Starting in 2015, the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum (NASM), located on the National Mall in the heart of Washington, D.C., has been undergoing the most extensive renovation in its history since the building’s opening on July 1st, 1976. In that time numerous aircraft, spacecraft, and other artifacts both large and small have been transported to the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, VA for storage and evaluation before their return to downtown D.C. While half of the museum’s galleries have since been reopened since the fall of 2022, the remaining half of the museum is still a further two years from completion, but already iconic parts of the collection are returning from Udvar-Hazy and are being prepared for long-term display.

Among the new galleries set to reopen during this phase is a new iteration of the World War I aviation gallery, now titled World War I: The Birth of Military Aviation. In addition to several original WWI aircraft the gallery will also feature various uniforms, aerial cameras, and other items relating to military aviation of WWI, some of which have been a part of the Smithsonian’s collection since the end of the war over a hundred years ago.

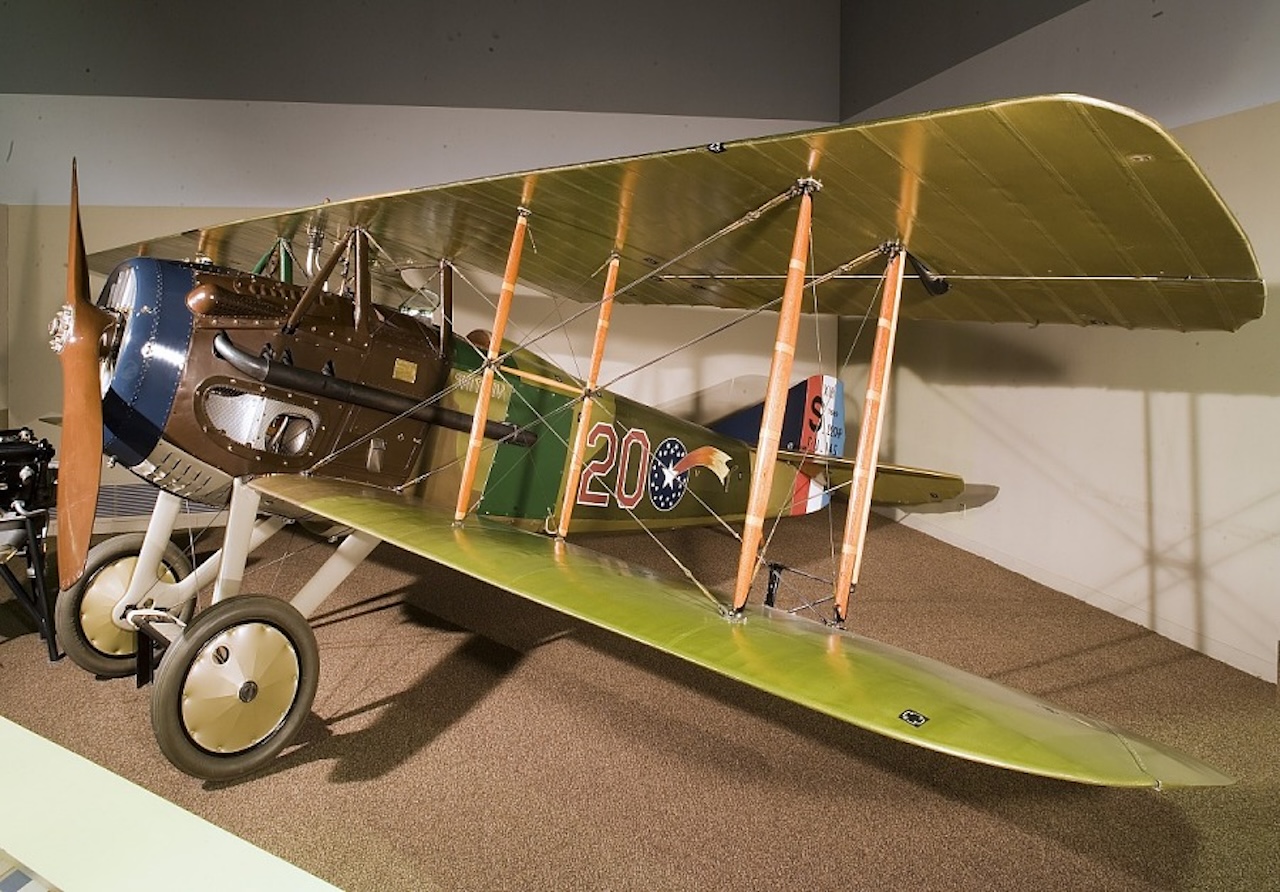

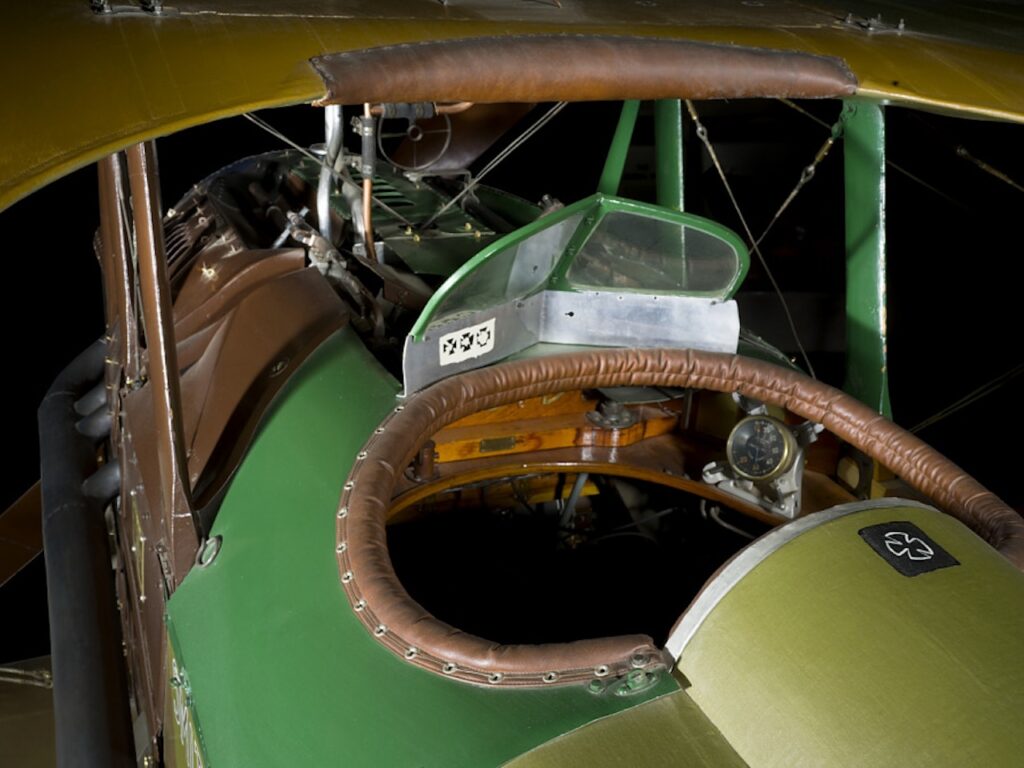

If there was but one French fighter of the First World War that was known for its combination of speed, ruggedness, and firepower, it was the SPAD XIII. Development of the earlier SPAD VII fighter, the SPAD XIII saw widespread use among the Allied aces of WWI, with the highest-scoring French, American, and Italian pilots flying this fighter into battle. The SPAD XIII in NASM’s collection is one of the most famous individual aircraft of WWI that remains in existence