These days, it is often hard to find intact surviving examples of WWII Japanese aircraft, even in Japan itself. Those aircraft that were not shot down, destroyed on the ground in bombing raids, or lost in accidents were, by and large, scrapped by U.S. occupational forces in the immediate aftermath of the war. Yet at the Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots (Chiran Tokko Heiwa Kaikan) in Kagoshima Prefecture, Kyushu, sits the sole remaining example of one of the most advanced fighters ever flown by the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force during WWII: the Nakajima Ki-84 Hayate (Gale), better known to its American foes by the Allied reporting name “Frank”. The story of how this Frank became the last example of its kind, however, is full of twists and turns that make for a most incredible story.

At the start of the Pacific War, the latest fighters in the Japanese Army Air Service (IJAAS) were the Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa (Peregrine Falcon), which the Allies would call the “Oscar”, and the Nakajima Ki-44 Shoki (Devil Queller), Allied reporting name “Tojo”. Yet even then, the Imperial Japanese Army realized that as the war dragged on, a new fighter would be needed. Nakajima was tasked with developing a new fighter with a more powerful engine, heavier armament, and longer range. The result was the Nakajima Ki-84, which was first flown in the spring of 1943 and was placed into frontline combat by June 1944.

The Hayate was powered by the Nakajima Homare, an air-cooled, twin-row 18-cylinder engine that produced up to 2,000 hp. It was armed with two Ho-103 12.7mm synchronized machine guns in the nose and two Ho-5 20mm cannons in the wings, and was also fitted with self-sealing fuel tanks in a trend of the mid- to late-war period of getting rid of more vulnerable unarmored fuel tanks. Japanese pilots loved the speed and maneuverability of the new design, and when American pilots faced the aircraft that they called the Frank, it earned their grudging respect, and when paired with some of Japan’s dwindling reserves of combat veteran pilots, it was a formidable opponent.

The Ki-84 was flown in the war-torn skies of China, Burma, the Philippines, and the Japanese Home Islands, fighting against everything from American fighters such as the Mustang, Thunderbolt, Hellcat, and Corsair, to the Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers that pummeled the Japanese Home Islands from bases seized from the Japanese themselves in the Mariana Islands. However, despite the improved performance of the Hayates and other late-war fighters of both the Japanese Army and Navy, the Americans pushed the Japanese off Iwo Jima and Okinawa, their B-29s set Japanese cities ablaze in firebombing campaigns, and both land-based and carrier-based fighters roamed the skies of the Home Islands. Yet until the emperor called for the Japanese people to surrender, the Ki-84 pilots and ground crews fought on until the bitter end.

The combat career of the Hayate did not end with the Second World War. In the Dutch East Indies, Indonesian guerrillas sought to reclaim their independence, rather than let the Dutch colonial forces reclaim the East Indies. The Indonesians equipped themselves with leftover Japanese equipment, including Ki-84s, and used them during the Indonesian National Rebellion (1945-1949). In China, the civil war between the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek and the Communists under Mao Zedong, which was interrupted by the Japanese invasion in 1937, soon resumed in 1945. During the war, both the Nationalists and the Communists used captured Japanese equipment, and both had Ki-84s in their respective air forces, though the Nationalists increasingly used more and more Western fighters exported to them to fight the Communists. After forcing the Nationalists to withdraw to Taiwan, the People’s Liberation Army Air Force continued using Ki-84s and other Japanese aircraft until they were replaced by fighters exported from the Soviet Union.

After the war, some Ki-84s were shipped to the United States for technical evaluation, mainly at the Middletown Air Depot (now Harrisburg International Airport) in Pennsylvania, it was determined that with a top speed of 427 mph at 23,000 feet and a rate of climb at 4,300 ft/min from sea level, the Ki-84 Hayate was equal in performance to many contemporary American piston engine aircraft. Much of these performance figures, though, were made after the Americans had fueled the fighters with 140-octane avgas, while the Japanese were often limited by their own fuel refining capabilities to 87-octane avgas.

Among the Ki-84s brought to the United States was the aircraft now displayed in Chiran. Built in late 1944 as a Ki-84-I Ko variant at the Nakajima Aircraft factory in Ōta, Gunma prefecture. It was soon accepted into the IJAAS as serial number 1446 and was sent to the 11th Hiko Sentai (11th Flying Regiment), 2nd Chutai, which had been transferred from Taiwan to the Philippines to fend off the American amphibious landings. The aircraft of the 11th Sentai were flown to their new base of operations at Clark Field on the Philippine Island of Luzon, about 40 miles northwest of Manila, which had been bombed and later captured by the Japanese during their invasion of the Philippines from December 1941 to May 1942. During the Philippine campaign, the 11th Sentai flew against American aircraft, but the Americans’ numerical superiority in aircraft, ships, tanks, and logistics, combined with local support from Filipino guerrilla fighters, forced the Japanese to retreat and pull their remaining forces back, including the 11th Sentai. During the evacuation, several Japanese aircraft, including Ki-84-I Ko s/n 1446, which had received damage in combat, were abandoned at Clark Field, which was recaptured by the Americans by January 31, 1945.

