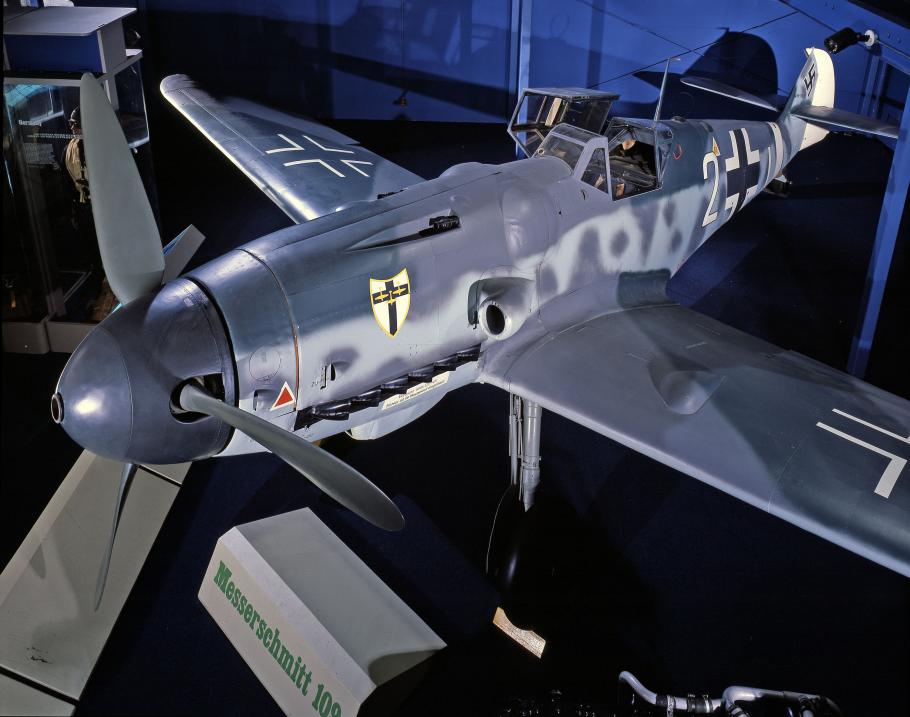

Last year, we reported on the incredible discovery of the identity behind the National Air and Space Museum’s Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6/R3, which was being restored for display in the museum’s upcoming Jay I. Kislak WWII in the Air gallery, to be inside the museum’s National Mall location in downtown Washington, D.C. Now, we can state that for the first time since 1944, the aircraft assigned the German Werknummer 160756 now wears the historic scheme of Jagdgeschwader 4 (JG 4), which this aircraft was assigned to during WWII. As noted in our original story on this aircraft, it has been traced by archivists and aviation historians to have been built in late 1943 at the Messerschmitt AG factory in Regensburg, Germany, as part of a production batch assigned the serial numbers (Werknummers) 160745 through 160770, with corresponding fuselage codes from KT+LA to KT+LZ applied at the factory. As such, aircraft 160756 was assigned the fuselage code KT+LL when delivered to the Luftwaffe.

The aircraft was classified as a G-6/R3, a long-range reconnaissance variant of the fighter with the capacity to carry two wing-mounted 300-liter drop tanks. The aircraft also had attachment points for a pilot-operated sand filter over its oil cooler to operate in desert environments. Upon being accepted into the Luftwaffe, the aircraft was delivered to Jagdgeschwader 4 (JG 4), which had been transferred from Romanian to northern Italy. JG 4 painted 160756 in a green and dark tan camouflage pattern and received the fuselage code Yellow 4.