to this day. Originally built in France in August 1918 and issued with the tail number S7689, it was sent to the 22nd Aero Squadron of the United States Army Air Service, being given the squadron code ‘20’, and was assigned to Arthur Raymond “Ray” Brooks. Having been raised in Massachusetts, Brooks was a recent graduate of MIT when he enlisted for the Army Air Service to fight over France. Though Brooks had initially sought to name his plane for his finance, Ruth Marie Connery, he feared a flurry of off-color jokes at his and Ruth’s expense and instead chose to name his plane Smith after Smith College, the women’s college in Massachusetts where Ruth was enrolled at the time. By the time S7689 was assigned to him, Brooks had already had his previous Smiths shot beyond repair or totaled from flying accidents, and the aircraft became known as Smith IV.

Brooks would later claim one victory in Smith IV, while other pilots flying the aircraft would score a further five victories. Brooks himself would be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for fighting single-handedly against no less than eight Fokker D.VII fighters on September 14th, 1918, claiming four, but officially being credited with two of the Fokkers. By the time of the Armistice at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month in 1918, Brooks would be credited with six aerial victories and would spend the postwar years as a test pilot for Bell Laboratories, aiding in the development of radio navigation and air-to-ground communications systems. After retiring from Bell Labs in 1960, he remained active in numerous aviation organizations and in flying aircraft well into his 90s. When he died in 1991 at the age of 95, Ray Brooks was the last living American ace of WWI.