When the Americans discovered s/n 1446, the aircraft had a red lightning bolt with white borders painted on its rudder and vertical stabilizer. On the lower part of the rudder, the unit number 46 was painted in white, leading to the aircraft being referred to as White 46 in later publications. The aircraft also had a missing portion of the leading edge of its left wing. With the area around Clark Field back in American hands, intelligence analysts from the Technical Air Intelligence Unit for the South West Pacific Area (TAIU-SWPA) arrived to evaluate the abandoned Japanese aircraft, such as Mitsubishi J2M Raiden “Jack” naval interceptors, Yokosuka D4Y Suisei (Comet) “Judy” dive bombers, Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” twin engine bombers, and two Nakajima Ki-84 “Franks”. It was then decided that the captured aircraft that could be made airworthy were to be flight tested at Clark Field under close observation with American test pilots.

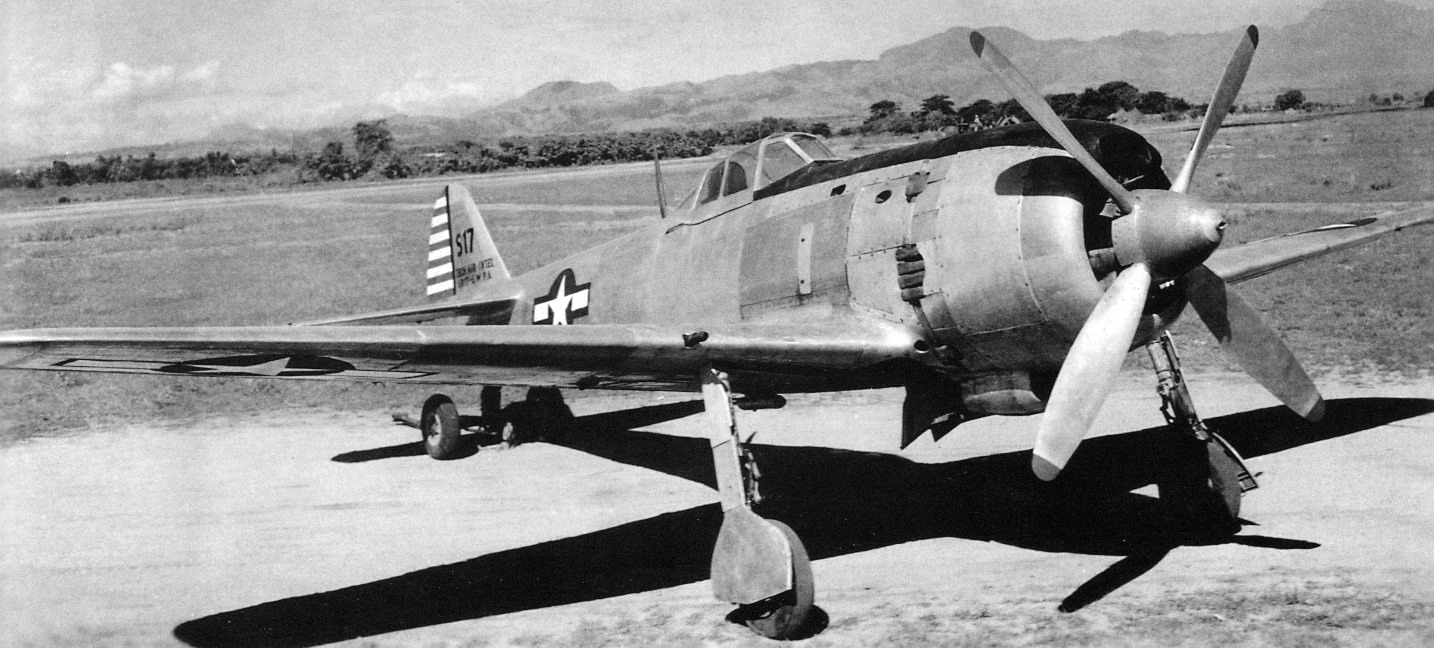

The two Franks were given the TAIU identifying codes S10 and S17, with s/n 1446 becoming S17. Like the other captured aircraft at Clark Field, the two Ki-84s had their Japanese markings stripped, being flown in a bare metal finish with US Army Air Force markings and black paint on the upper nose surfaces to reduce glare from the sun. To further identify the planes as being flown by Americans, the rudders were painted with the US red and white stripe pattern similar to the prewar tail markings of USAAC aircraft. In addition to being flown for performance evaluation, the two Ki-84s were flown against Grumman F6F Hellcats, Republic P-47D Thunderbolts, North American P-51D Mustangs, and even Supermarine Seafires of the Royal Navy’s British Pacific Fleet (BPF).

