During World War II, before the age of computer-generated aircraft engineering drawings, thousands of skilled draftsmen created tens of thousands of drawings for every aspect of every model of aircraft produced—so precise and detailed as to allow different factories to create to the exact specifications needed, yet still as visually beautiful and striking as any fine art. Without the dedicated work of preservationists and archivists over the years, these drafting drawings may have been lost forever, yet thanks to the vision of a few, these drawings are being preserved and displayed not only as art, but as the valuable resources they are for the warbird community.

Previously, Vintage Aviation News interviewed Ester Aube and her work with AirCorps Aviation in cataloging the thousands of intricate drawings from North American factories across the country during WWII, part of which is now an exhibit called “Drafting: The Art of Aircraft Engineering in WWII” on display at the EAA Aviation Museum in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. (Read the story of how Ken Jungeberg discovered and saved the drawings HERE, and our last coverage of Aube’s work at the beginning of the project HERE.)

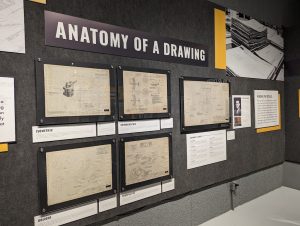

In April of 2023, Ester Aube finalized and installed an exhibit at the EAA museum using the drawings and telling the story of the draftsmen from North American and highlighting their contribution to the war efforts. When the collection was initially received from Ken Jungeberg, they had promised to do something to help get the story of the draftsmen out to the general public and get some of the drawings in public view so that people could enjoy and learn. The exhibit will be in the museum until September of 2025. “I chose some, cherry-picked some really amazing drawings to highlight in that exhibit,” says Aube. “And also was able to find family members of two of the draftsmen whose drawings are displayed and do a little bio about them, which is one of the neatest things, in my opinion.”

