This past Thursday marked the 64th anniversary of the tragic accident which claimed the life of legendary WWII fighter ace, Don Gentile. WarbirdsNews contributor, David Cohen, has investigated the causes behind Gentile’s crash, which also took the life of his passenger, Sgt.Gregory Kirsch. He has visited the accident site on a couple of occasions in the past two years, and we thought our readers would be interested in his report.

The Last Flight of Don Gentile

by David Cohen

Don Gentile needs no introduction. Whether known as ‘Captains Courageous’, ‘The Two Man Air Force’, ‘Messerschmitt Killers’, or ‘Damon and Pythias’, the exploits of he and his wingman, John Godfrey, with the 4th Fighter Group are well documented. Less well known are Gentile’s early days in his hometown of Piqua, Ohio, nor those after World War II leading up to his untimely death in 1951. His life still resonates enough with some in Piqua for one resident to make the 8 hour drive to Maryland in the hopes of discovering more about Don Gentile’s last flight.

Gentile was born in Piqua in 1920. He held an abiding passion for flight from early in his childhood, earning his pilot’s license by age 17. Gentile was a daredevil in the air and made sport of several Piqua landmarks, which included flying under the Shawnee Bridge, circling tightly around the spires of St. Boniface Catholic church, and of course buzzing his girlfriend’s home. It was no wonder that Gentile wanted to join the Army Air Force when war broke out in Europe, but at that time they were only accepting college graduates. So Gentile went north to volunteer with the Royal Canadian Air Force in Canada, and from there to the Royal Air Force and the deadly duel with the Luftwaffe over British skies.

After flight training, Gentile received a posting with 133 Squadron, one of the three fabled “Eagle Squadrons”, flying Spitfires from Biggin Hill in England. He scored his first two kills on August 1st, 1942 during the ill-fated Dieppe Raid. On September 29th, 1942, the US Army Air Force formally absorbed the Eagle Squadrons into the nascent 4th Fighter Group where they transitioned onto the much heavier P-47 Thunderbolt. Gentile scored another 2.33 kills before the 4th FG re-equipped with the P-51B Mustang. The Mustang proved to be the perfect mount for Gentile. He and his colorful P-51B nicknamed Shangri-La racked up an amazing 15.5 kills between March 3rd and April 8th, 1944. See a short video clip of Gentile with his Mustang below.

By April 8th, Gentile had become the highest scoring American ace in Europe. Five days later, Gentile was performing for a group of newspaper and newsreel reporters in his Mustang. Gentile made repeated high speed passes for the cameras, becoming more aggressive with each attempt. His old daredevil habits from Piqua had returned in full, though this time his recklessness got the better of him, and he ploughed the Mustang into the mud, destroying it in the process, though somehow wounding only his pride. The 4th Fighter Group’s commanding officer, the equally legendary Don Blakeslee, was so incensed by Gentile’s actions that he grounded him on the spot and sent him back to the USA. For him the war was over…

Upon his return from Europe, Gentile made the obligatory War Bond Tours, flying around the country in a P-51D painted to represent his original Shangri-La. Once the War Bond tours ended, Gentile briefly became a test pilot and gunnery instructor at Wright Patterson Field, in Dayton, Ohio, not far from Piqua. He married Isabella Masdea and started a family. Some time later, Gentile moved to the Washington D.C. area to become an undergraduate student at the University of Maryland, pursuing a degree in military sciences while still attached to the United States Air Force.

