After the downfall of France in WWII, the German Luftwaffe controlled the skies over Europe. Their next objective was to sweep the Royal Air Force from the blues as an essential prerequisite to Hitler’s invasion plans. The British government and military were painfully aware their precious resource of pilots was in limited supply and immediately expanded flight training. But a serious problem arose: With a limited landmass, Jolly Old England could not protect their airfields from marauding German aircraft.

The fighter planes, the Spitfire and Hurricane, were more than a match for the German Messerschmitt Bf-109 and the Focke-Wulf Bf-190. British aviation, although low in aircraft, maintained a priceless edge due to the new-fangled invention called radar, but the British could ill-afford the perilous loss of human resources. The idea occurred to train British pilots in “safe” or “neutral” countries including the “nonaligned” United States of America.

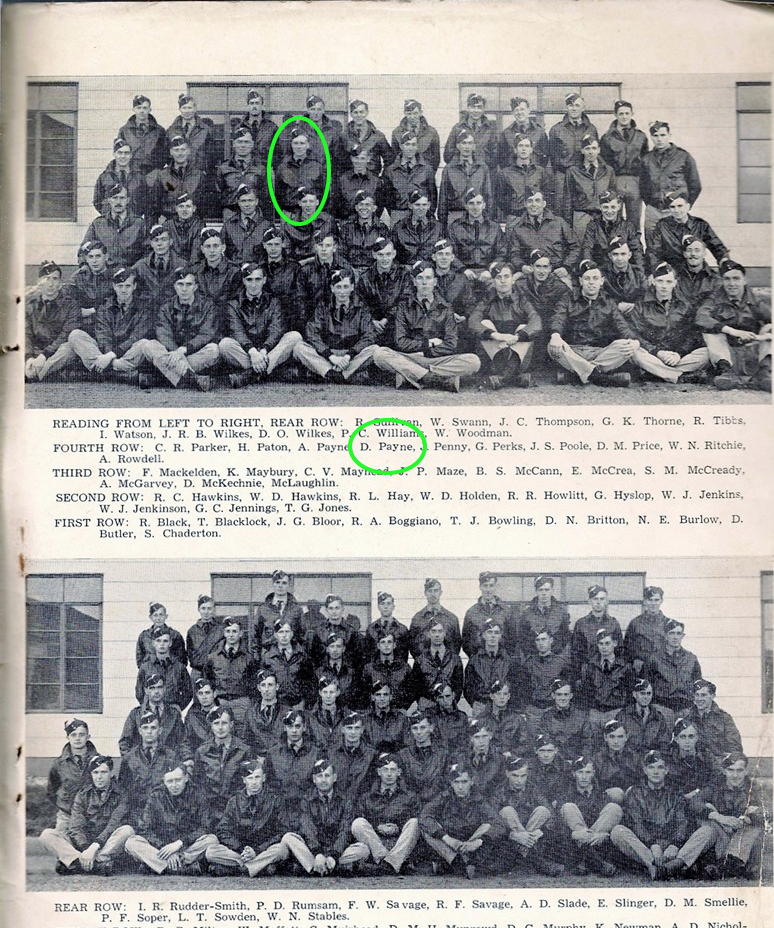

Along comes The Arnold Scheme. Named after its topmost architect, General “Hap” Arnold, the U.S. Army Air Corps instructed British pilots at airfields within the Southeast Air Corps Training Center. The towns and airfield locations included Camden, S.C., Tuscaloosa, Ala., Arcadia and Lakeland, Fla., Americus and Albany, Ga. At these so-called “secret” airfields, over 18,000 British airmen earned their wings. Denis Payne was one of those aviators. Born on Sept. 11, 1919, near Devonport, England, Payne graduated at age 15 from the Colchester High School for Young Gentlemen, then entered the Royal Air Force School to study engineering. At the age of 19 he was flying aboard the obsolete Fairey Battles as a flight engineer. Venerable and slow, the Fairey Battle was easy prey for German fighters.

