Last September, the Royal Aircraft Museum of Western Canada in Winnipeg welcomed the return of an aircraft that has returned from an extended stay in Europe. This aircraft, a Junkers F 13, is a very rare example of the first all metal transport airplane, which has had quite the journey that spans nearly a century and two continents before it’s return back to Winnipeg.

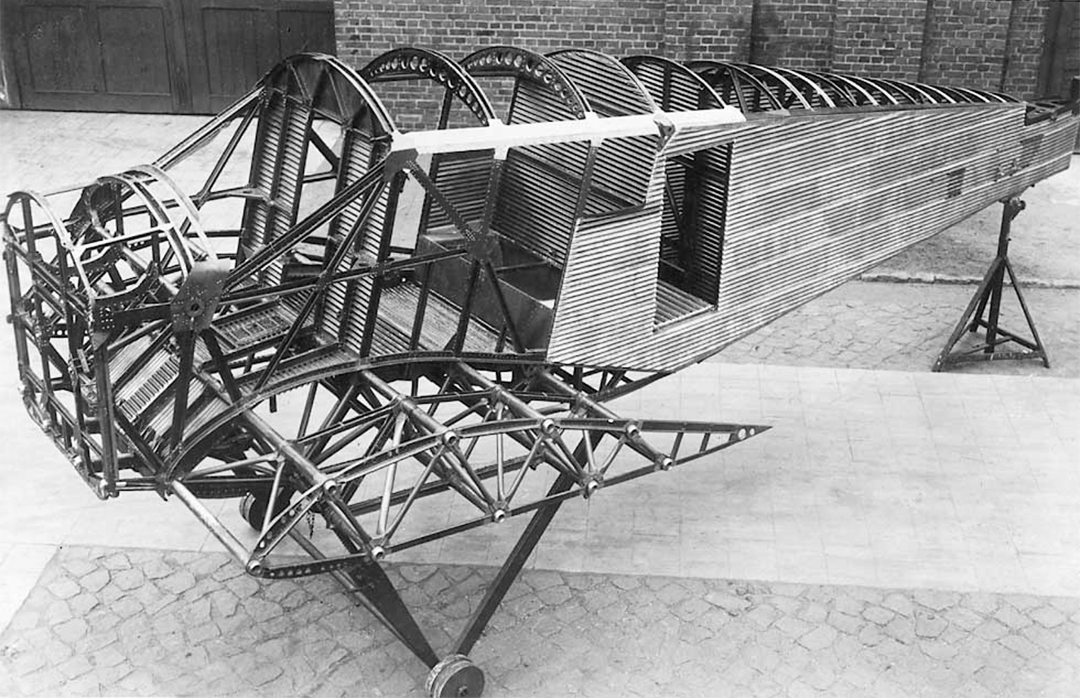

The Junkers F 13 was the product of the Junkers Flugzeug- und Motorenwerke AG (Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works) of Dessau, Germany. During WWI, the company had produced the first all-metal airplane, the J 1, and a few subsequent designs such as the J 4 (designated the J.I by the German Luftstreitkräfte (Air Service) and the J 9 (military designation D.I) became the first all metal airplanes to see combat and enter mass production. With Germany’s defeat in 1918, the Armistice ordered the transfer of all military aircraft to Allied authorities and the Treaty of Versailles prohibited Germany from ever fielding an air force. In the face of this, Dr. Hugo Junkers and his chief aircraft designer, Otto Reuter, set to work on a concept for a single engine civilian aircraft drawn up in broad strokes during the war. Originally called the J 13, the result of their labor would become known as the Junkers F 13, the world’s first all-metal transport plane to enter mass production and worldwide service, which first flew on June 25, 1919.

