built in the United States, and Crosley’s daughter Page soon christened the aircraft La Cucaracha (the Cockroach) with a bottle containing water from Kitty Hawk, NC, the site of the Wright Brothers’ first flights. After barely surviving a hangar fire in 1939, the aircraft was placed in a barn, where it was rediscovered by vintage aircraft enthusiast Patrick Packard in 1957, who donated it to the Smithsonian in 1960 minus its engine. In 1991, the aircraft was restored by Packard and Patti Koppa on behalf of the Experimental Aircraft Association, and with the opening of the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, it was displayed near the Boeing 307 Stratoliner until it was selected for display in the new vision of the Pioneers gallery on the National Mall.

One aircraft that will not be returning to the Pioneers of Flight Gallery, will be the Fokker T-2, the aircraft in which US Army Air Service pilots Jon Macready and Oakley Kelly made the first nonstop flight across the continental United States from May 2-3, 1923, flying from Roosevelt Field, NY, to Rockwell Field (now NAS North Island) in San Diego, CA. The reasoning for the T-2’s absence is that with the inclusion of the Spirit of St. Louis, the new arrangement in the gallery’s aircraft layout meant that there was not enough space to display both the Fokker T-2 and the Spirit of St. Louis, which along with the Douglas World Cruiser Chicago positioned behind it, now hangs where the T-2 once hung. Today, the Fokker T-2 is being held in storage at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, and the museum intends to reassemble the aircraft and display it at Udvar-Hazy following the completion of all gallery renovations in D.C., allowing NASM specialists to focus on resembling the T-2 and other aircraft set to be displayed at Dulles.

Currently, the museum estimates that the Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight gallery will be set to reopen to the public in 2025, along with the nearby Boeing Milestones of Flight gallery, while other galleries at the National Air and Space Museum’s National Mall facility are set to open by 2026. For more information, visit the National Air and Space Museum website.