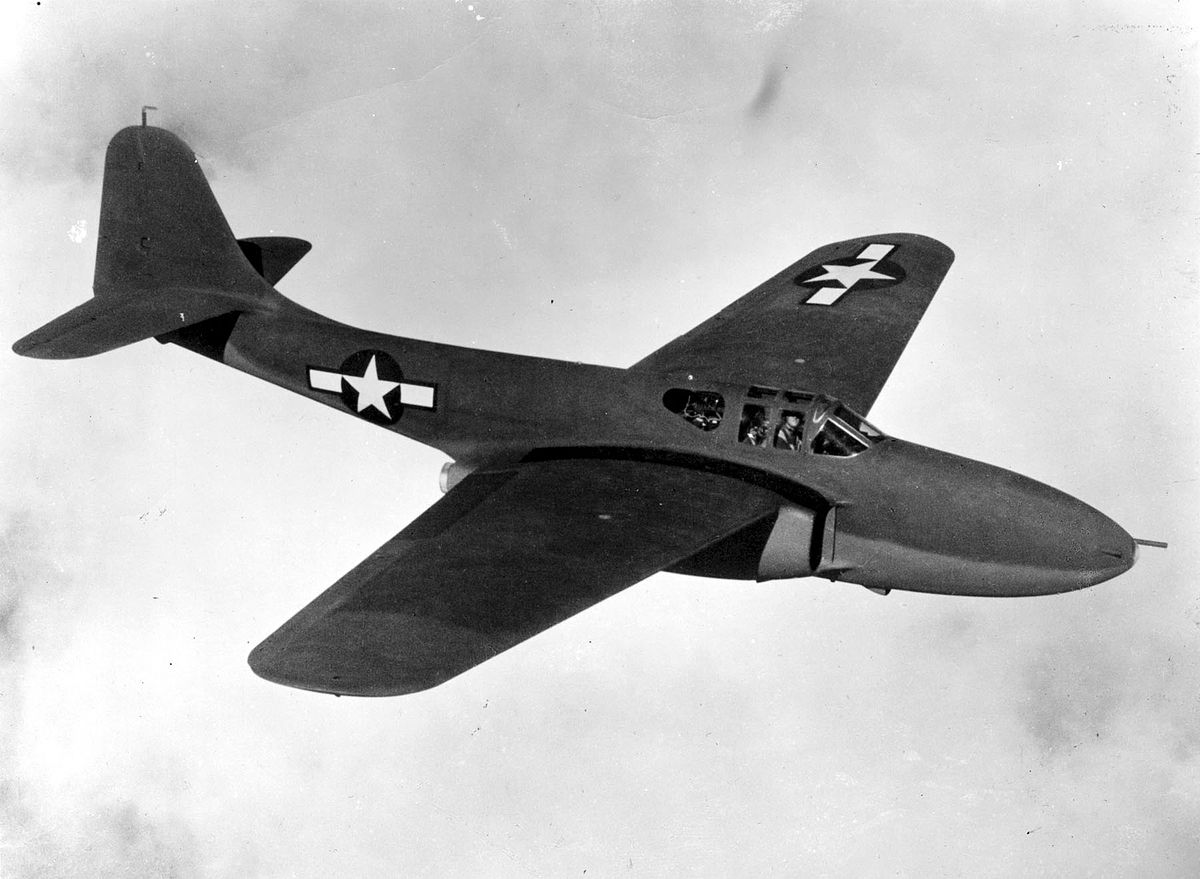

In January 1951, Gentile began refresher training on the Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star at Andrews AFB. While Gentile had amassed nearly 4,000 flying hours, only about 20 these were in jet aircraft, and none since 1945. His jet time was mostly in the YP-59 Airacomet, although he did have some in the F-80, the T-33’s forebear. The biggest difference between the F-80 and T-33, besides the rear seat and second set of controls, was the F-80’s greater fuselage fuel tank capacity which held 200 gallons as opposed half that for the T-33.

Prior to his check ride in the T-33, Gentile had to take a written test on the various procedures involved in its operation. He scored about 90 percent on the exam, and an instructor walked him through areas he was unfamiliar with. Among his mistakes on the questionnaire were the procedures for re-starting the jet engine in flight. Both the difference in fuselage tank fuel capacity between the F-80 and T-33 as well as the “air start” procedures would loom large in Gentile’s final flight.

Gentile flew familiarization flights on January 24th and 25th with the instructor pilot in the rear. Gentile’s flamboyant flying behavior again showed itself on this hops, as he dropped his altitude below 1,000 feet at times. He also buzzed his home in nearby College Park, Maryland, much to the consternation of the instructor pilot. Gentile was scheduled to fly on Saturday, January 27th, but his T-33 was unserviceable. It would not be ready until the following day.