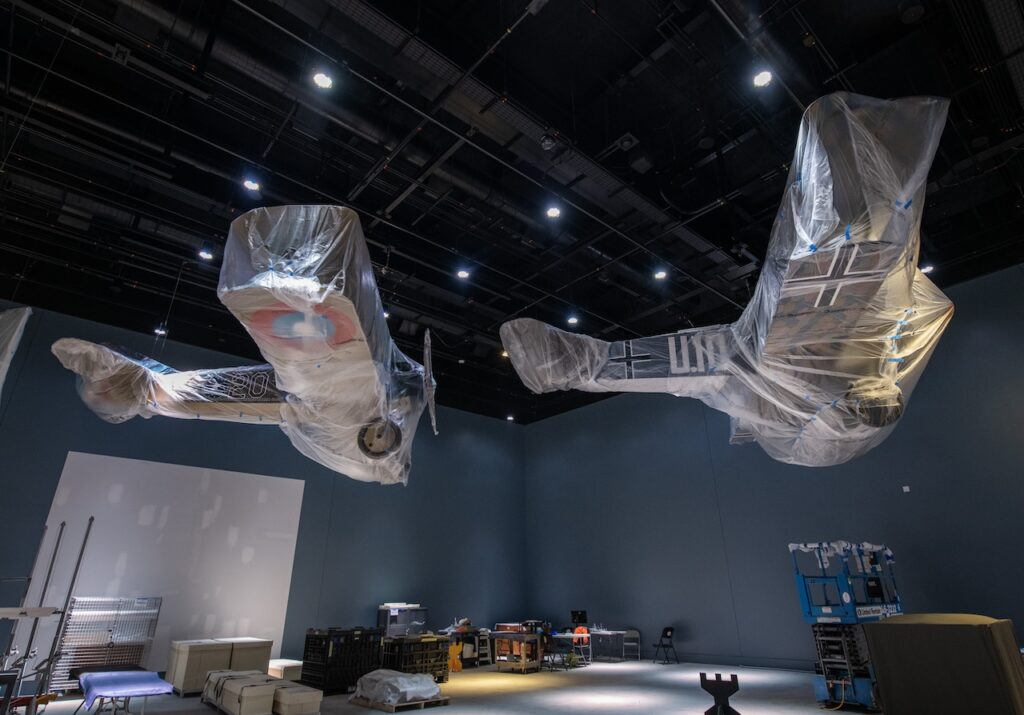

As for Smith IV, it went on to be one of two SPAD XIIIs brought to America after the war for a nationwide Liberty Bond tour before it was donated to the Smithsonian in December 1919. By the 1960s, however, the tires had degraded and the fabric was rotting, leading to Smith IV being placed into storage at NASM’s Silver Hill Facility (now the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility) in Suitland, MD where it would be fully restored from 1984 to 1986, complete with reproducing the black fabric patches with Iron Crosses signifying where German bullets had seared through Smith IV’s fabric surfaces. Ray Brooks was able to see his old aircraft fully restored and placed on display. Like all the WWI aircraft brought from Washington, Smith IV was refurbished in the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center’s Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar, where visitors could view the progress of the refurbishment efforts from a second-story glass mezzanine, before being driven back to the National Mall, along with a familiar foe to the SPADs and other Allied fighters, the Fokker D.VII.

The Fokker D.VII is widely regarded as one of the best German fighters of WWI, with its lightweight airframe consisting of wooden wings and a welded tubular steel fuselage, all doped in fabric. The aircraft was so well regarded, in fact, that Point A, Clause IV of the Armistice that ended the war stipulated the surrender of “1,700 airplanes (fighters, bombers) – firstly all D.7’s and night-bombing machines”. Several of these would see service after the war, but the example held in the NASM collections was originally constructed by the Ostdeutsche Albatros-Werke (East German Albatros Works, abbreviated OAW) in the city of Schneidemühl (now in northwestern Poland and known by its Polish name Piła). Donated to the Smithsonian by the War Department in 1920, the aircraft had landed at an American forward-operating airdrome east of Verdun on November 9th, 1918. According to the pilots of a detachment of the 95th Aero Squadron who were there (namely Capt. Alexander H. McLanahan, Lt. Edward Peck Curtiss, and Lt. Sumner Sewall) the pilot circled low over the field and landed after being waved down by the Americans on the ground, who then drew their sidearms on the German pilot, who offered no resistance and did not attempt to burn his aircraft to prevent its capture. After the German pilot was sent to a nearby artillery unit for further processing, the Fokker D.VII had the Kicking Mule insignia of the 95th Aero Squadron applied and flown to Paris for evaluation before eventually ending up in the Smithsonian, displayed alongside Smith IV in the old Aircraft Building (aka the Tin Shed) on the grounds of the Smithsonian Castle, and later in the Victorian-era Arts and Industries building.