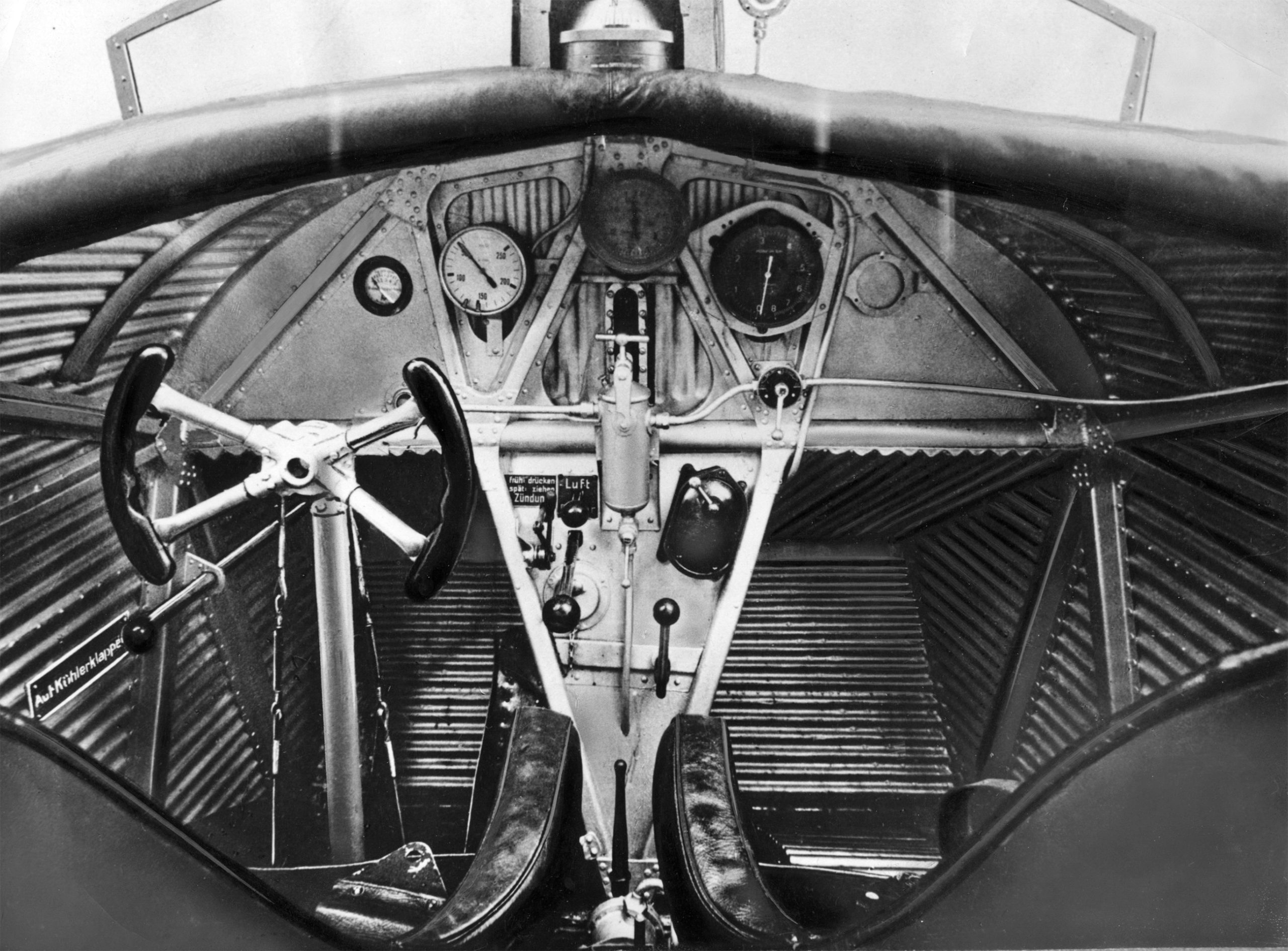

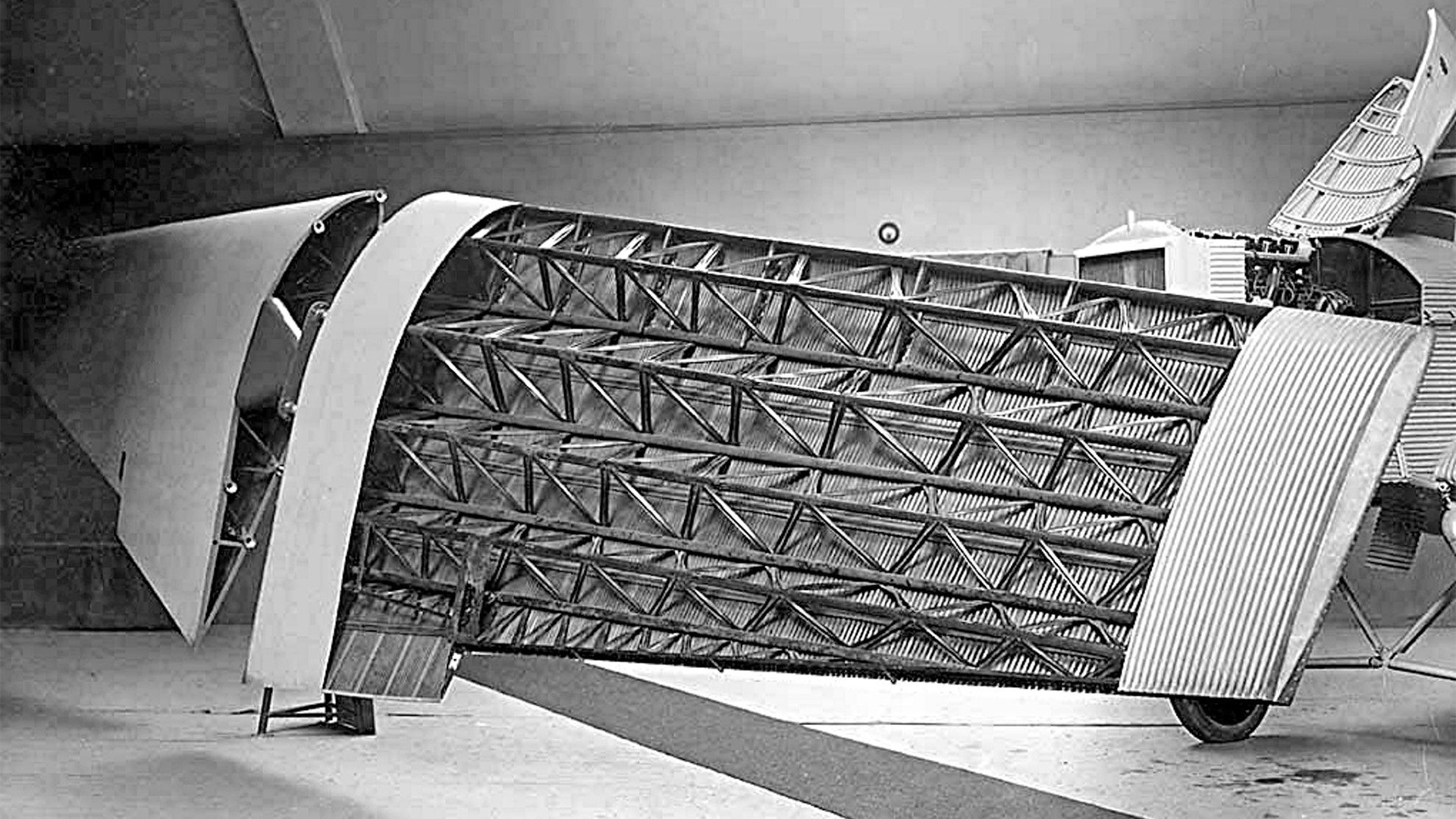

Compared to the contemporary wood and canvas biplanes that dominated the aviation market at the time, the Junkers F 13 was a night and day difference. Its skin was made of corrugated duralumin alloy riveted over spars and struts in the wings and fuselage. The aircraft would carry a crew of two pilots in a semi-open cockpit and four passengers in an enclosed cabin. The F 13 was also very adaptable, being able to swap its fixed landing gear for floats or skis depending on operating conditions, and many were powered by Junkers’ own L5 six-cylinder inline engine, along with a variety of additional powerplants. The F 13 was also produced outside Germany in Sweden, the Soviet Union, and even the United States, and was flown as far as Afghanistan, Bolivia, South Africa, and Hungary among many other nations around the world, representing an estimated 40 percent of global air traffic in 1925. Later, the type would provide a basis for other Junkers single engine transports, such as the W 33 and W 34. Over 300 F 13s were produced during the 1920s and 1930s, but today only five examples have been preserved around the world, including the subject of this article.