Sunday, January 28th, 1951 was an unusually warm day for the region, with temperatures around 50°F. Gentile returned to Andrews AFB to continue his familiarization flights in T-33A serial 49-905. Captain Ray Woods sat in the rear seat on the first flight. The T-33 taxied out and took to the sky, only to return 15 minutes later. Gentile indicated that several cockpit instruments and the radio were not operational, but Sgt. Baron, the plane’s crew chief, pointed out that the circuit breakers needed resetting. Gentile indicated to Baron that he understood the circuit breakers were not to be reset until after landing, but this was apparently not the correct procedure. When Baron pushed in the circuit breakers, the instruments began working again. He then began servicing the plane to prepare it for another flight, which mostly consisted of topping up the tanks with jet fuel. Captain Woods, however, declined to fly with Gentile on the subsequent flight.

Gentile returned to his Shooting Star about 25 minutes later and settled into the cockpit. Twenty year old Sgt. Gregory Kirsch, a control tower operator at Andrews, walked up to the legendary ace and asked if he could ride in the rear seat. Gentile agreed, so Kirsch went about getting the necessary permissions, clearances and gear for the flight. Sgt. Baron and his assistant Sgt. Devol helped Kirsch into the rear cockpit and went over some of precautions and procedures he had follow during the hop.

Gentile started up the T-33 and taxied to the runway, taking to the air at about 3:05 PM. He made two circuits around the airport at fairly low altitude and then disappeared from view to the northeast. It would be the last time anyone would see Gentile or Kirsch alive.

While flying around northeast of the base, the T-33’s J33 engine flamed out. Gentile began gliding back in the general direction of Andrews. Despite his efforts, he was unable to restart the engine, and his already low altitude was getting squeezed further by a steady descent while facing rising terrain. It was at this time that Gentile spotted a flat clearing to his left so he banked sharply in an attempt to reach it. The severity of this turn coupled with his still declining altitude, forced the T-33’s left wing to clip a line of trees, which hurled the trainer downward at a 50 degree angle into the ground. The following explosion and fire consumed much of the aircraft. Gentile and Kirsch never had a chance.

A pillar of black smoke came to the attention of the Andrews controllers at about 3:18 PM. They asked the crew of a Navy P2V Neptune on final approach to investigate. The first Neptune circled the site but could not determine the cause of the fire. A second P2V headed to the site and they concluded that it was indeed the result of an airplane crash. The crash bells at Andrews rang loudly and fire equipment raced to the site. A third Navy plane, a Beech JRB Expeditor had taken station over the crash site and continued to circle it until the fire equipment arrived. The rescue crew found Gentile’s body thrown 15 feet from the wreckage, still strapped into his seat, but the crash impact had forced Kirsch’s body through the bottom of the demolished cockpit.

The tail section from Gentile and Kirsch’s T-33. (crash report photo via David Cohen)

Being late afternoon in January, darkness was already beginning to fall as the rescue team extinguished the fire and recovered the bodies. The Air Force removed most of the major wreckage pieces and returned them to Andrews for the crash investigation. They soon released the bodies to their families for burial. Gentile’s family held a funeral mass for him at St. John Baptist Church in Columbus, Ohio. People jammed both sides of High Street in the city as the funeral procession made its way to Saint Joseph Cemetery in Lockbourne, Ohio, for the burial. Gentile was 30 years old and left behind his wife and three young boys.

The Air Force investigation focused on the engine, as two eyewitnesses indicated the plane was gliding and not under power at the time of the crash. They found no problems with the engine. Damage to the turbine wheel indicated that it was rotating at a very slow speed at the time of impact, confirming that the plane was not under power. The fuel pump provided the best clue. Its gear teeth had worn abnormally and expanded so that they scratched the inside of the pump housing. This could have only been due to a lack of fuel, as without being under load, the pump would have revved well above its design parameters.

The Air Force came to the following conclusions in their report:

- The aircraft crashed as a result of a flame out.

- The flameout was due to improper fuel management by the pilot who had allowed his fuselage tank to run dry, and did not switch to his tip tank, wing tank or leading edge tank in sufficient time to prevent fuel starvation.

- The pilot attempted an air-start after the flameout, but insufficient altitude denied the required time to effect a successful re-start

- The pilot used poor technique by not gaining more altitude immediately after takeoff.

- The pilot was not sufficiently familiar with the T-33 even though his check out had complied with all current Directives and Standard Operating Procedures. The records indicated that the pilot had only 2:50 hours jet time since 1945.

