Thus, only a small number of Peashooters were ever produced, and today, only two survive. Adam will take us through their amazing history, and you’ll learn about how the Museum’s Ed Maloney found and saved this flying wonder.

By Adam Estes

Whenever visitors to the Planes of Fame Air Museum walk out of the gift shop and into the Edward T. Maloney Hangar to start their journey through the museum, they are greeted by one of its most prized aircraft, the Boeing P-26A Peashooter. Built as an example of the first all-metal monoplane fighter in service with the U.S. Army Air Corps, it is now one of only two originals left, and the only one that can still fly. It also contains a fascinating story of an interwar relic being thrust into Cold War intrigue.

On June 16, 1934, two years after the first flight of the Model 248 prototype, a freshly manufactured P-26A, construction number 1899, was officially accepted into the US Army Air Corps as serial number 33-123 at Boeing Field in Seattle, Washington. Ten days later, it was assigned to the 1st Pursuit Group, at Selfridge Field, near Mount Clemens, Michigan. In September of that year, the 1st Pursuit Group was ordered to deploy to Kelly Field near San Antonio, Texas, to partake in winter war maneuvers. During the series of flights from Michigan to Texas, 33-123 was assigned to the Operations Officer of the 27th Pursuit Squadron, Lieutenant Thayer Olds. On September 21, Olds was landing at one of the refueling stops when the aircraft nosed over due to a faulty brake. Fortunately, Olds was uninjured, and the damage to the aircraft was limited to the lower cowling, propeller, and left wingtip. The subsequent accident report concluded that due to a failure in the assembly of the right brake, the brake locked on landing, causing the aircraft to nose over. Lt. Olds’ record was cleared of any error on his part. The report was signed by the commanding officer of the 1st Pursuit Group, Colonel Frank Maxwell Andrews, later to be the namesake of Joint Base Andrews near Washington, D.C.

While the report was being filed, the damaged fighter was sent to be repaired at the Fairfield Aviation General Supply Depot at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, before returning to service with the 27th Pursuit Squadron at Selfridge. However, by 1936 the Peashooter was no longer the most advanced fighter in the Army Air Corps, as new fighters complete with enclosed cockpits and retractable landing gear such as the Seversky P-35, which would replace the P-26s in service with the 1st PG, entered USAAC service. Following this the 1st Pursuit Group transferred much of their P-26s, including 33-123, to the 20th Pursuit Group at Barksdale Field in Louisiana, which was now the last Pursuit Group in the continental U.S. to fly the Peashooter.

By the end of the 1930s, many of the surviving Peashooters still in service with the USAAC were now serving on airfields outside the continental United States, such as those in the 4th Composite Group at Clark Field and Nichols Field in the Philippines or with the 18th Pursuit Group at Wheeler Field, Hawaii. But 33-123 would be sent to another destination. In August 1938, 33-123 was overhauled at the San Antonio Air Depot before being transferred the following month to the air depot at Rockwell Field in San Diego, which was later integrated with the pre-existing Naval Air Station at North Island. From there, 33-123 was disassembled and loaded into an Army transport ship bound for the Panama Canal Zone, an unincorporated territory that straddled five miles on either side of the canal along the width of the Isthmus of Panama, which included several US military outposts. Among these was Albrook Field, which now served as the main airport for Panama City.

Upon arriving at Albrook in October of 1938, 33-123 was assigned to the 16th Pursuit Group. Pilots assigned to the Canal Zone typically had little to do in the pre-war years besides flying and going to the bar in the officer’s club, and Panama was also where much of the Air Corps’ second-line planes went to serve out the remainder of their useful years of service. By 1940, however, more modern fighters such as the Curtiss P-36 began making their way to Panama, and the remaining Peashooters were transferred once more to the Air Force Division of the Army’s Panama Canal Department, essentially being restricted to reserve duties through the designations RP-26A and eventually ZP-26A.

[wbn_ads_google_three]

With the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the subsequent declarations of war upon the United States by Germany and Italy on December 11, the US feared that both the Germans and the Japanese could threaten the safety of the Panama Canal with their respective submarine fleets. By then, only seven P-26s were left in operational service in Panama, but they were nevertheless armed, sometimes with their small bombs, and patrolled the Pacific and the Caribbean coasts looking for German and Japanese ships and submarines, but none of the plans made by the Axis powers to attack the canal were ever carried out. With the arrival of new aircraft in Panama, the P-26s would eventually be drummed out of what was now the US Army Air Force, but rather than having the planes returned to the United States, the country of Guatemala expressed a keen interest in purchasing the aircraft.