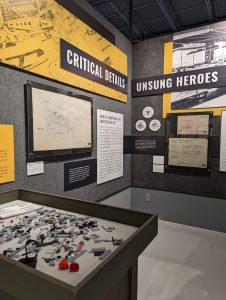

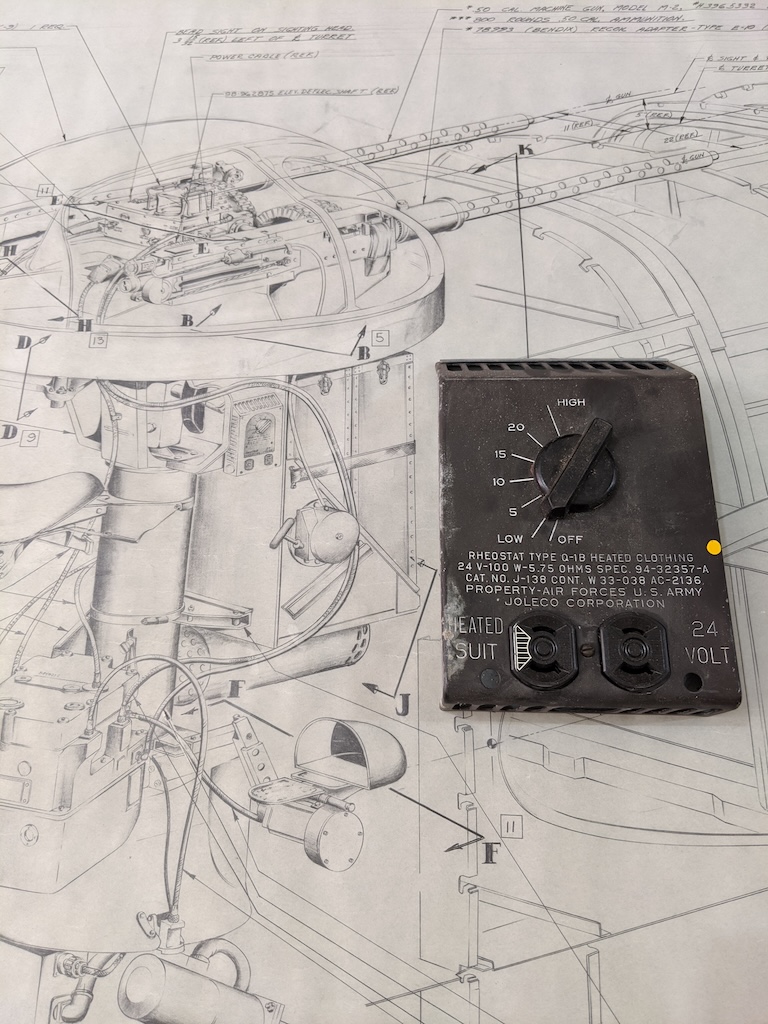

“It’s kind of become my passion project,” she says. “I’d really like to write a book about the draftsmen because they’re an overlooked demographic in the war effort. We always talk about Dutch Kindelberger and these kinds of lead engineers or people who are running the company, but there were thousands of these draftsmen who contributed to the war effort in a huge way. And we don’t really talk about the technical work that they were doing and the expertise that they had. And it’s a very fascinating side of World War II that I feel deserves to be