- The current command regulations were written in such a way to allow inadequate checkouts, and therefore needed amending.

The Air Force did change their command regulations and mandated that the checkout questionnaire had to be passed through study rather than using reference material and/or instructor feedback. In this case, Gentile’s apparent lack of knowledge in the differences between the F-80 and T-33 fuselage tank capacity and the air-start procedures, combined with his own penchant for low altitude flying, proved to be a fatal combination for both himself and his passenger.

Back in Ohio, Gentile remained a local legend well over a generation after his death. Greg Covington, a Piqua native, grew up hearing the stories of Gentile’s daredevil flying in and around Piqua as well as his heroics during World War II. As he got older, he worked for a grocery store and would deliver groceries to Gentile’s father. One of the topics that bothered Greg was that there was very little known about how Gentile passed, and even the stories in Piqua often seemed to contradict each other. Greg chose to set about researching the crash and find out as much as he could. He obtained the crash report from the Air Force and began to study it. On slow nights at this job as an overnight X-Ray technologist, he would compare Google earth maps to the crash report maps. Then, one day, the pieces clicked in. The Google Map nearly matched the crash map, and at least from the pictures, it appeared the crash site was undeveloped. Could this be true? Greg needed help from someone local to the site to find out if his instincts were correct.

I had just embarked on my first venture into wreck site investigation, the June 22nd 1957 crash of a Capital Airlines DC-3 in Clarksburg, Maryland, and posted my findings on an internet forum: www.wreckchasing.com. I was intrigued by the Gentile crash site and began looking into it on my own. I found that the information was sketchy and contradictory. I picked a spot that I thought was the most likely area and considered heading out there.

Greg saw my posts about Gentile on the forum and reached out to me. He was convinced that he was very close to determining the crash-site location. On reviewing his research, I agreed with his conclusions, in direct contradiction with my own prior supposition. Now came the tricky part of identifying the current landowner and securing their permission for an on-site investigation. A search of the Maryland land records turned up the landowner, but after repeated attempts I failed to obtain his permission to search the property. I therefore chose to write a letter, explaining to him who we were, what we were looking for and how we would handle ourselves. The letter did the trick, and the landowner gave us access to his land, but with the condition that we had to keep the location confidential.

With permission granted and a letter from than landowner in hand, we could now move along with an actual expedition to the crash site. The big question was when to go. Digging in the winter was out of the question, as the ground would be too hard. If we waited too far into the spring, we would have to deal with something I call the “green explosion”, the time when undergrowth suddenly resurges into life, making any kind of ground search far more difficult. That left us with a search window from roughly the end of March to the beginning of May. To complicate matters further, Greg’s wife was close to giving birth to their second child. We had to wait for the baby’s arrival before making any concrete plans. Based on the baby’s due date, we figured we’d end up heading to the site around the second or third weekend in April.

In the meantime, Greg and I continued to analyze and re-analyze the crash report data. We closely examined the Google Earth maps and kept moving around our probable point of impact. The one thing I learned from my experiences in Clarksburg is that everything is far closer together than it appears on Google Maps and even the crash scene photographs. At night, I even had nightmares that I’d picked the wrong property to obtain permission from. Further discussions with the landowner regarding certain topographical features did, at least, convince me that I got the property location correct.

Greg’s son came into the world on March 22nd. With his arrival, we could now make definite plans to visit the crash site. We picked the second weekend in April. Greg would rent a car, drive the eight hours from Piqua to the Washington, D.C. area on Friday. He and I would meet to go over last minute details and figure out a “battle plan” for the site. We would then head out to the site; each one of us to be joined by one a friend. Greg’s friend Capt. John Stein, also a Piqua native, would come up from Virginia. The visit to the crash site was going to be a one-shot event. There could be no postponement or do-over. We had to be prepared to handle whatever Mother Nature would throw at us.