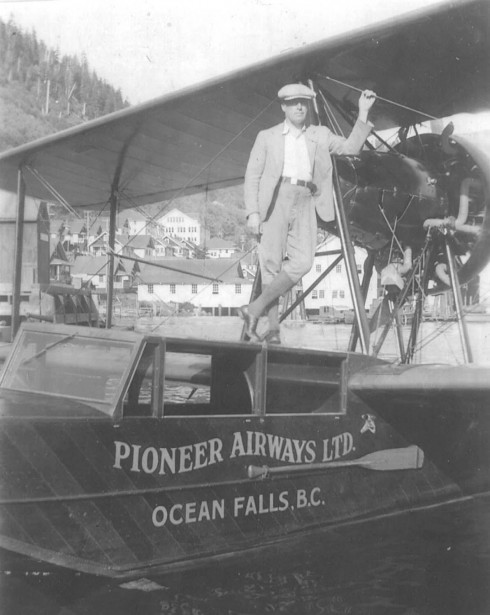

In 1930, the Junkers plant in Dessau produced F 13 construction number 2050. It was given the name Königsgeier (King Vulture) but would find itself being exported to Vancouver, British Columbia, where it would be added to the Canadian civil register on May 27, 1930, bearing the registration code CF-ALX. The aircraft was owned by the Air Land-Manufacturing Company in Vancouver, which also acquired another Junkers F 13, which was built in Germany in 1923 as serial number 663 and was registered as CF-AMX after previously flying in Germany and the United States as D-288 and NC87 respectively. Together, these aircraft would be used to support mining operations in the vast expanse of the Canadian bush country, using pontoon floats to land on rivers and lakes to access remote areas of the country.

CF-ALX was reassembled in a hangar at the Wells Air Harbour on Lulu Island, Vancouver, with the assembly being overseen by British-born flight engineer Ted Cressy. Cressy later accompanied the German pilot Wilhelm (who Anglicized his name to William) Joerss on its first flight in Canada. Along with Joerss and Cressy, the Air Land-Manufacturing Company would hire pilots Edward J.A. “Paddy” Burke and F. Maurice MacGregor and engineer Emil Kading to maintain the two F 13s.

On June 5th, 1930, Joerss flew CF-ALX to Prince George, which sits at the confluence of the Fraser and Nechako rivers. After circling a couple of times over the city, he landed at Tabor Lake, then called Six-Mile Lake. Fourteen days later, on June 19, an official dedication ceremony to mark the air transit route from Vancouver to Prince George, where Prince George’s mayor, A.M. Patterson, and Joerss spoke to a crowd of 500 attendees before Norine Patterson, the mayor’s youngest daughter, christened CF-ALX as City of Prince George, breaking a bottle of wine against the nose of the Junkers. Joerss then took the mayor and his daughters Norine and Georgina and the city clerk, V.R. Clerihue and his wife, for a flight in the City of Prince George. After returning from this short flight, Joerss took several other dignitaries, including R.A. Renwick, editor of the Prince George Citizen for flights around the city.

Joerss then offered sightseeing flights of the area for $25 for up to five passengers at a time, with flights to “local points” offered at $1.50 a mile for up to five passengers – with a $50 extra charge if an overnight stop was required

For the next three years, CF-ALX made repeated visits in and out of the wilderness of British Columbia and the Yukon Territory. Every time the City of Prince George flew into Prince George, crowds of people gathered into their cars to see it land and take off again from Six-Mile Lake. Oftentimes, the City of Prince George flew up to four passengers or a load of cargo and was able to swap between fixed wheels or pontoon floats. In May 1933, CF-ALX was sold to Colonel Victor Spencer, a businessman and rancher from Vancouver who had also served as a Lt. Col. in the Canadian Army during WWI. Colonel Spencer was also the son of department store founder David Spencer and served as the director of the Pioneer Gold Mine and Pacific Nickel Mines. As such, the City of Prince George was to continue to support mining operations in Canada. But soon after Colonel Spencer’s purchase of CF-ALX/City of Prince George, its career was to come to a sudden end.