told. And it really puts the drawings in a different light when you can see something that’s so technical.”

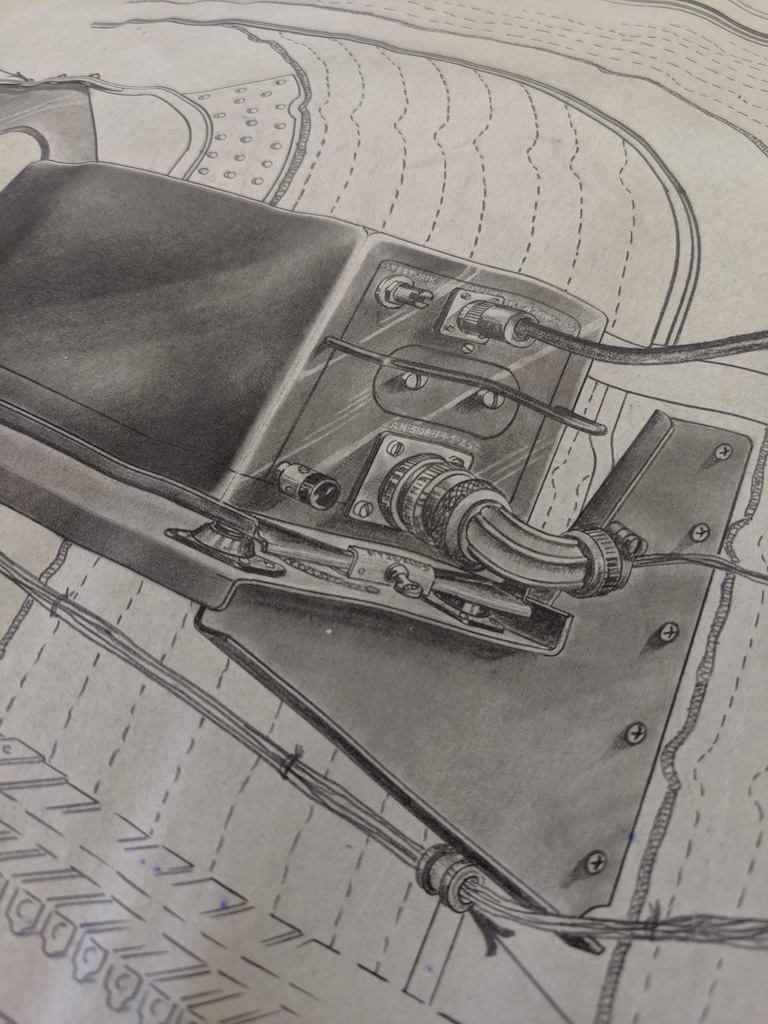

Her favorite example to date is the brake pedal that North American used in all of their most iconic aircraft. Tame rudder pedal used in the T-6, the T-28, B-51, and B-25. The man who made the drawing for the pedal was Clyde Moulding, and Aube was able to locate his family. She put his photo next to the drawing in the exhibit, feeling that it changed that item from something just purely technical, what many people would consider a boring item, into something personal and human.