Mother Nature did try her best to throw us a curveball. Two 90°F days earlier in the week hastened the appearance of the “green explosion”, which was followed by severe storms that could have impacted Greg’s travel plans. All went well on the trip though, and Greg and I met in person for the first time on Friday afternoon. We had one bit of final anxiety though, as we noticed that terrain features were almost identical in an adjoining property, which is typical of this section of Maryland with undulating hills separated by valleys with streams. Could we have erred and picked the wrong property? The evidence, particularly the eyewitness testimony, seemed to support our original analysis, but we just couldn’t be sure until we were actually on site. We did know that the adjoining property was also owned by the same individual, so we could only hope he would let us poke around there if we’d made any mistakes.

Saturday, April 13th dawned chilly, but clear and sunny. One of the landowner’s employees had unlocked the gate to the property and our vehicles bumped down the ill-maintained gravel driveway. It became immediately apparent that everything was far more compressed than we’d seen in the pictures. A quick scan revealed an extraordinary sigh thought – a tree with its trunk sheared off and other limbs growing up around it. A short hike towards the tree revealed the ravine described in the crash report. Greg’s research was near perfect. Instead of spending our morning looking for the point of impact, we found ourselves exactly where we needed to be. I looked at Greg and told him, “Congratulations. You did it!”. We soon found a depression in the earth about 20 yards from the sheared tree. You could draw a line of 45 to 50 degrees straight to the area where the tree was damaged. Our thrill at finding the exact spot was muted with the sudden realization that we were standing on ground where two men had lost their lives.

With the crash site pinpointed, came the exacting work of searching the property with a metal detector and marking the “hits” with flags and recording those locations with a GPS unit. Greg is quite experienced with a metal detector, and had bought a brand new one specifically for the purpose of exploring the wreck site. As we marked each hit, we noticed that a debris field was clearly emerging. Once we had about a dozen “hits” marked, we began the painstaking process of excavating each spot and sorting through the dirt using a pinpoint detector. We did unearth some regular junk, such as pull tabs from old aluminum cans and a couple of coins, but small pieces of airplane were also coming to light from approximately 6 to 7 inches below the surface.

Unfortunately, I had to leave at noon, but Greg and John continued marking and digging for another couple of hours. The day’s work had yielded about a dozen artifacts that were likely from Gentile’s doomed T-33. The expedition was successful enough that a second expedition to the site was planned for the following March.

Our second expedition was much easier with the landowner, as we had earned his trust. Greg had also become quite the virtuoso working the metal detector in the year since our last visit. Once again, Mother Nature threw a curveball at us, including snow the Tuesday prior to the site visit and predictions of heavy rain for the Saturday. Fortunately, the heavy rain held off, and with periodic drizzle and showers, Greg and I managed to recover about another dozen artifacts from the site. The most significant of these artifacts was a nearly intact ignitor that could only have come from a T-33, thus giving us our “smoking gun” and the one artifact that could truly tie in all the others we’d found to having come from Gentile’s ill-fated jet.

We have fully documented all the artifacts recovered and have been moved them to where this story first began, in Piqua, Ohio. They will help tell the final chapter of Piqua’s favorite son, Dominic Salvatore Gentile.

So he takes off at 3:05 PM and crashes at 3:18 PM. He was in the air for thirteen minutes and his 100 gallon fuselage tank runs dry??? I know jets suck a lot of fuel but 100 gallons in thirteen minutes is hard to believe. The article suggests the tanks were topped off before the flight. Something doesn’t sound right.

I’d like to add that the USAF only assumed that Don’s fatal crash was caused by improper fuel management since he crashed about 15-20 minutes into his flight which is approximately the time the amount of fuel in fuselage tank allowed. SOP in the early T33 was to switch to wing tanks as soon as altitude was reached. It’s not clear what the procedure for the P-80, which Gentile had flown in the past, might have been for fuel management. Officially, his engine flamed out which was very typical of the early model T33-A jets. He was noted flying at 1500 feet which seems low but was well within the parameters of his flight plan and regulations of the time. He was attempting an air restart at 1500 feet. Early ejection seats required a much higher altitude than this and coupled with the fact he had an untrained passenger with him, caused Gentile to look for a belly landing site. He banked hard left at about 200 ft altitude and clipped a tree with his wing catapulting him into the ground. He fought the jet till the end looking for solutions all the way to the crash. Those early jets killed many pilots regardless of their level of experience.

Thanks very much for the additional details Greg… You and David did some great research into this, and we really appreciate hearing from you!

