by Gregory Alegi

How does one spell “one hundred” in the air? Well, if you are the Italian Air Force, you fly six Lockheed F-35As to form the “1”, eight Eurofighter Typhoons to create the “0”, and eight Alenia Aermacchi T-346s to shape the remaining “0” – all in trailing formation over Rome – from the Colosseum to Piazza del Popolo. Today’s flypast will help to celebrate the Italian Air Force’s centenary as an independent air arm. The service came into being on March 28, 1923, five years after the Royal Air Force but almost a quarter-century before the U.S. Air Force.

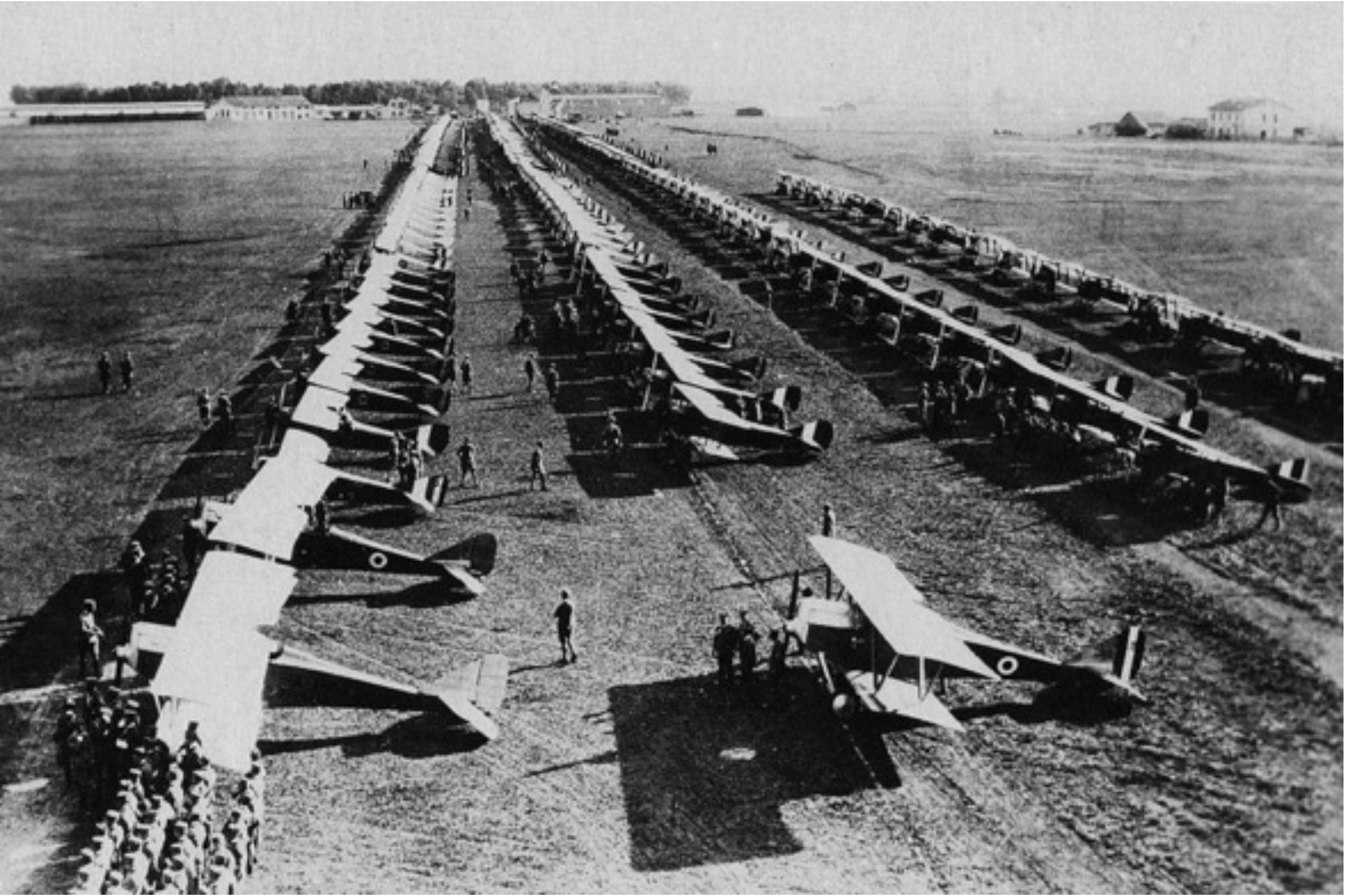

Italy already sported a significant tradition for military flying at that time. In fact, it was an Italian named Captain Carlo M. Piazza who, on October 23rd, 1911, performed the world’s first operational sortie, flying a reconnaissance mission in a fragile Blériot XI over the Oasis of Zanzur (south west of Tripoli, Libya) during the Turkish-Italian war. Four years later, Italy entered World War One on the Allied (Entente) side, fielding separate Army and Naval air services which enjoyed near-continuous superiority over their Austria-Hungarian opposition in both quality and quantity, a situation perhaps best symbolized by the daring raid of August 9th, 1918 which saw nine Ansaldo SVA biplanes fly over Vienna, dropping leaflets inciting the Austrians to surrender. In parallel, the country trained some 10,000 pilots (including several hundred Americans) while building over 12,000 aircraft, including three-engined, Caproni Ca.3 bombers.

However, the Austro-Hungarian surrender on November 4th, 1918 raised the issue of what Italy’s military should do next with it’s aviation component. Amidst the general demobilization of the day, modernists called for the establishment of aviation as a third service, on equal terms with the nation’s Army and Navy, and