Having declared war against the Axis powers themselves in December of 1941, the Guatemalan Army Air Corps sought to find some new aircraft to replace its aging fleet of 1930s aircraft. Its fighter arm, for example, was composed of Ryan ST-A trainers with wing-mounted machine guns. While the Peashooters were no longer the most advanced fighters at this point, they were still dedicated fighter aircraft. However, although the American personnel in Panama were willing to transfer the Peashooters, Congress blocked the transfer, as it had barred the transfer of lethal weapons to all Latin American countries (except Mexico and Brazil). However, there was no provision made to the transfer of training aircraft, and thus the Boeing P-26s were redesignated as PT-26s trainers which, even though a variant of the Fairchild PT-19 was already designated the PT-26, was enough for the Peashooters to be legally transferred to Guatemala.

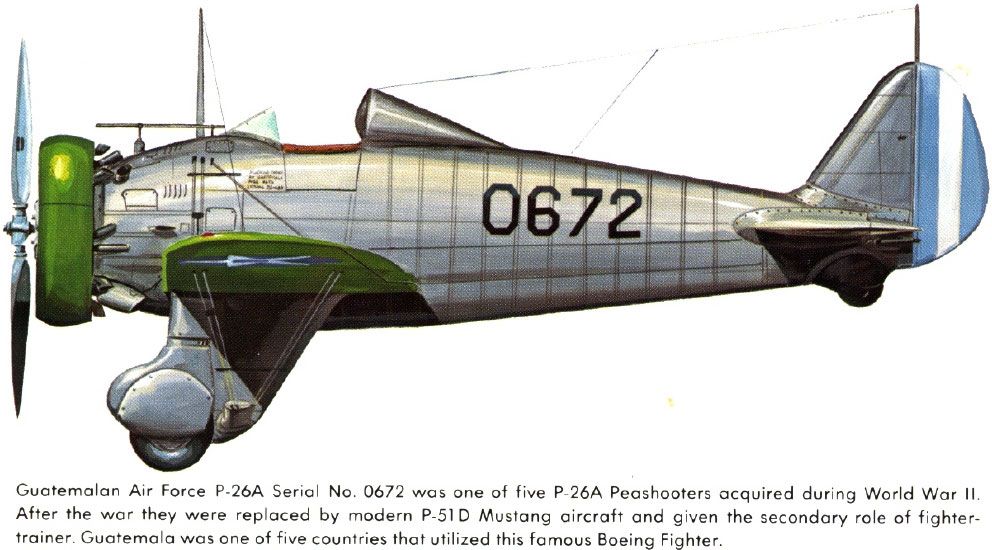

With all of the aircraft re-serialed by the Guatemalans, 33-123 became serial number 43. It would be painted in an overall olive drab scheme but with the figure of a helmeted soldier on the rear fuselage. Eventually, this fuselage art was painted over, and the fuselage was later stripped of paint entirely, save for the green cowling ring and the new serial number, 0672, being applied to both sides of the fuselage.

[wbn_ads_google_four]

But like their American counterparts, the Guatemalan pilots had to learn the hard way that the Peashooter was sometimes difficult for a new pilot to land due to its high landing speeds. Being some of the fastest aircraft in the Guatemalan Air Force, they were often prominently displayed at ceremonies and aerial demonstrations at La Aurora Airport, near the capital of Guatemala City. The Peashooters were also used as single-seat trainers alongside armed AT-6 Texans, but lack of spare parts and proper maintenance also limited their effectiveness.