“I realized to hopefully survive the war I needed to get out of the backseat into a pilot’s seat,” Payne said. He applied for fighter training, was accepted, but before his orders came through Payne fought in the Battle of Britain as a crew member on a Bristol Beaufighter. “The Beaufighter was used for night fighting,” he said. “I remember the missions, all the bullet holes in our plane, a bit scary, it was.”

In late summer 1941, he received orders for fighter training in America. Sent to Montgomery, Ala., Payne recalled, “We spent two weeks adjusting to the weather and trying to understand the Southern language. You may remember that Winston Churchill claimed, ‘England and America are two countries divided by a common language.’ All I can say is, the chap knew what he was talking about.” The summer heat of Montgomery was bad enough, but the British pilots really had problems adjusting to an apparently vulgar system known as West Point military inflexibility. Payne declared, “Bloody hell. We got up at 5 a.m. and hustled everywhere. They told us when to eat; they screamed at us …. we were not very happy blokes!” Next stop: “Secret” training in Americus, Ga., at Souther Field, renamed Jimmy Carter Regional Airport in 2009.

British pilots were not allowed to wear their uniforms into town because of American “neutrality” at the time. Payne stated, “Every man, woman and child in Americus knew we were British subjects, but they treated us magnificently. They invited us to a ‘weenie roast’ during our first week. We’d never eaten hot dogs nor understood the nickname. We were very concerned about what the blokes wanted to roast.”Payne fell in love with America and its people. “We were born into a rigid class system in England, but in Americus we were treated as equals. The townspeople were easy-going and approachable, a big difference from the system I grew up in.”

On Southern cooking: “I loved Southern cooking then and I love it now. We ate fried chicken for the first time; could get peaches, corn on the cob, black-eyed peas, butter beans and cornbread. I visited the local drug store and sat down at what they called the lunch counter. I ordered this thing called a banana split. When that treat was placed in front of me I thought I’d died and gone to heaven.” When asked about fried okra, Payne said, “Listen, mate, I’m only 94 years old; give me a bit more time.” And Southern iced tea? “Now that’s a problematic bit of Southern culture. It’s bad enough that Southerners drop ice cubes in their tea glasses, then add sugar to sweeten it. After that they add lemons to make it tart again. It doesn’t make any bloody sense.” And American beer? Payne replied, “Well, put it this way, we walked into a store in Americus to hopefully purchase a few beers. We got bottles of root beer. Not exactly what we had in mind. We figured the Yanks were hard up for alcohol.” Another incident: “I was in town with my mates and ran into the mayor’s wife. A very nice lady; always had the time to talk with us. When I asked what she was doing in town, she replied, ‘Oh, just piddling around.’ We were speechless. If a British pilot is “piddling” around it’s because he’s had one too many at the local pub. I was sort of worried about the mayor’s wife after that conversation.”

Payne met an American beauty from Manchester, Tenn., named Mary who was working in Americus during the war. Sparks flew, and cupid proved to be an expert archer. They tied the knot within six weeks. The couple has been fighting the language barrier for over 75 years. Payne recalled, “When we first started dating I told Mary to meet me in front of Gaham’s the next weekend. She had no idea what I was talking about. I told her it was the biggest building in town with the name plainly painted on the front in sizable letters. Well, the building was advertising Georgia hams, the lettering was GA HAMS.”

Mary Payne automatically became a British subject by marriage. Once in England she was scheduled for employment with the British military, but an American general recruited Mary due to her dictation skills. She said with a smile, “My talent on the piano helped, too.” Mary had entertained American servicemen with her musical aptitude en route to England via a 60-ship convoy. When Payne met Mary’s parents the first time he asked her father while at the dinner table, “Sir, with your permission, I’d like to knock up your daughter in the morning.” Mary recalled, “Good Lord, dad almost stroked out; his face turned fire engine red.” In British terminology, “knocking someone up in the morning” meant knocking on their bedroom door and serving them breakfast in bed. For the British, the request is a tactful and polite gesture. But Payne said, “Bloody hell, the American fathers could be quite unsettled by the offer.”