It should be noted that Gentile’s T-33 – a 1949 model – had no ejection seats. These didn’t become standard equipment in T-birds until FY 1951 serial aircraft. ’48, ’49 and ’50 models had the same seat as the P-80A… like you’d find in any P-38.

Gerald always precise and competent 😉

This is interesting. The USAF crash report lists specifically as two ejection seats “not fired”. I spoke with an early T33 pilot a few years ago. His was equipped with ejection seats but e walked me thru the ejection procedure and there is no way at 1500ft it could be accomplished. There’s a vid clip out there online of Don Gentile getting ready to board a P80 at Wright Field and he’s clearly wearing his chute. Interesting stuff

Even much later many a jet pilot was killed in flying accidents because the technology still was unreliable. There triple ace Joseph C. McConnel comes to my mind…

But i am stunned the Airforce handled familiarisation to then very untryed jet aircraft so careless!

Hi Tim, The T-33’s Allison motor is capable of burn rates in excess of 400 gallons per hour at low altitude and at high throttle settings. 15 minutes of flight at 400 gallons per hour yield 100 gallons used. We know Gentile used full throttle for takeoff, and given his penchant for low level flying at speed, likely kept the throttle at a high setting. That is the knock on the T-33 in private hands. It is a relatively inexpensive warbird to acquire, but it’s maintenance and operational costs are very high. Thanks for reading the article and your interest in the topic!

I had the opportunity to locate Don’s boyhood home in Piqua. It would seem appropriate to place a historic marker or plaque near the home.

Don has a full size bronze statue in downtown Piqua

Flying near the edge of the envelope is always risky. Many great men died in non-combat related crashes. May they all rest in peace.

Great work, great article. I always enjoy reading about these old timer heroes.

But another example of great skills, maybe not so great judgment that finally caught up with him.

Don Gentle had great judgment from the time he first flew when in his early teens. It was the lack of training and procedures that killed him, not lack of judgment. You did not know him.

Alma Stricker Mellinger (formerly of Piqua, Ohio)

My father Emmett Davis was friends with Mr Gentile and his father we are from southern Ohio. He was there when he crashed he was a firefighter and drove the crash truck and he was waiting on dad and sitting on the wing and when dad got there he asked Him what took him so long! I have a lot of stories from my father and many pictures of the base and Don, my father also donated many pictures to the Dayton Air Force museum. My father passed away last fall but talked about his time in the service up until he passed, he was very proud of this and the smile it brought to his face will always stick with me.

Thank You David Cohen for a very detailed analysis of Don’s last flight – my Dad (John D. Gentile, 4th Div. Marine Corps ’42-’45, radio operator, AGC-1. 1924-2010 – Don’s cousin) told me about Don when I was very young, which piqued my interest in all things aviation. Never knew that much about his demise, just ‘pilot error’ until your article. I certainly appreciate the depth of your ‘investigation’ – thank you again so much for the article. Don still one of the great combat pilots of WW2! (If interested, my Dad grew up in Wash. D.C. area settled in Denver because he got stuck in a blizzard after discharge on a train home to D.C. from Treasure Island (Nov. ’45), liked the climate, had had enough of bugs, humidity after service in South Pacific)! Thanks and Sincerely Yours, Andrew in Colorado

Thanks very much for writing in Andrew! Fascinating stuff. I will pass along your details to the author.

Did you contact any of the immediate family of Don Gentile? There is more background for your story, especially that fateful Sunday.

I’ve been in contact with Joe Gentile several times as well as Don’s sister, Edith about a year prior to her passing. My main focus in investigating the crash was due to the disparaging remarks about Gentile by Chuck Yeager. I shared the crash report and all my information with Joe who expressed an interest in visiting the site with his brothers if the timing ever works. I’d would love to hear any additional information anyone has

Thanks for your insightful informative work, Mr Don .S.Gentile was a child hood hero of mine, there was lot of misinformation on his untimely demise, (R.I.P.) but thanks to your dedication and perseverance I feel a lot of

Confidence in your truth finding mission, thank you Sir.

Thank you for this great work and great read, further memorializing an American hero.

He was one of the ‘American Eagles’ who came to Britain and fought with distinction in the Royal Air Force. They will always be honoured.