“I am very fascinated by the connecting those stories and also connecting the family members of those drawings back to the work that their dad or grandpa or whoever produced during the war,” says Aube. “And most recently I’ve realized that there’s those guys who were in the drafting department, at least some of them, felt a level of guilt about not serving in active duty. And so part of this project for me is to, even if they’ve passed however many years ago, to kind of posthumously champion the work that they did and talk about how important it was and how they were really involved in the war effort in a very meaningful way.”

Down to a Science

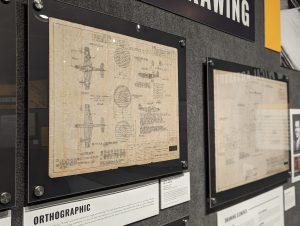

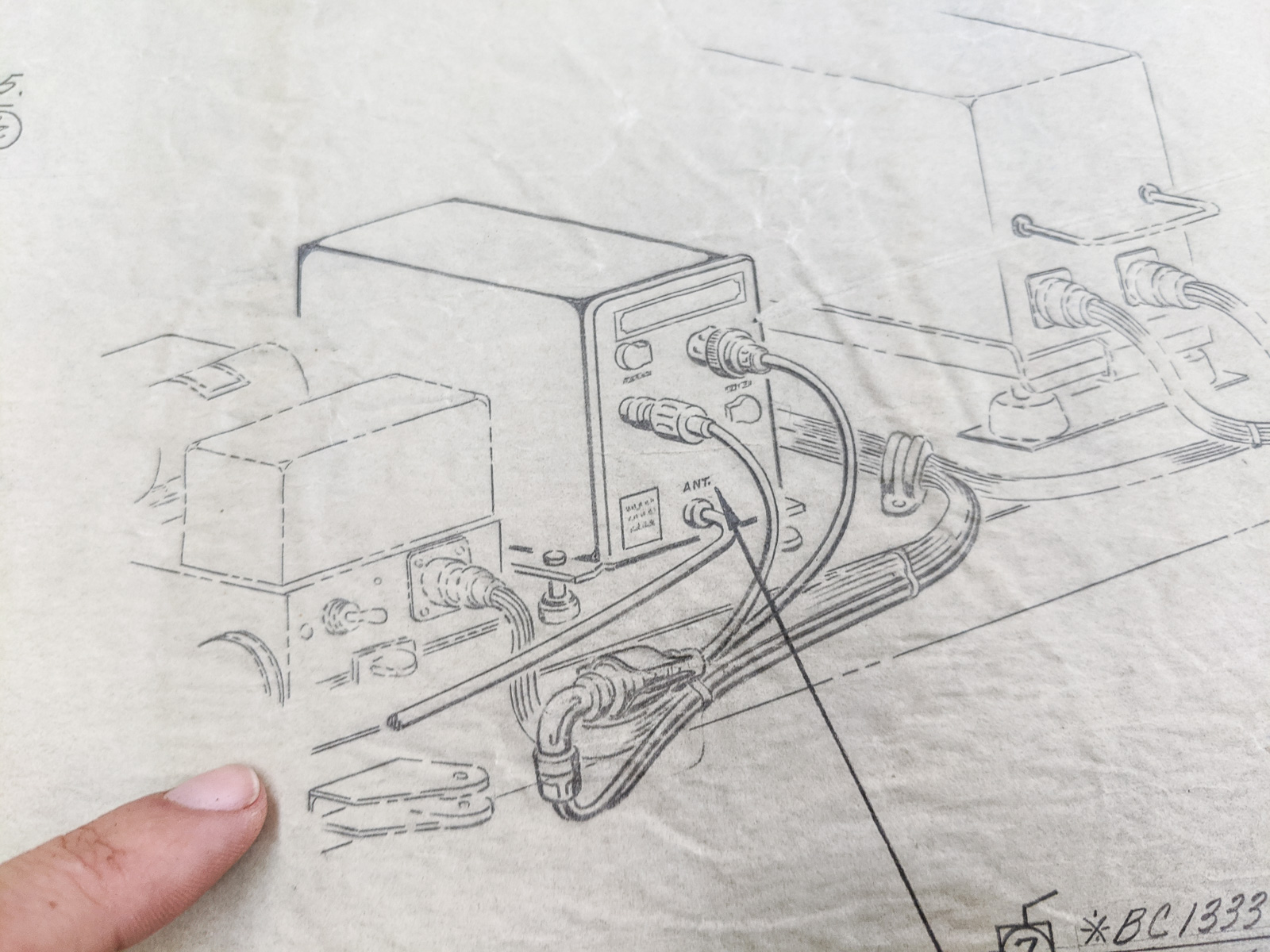

With so many drawings and aircraft to sort through, Aube started the project working on a specific aircraft, the P-51, because both AirCorps Aviation and the many aircraft in the warbird community would get a lot of benefit from such extensive original engineering drawings. At this point she estimates she has catalogued a little over 15,000 drawings just for the Mustang, and has also ventured into the smaller size drawings for the early B-25 models, which will be her next branch to catalogue. “The cataloging process is very labor intensive,” she says. “So I’m cataloging part number and the description, which under normal circumstances isn’t as important. But because this collection contains so many experimental and pre-production drawings, you have to catalog the description because that part number isn’t listed anywhere in a parts catalog or it’s not referenced.” North American did have a part numbering system, but all the pieces of data are needed or else the searchability is difficult. So part number, description, the date it was drawn, name of the draftsman, the material the drawing was done on, and the factory it was made in all are recorded during the cataloguing process. There are drawings from factories in Inglewood, Kansas City, Dallas, and even some from the Canadian Car Foundry in Ontario, Canada’s largest aircraft manufacturer during World War II.