By 1954 only three P-26s, including s/n 43, remained in airworthy condition, maintained and flown by three Captains in the Guatemalan Air Force (Rene Sarmiento, José Luis Lemus Ramis, and Pedro Granados), but in Guatemala City, the trajectory of the country was about to be forever altered. In 1952, the democratically elected president of Guatemala, Jacobo Arbenz Guzman, enacted an Agrarian Reform Law that sought to distribute uncultivated land from the United Fruit Company to Guatemalan farmers. However, the reform-minded Arbenz had made enemies among the conservative establishment in Guatemala, and what’s more, the United Fruit Company (now called Chiquita) had friends in Washington, namely two brothers; Allen and John Foster Dulles, who were the Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the Secretary of State respectively, and had been appointed by newly-elected president Dwight D. Eisenhower who sought to enhance America’s already-firm anti-communist foreign policy, though the outgoing President Harry Truman had already begun preparations to install a new leader more friendly to U.S. interests. The U.S. found their man in the form of an exiled right-wing military officer, Carlos Castillo Armas. With a guarantee of support from the U.S. government, Armas returned to Guatemala with a counter-revolutionary army, and with American mercenary pilots flying unmarked surplus aircraft, such as P-38 Lightnings and P-47 Thunderbolts. After just nine days, from July 18th to 27th, 1954, Arbenz was forced to resign the presidency and flee into exile while Armas took power as a U.S.-backed military dictator until his assassination in 1957. The resulting political turmoil would see Guatemala erupt into civil war in 1960, and the fighting would not cease until 1996. But during those nine days in 1954, Captains Sarmiento, Lemus Ramis, and Granados remained loyal to the government under Arbenz but only had the three remaining Peashooters at their disposal against the American fighters. They decided they would patrol the skies of Guatemala City in an attempt to intercept the rebel aircraft, which often approached the capital city from the south. However, these aircraft flew twice as fast as the aging Peashooters and often changed their approach vectors. Despite their lack of success, there is something to be said about the character of the three captains who were willing to risk their lives in the defense of their country. With the Armas regime now firmly in place, Washington had secured a firm anti-communist partner in Guatemala at the cost of Guatemalan democracy. By 1956, there were but two Peashooters left, with s/n 43 being re-serialized as 0672, and with orders of surplus P-51 Mustangs coming in from the United States, the last two surviving Peashooters were decommissioned in 1957, the same year in which Carlos Castillo Armas was assassinated by a member of his presidential guard, and the growing unrest in Guatemala would eventually lead to a brutal civil war that raged from 1960 to 1996, and while the country may have a large export market, the legacy of 1954 and the civil war continue to cast a shadow over the country’s modern history.

As the last Peashooters soldiered on in Guatemala, a young collector named Edward Maloney began looking for a P-26 to display and eventually fly as part of his collection. As a young boy growing up during the 1930s, Maloney had watched dozens of Peashooters of the 17th Pursuit Group during their regular flying operations from March Field, and now that he was beginning to collect vintage aircraft, he sought to find an example for his growing collection. His search for a Peashooter began in 1951, and he chased every lead he could find. He investigated reports of P-26s left in the Philippines or Hawaii, but to no success, and things weren’t better in the continental United States. He had heard that one aircraft, P-26C 33-197 remained at Chanute Air Force Base in Illinois, but by the time he was able to reach out to them, he was disappointed to learn that it had already been scrapped in 1949. But in 1955, he learned from a friend of his of the existence of the P-26s in Guatemala and sought to find a way to bring at least one of them home.

Having appealed to the Guatemalan Air Force, Maloney was able to secure one of the now-decommissioned Peashooters, serial number 0672/33-123 to return it to the United States. Around this time, the Smithsonian National Air Museum (now the National Air and Space Museum) had also learned of the last Peashooters in Guatemala and purchased the other remaining Peashooter, 0816 (formerly USAAF serial 33-135), which was loaded into the cargo hold of a Fairchild C-119 Flying Boxcar and flown back to the USA. This aircraft was later loaned to and restored by the National Museum of the USAF at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio where it was displayed until 1975. From there, 33-135 moved to the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. and is now suspended from the ceiling of the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, near Dulles International Airport in Chantilly, Virginia, named for none other than Secretary of State John Foster Dulles.

[wbn_ads_google_four]

Returning to 33-123’s story, once the necessary paperwork and customs clearance was completed, the Peashooter was disassembled and trucked to the Pacific coast of Guatemala in July of 1957, where it was placed on a barge to be loaded into the hold of a cargo ship bound for the Port of Los Angeles at San Pedro. After six uneventful days at sea, the ship arrived in San Pedro, where Maloney and a group of volunteers supervised the unloading of the priceless aircraft and were met with the rich aroma of millions of coffee beans inside the hold around the Peashooter! From there, the Peashooter was trucked to a former lumber yard that was the site of what Maloney then called The Air Museum, located on Route 66 in Claremont, where it was displayed for two years in its Guatemalan colors.

In 1959, the museum received a request for the aircraft to be present at an airshow in Long Beach. The aircraft was trucked to the airport and was repainted in the colors of the 34th Pursuit Squadron (The Thunderbirds), which was attached to the 17th Pursuit Group at March Field in Riverside. The next year, the aircraft would be displayed at an airshow at March Air Force Base in Riverside. There, it paled in comparison to the massive B-52 Stratofortress and F-105 Thunderchiefs that represented the modern air force of that time, just thirty years removed from the era of the Peashooter. When it wasn’t on display at airshows, 33-123 was back at the museum in Claremont.