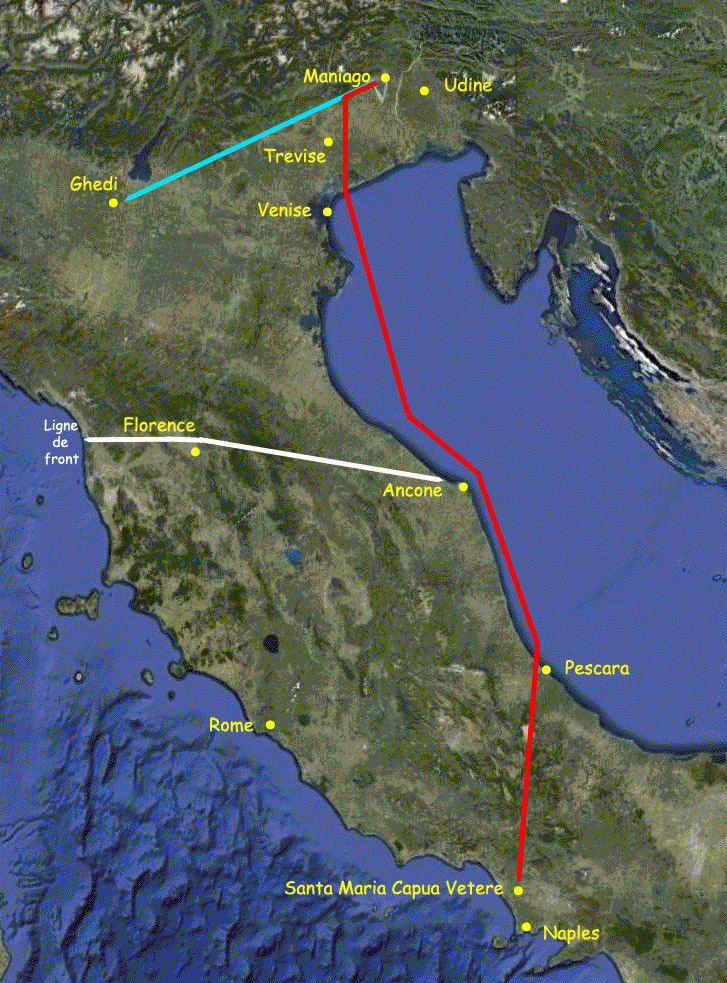

On July 25, 1944, Bf 109 G-6 160756 was on a formation ferry flight with fifteen other Bf 109s over northern Italy from Maniago, in the foothills of the Italian Alps, to Ghedi, 85 kilometers (53 miles) east of Milan. At the controls was a newly trained French-born Unteroffizier René Darbois, who was assigned to temporary duty at JG 4 July 17, having originally been posted to JG 53, which had just been transferred without him back to Germany.

However, Darbois had been secretly planning to use his Luftwaffe training to defect to the Free French Air Force, and just 20 minutes into the flight, he found his opportunity. Feigning mechanical trouble, he was given permission to divert and land at Treviso, just north of Venice. Despite convincing a German escorting him to let him be, he flew out of the formation’s visual range. He followed the Adriatic coast of Italy from Venice to Pescara, which he knew to be in Allied territory.

Upon reaching the airspace above Pescara, he turned west, intending to reach Allied-occupied Rome. However, he was disorientated in thick clouds while flying through the Apennine Mountains, and after emerging from the clouds and the mountains, he unknowingly headed southwest toward Naples. With fuel running low, he found an American airfield at Santa Maria Capua Vetere, near Caserta, where the personnel of the US Army Air Force’s 72nd Liaison Squadron, equipped with Piper L-4 Grasshoppers and Stinson L-5 Sentinels, were so far behind the lines in Allied-occupied Italy that they never expected to see a lone German fighter. Indeed, when Darbois lowered his flaps and landing gear, the signal lamp operator on duty flashed him permission to land without knowing it was a Messerschmitt Bf 109 until Darbois was on the dirt runway!

Darbois was soon taken into custody and, after a brief imprisonment in Rome, was allowed to join the Free French Air Force. Meanwhile, his Bf 109, Yellow 4, was ordered to be sent to the United States for flight evaluation testing. There, it was completely stripped of its Luftwaffe paint scheme and flown under the USAAF Foreign Equipment (FE) Branch serial number FE-496 at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, and Freeman Field near Seymour, Indiana, for the rest of the war, being compared against American fighters and being flight tested alongside other captured Axis aircraft.