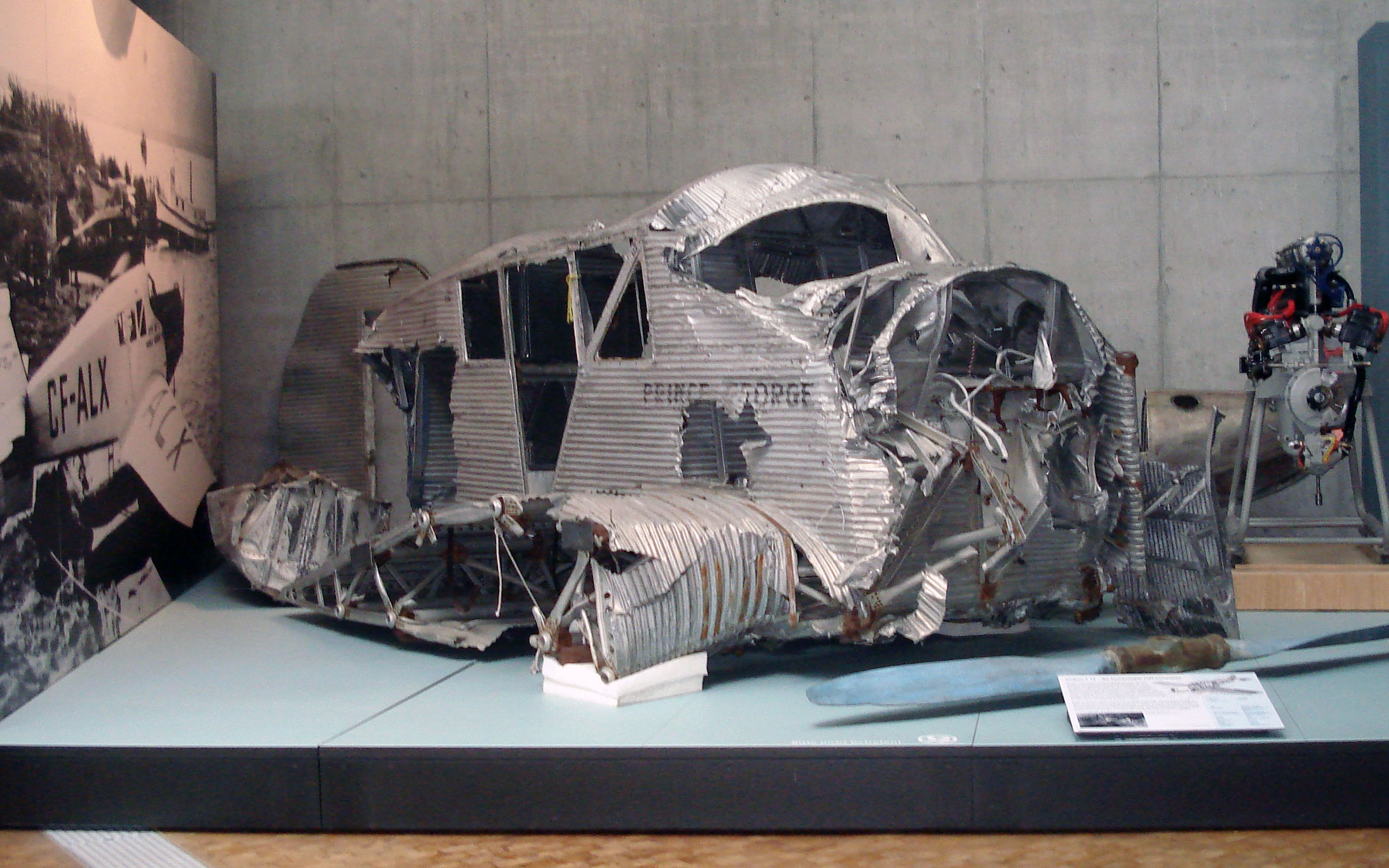

On July 23, 1933, pilot William McCluskey and flight engineer Fred Staines flew the City of Prince George to McConnell Lake, some 100 miles from the nearest settlement of Takla Landing, in northern British Columbia, and which sits inside a cup-like depression. There they picked up two prospectors, Gordy McLennan and Hugh McMillan, and McCluskey began to apply full power for takeoff from the lake. Soon after pulling out of the water, though, the City of Prince George hit a downdraft which kept it from ascending above the approaching tree line. The Prince George’s Junkers L5 engine roared at full throttle as it careened into the treetops, but the plane fell further into the trees. While fighting the downdraft, McCluskey spotted a small clearing by a creek bed ahead of them, enough room to make a forced landing. As McCluskey throttled down to make the landing, the left wing struck a spruce tree with a diameter of 2.5 feet, breaking the wing off but also uprooting the tree itself. The right wing, meanwhile, struck another tree, and the starboard pontoon was ripped from the airplane and thrown clear of it. The Junkers fell into a field of boulders, with one barely missing Fred Staines in the right side of the cockpit. The tail was also torn from the airplane during the crash, but remarkably, all four men escaped serious injuries themselves. The City of Prince George had proved, even in a crash, the F 13’s ruggedness. But surviving the crash was one thing. Finding someone to rescue them was another matter altogether.

Word of the crash reached Takla Lake through a miner who had hiked five days from the crash site to Takla, and soon, a rescue party was assembled to retrieve the survivors. When the searchers found the survivors, it was decided to salvage as much of the aircraft as possible and leave the rest behind, with this effort being led by one C.S. Cameron. Cameron and Staines spent a day making a wider clearing to remove the parts. In this effort they were assisted by miners who journeyed from some of the nearby digging sites. Chief among the components to be recovered would be the engine. In pouring rain, with access only to the tools that were at hand, Staines began carefully dismantling the L5 engine. Cameron would recall later, “The tree which had spiked that wing remained fast and several of us wrestled with it in vain. During an interval’s rest, a thick-set miner, out hunting, approached with gun in hand. He simply exclaimed ‘Howdy,’ surveyed the scene, dropped his gun, put his shoulder under the troublesome tree and walked away with it.”