In the spring of 1962, WW2/Korean War ace Walker “Bud” Mahurin, who was also a pilot for The Air Museum, spearheaded efforts to restore the aircraft to airworthiness in time for the Air Force’s Gunnery Meet and Air Power Demonstration at Indian Springs Air Force Auxiliary Field (now Creech Air Force Base), 45 miles northwest of Las Vegas, Nevada. Since Mahurin worked for Autonetics, a division of North American Aviation, he was able to arrange for the aircraft to be brought to Autonetics’ Flight Test Facility at Los Angeles International Airport for a complete overhaul to be restored to flight, which was carried out by a volunteer team. The team was also able to secure a sponsorship from Pratt & Whitney to fund the rebuild of the R-1340 radial engine, which was done by Aviation Power Supply in Burbank, while the volunteer team scrounged to find as many replacement parts as they could bring to LAX.

Having been registered with the FAA as NX3378G, the aircraft was assembled together in preparation for static engine runs and flight testing, but the deadline for the airshow at Indian Springs was fast approaching, and under a typical series of tests, the Peashooter would be too late to the show. In light of this, Mahurin took the Peashooter on its first flight with the museum on September 16, 1962, with Mahurin at the controls. Because of the approaching deadline for the event, Mahurin also took advantage of the test flight to fly the aircraft to Las Vegas McCarran Airport! The next day, Mahurin then made the short flight to Indian Springs in time for the air show on the 18th and returned to California without incident.

Following this event, the Peashooter was flown at numerous airshows across southern California and displayed at each of the proceeding locations of the museum following the move from Claremont, from Ontario to Buena Park, and finally settling in Chino. The Peashooter was often flown alongside the museum’s Boeing P-12E and the Seversky AT-12 Guardsman to demonstrate the interwar aircraft of the US Army Air Corps. But by the early 1980s, the Peashooter was largely relegated to being placed on static display due to its rarity, along with the P-12. But by 2006, the museum decided to restore the Peashooter to the air once again for that year’s airshow, which had the theme of “Fighter Command”. The airframe and engine were in good shape, and the plane went through a thorough check, with items being inspected and replaced where necessary, and the aircraft was given a new paint scheme, this time representing the 95th Pursuit Squadron (The Kicking Mules), which had also flown the P-26 out of March Field as part of the 17th Pursuit Group. This is the current scheme in which the aircraft appears today.

With the Peashooter making a successful test flight on May 9, 2006, with Steve Hinton at the controls, the aircraft became a big hit during the airshow from May 20-21, and the Peashooter would continue to be the star of the annual airshow at Chino, the occasional Living History Day on the first Saturday of a particular month, and often makes the short hop to March Air Reserve Base for the airshows there.

Perhaps the most exciting adventure that the museum’s Peashooter has embarked on in recent years has been the time when the museum had the plane shipped across the Atlantic in a shipping container to Duxford, England, for the 2014 Flying Legends airshow. For many of the show’s attendees, this was the first time they were able to see a Boeing P-26 Peashooter in person, and it also marked the first time that a P-26 had been brought to Europe since the shipment of an export version, the Model 281, that was brought to Spain in 1935 and fought briefly during that nation’s civil war before it was shot down in October of 1936 over the outskirts of Madrid. Having arrived by shipping container at The Fighter Collection in Duxford, a crew from the Planes of Fame, led by Steve Hinton, was on hand to oversee the reassembly of the little fighter. While high cross winds grounded the Peashooter for all but one day of flying, it made its presence known, and the flight by Steve Hinton was widely considered to be a highlight of the show. Soon after the event ended, it was packaged once again and returned safely to Chino.

While the Planes of Fame and the Smithsonian may have the only two original Boeing P-26s in the world, several full-scale reproductions and replicas are on display elsewhere. Two static reproductions built by museum restoration specialists can be found at the San Diego Air and Space Museum and the National Museum of the USAF, while an airworthy reproduction is maintained by the Military Aviation Museum in Virginia Beach, Virginia, and two partially-completed reproductions, having been started by Tim and Gayla O’Connor of Golden Age Aeroplane Works in Brownstown, Indiana, have now been moved to the Legend Flyers workshop in Everett, Washington, with the intent of fulfilling the original of flying both reproductions upon their completion. Finally, a static replica is also displayed in the Filipino city of Balanga, the capital of Bataan Province. It is displayed inside the provincial capitol building and is marked as an aircraft of the Philippine Army Air Corps, whose pilots bravely flew against more advanced Japanese aircraft and pilots during the invasion of the Philippines in December 1941.

For more information on the fascinating story of the Peashooters in Guatemala, author Mario Overall has written an excellent article for the Latin American Aviation Historical Society (LAAHS) which can be read here.

To help keep the Boeing P-26 Peashooter and other aircraft at Planes of Fame flying, visit https://planesoffame.org/. For more information about the Hangar Talk and Flying Demo of the Boeing P-26A Peashooter, click HERE.

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.

Excellent article. Wonderful history.

history well recorded