by Adam Estes

In recent years, the Yanks Air Museum of Chino, California, has endeavored to return certain aircraft from their extraordinary collection back to the air, with first their Stinson L-5 Sentinel and then their Curtiss Kittyhawk taking flight. Now, they can add Bell P-63A Kingcobra N94501, s/n 42-69080, to that growing list. Nicknamed Fatal Fang, the historic aircraft took to the skies again on Thursday, November 30th, 2023, after more than 40 years of dormancy in this world-class collection. Experienced warbird pilot Mark Todd was at the controls.

As many readers will know, the Bell Aircraft Corporation’s P-63 Kingcobra was a development of the company’s earlier P-39 Airacobra. Although underpowered at high altitudes due to its lack of a dual-stage supercharger, the Airacobra was highly effective lower down, and highly useful on the Eastern Front in Soviet use. For American forces during WWII, the type, along with the P-40 Warhawk, also helped hold the line in the Pacific and Mediterranean Theaters until more advanced fighters such as the P-51 Mustang and P-47 Thunderbolt arrived on the scene.

While the larger P-63 retained the P-39’s mid-engine configuration, armament, and unusual ‘car-door’ cockpit entry system, it did come fitted with an additional supercharger and a re-designed, laminar flow wing. Additionally, the Kingcobra incorporated other features addressing deficiencies that P-39 pilots had noted. Although the P-63 proved more capable than its predecessor and was ordered into production, the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) never fielded the type on the front lines, since the superior P-51 Mustang was already in mass production by the time of the P-63’s first flight of December 7th, 1942.

Nevertheless, the Kingcobra was not a wasted development. While some P-63s served in stateside fighter units, the type’s primary USAAF role was as a manned aerial gunnery target for training air gunners how to both track and shoot down enemy aircraft from a moving platform. While flying in another aircraft, typically a bomber, trainee gunners could shoot at RP-63 Kingcobra targets, learning how to lead the aircraft in the air with their weapons, which fired ‘frangible’ bullets. Made from a lead/Bakelite composition, these bullets would largely disintegrate upon hitting the heavily armored RP-63. Sensors mounted to every surface on Kingcobra would detect any bullet strikes and trigger the illumination of a light bulb within the aircraft’s propeller spinner (in the former 37mm cannon position) and on marked side positions, showing the accuracy of the gunner’s aim. This led to the RP-63 receiving the unofficial nickname of “Pinball”.

More than 70% of all P-63s built were supplied to the Soviet Air Forces. While the type arrived in their hands very late in the war, they did fly some of their Kingcobras in combat against the Japanese in Manchukuo (Manchuria) during the final days of WWII. Since the P-63 was believed to be still operational with the Soviets into the early 1950s, it received an official NATO identification code, “Fred”. The French Air Force also used P-63s, flying examples in the First Indochina War until replacing them with Grumman F8F Bearcats, due to a lack of spares. The Fuerza Aérea Hondureña (Honduran Air Force) also operated a handful of surplus US Air Force examples, purchased from the United States in 1948.

While most surplus Kingcobras met their ultimate fate in a scrapyard, a few examples found their way into air racing and, later, preservation. However, just four of the breed were airworthy as of December 2023, with the Yanks Air Museum’s example adding to this number.

The Yanks Air Museum’s Kingcobra is P-63A-7 42-69080. It rolled off the Bell Aircraft production line at their factory in Buffalo, New York during spring 1944, with the US Army Air Forces taking delivery on May 8th. The fighter spent the war years assigned to various bases in California (Chico, Palmdale, and Muroc), Oregon (Portland), and Washington State (Everett). In October 1945, the Army Air Forces officially struck the aircraft from their books, transferring it to the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC). It moved to the RFC disposal facility in Ontario, California (now the site of Ontario International Airport. It is worth mentioning that a satellite field to RFC Ontario existed at Cal-Aero Field, now Chino Airport, where additional aircraft were either sold off or scrapped.)

In 1950, the Cal Aero Technical Institute purchased 42-69080 for their facility at Grand Central Airport in Glendale, California (just north of downtown Los Angeles). Here the aircraft served as an instructional airframe for aviation maintenance students and was allocated the civil registration NX32750. Grand Central Airport had been one of the pioneering airfields of the Golden Age of Aviation. Furthermore, many classic Hollywood films once used it as a backdrop. And, of course, it had a role as a training base during WWII. However, by the 1950s, the postwar development of the Los Angeles metropolitan area was catching up to Glendale, eventually leading to Grand Central Airport’s permanent closure in 1959 … but not before famed warbird collector, and Planes of Fame Air Museum’s founder, Edward T. Maloney acquired the Kingcobra from Cal Aero in 1953. (As an aside, Maloney also acquired the Curtiss-built P-47G 42-25254 and Messerschmitt Me 262 A-1a/U3 WkNr 500543 from Glendale too. Maloney stored these aircraft, and several others, on his family’s property until opening The Air Museum, now Planes of Fame, at a former lumber yard on Route 66 in Claremont on January 12, 1957.