The next day, Staines continued dismantling the engine, in spite of pouring rain. Having completed the task, the parts were loaded into parcels, with the heaviest components being the crankcase and the crankshaft. They had to be carried by hand across creeks and through the bush to a waiting Junkers W 34 transport, registered as CF-ABK, and flown by WWI veteran pilot Norman “Norm” Forester. After taking several trips in and out of the British Columbian bush, the remainder of the City of Prince George was left to the elements where it fell for the next 47 years.

In 1981, Keith Olson and Gordon Emberley, two of the founders of the Western Canada Aviation Museum (now the Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada), sought to recover the old Junkers F 13, which was now considered one of only five examples of the type in the world, with the others known to be in France, Germany, Sweden, and Hungary. In the summer of that year, a team from the WCAM recovered the wreckage of the City of Prince George, but given the condition it was found to be in 47 years after its write-off accident, it was kept in storage, un-restored by the museum. In 2005, the WCAM made a mutually beneficial arrangement with the Deutsches Technikmuseum in Berlin (DTMB), Germany. In exchange for loaning the F 13 back to Berlin, the DTMB would place the aircraft on display and eventually find the resources to restore it for the WCAM. This would result in the City of Prince George returning to Germany in 2006 for the first time in over 70 years, but this time, it would cross the Atlantic not by ship but by a Lufthansa cargo plane.

For several years, the F 13 was displayed in an unrestored state at the Deutsches Technikmuseum in Berlin, with the wall behind it plastered with a historic image of the intact aircraft in Canada during the 1930s, its name still clearly visible on the fuselage. Later, the aircraft was sent to be restored in Hungary, along with the remains of another Junkers from the WCAM, Junkers W 34 CF-AQV, serial number 2710, which crashed on September 1, 1939, which had also been recovered by the WCAM and had been placed on long term loan to the DTMB.