It was these tests that gave American pilots their first impression of the Ki-84, and tactics developed to counteract the Ki-84 were developed for use in aerial combat. After the surrender of Japan, USAAF intelligence units now had unfettered access to thousands of Japanese aircraft and parts on the Home Islands. In addition to the new aircraft captured on the Home Islands, though, it was decided to send some of the surviving aircraft still at Clark Field from the Philippines to the United States for further evaluations against new American fighters rolling off the production lines. Among these was Ki-84 S17, which was shipped to the USA aboard the first American escort carrier USS Long Island (CVE-1).

Eventually, the aircraft was among dozens of allied and Axis aircraft selected for preservation in a future aviation museum and was sent into storage at a former Douglas C-54 assembly plant at Orchard Place Airport (now Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport) in the Chicago suburb of Park Ridge. It was decided that the vast majority of the aircraft at Park Ridge would be transferred by the newly independent US Air Force to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air Museum (now the National Air and Space Museum). However, with the outbreak of the Korean War, the Smithsonian was evicted from the Park Ridge facility in 1952 by the USAF and was forced to move its collection to the Silver Hill Storage Facility in Suitland, Maryland. However, some of the Japanese aircraft were declared to be in excess of the collection, and some of these intact aircraft were either scrapped or reduced into smaller portions.

Upon hearing of this development, a young aircraft collector from Claremont, California, named Edward T. Maloney, enquired to see if any of the Japanese fighters declared to be in excess could be sold off. He was told that he could pick one of two airplanes: the Ki-84 “Frank”, or a Kawasaki Ki-45 Toryu (“Dragonslayer”), a twin-engine heavy fighter with the Allied reporting name “Nick”. Maloney chose the Frank, and in September 1952, the aircraft arrived in Claremont, where Maloney placed it in storage alongside a growing collection of surplus WWII airplanes that he hoped would be the centerpiece of a new museum, where he would be able to have these aircraft in airworthy condition.

While Maloney was trying to open his Air Museum, the first of its kind west of the Mississippi River, Maloney attracted the attention of movie producers from MGM Studios. They were making a film adaptation of the novel Never So Few, written by Tom T. Chamales, a former captain in the special operations unit Merrill’s Marauders, which waged a guerrilla war against the Japanese in occupied Burma (now Myanmar). The film, whose cast included the likes of Frank Sinatra, Gina Lollobrigida, and Steve McQueen, would have a Japanese-held airfield, and knowing Maloney had collected some Japanese aircraft, asked him to provide some examples. Maloney agreed, and the Ki-84 Hayate and Mitsubishi A6M5 Zero construction number 5357, tail code 61-120 (whose story we have covered HERE), were sent to the production set, with the Hayate being repainted in the markings of the 52nd Sentai, and its Nakajima Homare radial engine was fired up for taxiing in front of the cameras in a short scene alongside the parked Zero.

After the production of Never So Few concluded, Hayate s/n 1446 and Zero 61-120 were transported back to Claremont, where on January 12, 1957, Maloney opened The Air Museum at a former lumberyard on Foothill Blvd (Route 66), where the Ki-84 was one of ten airplanes on display. Over the six years, Maloney and his volunteers found more airplanes to add to the collection, but it was clear that the Claremont facility was running out of space, and the nascent museum began an effort to move to nearby Ontario Airport, where Maloney’s dream of a museum with flyable aircraft became closer to becoming a reality.

In March 1963, just as The Air Museum was planning to open the new museum in Ontario, the museum got a call from a TV studio asking them to provide a Japanese fighter and a US Navy fighter for a production project. At this time, the museum’s Board Chairman was none other than WWII flying ace and Korean War pilot Colonel Walker “Bud” Mahurin, who now worked for Garrett AiResearch, an aerospace company at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). Using his position in the company, Mahurin had the Hayate dismantled and trucked to AiResearch, where it was restored to airworthiness.