For decades, the identity of the pilot of the Smithsonian’s Fokker and the significance behind the unique set of markings for U.10 on the fuselage and the top wing was unknown, but later research uncovered that the D.VII, flown as serial number 4365/18, was assigned to Leutnant Heinz Freiherr von Beaulieu-Marconnay of Jagdstaffel 65 (Jasta 65). Both Heinz and his brother, Olivier, had been members of the Prussian cavalry, with Heinz serving in the Tenth Uhlan Regiment, and Olivier in the Fourth Dragoons, leading to the Beaulieu-Marconnay brothers flying with the codes of their old cavalry regiments as their personal aircraft emblems: Heinz flying with U.10, and Olivier (who would become the youngest recipient of the Pour Le Merite) flying with the code 4D. U.10 was fully restored in 1961 and refurbished a second time in 1991. The new gallery will feature for U.10 and Smith IV suspended from the ceiling, as though in a silent chase through the air.

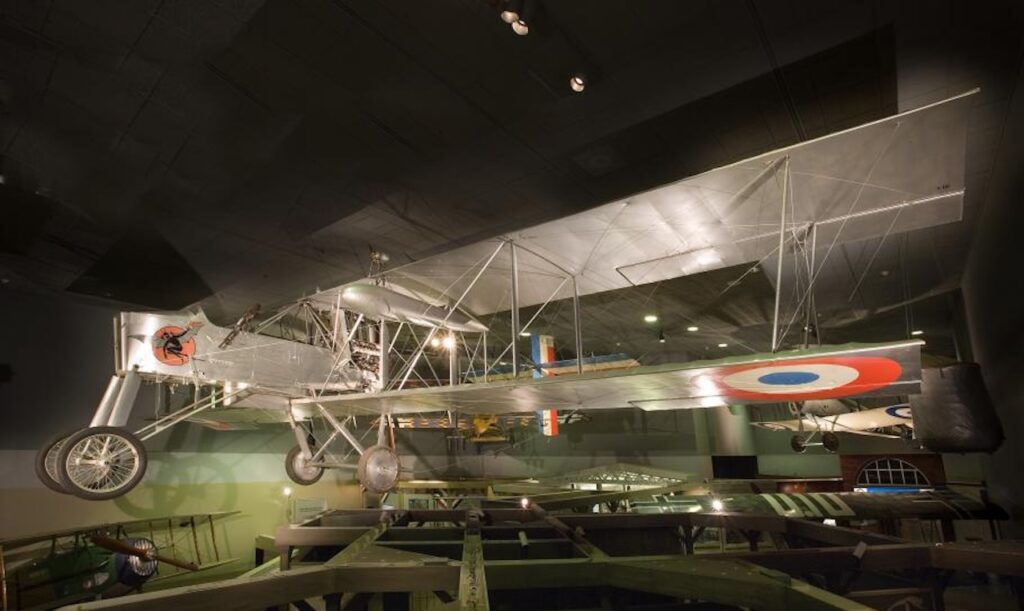

Another aircraft returning to the National Mall is the museum’s DH-4. Originally designed by Geoffrey de Havilland when he was the chief designer of the Aircraft Manufacturing Company Limited (Airco), the DH.4 served in the British Royal Flying Corps before it was reformed as the Royal Air Force in 1918. In spite of early teething issues, the DH.4 came to be a well-respected aircraft, with speed and maneuverability proving to be just as great an asset as its bombs and machine guns. But while British DH.4s, largely powered by the Rolls-Royce Eagle V12 engine, would become one of the most successful light bombers of the late-war period, the DH.4 saw fame across the Atlantic in the United States as well. After it was determined that the United States armed forces lacked any effective combat aircraft, the DH.4 was selected for mass production in American factories and shipment to the frontlines in Europe. While originally designed by the British, the American-built DH.4s (equipped with Liberty L-12 engines and redesignated DH-4) would become the only American-built aircraft to see combat over the Western Front. After the war, DH-4s remained in use with the US armed forces well into the 1920s and were further employed by the fledgling airmail carriers to blaze the trails that established many of the commercial air routes over America today.

The Smithsonian’s DH-4 was the first of its kind constructed in the United States, built by the Dayton-Wright Company in Dayton, OH. First flown on October 29th, 1917, it never saw combat itself but was utilized in over 2,600 experiments with the Army Air Service and the Dayton-Wright Company, including engine, propeller, and control tests that directly influenced modifications applied to DH-4s that served in combat. The Smithsonian’s aircraft was further distinguished when on May 13th, 1918 Orville Wright made his last flight as a pilot flying a 1911 Wright Model B alongside this DH-4, flown by Howard Max Rinehart. He then made a flight as a passenger in the DH-4 with Rinehart later the same day. Upon the aircraft’s retirement in 1919 it was donated by the US War Department to the Smithsonian. Restored from 1980 to 1981, it will demonstrate not only the contributions of American industry but to the reconnaissance role, a common mission for many DH-4s.