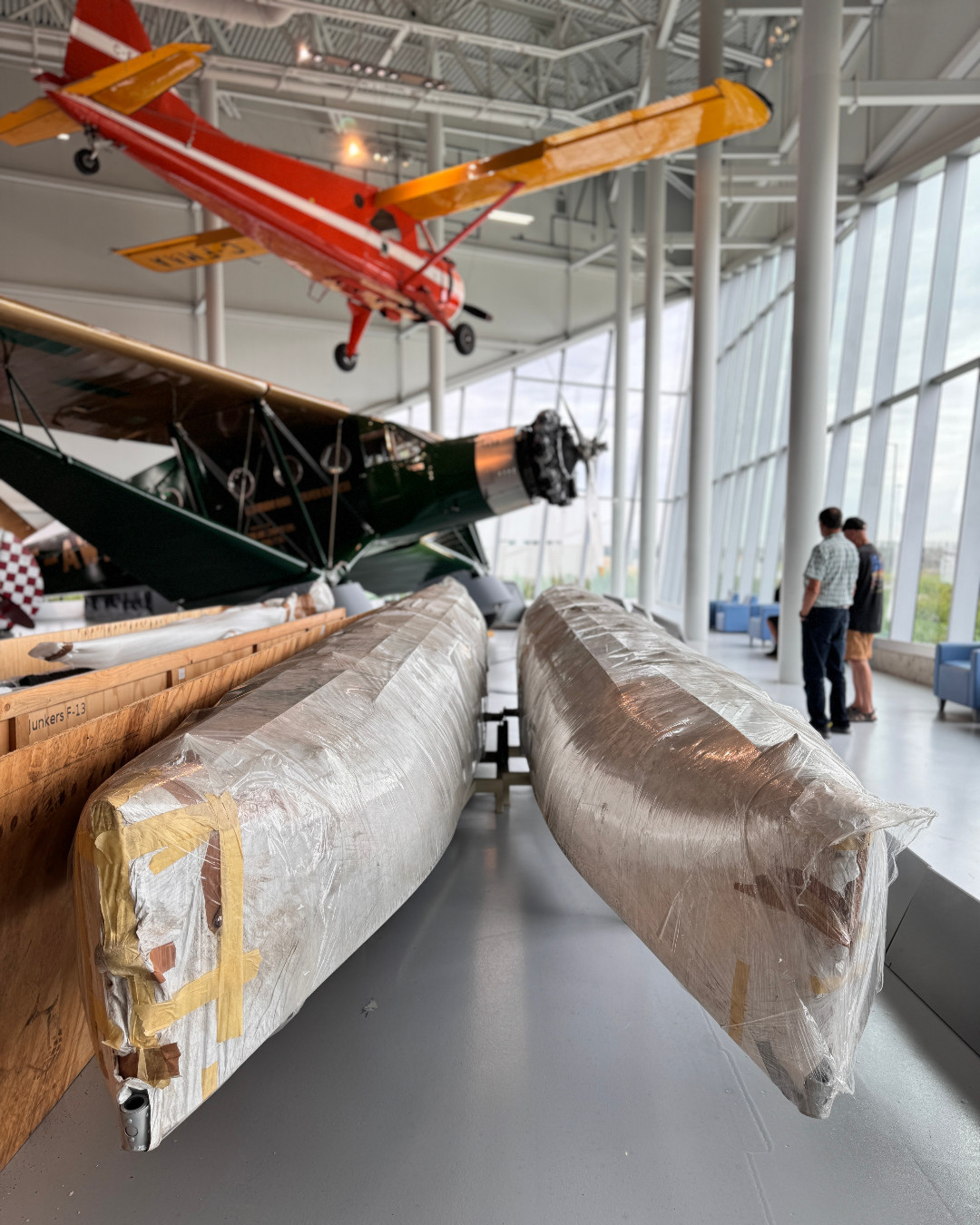

In September 2024, the King Vulture/City of Prince George was returned to the Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada. Among those who welcomed it back were Keith Olsen and Gordon Emberley, no doubt thinking back to when they first saw its wreckage at McConnell Lake.

With the City of Prince George back in Winnipeg, the Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada will reassemble the aircraft on the museum floor and will have it displayed in its configuration as a floatplane.

In the meantime, the restoration team has also been focused on other projects including the final reassembly of the museum’s recently restored Canadair Sabre Mk.6 RCAF s/n 1815, which has also been brought to the museum’s display floor. The RAMWC will reassemble the aircraft in due time, however, as the only surviving Junkers F 13 displayed outside Europe. For more information, visit Home – Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.

This artifact is a true Canadian heritage story and we should all be grateful