42-69080 remained with the museum as a static display, moving to Ontario Airport with the collection in 1963, before ultimately arriving at Chino Airport by 1973. Though not flown, it was registered as N32750, following the Cal Aero registration, later, in 1976 gaining N94501 – which it retails to this day.

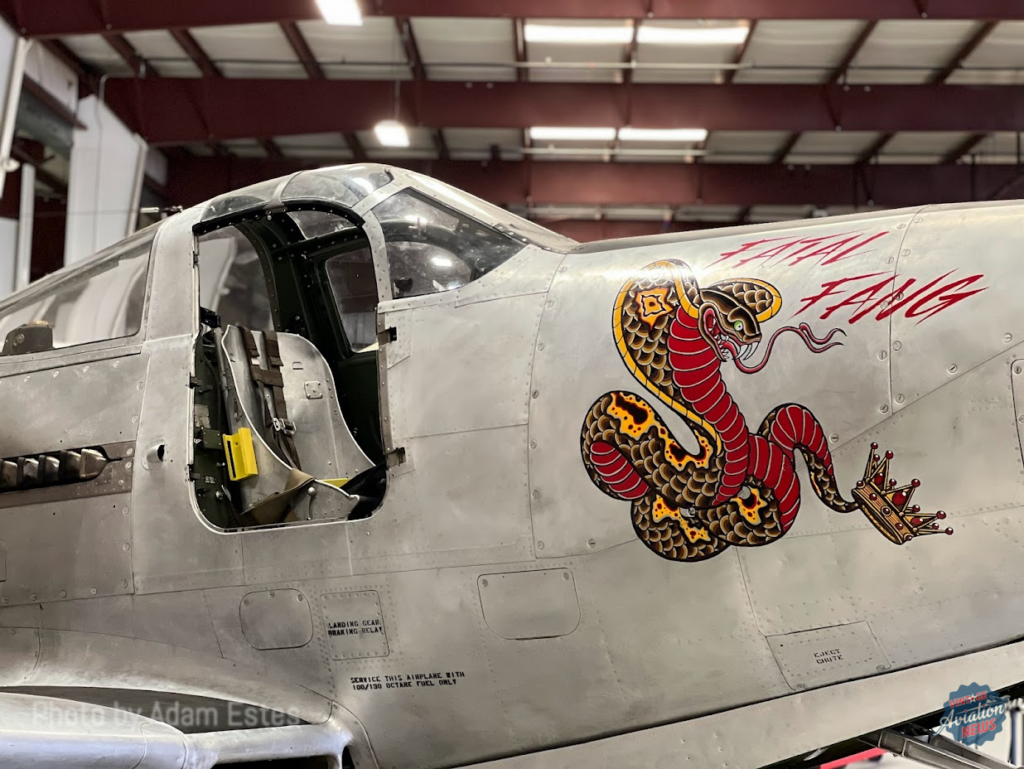

In 1973, another warbird collector was also beginning to establish himself at Chino Airport. Charles Nichols acquired his first historic aircraft, a Beech Staggerwing, in that year; it remains in his collection to this day. Nichols acquired P-63 42-69080 from Ed Maloney in September 1977. The retired fighter joined what was then known as the Yankee Air Corps. While the aircraft was registered with the FAA and restored to airworthiness in 1979, it flew only rarely and mostly just sat on display in the ever-growing museum (now known as the Yanks Air Museum). By this point, the P-63 had gained its nickname, Fatal Fang, along with some nose art depicting a king cobra wearing a crown.

The longer the aircraft, along with many others at Yanks, sat on display, the more and more people across the warbird community began to declare that Yanks’ planes would never fly again. But in recent years, things have begun to change. Following the restoration of Yanks’ UC-40A they have accumulated 200 hours with Frank Wright as pilot in command. They have also completed the Stinson L-5 Sentinel and Curtiss P-40E Warhawk (a former RCAF Kittyhawk Mk IA). The restoration of Fatal Fang began on May 7th, 2018. Its Allison V-1710-111 was sent to the Yancey Allison Enterprises workshop in Chino to be overhauled by Joe & Pat Yancey. Meanwhile, the Yanks’ Flight Team, led by Frank and Casey Wright, worked tirelessly on the aircraft’s complex electric system, the landing gear assemblies, the cockpit, and flight controls. In addition to this, the nose art was reimagined, and while the aircraft maintains its bare metal finish, the roundels and stencils have been redone to be as accurate as possible to the time of the aircraft’s Army Air Force service.