possibly unique in its ability to strike at the heart of enemy territory and morale. This vision, enshrined by the theorist Giulio Douhet in his 1921 book Il dominio dell’aria (The Command of the Air), ran contrary to the traditionalist military hierarchy, which viewed aircraft as little more than useful observation platforms; Army Generals and Naval Admirals were horrified by the prospect of diverting scarce, postwar funding to such an enterprise. Eventually two alternatives emerged: a British-style Air Ministry, with control over all air assets, or a less ambitious structure to procure aircraft and train pilots for existing surface forces.

When Benito Mussolini became Italy’s leader on October 28th, 1922, many ardent aviators hoped he would follow the first option, but his weak coalition government could ill-afford an early fight with the military, then closely connected to king Victor Emmanuel III and the House of Savoy. After twice attempting to put Douhet in charge of the nascent air service, Mussolini bowed to Army pressure and hammered out the compromise Royal Decree 645. While Article 1 proclaimed the creation of «the Regia Aeronautica [Royal Air Force], which comprises all military air forces of the Kingdom and its Colonies», Article 8 stipulated that air units «assigned to Italy’s Regia Esercito [Royal Army] and Regia Marina [Royal Navy] and Ministry of Colonies for actual exercises and actual use» would come under their command and would be based in agreement with them. In short, aviators got their own uniforms and ranks but control remained largely in other hands. The new service would report to a Commissariat for Aeronautics, at a lower level of importance than the Ministries of War and Navy – at least until 1925, when it was upgraded to Ministerial status. In an attempt to nip criticism in the bud, the post went to Mussolini himself.

