From the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution‘s newsletter

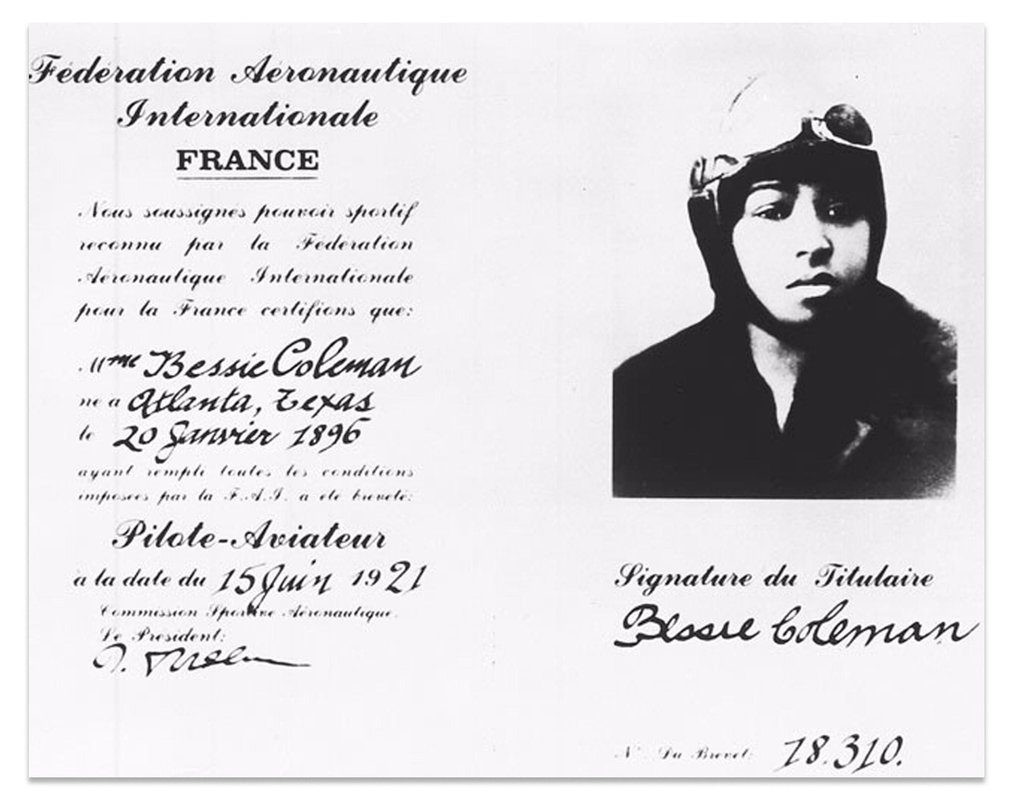

One hundred years ago on June 15, 1921, Bessie Coleman became the first African American woman and the first woman of Native American descent to earn a pilot’s license. The license was issued by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), the aviation licensing body of Europe — Bessie moved to France to learn to fly because the skies weren’t open to her as a Black woman in the United States.

Bessie Coleman, byname of Elizabeth Coleman, (born January 26, 1892, Atlanta, Texas, U.S.—died April 30, 1926, Jacksonville, Florida), American aviator and a star of early aviation exhibitions and air shows. One of 13 children, Coleman grew up in Waxahatchie, Texas, where her mathematical aptitude freed her from working in the cotton fields. She attended college in Langston, Oklahoma, briefly, before moving to Chicago, where she worked as a manicurist and restaurant manager and became interested in the then new profession of aviation.

Discrimination thwarted Coleman’s attempts to enter aviation schools in the United States. Undaunted, she learned French and in 1920 was accepted at the Caudron Brothers School of Aviation in Le Crotoy, France. Black philanthropists Robert Abbott, founder of the Chicago Defender, and Jesse Binga, a banker, assisted with her tuition. On June 15, 1921, she became the first American woman to obtain an international pilot’s license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. In further training in France, she specialized in stunt flying and parachuting; her exploits were captured on newsreel films. She returned to the United States, where racial and gender biases precluded her becoming a commercial pilot. Stunt flying, or barnstorming, was her only career option.

Coleman staged the first public flight by an African American woman in America on Labor Day, September 3, 1922. She became a popular flier at aerial shows, though she refused to perform before segregated audiences in the South. Speaking at schools and churches, she encouraged blacks’ interest in aviation. She also raised money to found a school to train black aviators. Before she could found her school, however, during a rehearsal for an aerial show, the plane carrying Coleman spun out of control, catapulting her 2,000 feet to her death.

Bessie Coleman’s personal drive and accomplishments are truly inspiring and her remarkable journey reflects the racist and sexist struggles many faced across the nation, and worldwide, in the 1920s — both in the air and on the ground.

Bessie’s story is one that deserves to be widely known and celebrated.

Learn more about Bessie Coleman’s journey to the skies and the challenges she had to overcome to achieve her dreams in curator Dorothy Cochrane’s new blog Celebrating the Centennial of Bessie Coleman as the First Licensed African American Woman Pilot.

Coleman’s life and legacy aren’t just limited to aviation. In the air and on the ground, she made history, changed history, and witnessed history. Get a glimpse at the barrier breaking, fearless, multifaceted woman she was in Bessie Coleman: Five Stories You May Not Know. Discover more resources about Bessie Coleman and the legacy she left behind on the Museum’s Bessie Coleman webpage.