I do believe that under King’s Regulations, now Queen’s regulations (it may not have been amended) ; an American Officer/Pilot, Serving within the RAF, is (particularly if he comes from ‘the West’ Especially TEXAS, is permitted to wear cowboy boots in his No1 Dress (parade dress ie with sword etc) they do however have to be black leather.

I absolutely love this Allowance for Texicans & their Western Foot Wear.

I heard about Don from his son Dominic, who worked for the same company I did. It’s a shame Don never received his MOH.Great pilot of ww2

D Gupton,

Was this the Dominic who served in the Coast Guard in the late

1960’s?

USCGC GENTIAN WLB 290

Thanks, Paul Knowles

My father, Lee Bowman, Sr. was a well-known movie actor, who accompanied Dom Gentile and Johnny Godfrey on their ‘Bond Tour’…….They visited our house in Santa Monica, California, on the tour, and my parents were honoured to introduce them to a number of Hollywood celebrities.

I will visit the Eagle Squadron Memorial near the U.S. Embassy to pay my respects now that I have read this terrific article.

Lee Bowman, Jr.

London, U.K.

Lee thanks for the nice comment! David did an incredible job with this article.

As a child ,I remember my neighbor ,an older man being close friends with Don’s father I believe . I grew up in piqua ,on Adams Street and remember hearing them tell stories of his flying days in piqua , we have always been very proud of our flying ace here in our small town . Thank you so much for your article.

My family is from Piqua and we lived in Troy. My dad used to tell me stories about Maj Gentile flying around Piqua. He still attends mass at the church that was used in some of the stunts. Those stories had some influence in my decision to enlist in the USAF.

FYSA, another Heroic Son of Piqua is getting a major motion picture. The Last Full Measure will be about MOH recipient Airman William H. Pitsenbarger, Jr.

Just a small correction…. Don did not fly under the shawnee bridge. Don’s father, Patsey, told me that he flew under the old N.Main St. bridge. I was born and raised in Piqua and I got to know Mr. Gentile . I shined his shoes every Saturday morning.

That seems to be debated quite often. Several years ago I wanted to clear that up and asked Don’s sister Edith to tell me the story. She was 90 at the time but still working as a volunteer at a hospital. She told me it was the Shawnee Bridge and that he flew in from the south. She said very sternly “and I know he did it because I saw him with my own eyes”. I asked her about the train bridge just beyond and she said he went right under that as well. The N Main bridge makes more sense though. However, my late great uncle, Walter “Irish” Gerard witnessed the early morning bridge flight and said it was the Shawnee bridge as well.

i didnt know i died in a plain crash

HI Dominic, I just finished reading “1000 Destroyed” by Hall, Great read on your dad as well as the group of pilots he associated with .

Any chance of you signing the book? I came across it in a used book store up here in St Paul,,, would have tried to get Len Morgan to sign but he left us back in 2005 i think.

Thanks….carl

I would like to know how Gentile pronounce his name. My Dad was a B-17 Squadron Commander, 708th Bomb Squadron, 407th Bomb Group (H) from about February ’44 through September ’44. He knew very well of Don Gentile’s accomplishments. He pronounce his name “Gentle” like politely/nice/Gentleman. I never asked (of course – duh) but I always thought that was not the correct pronunciation but rather, might have been sort of a name you would use for someone as a friend (he wasn’t a friend. Just knew of his accomplishments.)or as a nickname that was a take off of the correct pronunciation.

I always thought it might be “Gen-teel” or “Gen-til-e’ (long “e”).

I would also like to know the story behind and the meaning of his beautiful “nose art”.

I believe it was his wingman, John Godfrey, who wrote “Tumult in the Clouds”, an excellent book. Godfrey was special in his own way. It seems like he had an artistic, thoughtful side to him. Any comments about that?

It is pronounced Gentilly. I used to say Genteel and my mother would correct me. My great-uncle was Don’s wingman, Johnny Godfrey. He wrote “The look of Eagles”. Tumult in the Clouds was about the whole 4th Fighter Group.

My mother was born in 24′ and was from Greenville. I was told they dated

I thank you for sharing this with us.A simple mistake caused this crash.

Enjoyed the writing and history…I know one of his sons….another fine pilot.