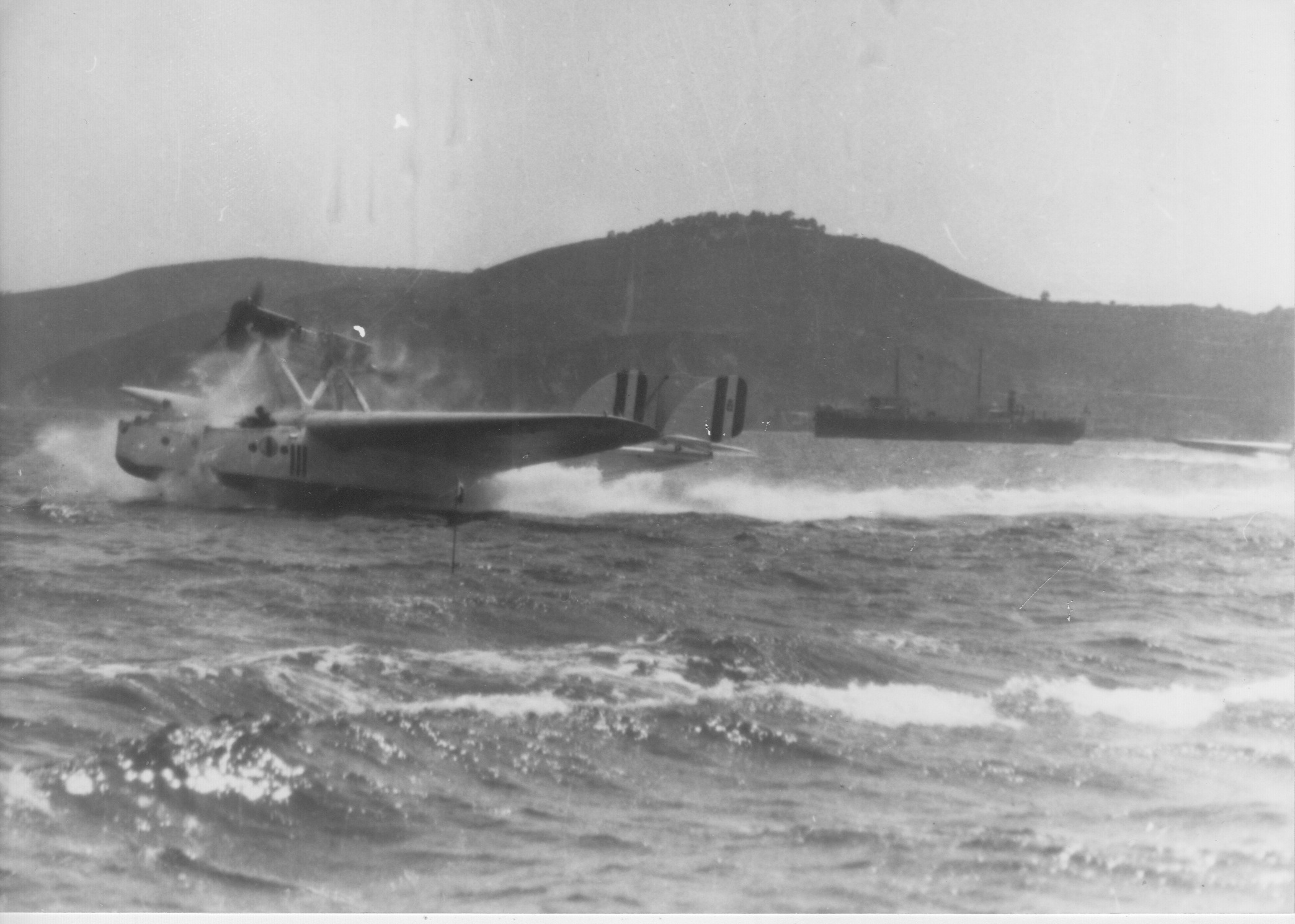

Much remained to do, of course. The young service was small, understaffed, underfinanced and possessed leadership problems. These issues were gradually solved following the appointment of General Bonzani as Deputy Commissioner (1924-26) and then Italo Balbo as Under Secretary. While Bonzani brought much needed order and discipline to the service, it was Balbo who provided a sense of mission and purpose. Despite receiving less than one-sixth of the overall defense budget, in his seven years as Undersecretary (1926-29), Balbo pushed to move the Regia Aeronautica away from individual talent to the teamwork and professionalism embodied by the four massed flights to Spain (1928), USSR (1929). Brazil (1930-31) and eventually Chicago and New York (1933). By the time the young and energetic Balbo returned from the USA, Mussolini now regarded him as a competitor to his own leadership. In short order, Mussolini promoted Balbo to become governor of Libya, appointed himself Air Minister and promoted Chief of Staff Giuseppe Valle to Undersecretary.