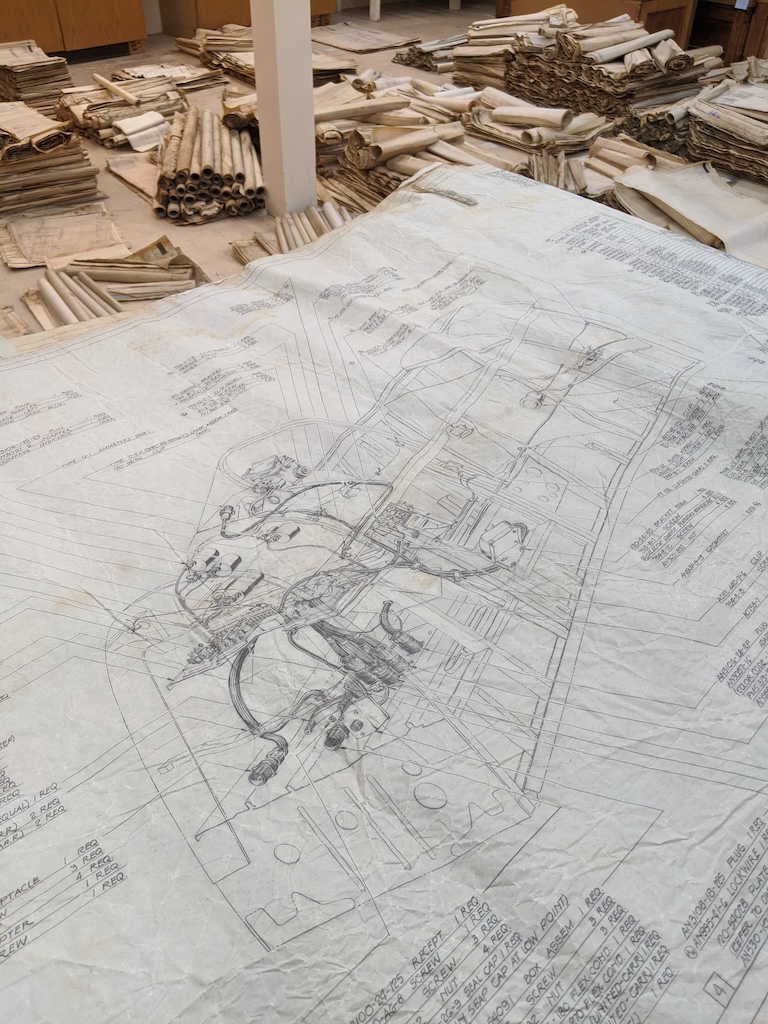

The team designed a system of a lattice framework made of wire that the archival tubes are placed in to create a wall full of suspended tubes, then the drawings are placed in those archival tubes. The drawings currently remain in the same staging area that they were when the collection arrived, but there are plans to create a more permanent and climate-controlled area for different types of storage depending on the side of the drawing. Most are “cut size” drawings which are standard sizes ranging from 8 1/2 x 11 inches up to around 32 x 46 inches. These drawings will eventually all go into flat file cabinets, while anything larger will stay rolled and go into tubes to prevent exposing the drawings to light for too long.