There was much excitement about the project at LAX, as it was only 18 years since WWII ended, and many pilots and engineers there, like Mahurin, had served during the war, and it was the first time a Japanese aircraft had been restored by private hands to flight status. The aircraft was also registered with the FAA as N3385G.

Work proceeded quickly, as the repairs to the aircraft, including the replacement of sheet metal patches over bullet holes, was finished in May and on June 25, 1963, Bud Mahurin took the Ki-84 for its first test flight. The results proved satisfactory, and in July, the aircraft made its public debut at the Air Force Reserve Air Fair held at Orange County Airport (now John Wayne Airport) in Santa Ana and was the star attraction of the show. By this point, the new location at Ontario Airport had been opened, and for the rest of the 1960s, the world’s last Ki-84 Hayate, which was also the last Japanese aircraft of WWII in airworthy condition, made its home at Ontario Airport, and continued to fly in local airshows. One of these shows was recorded in this film posted by the San Diego Air and Space Museum Archives’ YouTube channel: F-0261 California Air Museum (Planes of Fame, Chino) Video, P-51.

However, like many museums, The Air Museum in Ontario did not have infinite financial resources, especially when the museum began moving its static collection to Buena Park in 1970 and would later move the entire collection to Chino Airport in 1973. Ed Maloney had previously sold off or traded some of his airplanes for new examples for his collection and to gain proceeds to maintain the museum, and by 1973, Maloney sold the Ki-84, N3385G, to museum pilot Don Lykins. However, Lykins could not afford to maintain the aircraft, but there was a buyer who was interested in purchasing the aircraft to fly in the land of its birth.

In 1973, Lykins sold the Ki-84 to Morinao Gokan, president of the Japanese Owner Pilots’ Association and a WWII veteran pilot. He flew the aircraft at the 1973 Japan International Aerospace Show, held at Japan Air Self Defense Force Iruma Air Base from October 5-11. This marked the first time that a WWII Japanese fighter had flown in Japanese skies since 1945, and incredibly, the footage of this flight demonstration has also been preserved, namely through this video posted on YouTube: Ki-84 Hayate Rare Color-Footage: 1973 Japan International Aerospace Show. In addition to Gokan flying the aircraft, Don Lykins and Ed Maloney came to Japan, with Lykins flying the Hayate at Iruma, while Maloney watched. During that air show, even as they prepared to leave the Hayate in Japan, they met with the president of Mitsubishi Aircraft, who upon learning that the museum in California had an A6M Zero, asked Lykins and Maloney if they could restore it to flying condition, prompting the restoration of Zero 61-120, which remains airworthy to this day.

Unfortunately, this would be Ki-84 s/n 1446’s last public flight. The expense in maintaining a one-of-a-kind fighter aircraft that had not been in production for thirty years at that point was just as challenging in Japan as in America. During the 1970s, the aircraft was displayed at the factory of the company that succeeded Nakajima, Fuji Heavy Industries (later Subaru), in Utsonomiya, where it was exposed to the elements. Following the death of Morinao Gokan, the Hayate was then transported to the Arashiyama Museum near Kyoto, where it was displayed alongside a Mitsubishi A6M7 Model 62 Zero, construction number 82729, tail code 210-118 B (now displayed at the Kure Maritime Museum (also known as the Yamato Museum)). In 1991, the privately-operated museum near Kyoto closed, and the aircraft was placed into storage for four years.

In 1995, the final twist in Hayate 1446’s long journey unfolded. The aircraft was made a centerpiece of the Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots, in Kagoshima Prefecture on the home island of Kyushu. Chiran had been the home of an airfield in which many young pilots who joined the Special Attack Units (or kamikazes) had departed on their final, fateful sorties during the Battle of Okinawa. Since the museum was constructed in 1985, it houses artifacts commemorating the kamikaze pilots, including many of their poignant final letters written to their friends and families just prior to their missions. While the Nakajima Ki-84 Hayate was not used for kamikaze missions, as it was still one of the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service’s most capable fighters in 1945, Hayate squadrons operating from the Home Islands would escort the kamikaze pilots to prevent American fighters from shooting them down before reaching the American taskforces on their one-way missions.

Since its arrival at the Chiran Peace Museum, the world’s last surviving Nakajima Ki-84 Hayate, having flown on both sides of the Pacific, rests in a place of honor, with its exterior having been restored and the aircraft placed completely indoors. Though some may lament the fact that the aircraft no longer flies, the fact that it remains in existence today is a testament to the foresight of both American and Japanese enthusiasts, from Ed Maloney to Morinao Gokan in preserving this Hayate for future generations, and it is indeed fitting that this aircraft now resides in the land of its birth.