Unlike most museums the COVID shutdowns actually streamlined the project as Yancey and the father-son team continued work on the engine and the nose gear reduction box, completing both before normal operations resumed. In 2021, the Allison engine returned was re-installed and run by Casey for the first time in the airframe since 1979. Following the engine runs, every system on the aircraft was checked and rechecked to get everything right. But all of that effort in blood, sweat, and treasure was worth it when on the morning of December 1, Fatal Fang made its long-awaited return to the skies and arrived safely back down. We celebrate the achievement of the museum on this painstaking effort and look forward to seeing more of Fatal Fang in the coming years.

For this important first flight, the Yanks Air Museum worked with Warbird pilot Mark Todd. Mark has been flying the CAF Airbase Georgia’s P-63 for many years and is currently one of the most experienced pilots in the type. We were able to catch up with Mark after the second flight and this is what he told us.

VAN: How did you get involved with the Yanks Air Museum?

MT: About three years ago fellow warbird pilots Chuck Gardner and the late David Vopat introduced me to the folks at Yanks. I flew in their P-40 Warhawk a handful of times and they wanted me to come on board to help with the P-63 and ultimately fly it once they had it ready, which we did.

VAN: Tell us about the overall experience with the airplane and the first flight.

MT: Overall it flew great! The airplane flew forty-something years ago and it looked like a functioning airplane. All the big pieces were there. It looked like it was ready to go, but under the skin, it had been sitting for a while. So it was a significant effort by the museum’s team to get it ready. They went through everything, the propeller, brakes, gap-sealed ailerons, shimmy damper, etc. When you rig it to the book specs and in theory if everything’s rigged right, it should fly right. But still, stuff comes up. But I’ll tell you, the first fly, it was very uneventful. It flew just like it was supposed to, just a handful of little squawks, to be expected, but nothing that kept just from putting it back up in the air within another hour we got another flight on it. So she was [the airplane] really smooth right out the gate. We did three flights. We did two on November 30th and one on December 1st. And we’ve got about an hour and five minutes of flight time between the three flights on it now. Great work by the Yanks’ team!

VAN: Was this the first time that you flew a warbird post-restoration, or did you have the opportunity to do test flights before?

MT: I flew the CAF’s P-40 after it went through significant refurbishment and repairs after it had a landing gear incident where a landing gear had failed. So I was part of that, but other than that, just flights that I would categorize as “returned to service” when the airplane was down for a while, but this is the first one that I’ve flown that had been down for so many years and had such significant work done to it.

VAN: How do you prepare yourself for such a test flight?

MT: First of all, you look at the book and just make sure that you’ve got all your basic operating numbers in mind, and then review any sort of emergency procedures that you haven’t gone through. There’s not a whole lot of them, but I mean whether it’s putting the gear down or the glide speed or just some stuff like that, you familiarize yourself with that to make sure that in the event something does occur that you’re ready for it.

For sure you conduct a more extensive preflight, pulling panels off, making sure everything is where it should be… All the fasteners are correct hose clamps are tight, parts are all tight, etc. Just a very thorough preflight with it. In this case, I went and taxied it and I did take it down the runway at high speed because a big thing in the Cobra is the nose wheel damper for the nose gear. And if that’s not happy and you get a shimmy going, it could be pretty violent. Having had two friends I know that have experienced it, it’ll rattle your brain. So that’s something that you want to check for and make sure that it’s happy. With this thing being a free castering nose wheel, you have no direct control of that nose wheel, which a lot of people don’t think to realize. So brakes are vital and that shimmy dampener is vital for a safe operation for keeping on the runway.

So in this case, I got familiar with the brakes, made sure they felt good, and when I had a feel for them, for when I needed them if I needed them. Of course, the run-up, running it up, running the trims full in both directions, make sure all the cables are happy. I mean, the plane had been signed off with inspection, so in theory, it should be good, but you still want to go the extra mile to make sure everything’s dialed in.

VAN: What’s the next phase?

MT: We’ve got two other pilots that are going to be flying it, Taylor Stevenson and then Chuck Gardner. Chuck’s getting his rating in his LOA right now so he can be authorized to fly it. But between the three of us, we’re going to be flying it. We’ve all kind of agreed that we want to get five hours on it at a minimum before it leaves the traffic pattern or the general airport area. Just continue to build our confidence up and get some more time on it. So we’re going to try to do that in a reasonable amount of time. We’re probably going to try to get that done, hopefully by the end of December, if not the beginning of January, at least get those five hours knocked out.

To learn more about the Yanks Air Museum, please visit www.yanksair.org.

Related Articles

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.

I love your coverage of historical and accurate aircrafts. The only regret is being forced to change the total units recognition. I will cling to (Confederate) Ret CAF Cornel D Reed

It’s good that after the CAF lost their P-63, though a two-of-a-kind Kingcobra prototype, we have another one in the skies once more.

P-63 Cobra, updated newsletter.