What It’s All About

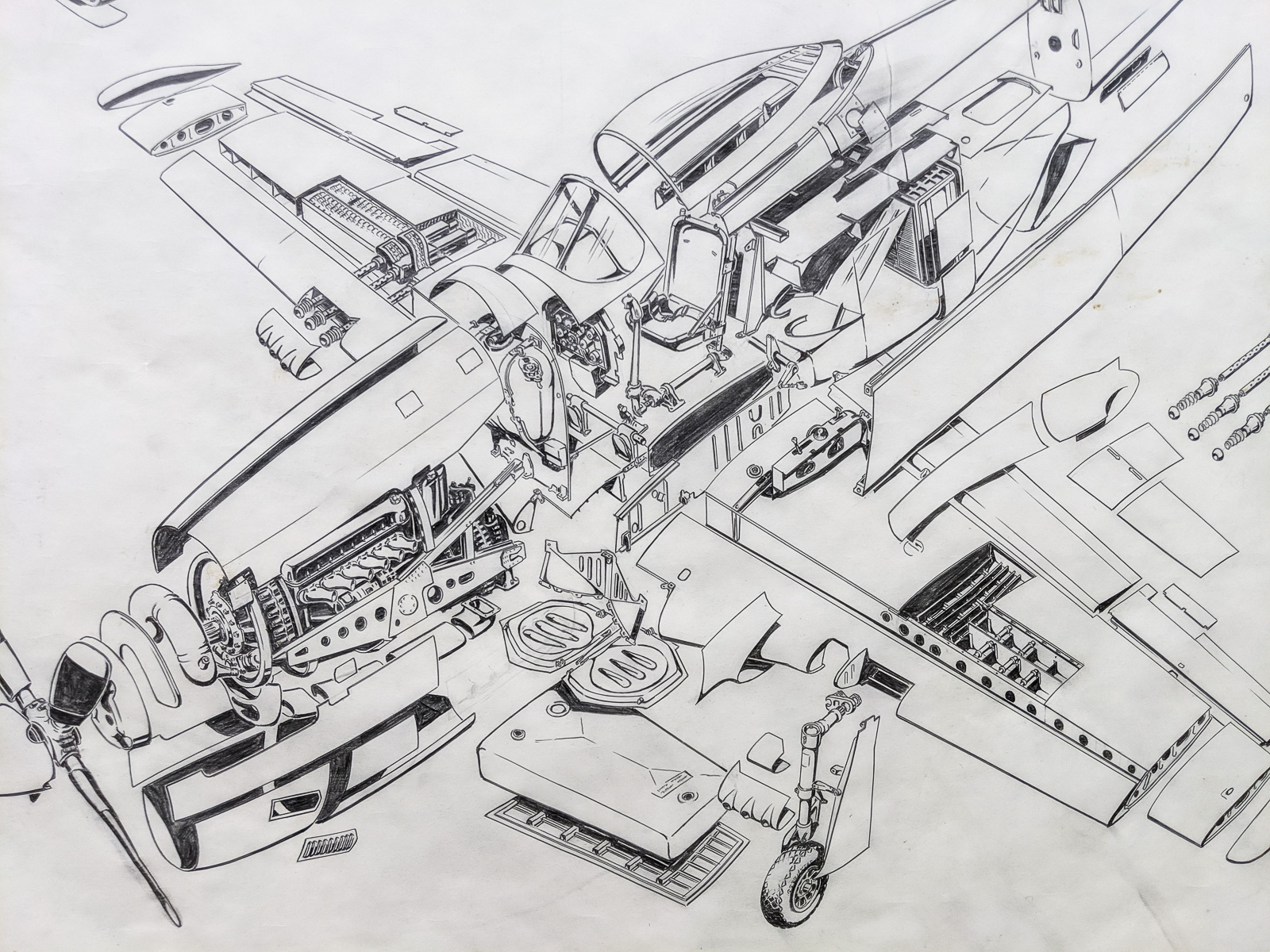

There are many fascinating and fun parts of the project for Aube, and it is always an unexpected treat to come across something that is extra remarkable. “By definition, people don’t look at a fuel selector valve or some of these smaller standard parts and be like, oh, wow, that’s so amazing,” she says. “But sometimes you’ll pull out a drawing of a really simple part or assembly and for whatever reason, that draftsman decided to spend a little bit of extra time and do shading and draw it in perspective. I’ve had moments where I flipped to a drawing and even I have to do a double take and say, ‘Somebody didn’t draw that, that’s a photo.’ I’m always amazed…it’s such a chaotic and crazy time in our nation’s history when it was all hands on deck and everybody was doing something really to help the war effort that someone decided to take a little extra time and make a drawing a work of art in sense…For me, I consider every drawing to be a work of art.”

There is still much to learn from the collection, which will continue to be revealed as more drawings are cataloged. The ongoing project is far from being finished, yet people are already visiting the collection for help in their warbird projects, including a B-25 history project out of Kansas City rebuilding an eight-gun nose from the B-25 which is not well documented in the original B-25 microfilm. “We found a whole stack of drawings of experimental stuff and unreleased drawings in the collection that were able to help them with their work,” says Aube. “And that’s really what it’s all about.”

Visit the EAA Aviation Museum to see the drafting exhibit through September 2025.

Related Articles

Emma Quedzuweit is a historial researcher and graduate school student originally from California, but travels extensively for work and study. She is the former Assitant Editor at AOPA Pilot magazine and currently freelance writes along with personal projects invovled in the search for missing in action aviators from World War I and II. She is a Private Pilot with Single Engine Land and Sea ratings and tailwheel endorsement and is part-owner of a 1946 Piper J-3 Cub. Her favorite aviation experience was earning a checkout in a Fairchild PT-19.

“Tame rudder pedal used in the T-6, the T-28, B-51, and B-25.” or should it be, “Same rudder pedal used in the T-6, the T-28, P-51, and B-25.”

If the pedal ain’t broke, don’t fix it!!

Really good article.Never thought about this.These draftsmen are artisthis

Perhaps an effort to publish the drawings would work. The General Land Office of the State of Texas makes a good bit of money selling old maps. They could be contacted and visited to get an idea what it takes. I would gleefully paper a wall with such “art”.