After the war, it was one of many aircraft selected for preservation, to be sent to a former Douglas C-54 assembly plant at Orchard Place Airport in the Chicago suburb of Park Ridge (the airport is now O’Hare International Airport), and was formally transferred from the US Air Force to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air Museum (later renamed the National Air and Space Museum) in 1948, alongside other Allied and Axis aircraft of WWII set aside for preservation. By 1952, the collection that included the Bf 109 was evicted from Orchard Place and had to be moved to a new plot of land outside Washington, D.C., that became the site of the Silver Hill Storage Facility (now the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility) in Suitland, Maryland.

By 1972, the National Air and Space Museum began constructing a permanent location on the National Mall in downtown Washington, and the Bf 109 was selected to become part of the museum’s new WWII in the Air gallery. However, with no records from the Luftwaffe, a missing main data plate, and a stripped aircraft still wearing spurious German markings applied by the USAAF during WWII, the Smithsonian had their work cut out for them when it came time to determine the aircraft’s paint scheme. In the end, they chose the markings of Bf 109 G-6 Werrknummer 160163, coded White 2 with the 7th Squadron of the 3rd Group attached to Jagdgeschwader 27 in the Mediterranean. When the new museum opened on July 1, 1976, this was how the aircraft appeared, and it would maintain this appearance up until 2019, when the gallery was closed due to the extensive renovations to the National Air and Space Museum building, resulting in the aircraft moving into storage at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center.

But by this point, the aircraft’s true identity had been revealed. Though aviation author Thomas H. Hitchcock believed as early as 1976 there was a connection between the Smithsonian’s Bf 109 and the aircraft that landed at Santa Maria Capua Vetere in July 1944 based on comparing archival photos of the Santa Maria Bf 109 with details on the Smithsonian’s example that he extensively photographed for his book on the Bf 109 for Monogram’s Close-Up series, it was not until 1989 that future NASM curator Tom Dietz, following a theory posited by British researcher Nick Beale, who uncovered Allied reports of a Bf 109 G-6, Werknummer 160756, that had defected in July 1944, investigated the aircraft sitting in the gallery, and discovered a previously overlooked data plate on the cockpit armor plating that read ‘160756’.

In 1995, Jim Kitchens, an archivist at the Air Force Historical Research Agency at Maxwell Air Force Base, Montgomery, Alabama, confirmed through USAAF records that René Darbois was the pilot who flew Bf 109G-6 WNr 160756 to Santa Maria Capua Vetere. Based on this example complied over the years, the restoration department at NASM decided to repaint the aircraft in the markings of JG 4 when Darbois used it on his dash for freedom.

At this time, the aircraft’s restoration has now been completed, the National Air and Space Museum’s Messerschmitt Bf 109G-6 will be placed on display at the new Jay I. Kislak WWII in the Air gallery, alongside other WWII aircraft in the Smithsonian’s collections (as retold in this report HERE), which is set to open to the public by 2026. With that, René Darbois’ story can be told for the first time at the National Air and Space Museum, alongside the very aircraft in which he made his daring flight for freedom.

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.

According to the 72nd Liaison Squadron records, the tower operator at Capua airfield – squadron member Pvt. John F. Davis III – recognized that the aircraft was German, but because the landing gear and flaps were lowered he took it as a signal that the pilot wanted to land and was not planning to attack, so flashed the green “cleared to land” signal. When interrogated by squadron C.O. Maj. James Percy, Unteroffizier Darbois said that he and three other pilots of JG4 defected together but they “encountered a storm” over the Adriatic, “whereupon he lost his friends” and continued on alone. The 72nd kept Rene Darbois under guard overnight in the “armament shack” (of all places!) and intelligence officers from the Allied Force HQ collected him the next day, while his plane was later “taken over by the Navy”. In the meantime, the 72nd personnel stenciled, “CAPTURED BY 72nd LIAISON SQDN. JUL 25 1944” on the fuselage in white lettering below the left front windscreen.

James H. Gray

Liaison Aircraft Historian

Sentinel Owners & Pilots Association

Beautiful! I am of German heritage and I love the BF-109’s. I live in WV, I need to take a trip to see this beautiful plane!