Sadly, in 1935, Mussolini plunged Italy into a decade of war which would end in crushing defeat in 1945. In October 3rd of that year, Mussolini launched the invasion of Ethiopia, a meticulously prepared operation in which air power provided ground support, reconnaissance and even the airlift which allowed Italy’s Army to attack through the desert from Somalia. With the fall of Addis Ababa, on May 5th, 1936, Mussolini proclaimed victory and empire; in reality, however, counter-insurgency operations continued for three more years. In July 1936, Italy became involved in the Spanish Civil War, a totally unplanned event which absorbed enormous domestic resources. Again, the Aeronautica performed well and dominated the skies where they flew. While the two wars proved the service capable of winning limited conflicts, World War Two placed it in a far more difficult test. The rough numerical parity they enjoyed with the RAF in 1939 soon slipped away but, more importantly, Italy’s aircraft industry proved unable to deliver competitive types in adequate numbers. By early 1943, Italy had lost North Africa and the nation’s cities were under near-constant attack. In July, the back-to-back invasion of Sicily and first bomber offensive against Rome caused Fascism to fall. Formal surrender followed on September 8th, splitting the country in two, with the North under Mussolini and the South under the King, each with its stub air force. The Aeronautica Repubblicana fielded two fighter wings against Allied bombers, while the Regia Aeronautica operated in support of Italian Army units stranded in the Balkans.

The 1947 peace treaty and, more importantly, 1949 NATO membership allowed the Aeronautica Militare (Italian Air Force) – as the service became renamed following Italy’s move from a Kingdom to a Republic – to rebuild itself with US aircraft and training. This made the 1950s a period of growth and expansion for the Aeronautica Militare, epitomized by the annual rotation of increasingly ambitious acrobatic teams, which led to the creation of the Frecce Tricolori in 1961. Two years later, the Aeronautica received its first Lockheed F-104G Starfighter, a type which soon became ubiquitous. The next leaps forward saw the introduction of the swing-wing Panavia Tornado (see our 40th Anniversary STORY) and the AMX fighter bomber, a joint development between Italy and Brazil.

After more than 45 years of peacetime operation, the Aeronautic returned to combat in 1991, with Operation Locusta, the codename for Italy’s participation in Operation Desert Storm. This action highlighted the quality of Italian aircrews, but also revealed the many improvements needed to operate in a truly integrated fashion with US and NATO forces. Soon, As a result, the Aeronautica launched a comprehensive overhaul of both its structure and equipment suite, a plan which it has followed with remarkable commitment for more than three decades while helping quell conflicts in the Balkans, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya.

As it turns 100, the Aeronautica Militare is a modern, balanced, and effective air force. Its mix of F-35s, Eurofighters, G-550 CAEW early warning aircraft, KC-767A tankers, and MQ-9A drones is presently unrivaled amongst western European nations. Meanwhile the service is gearing up to confront challenges in the emerging cyber and space domains. So today’s flypast and air base open days are here to not only celebrate the past, but to also herald the future.

The Aeronautica Militare, on the occasion of its centenary, offers a calendar articulating the program of multi-disciplinary initiatives which will take place throughout 2023. For more information, please click HERE.

You can follow the Aeronautica Militare on the following social media platforms:

YouTube / aeronauticamilita…

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AeronauticaM…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/italianairforce

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/aeronautica…

TikTok: https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMN8mhpry/

Telegram: https://t.me/AeronauticaMilitareOfficial

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/company/aero…

Related Articles

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.