If there is any Allied fighter of WWI that requires no introduction, it would be the Sopwith Camel, whose instability was deadly for inexperienced pilots, yet in the hands of an experienced pilot, it could outmaneuver its opponents or dive away from trouble. The Camel in the Smithsonian, one of eight surviving originals, was the last example to have been manufactured in the Sopwith factory at Kingston-upon-Thames. The wider history of these aircraft was previously documented by Richard Mallory Allnut for this VAN article when this aircraft, and a Bleriot built by two Colorado teenagers in 1911, were donated through the estate of vintage aviation pilot and collector Javier Arango. Given the Camel’s status among the fighter aircraft of the First World War it has been confirmed that, after seven years on display at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, the museum’s example will go on display at the new WWI gallery at the National Mall.

Developed from the earlier Albatros D.II and D.III fighters, the Albatros D.Va was one of the most distinctive biplane fighters of the German Air Service during WWI. Like the earlier D.III, the D.Va borrowed the ‘V’ strut design found on French Nieuport fighters and featured a plywood fuselage. However, while the D.Va was a good overall fighter and was built in large quantities to face the growing numbers of Allied fighters flown by British, French, and American pilots, it did not offer a drastic increase in performance over its predecessors and held the lines in the air up until the arrival of the Fokker D.VII, though numerous D.Va remained in service up until the Armistice. The example in the Smithsonian, which bears the German word Stropp, is one of only two remaining original D.Vas (the other being in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra). Brought to the United States for War Bond exhibitions, it was donated to the de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco, CA, along with other wartime artifacts that were gradually deaccessioned from the collection as the de Young Museum came to focus on fine arts.

In January 1947 Paul E. Garber, then curator of the National Air Museum, traveled to San Francisco in the hopes of acquiring the Albatros for the Smithsonian. Though he was told by a museum attendant that no such aircraft matching his description was in the museum, he snuck a peek into an unlocked storage room and found the disassembled Albatros. After finding the de Young Museum’s curator, he apologized for going into an off-limits area of the museum before inquiring about the Albatros. As it turned out, the Albatros had been sold at auction for $500 to George K. Whitney, the general manager of a local seaside amusement park named Playland, where he intended to display the antique aircraft. Garber then found Whitney and offered to purchase the aircraft on behalf of the Smithsonian. Whitney agreed on the condition that the Smithsonian would shoulder the costs of shipping the aircraft back to Washington, D.C. When the aircraft was restored from 1977 to 1979, the serial number D.7161/17 was discovered on the tail and the aircraft was determined to have been flown as a part of Jasta 46 and was subsequently restored to said markings. When the WWI gallery reopens the Albatros will be displayed outside and above the gallery’s entry, along with a rare French bomber, the world’s sole complete example of the Voisin VIII.

Developed from earlier bombers and reconnaissance aircraft, the Voisin VIII was utilized primarily as a night bomber, attacking German industrial targets. Additionally, some Voisins were fitted with a 37mm Hotchkiss cannon for anti-air and anti-ground purposes, though these were not as effective as the French had hoped. The NASM’s Voisin was originally shipped to the United States in 1917, along with two other French bombers, a Farman and a Caudron G.4, for evaluation for American combat use. However, by the time these three airplanes were ready for testing in the summer of 1917, they were deemed obsolete due to the rapid advancements of combat aircraft. In July 1918, the three aircraft were offered to the Smithsonian for exhibition, and were delivered in September of that year, albeit with their engines, propellers, and armament removed. Originally displayed in the Arts and Industries Building until 1928, when it was placed in storage for the next sixty years. Finally, from 1989 to 1991, the Voisin was restored at Silver Hill, complete with an original Peugeot 8Aa engine transferred from the National Museum of the USAF.

While all of these aircraft have been confirmed to be on display in the National Mall, there are a couple of planes previously displayed at the National Mall that this author believes will likely go on display at the Udvar-Hazy Center, such as the Pfalz D.XII, Sopwith 7F1 Snipe and Royal Aircraft Factory F.E.8 reproduction on loan from the Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome in New York.

The new gallery is set to open in 2026, and is certain to provide a whole new insight into the role of aviation in the Great War, and how it came to shape military aviation to the present day. For more information, visit the Smithsonian’s website HERE.

Great article, Adam! Thank you for sharing the pics and stories of these fine old warbirds.