Payne’s piloting proficiency earned him a posting teaching navigation in Macon. One responsibility required correcting map and plotting errors made by new recruits. Payne used a large red eraser to correct the penciled-in mistakes. “Well, I corrected so many mistakes I needed a new rubber,” he recalled. “That’s what Brits call an eraser. I went downtown to a Woolworth’s Store and informed an attractive female employee that I needed a big red rubber. She stuttered incomprehensibly for a sec, then directed me across the street to the Rexall Drugstore. I didn’t understand why, but being polite I did as the young lady requested. I approached a female worker in the drugstore and dutifully asked her for a big red rubber. Her face flushed. I wondered what the bloody hell I was doing wrong. Well, she excused herself and fetched the manager. He was a nice lad, but I had to repeat my request. He finally said, ‘Very well, sir, would you like a dozen?’ I said, ‘Good Lord, man, I only need one!’ He replied, ‘Yes, sir’, and walked behind the counter. He opened a drawer and pulled out a handful of Trojans, in all sizes. I realized my blooper, but was too embarrassed to say a word, so I just bought one, a big one. Then I walked immediately back to the British barracks, opened the package and took the thing out and pinned it to the bulletin board with a large note that read: Warning: This is what the bloody Yanks call a rubber!”

Payne’s dedication and aviation abilities earned him an instructor’s slot, receiving the same patriotic pitch from his superiors three times during WWII, “Good instructors are more important than pilots.” Ports-of-calls included instructing aviation cadets in Macon and at the twin-engine fighter school in Scotland. Later assigned to British Bomber Command, Payne trained British pilots on the safe landing techniques of Lancaster, Ventura and Wellington bombers during inclement weather. A natural pilot, his wisdom earned him status as an Aviator-of-all-trades.

On D-Day, June 6, 1944, the Allies launched the Normandy Invasion to liberate Europe. Payne recalled that morning: “We were taking off in a Wellington bomber and, per procedure, pulled up the undercarriage. We never knew the cause but for some reason the bomber continued on down the runway. She pancaked, skidded down the runway and across the motorway then smacked nose-first into a haystack. A brand new bomber, she was, with highly classified radar and other sensitive equipment, totally destroyed.”

Later that afternoon Payne and other aviators were celebrating D-Day in the officer’s mess. “Well, we downed a pint too much,” he stated. “We started passing around a new but very sterile pristine chamber pot filled to the brim with ale. I may say that compelled several blokes to leave the bar. Later we staggered outside, physically picked up an MG sports car then set it down on the dance floor inside the bar. I really can’t tell you what happened after that because we left before the owner showed up.”

After VE-Day, Denis and Mary Payne paid a visit to her hometown in Manchester, Tenn. He recalled, “Mary had not been home in three years and was anxious to see her family. I was happy for her, but never thought I’d be arrested for running corn liquor!” Mary’s friends packed Payne’s car with corn liquor as a prank; called their buddies at the local police department, and they arrested Payne. “It was pretty funny; after it was over,” said Payne. “I still have the distinction as the only British subject thrown into jail for running corn liquor in Manchester, Tenn.”

Denis and Mary Payne’s charming sense of humor conceal their graphic experiences of WWII. They witnessed death and destruction on a daily basis, lost several friends, and knew that the grim reaper could make the fatal call at any given moment. Nevertheless, they fought and lived and loved through the inferno of a World War. The conflict is long over, but the Paynes continued living, loving, and laughing.

After the war Payne found employment at the British Consulate in Atlanta, until his retirement. “That’s right, mate,” he said proudly. “I am the original James Bond, 007. And if you care to believe that, I’ll knock you up with a cup of tea.”

Gentleman Denis Payne passed gently into the good night on June 11, 2013.

Article by Peter Macca via rockdalecitizen.com

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran. For story consideration or comments: [email protected]

To read Pete’s stories visit www.aveteransstory.us

Related Articles

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.